Amid all of the chaos of the current year, one of the less noticeable moments was the hasty resignation of former Malaysian Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohammed. The nonagenarian statesman was shown out of office after his own party and the opposition had united against him.

The politics of the Southeast Asian country still managed to make waves in Pakistan, however, mostly because of the close personal ties and admiration that incumbent Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has with Mahathir. And Mahathir’s positive disposition towards Pakistan has come in handy in recent years.

Under Mahathir, Malaysia supported Pakistan in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on the Kashmir issue. There was also an attempt to create a non-Arab alliance in the Muslim world between Pakistan, Turkey, and Malaysia.

With all of these positive indicators, the Pakistani government had not just been banking on Malaysia as an ally, but also possibly as a major trade partner. However, the hopes entered choppy waters even before 2020 began.

In December last year, Prime Minister Imran Khan cancelled his trip to Malaysia for an Islamic conference on the insistence of Saudi Arabia. This was followed by Mahathir, with whom Imran Khan had found common ground before, being ousted from the premiership in March. This was also exactly when the first cases of coronavirus began to be reported in both countries, prompting a general slowdown in economic activity.

However, despite this series of unfortunate events, the groundwork for strong Malaysia-Pakistan trade ties has been laid out long before Imran Khan and Mahathir Mohammad. The two countries have in place a Free Trade Agreement signed in 2004.

An Early Harvest Program (EHP) was also signed between the countries in January 2006. After the successful implementation of the EHP, the Malaysia-Pakistan Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (MPCEPA) was signed in November 2007 and came into effect in January 2008.

With the infrastructure still in place, Pakistan and Malaysia could still manage to become major trading partners, something that would greatly benefit Pakistan.

A closer look at MPCEPA

The Malaysia Pakistan Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (MPCEPA) is the first bilateral FTA signed between two Muslim countries who are also members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

It is also Pakistan’s first comprehensive FTA integrating trade in goods and services along with investment and Malaysia’s first bilateral FTA with a South Asian country. Comprehensive FTAs usually refer to trade agreements that include more ambitious liberalization commitments than those defined in WTO agreements.

Hence, the MPCEPA encompasses liberalization in the trade of goods and services, investment, as well as bilateral technical cooperation and capacity building in areas such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures, intellectual property protection, construction, tourism, healthcare and telecommunications, according to the second review of MPCEPA carried out by Rabia Tariq, a lead researcher at Pakistan Business Council and team leader Samir. S Amir.

Why does this more than decade old economic partnership agreement matter now? Because more and more people are looking towards Southeast Asia for economic opportunity, and the main place they look towards is Malaysia. According to Shahid Ghani, a recruitment agent near Ganga Ram hospital, the Guld market is fading, and the future will be in places like Malaysia. “I am getting lots of applications from local skilled workers who have returned from Dubai and they want to try their luck in Malaysia,” he says.

Remittances coming in from Malaysia have indeed risen over the years, with $17 million coming in in October 2020. And with the MPCEPA in place, there are many benefits that could be made use of more than they already are.

Under the agreement, for trade in goods, both countries agreed to progressively reduce or eliminate tariffs on agricultural and industrial products. Pakistan agreed to eliminate tariffs on 43.2% of imports from Malaysia by 2012. During the MPCEPA reviews in 2009 and 2011, Pakistan also agreed to further reduce tariffs by 2014. Hence, Pakistan offered concessions to Malaysia on around 6,803 tariff lines.

Additionally, Pakistan placed five palm-based products – margarine, glycerol, non-ionic soap, medium density fiberboard and other related commodities – under MOP Track I. Being on the MOP Track I means that the import tariff was reduced by 5.0% MOP in January 2008 followed by an additional 5.0% MOP every year till 2011.

MOP Track II includes Crude Palm Oil, Palm stearin, RBD palm oil, Palm olein, Crude Palm Kernel oil and other related commodities. Under this track, import duty was reduced by 10.0% in 2008 followed by an additional 5.0% starting from 2010. In turn, Malaysia agreed to eliminate tariffs on 78.0% of its imports from Pakistan by 2012. Overall, Malaysia offered concessions on around 10,593 tariff lines.

For trade in services, both countries have provided WTO-plus market access to each other. Pakistan has secured 100.0% equity in Malaysia in computer and IT-related services, Islamic banking and Islamic insurance. Mutual recognition arrangements (MRAs), are also covered in the MPCEPA which offer a framework for accreditation of educational institutions and academic programs. To facilitate entrepreneurs of both countries, the FTA also incorporates a chapter on investment which includes incentives available to investors from Pakistan and Malaysia.

What does precedent say?

The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 2004 and economic partnership agreement of 2007 between both countries have come late in their diplomatic ties. Pakistan-Malaysia relations first began in 1957, when Malaysia first gained its independence. However, the relationship got off to a rocky start because of Malaysia’s stance on the 1965 war between India and Pakistan.

While the diplomatic spat was soon resolved with the arbitration of the Shah of Iran, agreements were slow to proceed. Both countries went on to sign an Air agreement in 1973 and a Cultural agreement in 1979, but would not get around to signing their FTA for another two decades. But one way to gauge the possible success of the agreements could be by seeing the success of other similar agreements that Malaysia has signed with other countries.

Malaysia has signed bilateral FTAs with six countries other than Pakistan. These include Australia, Chile, India, Japan, New Zealand and Turkey. Moreover, since ASEAN has established an ASEAN Free

Trade Area (AFTA), Malaysia also has regional FTAs with China, and Korea. Currently the country is involved in four FTA negotiations namely Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), Malaysia-Iran Preferential Trade Agreement (MIPTA), Malaysia-European Free Trade Area Economic Partnership Agreement (MEEPA) and Malaysia-EU Free Trade Agreement (MEUFTA).

Researchers stated that in the case of bilateral trade with Japan, New Zealand, Chile and Turkey, Malaysia’s trade balance has improved since the FTA has been brought into effect. “On the other hand, in the case of bilateral trade with Pakistan, India and Australia, Malaysia’s trade balance has worsened since the year of implementation,” they wrote in the second review.

Further analysis shows that Malaysia’s imports from India have almost doubled since 2011 whereas its exports to the country remained stagnant. This is because Malaysia imports large amounts of mineral oils and aluminum from India. In the case of the trade balance worsening with Australia, it is due to the fact that Malaysia recorded lower commodity sales to major buyers such as Australia, Japan, China and Thailand in 2019.

It is worth noting that Pakistan has been offered 0% duty on the lowest number of tariff lines. Meanwhile, India has been offered 0% tariff on 12,169 tariff lines which is the highest number as compared to other FTA partner countries. As a consequence, Pakistan might not be in a position to compete in the Malaysian market, owing to this discrepancy in provisions offered by Malaysia to Pakistan as compared to other countries.

Bilateral trade

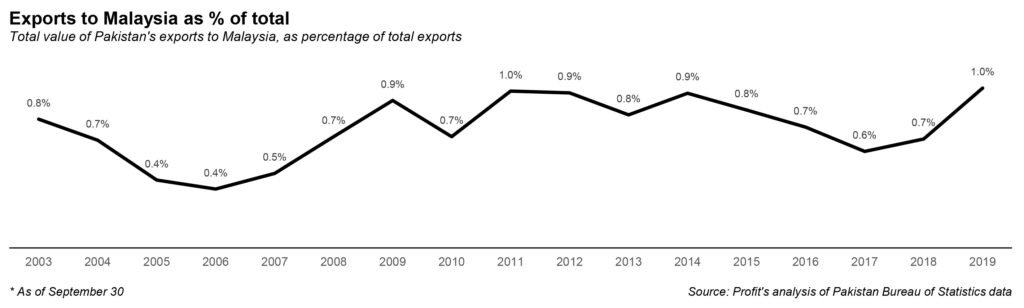

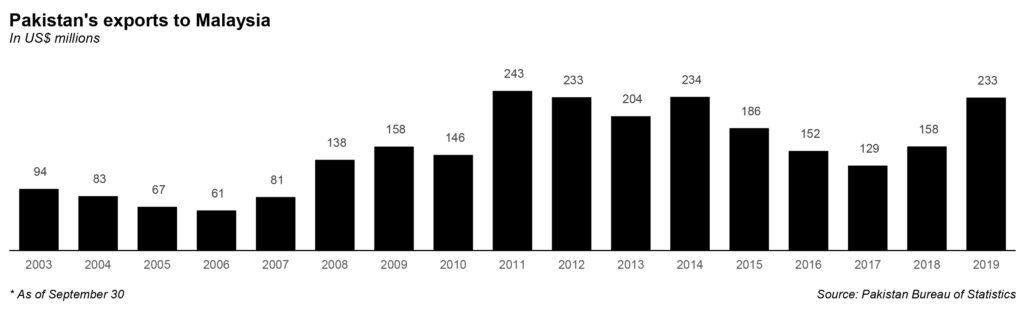

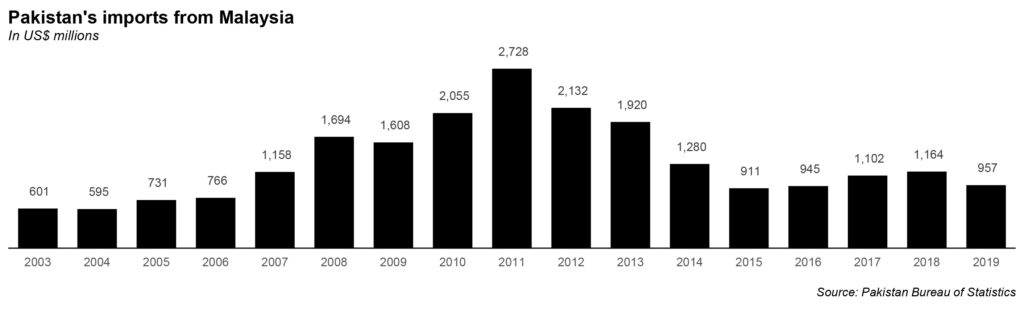

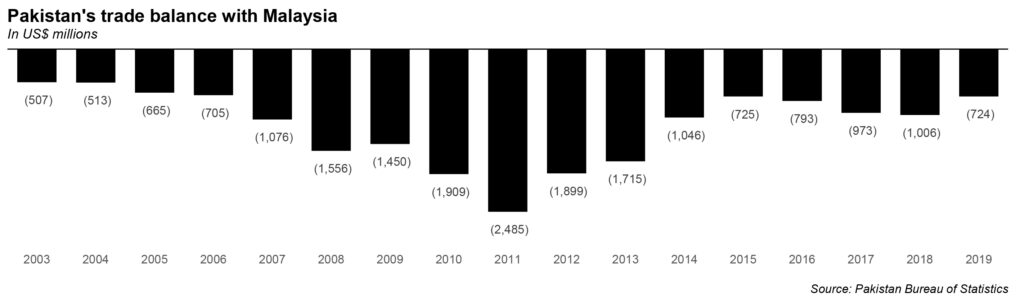

In bilateral trade, the Pakistan-Malaysia numbers have been positive for Pakistan in recent years, but do not reflect the potential of the partnership. Pakistan’s imports from Malaysia decreased from $1.7 billion in 2008 to $956.9 million in 2019, while its exports to Malaysia increased from $138.1 million to $232.8 million during the same period. This led to the lowest ever trade deficit in 2019 of $724.1 million for Pakistan since the implementation of the FTA.

Pakistan’s imports from Malaysia reached a peak in 2011 after which they declined till 2015. This can partly be attributed to the FTA signed with Indonesia in 2013, after which, Pakistan started importing considerable amounts of palm oil from Indonesia. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s exports to Malaysia did not experience significant growth, indicating that Pakistan might not be utilizing the FTA to the fullest.

All in all, the trade balance has been in favor of Malaysia since 2008, and currently, Pakistan’s imports from Malaysia are at least three times more than its exports to that country. Even though the trade deficit has decreased since the implementation of MPCEPA, it appears Pakistan has not been able to become a significant trading partner for Malaysia, despite having an FTA with the country.

Other top imports from Malaysia consist of Machinery, Organic chemicals, Plastics and so on. Combined, the top ten commodities at HS-02 level accounted for 80.2% of Pakistan’s total imports from Malaysia. A more detailed table below shows Pakistan’s top 25 imports from Malaysia at HS-06 level in 2008 and then again in 2019, along with the share of these commodities in Pakistan’s total imports from Malaysia, the

growth rate during this period and the tariff applied by Pakistan on Malaysia.

According to researchers, who carried out the second review of MPCEPA, Pakistan’s imports from Malaysia have fallen annually at a rate of 5.1% since the implementation of MPCEPA. “Combined, the top 25 imports at HS-06 level accounted for 79.1% of Pakistan’s total imports from Malaysia in 2019,” they stated.

With an import value of $231.4 million, “Palm oil and its fractions, whether or not refined (excluding chemically modified and crude)” (HS-151190) is Pakistan’s top import from the country in 2019.

According to the PBC research, this single commodity accounted for 24.2% of Pakistan’s imports from Malaysia. However, the import of this product has fallen at a rate of 11.6% since Pakistan started importing palm oil from Indonesia following its PTA with that country.

Pakistan’s highest export commodity to Malaysia was mineral fuels, mineral oils and products of their distillation; bituminous substances, which amounted to $41.6 million in 2019.

However, in 2008, Pakistan did not export this commodity to Malaysia. Following closely with an export value of $40.0 million. Products exported included cereals, which was the second highest export to Malaysia during 2019, even though the growth rate of this category has not been that significant since the MPCEPA came into effect.

Other top exports include edible vegetables, fish products and textile products such as cotton, textile articles and articles of apparel and clothing accessories. Combined, the top ten exports at HS-02 level to Malaysia accounted for 83.9% of Pakistan’s total exports to Malaysia. Ten out of the top 25 exports consist of agricultural products and food items (HS-01-24). Combined, these products accounted for 39.1% of Pakistan’s exports to Malaysia.

The tariff applied by Malaysia on almost all of these products is 0.0% for all its FTA partners except on denatured ethyl alcohol and other spirits of any strength, broken rice, and semi-milled or wholly milled rice.

In the case of rice, the tariff rate applied is 28.0% and 40.0%, respectively for all FTA partners except India. India enjoys lower tariff rates on rice which is why it is the third largest exporter of semi-milled or wholly milled rice. Pakistan is the fourth largest supplier of this commodity. The top two suppliers are Vietnam and Thailand, both ASEAN members, who also face a lower tariff of 20.0%.

In the case of broken rice, Pakistan is the largest exporter to Malaysia, despite a higher tariff of 28.0% as compared to its competitors Vietnam, Myanmar and Thailand, who face 18.0% tariff. However, since the FTA came into effect, Pakistan’s export of this product to Malaysia has fallen at a rate of 5.3%.

Pakistan’s potential to export to Malaysia

The aggregate export potential for Pakistan’s top 25 products amounted to $2.0 billion in 2019. However, the country only exported goods worth $74.2 million from the top 25 high potential goods to Malaysia during the year.

“Semi-milled or wholly milled rice, whether or not polished or glazed” (HS-100630) holds the highest potential worth $421.9 million. This commodity was also Pakistan’s third-largest export to Malaysia and was classified as a Falling Star in the EPD Matrix,” the second research review of MPCEPA read.

The product with the second-highest potential in 2019 were instruments and appliances used in medical, surgical or veterinary sciences. While Pakistan had the potential to export $404.2 million worth of such products in 2019, it exported a mere $1.3 million to Malaysia. Furthermore, according to the review, “medications consisting of mixed or unmixed products for therapeutic or prophylactic purposes also have high potential as well.

However, Pakistan’s Pharma and Drug regulatory authorities are not registered with the International Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention. Due to this, export of such products to Malaysia remains limited.

The researchers, Rabia Tariq and Samir S. Amir, suggest that with no tariffs applied on these products by Malaysia, Pakistan should try to tap into this potential market by gaining recognition from international authorities since the country already produces high quality pharmaceutical products.

On the textile front, the reason behind Pakistan not meeting its potential is that Pakistani textile exporters prefer markets like the EU and USA due to the EU GSP+ benefit, and due to the fact that textile goods can be sold with a high markup in these destinations.

However, since most textile goods under MPCEPA are also allowed zero duty access, Pakistan should try to tap into this potential market as well. More trade fairs and marketing of textile goods, especially high value-added products in place of raw material (cotton), will allow Pakistan to tap into this market.

What should Pakistan do>

To fully utilize MPCEPA, Pakistan can focus on increasing its exports of fruits, vegetables, rice and meat to Malaysia. Since these products are in high demand in the Malaysian market, focusing on these can boost Pakistan’s exports, ensuring that the country utilizes the concessions provided by Malaysia on such products. An issue in this regard is the lack of direct flights from Pakistan and Malaysia which is necessary for the transportation of perishables. If this issue is resolved, trade under MPCEPA can increase.

Furthermore, Pakistan needs to learn from competitor countries such as the ASEAN members like Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia or other competitors such as India. Participation in trade fairs, along with branding, marketing and packaging of the products according to international standards is vital to increase market share in the Malaysian market, they maintained.