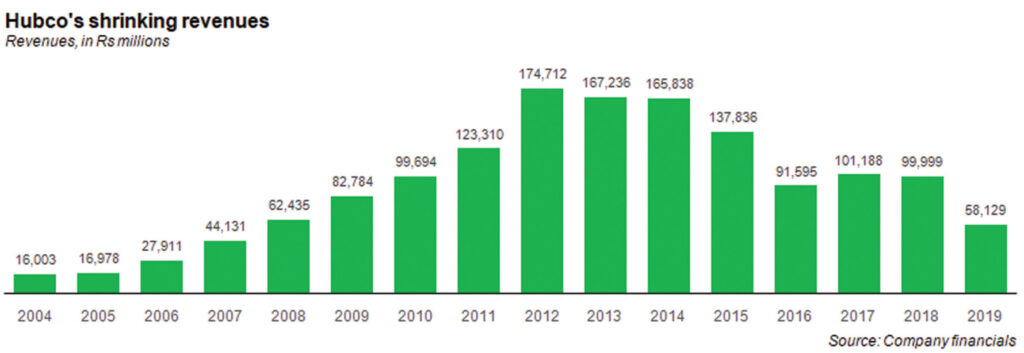

It is not every day one can characterize a company that made Rs11.9 billion in profits last year as struggling, but there is no denying it: Hub Power Company (Hubco), Pakistan’s largest independent power producer (IPP), is in big trouble.

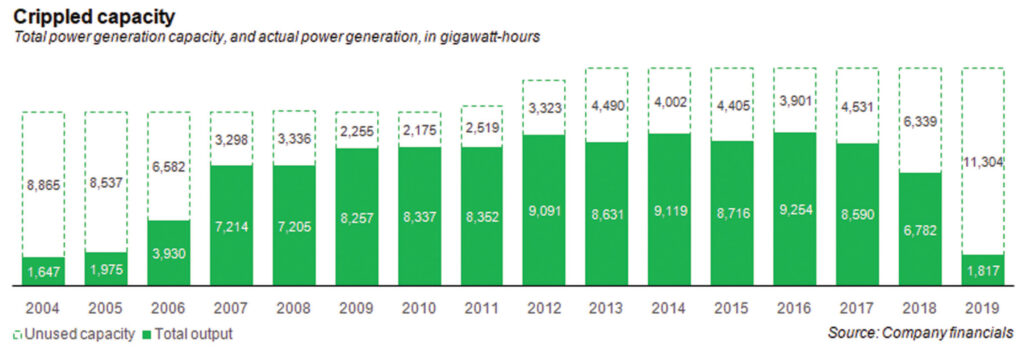

Its base plant – which accounts for just over 80% of its power generation capacity – is effectively shut down, with a load factor of less than 1.3% in the third quarter of calendar year 2019, the most recent for which data is available. Load factor for a power plant refers to the proportion of a plant’s maximum power generation capacity that was actually utilised in a given period.

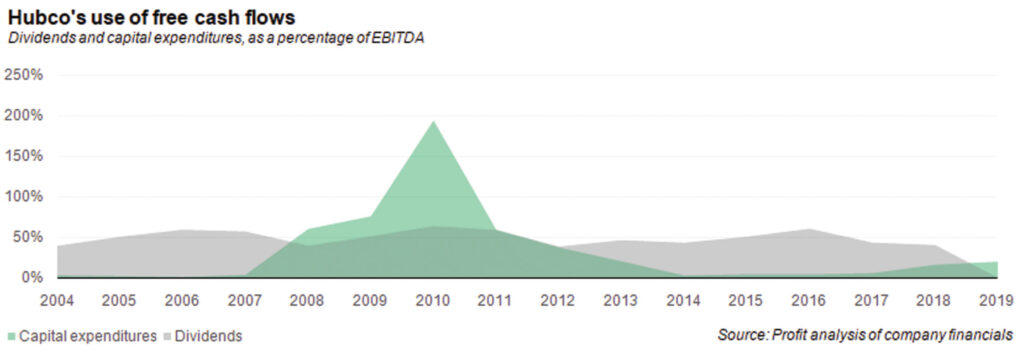

Revenue declined by a staggering 41.9% during the financial year ending June 30, 2019. And while net income for the company is relatively stable, the year 2019 was the first time since 2000 that Hubco did not pay out a dividend.

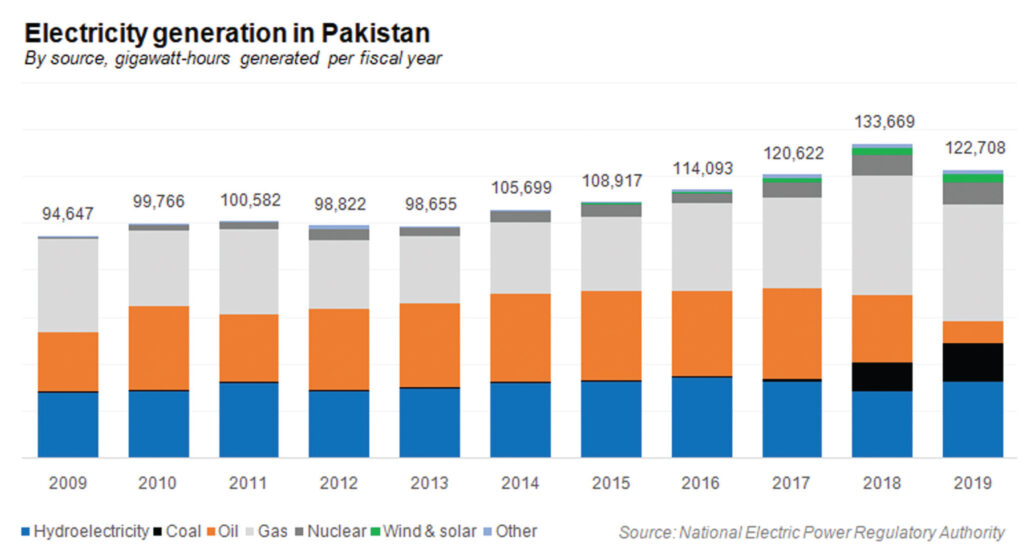

To make matters worse, things are bad for Hubco even as the broader power generation sector continues to recover from the 2018-19 recession. During the third quarter of calendar 2019, power generation across Pakistan increased by 3.9% compared to the same period last year, according to data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). But power generation at Hubco’s main plant declined by more than 90% during that same period.

This is clearly a period of significant pain for Hubco. So why is the company doing so badly in a sector in which it has historically been a dominant player? And what is the management’s plan to fix the problem?

The problem for Hubco is the same it has always been: the company has consistently chosen the wrong fuel for power generation, and not used its good years to plan for much needed overhauls. And it has a habit of foolishly believing the government of Pakistan’s most outlandish promises, taking into consideration the letter of the law without regard for the political sustainability of that which the government has promised the company.

The first among IPPs

The Hub Power Company was the very first independent power company set up in Pakistan, first incorporating in 1991, a few years before the World Bank-backed IPP policy was established in the country in 1994. The bank had been pushing the government of Pakistan since 1985 to establish an IPP policy – allowing independent power generation companies to sell electricity to the national grid – rather than relying on the state-owned electric utility companies to continue expanding their power generation capacity.

The problem for Hub, however, was that it chose oil, among the most volatile of commodities in terms of price, and one for which Pakistan has almost always relied on imported supplies for the bulk of its consumption rather than domestic production. As a result, the price the government-owned power transmission and distribution companies had to pay to buy electricity from Hubco fluctuated wildly, something that the government previously had no experience in.

The main plant – a 1,292-megawatt (MW) furnace oil-fired power plant located in Hub, Balochistan – began operations in March 1997, and almost immediately ran into problems with the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA), which at the time was still responsible for the nation’s energy infrastructure.

Part of the problem was timing: March 1997 was just one month after then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had taken office for the second time, following the dismissal of the second Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP)-led government of Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, on allegations of corruption. Even though the IPP policy was a World Bank initiative that was first contemplated under the Zia Administration, it was easy for the second Nawaz Administration to portray the policy as being overly favourable to power companies at the expense of the government and electricity consumers.

Payments to Hubco from WAPDA were frequently delayed and disputed, even though the government had signed agreements with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) to prevent precisely that sort of thing from happening.

Indeed, Hubco was the first IPP that the World Bank – through the IFC – ever invested in anywhere in the world as a debt and equity investor. The purpose was to give the other local and foreign investors security: a refusal by the state-owned utility companies to pay for the power generated by Hubco would constitute a default on the government of Pakistan’s sovereign debts to the World Bank itself.

But since when has the government of Pakistan ever let a commitment to international organisations and investors ever stop it from refusing to pay its bills?

And then there was the problem of the guaranteed rates of return, which were written into the contracts for Hubco. Presented in an uncharitable manner, it can certainly look like a giveaway to the foreign investor-backed companies, even though there was a good reason for the contracts to be designed the way they were (and continue to be).

The structure of IPP contracts

For much of the history of the human consumption of electricity as a form of energy, the company that delivers electricity to your home is also the company that generated it in a power plant in some industrial part of the city and maintained the power transmission lines that brought it over from that industrial area to the city, and the distribution lines that then spread it to every home and business in the city.

But in developed economies – particularly the United States – there began a trend in the 1970s to try to diversify energy sources. In 1978, the United States Congress passed the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) as a response to the 1973 energy crisis, which created the regulatory mechanism to allow IPPs as a means of making the US energy grid more responsive to supply and demand.

The problem that PURPA was trying to solve was this: electric utilities that set up their own power plants want to have as much of them utilised as possible. That makes those plants good for the base load, which is the minimum level of electricity needed at all times by all homes, businesses, and industrial units throughout the grid.

However, utilities have very little incentive to set up their own power plants to handle peak loads, which happen both seasonally (summer generally requires more electricity due to air-conditioning needs) and each day (daytime energy consumption is generally higher than nighttime).

The energy crisis of 1973 exposed that problem of incentives, and energy shortages prompted the US government to seek a solution where the utilities’ own power generation capacity could be supplemented by independent power generation companies that could sell electricity to the utilities.

As with many economic mechanisms around the world, the US model then served as a template for energy projects around the world, and Hubco in Pakistan was the very first time an IPP was set up in a developing country. In order to understand how Hubco gets paid, therefore, it helps to understand the change that PURPA brought about, and that the 1994 (and subsequent) IPP policies in Pakistan have tried to replicate.

The biggest problem with electric utilities is that they are natural monopolies: in any given city or metropolitan area, it is impossible to have more than one utility. You cannot have more than one company build a set of electricity lines that come to your house; it would just be too expensive to do so.

That means that governments heavily regulate electricity prices to consumers to prevent companies from abusing their natural monopoly power. The creation of IPPs, however, created a second constituency that would be subject to the threat of the natural monopoly power of utility companies, albeit this time it would be another set of companies.

Nonetheless, any investor setting up an IPP has a problem: in most places in the world, there is only one company – usually government-owned – that can buy the electricity that they produce. And while they can come up with rules and contracts that govern that relationship, at the end of the day, if there is only one buyer for my product, I need some guarantees that they will actually buy the product.

This is why IPP contracts are constructed on a “take or pay” basis: the electric utility – in Pakistan’s case, WAPDA, and now the Central Power Purchasing Authority (CPPA) – either has to buy the power generated by the IPP, or else pay them some amount that would compensate for at least the cost of the infrastructure that the IPP set up to generate electricity.

Power tariffs paid to IPPs – which are different from the tariffs that ordinary consumers pay to utility companies – therefore have two components: power charges and capacity charges.

The first of these is the simplest to explain: the state-owned utility companies pay the IPP a rate for each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity they buy from it, which includes the cost of fuel as well as a fixed profit margin for the IPP that would cover the full cost of the capital it took to set up its infrastructure. If the IPP is operating at a high enough capacity, this rate would be the only thing that the utility needs to pay the IPP.

The second component of the IPP’s tariffs are called capacity charges: if the IPP’s power plant is available for production, but the utility company either does not need to or decides not to buy the electricity from the IPP, then the utility company needs to pay the IPP a “capacity charge” to pay for the cost of setting up the infrastructure and keeping it available for the utility.

This is the “or pay” part of “take or pay”.

Built into both of these components is a fixed profit margin for the IPP, which can be set as either a fixed return on equity (ROE) or fixed internal rate of return (IRR), two different measures of profitability. In the case of Pakistan’s IPP policy, which is meant to be attractive to both domestic and foreign investors, the fixed profit margin is set in US dollars, and adjusted every year for US-dollar-denominated inflation (as measured by the consumer price index in the United States).

Under the IPP policy of 1994, Hubco was entitled to receive an IRR of 17% in US dollar terms, and adjusted for US inflation. This number can certainly sound like quite a lot, especially when one considers the fact that IPPs in the US receive a 10% IRR, which is not always adjusted for inflation. Nonetheless, investing in Pakistan is considerably riskier than investing in the United States, and hence a higher IRR was needed by the government to be able to attract investors into the country’s power sector.

And this number is somewhat misleading: a 17% IRR does not mean than the government is allowing a 17% profit margin on each unit of electricity. When a plant is operating at above 60% capacity, the profit margin for the company is usually no more than 4-6% of total revenues.

In other words, a 17% IRR does not mean that if the government is buying electricity at Rs10 per unit, that the IPP is making Rs1.7 per unit in profits. When the system is working well, it means that the IPP is making anywhere between Rs0.40 and Rs0.60 in profits.

But of course, as you can see, it is easy to portray this as an excessive giveaway to the IPPs at the expense of ordinary consumers, which is exactly what the Nawaz Administration did during their second tenure in office.

The dispute and WAPDA deal

The Nawaz Administration balked at having to pay Hubco the rates that had been negotiated under the 30-year Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between WAPDA and Hubco, which was signed in early 1997. As a result, the government frequently came close to defaulting on its obligations to the company (technically, it did, but Hubco and the World Bank were in negotiations with the government and therefore, never formally triggered the default clauses.)

The dispute lasted for five years during which time Hubco almost never got paid on time. It was not until the Musharraf Administration took office – and began reviewing the previous government’s activities – that the dispute was eventually resolved, though it took three years even under that supposedly business-friendly administration.

In 2002, the government signed a revised agreement with Hubco, which reduced the IRR Hubco was entitled to from 17% to 12%. Even President Musharraf and Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz, it seemed, were persuaded that the profit margin was too high.

The Zardari-Nawaz heyday

Under the Musharraf Administration, Hubco was used mostly as a peaker: the power plants that are used to manage peak loads of electricity for the national grid, and not part of the base load, the power plants that are running all the time because they provide the electricity that is being used all the time.

It was in 2008, towards the end of the Musharraf era and the beginning of the PPP-led Zardari Administration, that the status of Hubco changed.

September 2007 was when oil prices reached $100 a barrel for the first time since the early 1980s. Oil prices rose through all of 2007 and through the first half of 2008. This made oil-fired electricity extremely expensive, and one would think that this would be bad for the nation’s largest oil-fired power plant. Fortunately for Hubco, there were two things happening at that time that would end up working heavily in the company’s favour.

The first of these was the fact that Pakistan was beginning to run low on natural gas after the Musharraf Administration’s bonanza of giving away natural gas to any constituency that asked for it without regard to the full economic cost of extracting the gas and without regard for the fact that the country has finite reserves where the biggest fields were already nearing depletion even when their administration came into office.

That meant that the gas-fired power plants owned by the government itself were unable to function on natural gas in the manner that they have been able to over the past decade, particularly since the Musharraf Administration had promised a higher priority to natural gas consumption to the captive power plants owned by export-oriented textile mills, as feedstock for fertiliser manufacturers, and even to compressed natural gas (CNG) fuel stations for vehicles.

The government’s power plants have the ability to run on either furnace oil or natural gas, so when they could not run on natural gas, one would think that they could simply be converted to running on furnace oil. The electricity generated would be expensive, but at least the government would not have to shut down its power plants.

Unfortunately for the new administration, they were about to find out just how little the Musharraf Administration had invested in the nation’ energy infrastructure. The government’s power plants produced reasonably priced electricity on natural gas because natural gas has historically been an absurdly cheap fuel. When forced to operate on oil, especially expensive oil, the inefficiency of those power plants became abundantly clear. The government simply could not operate those plants without having to offer absurdly heavy subsidies on the electricity it would then sell to consumers.

And so, in came the IPPs, led by Hubco. The base load of the country’s electricity grid between the years 2007 and 2018 was handled effectively by the hydroelectric power plants at the massive dams at Tarbela and Mangla, and by the oil-fired power plants owned and operated by the IPPs. The IPPs were also using expensive furnace oil, but at least they were using it more efficiently – in some cases, up to three times more efficiently – than the government’s own power plants.

(You might ask: why did the government just not invest in fixing its own power plants? Dear reader, why do you ask such silly questions? Really? The government of Pakistan, act in a rational manner? Seriously, where have you been?)

So, what went wrong?

Well, for starters, not much was right to begin with. There is no reason why IPPs cannot be used as the base load, but using oil-fired power plants to serve as the base load while giving away cheap gas to minuscule – and less efficient – power plants owned by the textile mills was a gross misallocation of resources.

It worked for 10 years because the government has continued to pump in money into the system in the form of formal electricity subsidies at unsustainably high levels and then three “one-off” injections of capital into the energy system as a means of clearing the intercorporate “circular debt” that piled up because the government could not actually afford the energy being produced and did not want to force consumers to pay for it.

What went wrong with the energy grid and why will be the subject of a future feature story in Profit, but suffice it to say that the 12-hour rolling blackouts in major cities (and near-complete lack of electricity in the rural areas) should have been a hint that something major was wrong.

So when the Nawaz Administration came into office in 2013 for the third time, items one, two, and three on their agenda were to fix the electricity grid in the country.

The prime minister’s plan was simple: if the problem was that there was not enough electricity and the electricity that was being produced was too expensive, then the way to solve both problems at the same time would be to add lots of additional power generation capacity that used a much cheaper fuel. And given the electoral constraints of their five-year term in office, the PM wanted it all done fast.

The strategy the government chose was this: incentivise – using promises of stupidly high fixed profit margins (around 27% ROE) – the production of electricity using coal-fired power plants. Coal is among the cheapest fuels in the world, and so coal-fired power would bring down the weighted average cost of producing electricity. And if lots of such plants were built fast, the weighted average cost would come down faster.

The upside was that the strategy worked: In the five years that the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) was in office, Pakistan’s power generation capacity jumped by 50%, from 24,000 megawatts to 36,000 megawatts. Nearly all of that addition was coal-fired power plants.

The downside, of course, is that almost all of Punjab cannot breathe for two months a year partly due to the smoke that is caused by the massive coal-burning power plants that have been set up all over the province and elsewhere.

One of the changes that the government implemented as part of its strategy to bring down the weighted average cost was to ensure that the cheapest fuels were used first in the order of priority for which electricity the state-owned utility companies would buy. That meant that furnace oil-fired power plants – like Hubco’s main plant – were no longer the desired plants, and went from being base load to barely even being peakers anymore.

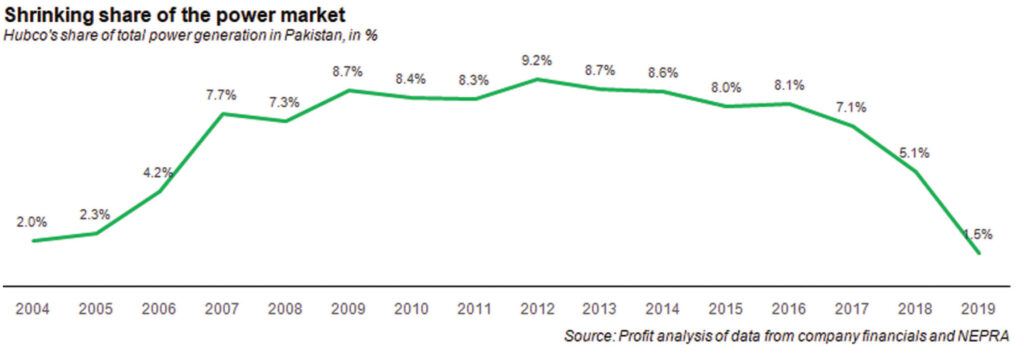

Oil went from accounting for 36.3% of all electricity produced in Pakistan in fiscal year 2013 to just 7.4% in fiscal 2019. Along with that shift in fuel came a decline in Hubco’s fortunes.

How to turn it around

As a result, Hubco went from receiving nearly all of its revenues from tariffs received for electricity produced to having nearly half of its annual revenues coming from capacity charges, with its main plant sitting effectively completely idle for most of the year now.

The company’s management is well aware of the fact that while capacity payments are something they are entitled to legally, they cannot rely on capacity payments as a sustainable business model.

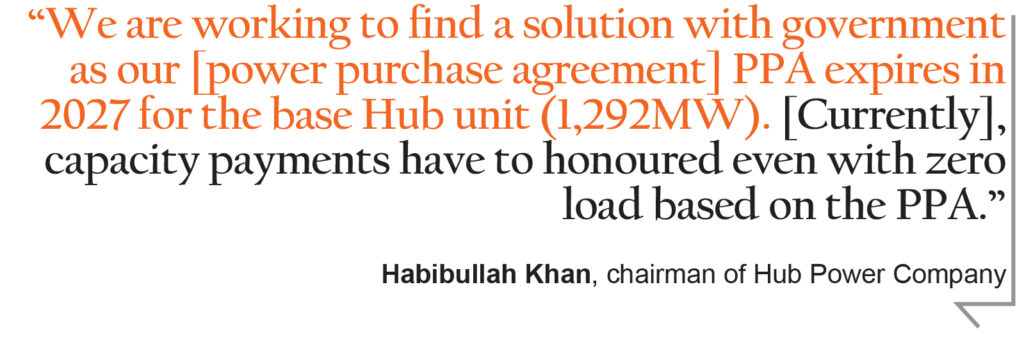

“We are working to find a solution with government as our [power purchase agreement] PPA expires in 2027 for the base Hub unit (1,292MW),” said Habibullah Khan, chairman and largest shareholder of Hubco, in a statement to Profit. “[Currently], capacity payments have to be honoured even with zero load based on the PPA.”

It is clear, however, that the company’s ownership at least recognises that just because the company is entitled to something does not mean that it should not try to ease the government’s burden to the extent possible.

“To ease the circular debt strain on the government we have offered two options,” said the chairman. “The first one is to convert two units (300 MW each) into coal power units through a conversion process. Alternatively, we can also convert all four units at Hub to coal and supply K-Electric, with which we have already signed a memorandum of understanding, subject to government approval of our terms.”

Why convert just two units to coal-fired power when converting all four is an option and would yield cheaper electricity? Because the first option would leave open other possibilities, including Hubco converting from being just a power company to becoming a company that is both in the electricity and water business.

“We would further consider the other two units to convert for a desalination water plant, working with both the federal and provincial governments, to mitigate the current water shortage in Karachi, which is currently 600 million gallons per day,” said Habibullah Khan, adding that the company was still undertaking analysis to determine whether such a desalination business would be financially viable and cost-effective.

The company’s water initiative – if successful – would be able to supply up to 50 million gallons per day of that shortfall. In addition, Hubco is exploring a separate agreement to supply 5 million gallons per day of water to the Defence Housing Authority (DHA), the military-owned suburb, in Karachi.

Hubco has also offered to upgrade the transmission infrastructure to allow it to start selling electricity directly to K-Electric rather than selling to the state-owned National Transmission and Dispatch Company (NTDC) first, and then having K-Electric buy that electricity from NTDC.

But the main strategy for the company is to invest heavily in coal-fired power plants.

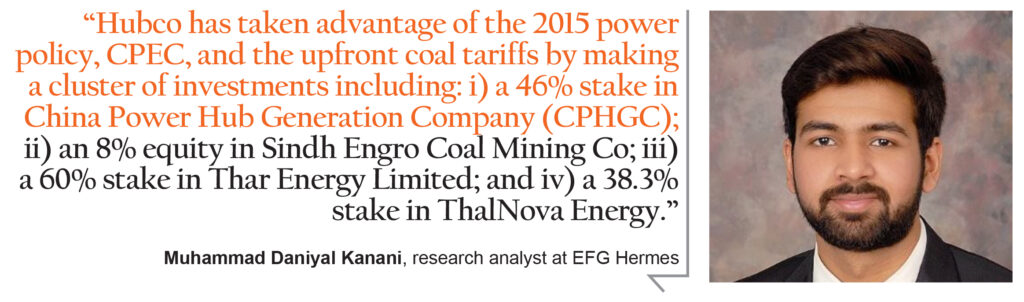

“Hubco has taken advantage of the 2015 power policy, CPEC, and the upfront coal tariffs by making a cluster of investments including: i) a 46% stake in China Power Hub Generation Company (CPHGC); ii) an 8% equity in Sindh Engro Coal Mining Co; iii) a 60% stake in Thar Energy Limited; and iv) a 38.3% stake in ThalNova Energy,” wrote Muhammad Daniyal Kanani, a research analyst at EFG Hermes, an investment bank, in a detailed research report issued to clients on August 20.

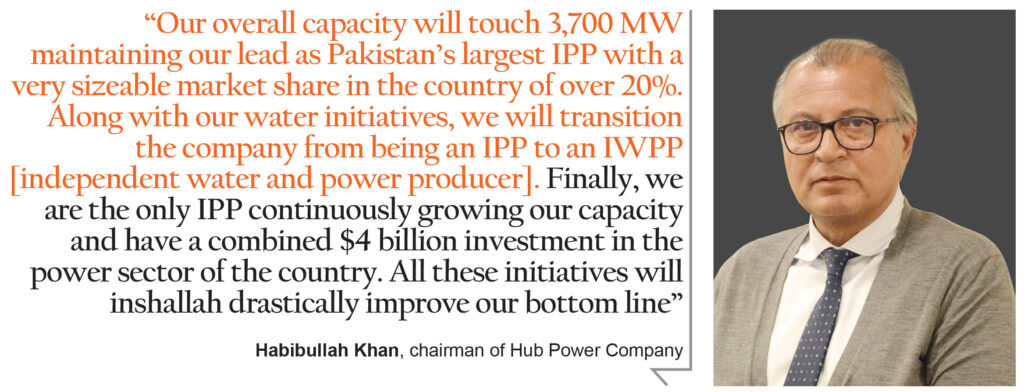

“Based on this, our overall capacity will touch 3,700 MW maintaining our lead as Pakistan’s largest IPP with a very sizeable market share in the country of over 20%,” said Habibullah Khan. “Along with our water initiatives, we will transition the company from being an IPP to an IWPP [independent water and power producer].”

“Finally, we are the only IPP continuously growing our capacity and have a combined $4 billion investment in the power sector of the country,” said the chairman. “All these initiatives will inshallah drastically improve our bottom line.”

The problem with coal is that while it solves the problem Pakistan was facing five to ten years ago, it has now become a problem in its own right, with its environmental impact, and increasing political scrutiny of those higher rates of return are likely to create pressure on the company’s revenues and cash flows in future years.

The Hubco management clearly understand that their business – dependent as it is on the government – requires them to be more sensitive to political calculations more than most others. However, in jumping headlong into coal, the company may end up just replacing one set of political problems with another.

Perhaps that explains why Habibullah Khan – the reclusive billionaire who owns the largest shares in both Hubco and K-Electric, the nation’s only privately-owned electric utility company – wants to do deals between Hubco and K-Electric instead of between Hubco and the government. A Hubco agreement to sell electricity directly to K-Electric would cut the government out of the loop as a buyer, and reduce its role to that of just a regulator. In an ideal world, this would solve at least part of the company’s problem.

But would it be enough? We will know in about a decade from now.

It’s nice effort but kind of misleading. Only one large coal project setup in Punjab that is Sahiwal coal plant.

Agree! Three big power coal power projects are Sahiwal-Pubjab, Port Qasim-Sindh, ChinaHub-Bloch, others are small projects located in Thar, Sindh. The current environment problem in Punjab is from India.

Second, 27% IRRs is wrong. 27% is ROE, not IRR. If compare, 27% ROS is around 16% IRR.

The largest IPP is KAPCO

Baseless & factless. The guy is not much familiar with whats happening with the power sector or just wants to force his opinion through fact fudging.

Another feather in Hub Power Plant’s cap other than the first IPP of Pakistan is that plant being 22 Years old is still perfectly and reliably capable to demonstrate 100% availability through ADC (Annual Dependable Capacity Test). ADC is witnessed by WAPDA/NEPRA every year. This indicates that the Plant maintenance is kept up to the mark by a very well trained and competent Team.

Although a bit misleading but contains very useful insights for someone who knows the IPPs operation system

Comments are closed.