“Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning.” Thus begins Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, one of the most important works of European literature. There are days when the Byco management and shareholders must find themselves relating well with the tribulations of the fictional Joseph K.

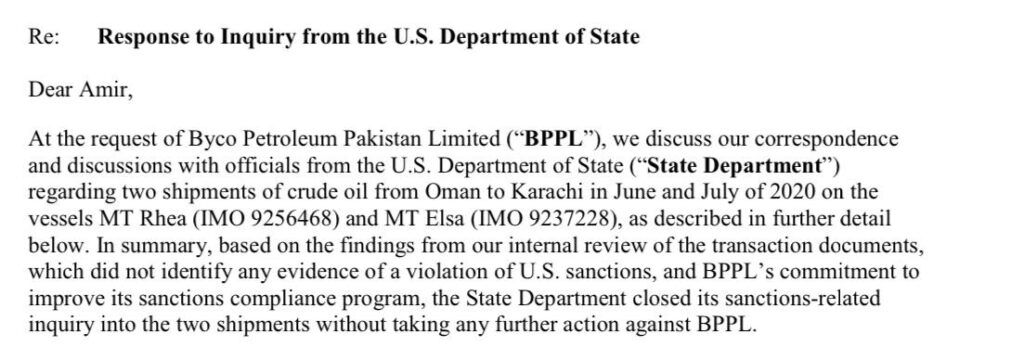

In recent months, Byco has found itself in the news for all the wrong reasons, and it usually stands accused of doing something that it later transpires it had never come even close to doing. Creating an artificial shortage in the Pakistani oil market? Apparently Byco has the power to do that. Violating international sanctions? Accuse Byco. Defrauding state-owned oil companies? Sure, why not? Throw that accusation onto the pile too.

Some of the accusations are just utterly ridiculous, like the one about Byco being responsible for causing the oil shortages in Pakistan in 2020. Byco simply does not have the kind of market share to be able to do that, and data presented in the government’s own inquiries found that Byco’s storage capacity was in fact responsible for helping ameliorate the crisis rather than exacerbating it. Strangely, the government seemed unwilling to state that fact, even though its own numbers said as much.

And other accusations are really because officials at the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) do not seem to understand the concept of receivables and payables on a company’s balance sheet.

This story is not about those accusations or a debunking of them. The above paragraphs are sufficient to address the seriousness of the charges in question. Instead, this story is about why those accusations have been made in the first place, who has the most incentive to make those accusations and why, and what their existence says about the state of play in Pakistan’s energy sector.

It is an examination of a company that is emblematic of Pakistan’s private sector oil and gas companies: trying to serve the country’s energy needs while competing against some of the biggest oil and gas giants in the world, and hamstrung by a regulatory environment that places them in a bad halfway house between market-based pricing and government-controlled pricing.

Why does any of this matter? Because Byco is Pakistan’s largest refinery company and one of its larger oil marketing companies. What happens to this company is reflective of important trends in Pakistan’s oil and gas sector.

Byco’s origins

The story of Byco starts with that of its founder, Parvez Abbasi. Born in 1940, Abbasi attended Government College Lahore, from where he graduated in 1960 and joined Shaw Wallace Pakistan, a shipping and trade finance company that was the local subsidiary of RG Wallace, a UK-based company. He worked there for nine years before moving on to working at Caltex Pakistan, the local subsidiary of what is now the American oil giant Chevron. Abbasi stayed at Caltex for the next ten years.

That experience working in both shipping and oil marketing gave Abbasi the kind of expertise one would need to set up their own oil company in Pakistan, which he was eventually able to do in 1995, when he set up Bosicor Pakistan Ltd, an oil refining company.

But while Bosicor was set up in 1995, construction of its refinery did not begin until 2001, and its refinery did not start production until 2004, when its refinery in Hub, Balochistan started production. The refinery started off with a capacity of handling just 8,000 barrels of crude oil per day but grew to a capacity 30,000 barrels per day within its first year. In 2009, the company renamed itself Byco.

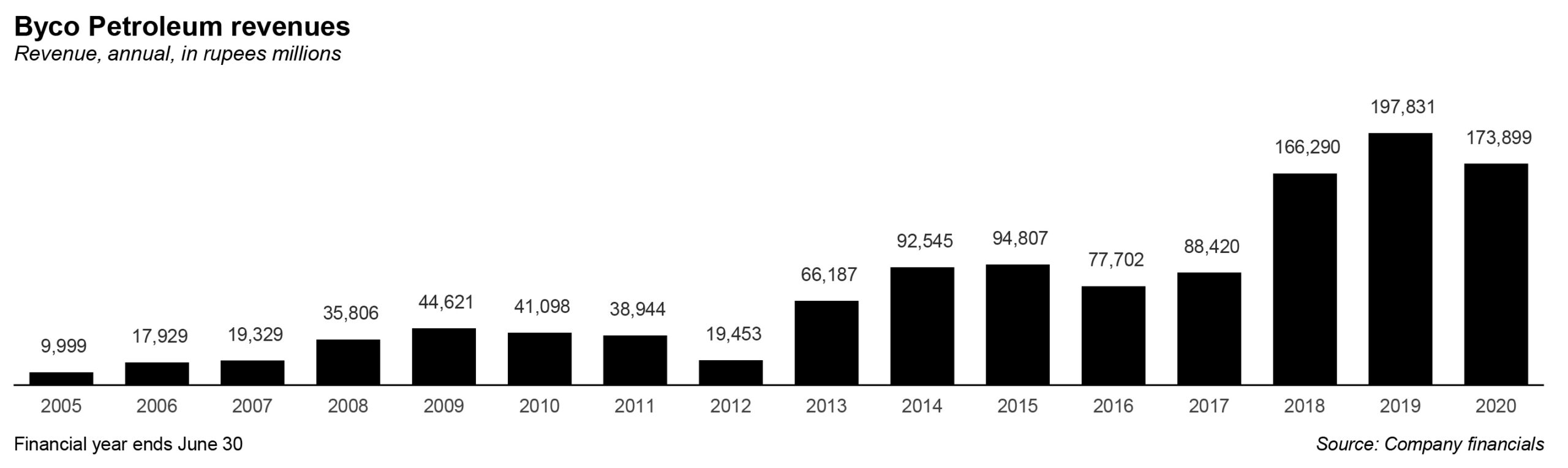

In 2007, the company launched its petrol retailing business, opening up its first petrol pump in Sukkur. In 2008, the Dubai-based Abraaj Capital bought a 40% stake in the company. The injection of that capital allowed Byco to begin work on the country’s largest oil refinery, with a capacity to handle up to 120,000 barrels of oil per day. That refinery was completed by 2012, and became part of the publicly listed entity of the group by 2017.

Combined with the enhanced capacity of its first refinery of 35,000 barrels per day, Byco’s total capacity to refine oil is about 155,000 barrels per day, making it the 105th largest refinery company in the world, and the largest in Pakistan. Previously, the largest refinery company in Pakistan was the Pak Arab Refinery Company (PARCO), which is a 60-40 joint venture between the governments of Pakistan and the emirate of Abu Dhabi, and has the capacity to refine 100,000 barrels per day of crude oil.

The next largest refinery company in Pakistan after Byco is the Attock Group, which owns the Attock Refinery as well as a majority stake in National Refinery Ltd. If PARCO is able to finish its massive Khalifa Refinery – with a capacity of 250,000 barrels per day – in Gwadar, it will regain its title as the largest refinery company in Pakistan.

That second refinery is a reflection of the company’s ambition. In 2007, Byco was the smallest refinery company in Pakistan. By 2012, it was the largest, an achievement that the company invested $750 million in securing.

To do this, the group imported a refinery that was owned by Chevron in Milford Haven, UK. The entire refinery was taken apart and moved to Byco’s 600-acre site in Hub, Balochistan where it has since been re-assembled and re-calibrated to operate in the Pakistani environment. It took almost two years – from 2007 to 2009 – just to move the refinery and another three years to reassemble it.

The refinery business – and why Byco is different

It is not just the size of Byco’s refinery that is impressive. What distinguishes this refinery is its ability to process crude oil beyond a level that other refineries in Pakistan offer.

Tucked away in the massive refinery complex at Hub is a small segment called the isomerisation unit, the first of its kind in Pakistan and the pride and joy of the company’s engineers. This unit allows the refinery to convert 12,500 barrels per day of naphtha into motor gasoline, commonly known as petrol. That may not sound significant, but in the world of refining, it is big news.

Here is why: one of the most astounding things about the oil refining business is just how much of it is unprofitable. A plurality of the product produced by most refineries in Pakistan yield negative gross margins, meaning that they sell for below the price of the crude oil that went into making them.

Approximately 50% of the refined products produced by most Pakistani oil refineries are furnace oil, liquefied petroleum gas, and naphtha. All three yield either negative gross margins or at best flat margins. Refineries make their money off diesel fuel and petrol, and even there, the margins are quite narrow, often in the single digits.

Taken together, petrol and diesel constitute about 50% of the refinery’s production. If, however, a refinery is able to add the roughly 8% of its production that is naphtha and yields negative gross margins into petrol – which yields positive gross margins – the refinery will significantly boost its profitability. Byco’s refinery may be old, but it is the only one in Pakistan that has the capacity to do so, which makes it one of the few that actively engages in value-addition in the refining business.

The collapse of furnace oil

So oil refining, as you can see, is a tough business. You make a loss on a substantial portion of your product because so much of it is furnace oil. “Around 25-30% of our product turns out to be furnace oil,” said Mohammad Wasi Khan, a member of Byco’s board of directors, in an interview with Profit.

Now imagine if you could not even sell that product for a loss. What would that do to your overall cash flow and profit margins? That is the situation the Pakistani oil refining business finds itself in.

“A few years ago, the local demand for furnace oil was around 9 million tons, of which 3 million was produced locally. The rest was imported. However, as of now, the total consumption of furnace oil in Pakistan is 2-2.5 million tons,” said Wasi Khan.

What caused that change? In a word, power. The electricity generation sector in Pakistan switched over from the much more expensive fuel source that is furnace oil to the much cheaper source that is liquefied natural gas (LNG). This was good for the economy overall because it meant Pakistan’s electricity generation costs went down, and it was also better for the environment.

For the refineries, however, it has been a devastating blow.

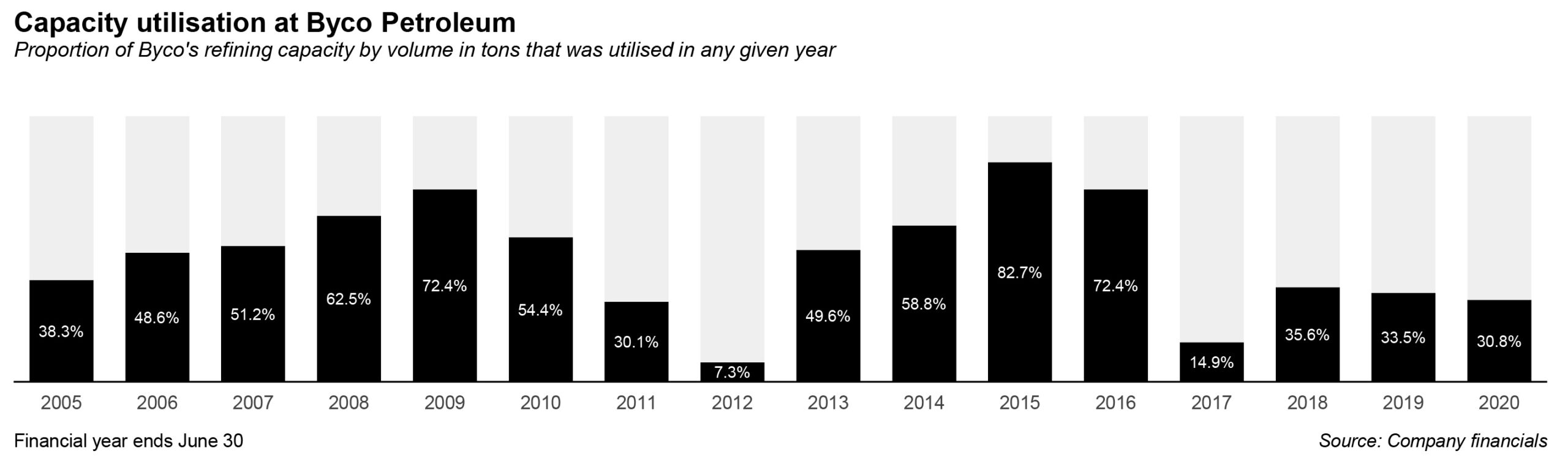

“Refineries are underutilised,” said Wasi Khan. “If they work at full capacity, they’ll have surplus furnace oil which if not sold in the country [anymore since the power sector switched to LNG], so it will have to be exported very cheaply because the global demand has decreased. The reason is because it hardly is used for power generation any more and our type of furnace oil is no longer sold as a fuel for ships because it is high-sulfur furnace oil. So, we make only that much that we can sell.”

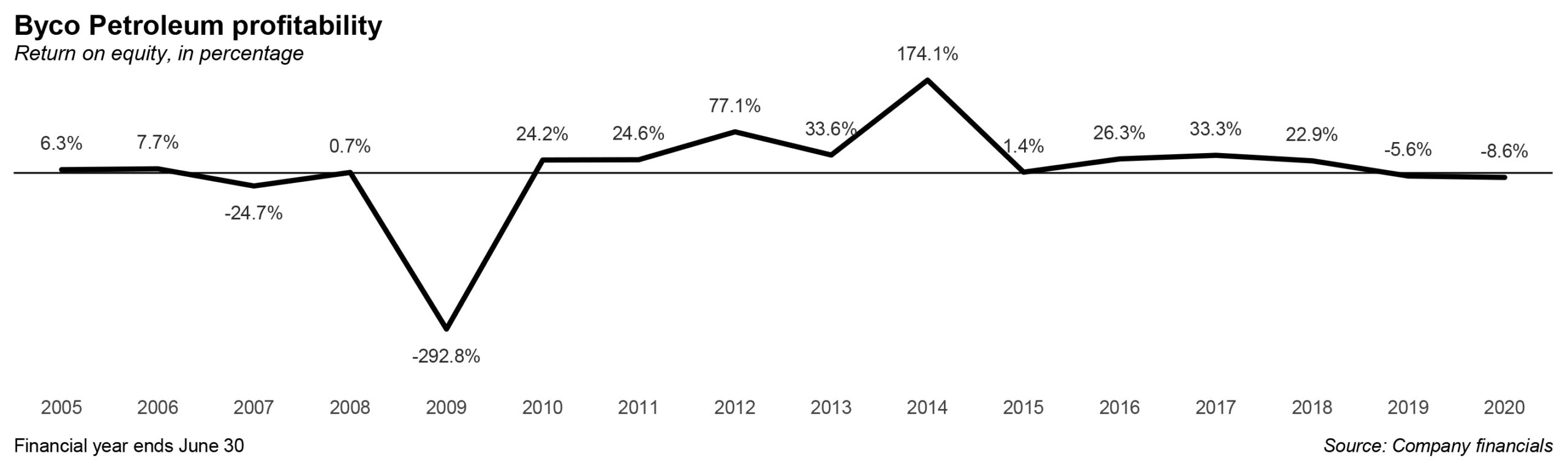

He is not exaggerating about operating below capacity. For the financial year ending June 30, 2020, Byco operated at a capacity of about 31%, and the highest it has ever operated at is 35% of total capacity. The company built up a massive refinery for a fuel mix that no longer exists, and hence most of its refining capacity has to sit idle.

Of course, the refineries have a choice. They can either continue to keep their capacity idle, or they can invest in upgrading the capacity of those refineries to be able to further crack furnace oil to become lighter hydrocarbons that can be sold for higher prices. “Lubricant can be made from [furnace oil] and asphalt for roads. If you further crack it, you can make gasoline and diesel,” said Wasi Khan.

Cracking refers to the chemical process by which heavier hydrocarbons present in crude oil are broken down into lighter hydrocarbons. Light and heavy in this case refers to the number of carbon atoms per molecule in each product.

But of course, it only makes sense for refineries to make that investment if they know that they will be able to sell that refined product at prices that make sense for them. Unfortunately, the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA), which has the power to set prices in the country, does not have a pricing mechanism that is conducive to making that sort of investment.

The pricing problem

In theory, the prices of oil products in Pakistan are ‘deregulated’. In practice, however, the government is still in charge of setting prices.

“The government says [oil prices are] deregulated,” said Wasi Khan. “I have said this to the government and to [former Prime Minister] Shahid Khaqan Abbasi too that “Aadha teetar aadha batair” is the problem. Either go full teetar and regulate. There’s no harm. It was done in the past. Even go on and nationalize the industry or go on and change prices every 3 months. Everything used to work then too. So, if you want to regulate, go all in. If you do not, leave it onto us.”

“The best thing for the country will be to completely deregulate the downstream oil industry. Market-based pricing means [the government] can’t decide the prices. For instance, if there is an oil company that is free to set its prices, it will decide based on its inventory and its inventory price. It won’t sell at a loss and will compare its prices to companies around it. Sometimes it might sell at a lower cost, sometimes higher. Ideally you need a regulator, which could be OGRA, to check if there are cartels and if they’re fleecing consumers.”

Wasi Khan also said that he believes that OGRA could be effective at regulating margins without having to rely on price ceilings. “If you are leaving it free, then there is no point. Also, OGRA knows the price of the product in the Middle East. Diesel import with duties should be for Rs100 per litre, let’s say. If someone is selling at Rs105 or Rs110 per litre, that is not fleecing… The best thing to do would be put a cap on the margins as a percentage,” he said.

If you cannot set your own prices, what incentive do you have to invest in improving your production capacity? There is no guarantee that the government will allow you to earn the cash flows you will need to pay off that investment.

The shortages and brittle supply chain

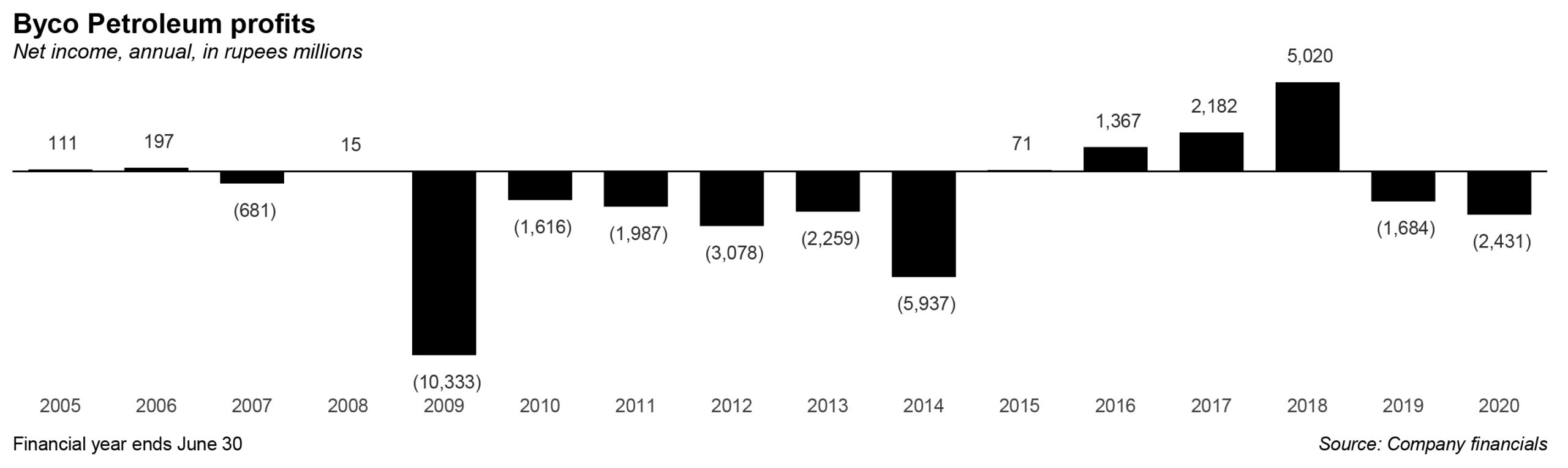

The problem with the regulatory mechanism goes way beyond pricing, however. If companies are not able to charge the prices they need to, they tend to run heavy losses, which is evident in the fact that all refineries in Pakistan frequently post negative net income.

That would be bad enough, but the problem gets much worse during periods of high price volatility, particularly when global oil prices are declining. In periods like that, governments are often anxious to be seen as passing on the full effects of a price decline immediately to consumers, even though the oil consumed on any given day in Pakistan is usually something that was imported one month ago, and the prices for which were likely agreed three months ago.

If the global price suddenly drops from $60 a barrel to $40 a barrel, but the inventory for the oil marketing companies was bought when it was $60, the government cannot reasonably expect the oil companies to suddenly drop to the new prices. In a reasonable regulatory framework, that lower price would be allowed to be phased in with the same lag as exists in the supply chain: three months or sometimes even more.

Alas, the government does not believe in being reasonable when it comes to oil prices and often tries to force oil companies to immediately pass on the effects of the lower prices and absorb any ensuing losses. And that problem of forced losses is made worse by the energy sector’s intercorporate circular debt – which is also caused by the government’s bad management, in this case of the electricity sector.

The circular debt means that oil companies in Pakistan are running on low cash reserves since so much of their payments are stuck in that circular debt. That means that when they are hit with a shock like the forced losses of lower oil prices, they simply lose the ability to access cash, which means they cannot pay for the oil they need to import, and so they import far less than the country needs, which results in massive oil shortages.

This has now happened at least twice, once in early 2015, and again in 2019, with the country effectively running out of petrol for several days.

Now, the government owns about two-thirds of the oil supply chain, through its ownership of Pakistan State Oil, as well as the oil exploration and production companies such as the Oil and Gas Development Company (OGDC), Pakistan Petroleum (PPL), Pakistan Refinery (PRL), and PARCO. And yet, somehow, they manage to blame the private sector for the supply shortages.

The blame game, and the allegations against Byco

In their interviews with Profit, the Byco management and board of directors were careful not to cast blame on absolutely anyone for the constant barrage of accusations the company has faced in the press in recent months. Yet, even a cursory glance at the nature of the allegations – and the incentives of the players involved in the industry – make it obvious as to who stands to gain from such allegations.

Think about it this way: you are a civil servant who runs the petroleum ministry and have supervisory authority over OGRA. You are, in effect, in charge of the country’s oil and gas supply chain, and there is a sudden shortage of petrol that you should have foreseen, and for which the media is searching for someone to blame.

What would you do? If you had integrity, you would come forward, accept responsibility, apologise to the public, and offer your resignation to the Prime Minister. Unfortunately, the Civil Service of Pakistan does not encourage that kind of personal accountability.

If accepting responsibility is not an option, then accepting blame is not a viable option either. The next logical move is to adopt the strategy articulated by American political dirty trickster Roger Stone: “Admit nothing, deny everything, make counter accusations.”

It is the “make counter-accusations” part that Byco has found itself the target of, with government reports simultaneously accusing the company of wrongdoing while providing the data that clearly indicates otherwise. There are the NAB inquiries that seem to target Byco as being responsible for cash flow difficulties at Pakistan Petroleum, even though Byco accounts for a tiny fraction of PPL’s receivables.

And so, the accusations and scapegoating of Byco represent a fundamental problem with Pakistan’s oil and gas sector. The government owns most of it, badly manages it, does not want to admit its own failures, and does not want to give up control of it, and so it continues to level accusations at private sector companies, one of the largest of which is Byco.

If our hypothesis is correct, here is what you can expect to happen: one by one, the government will accuse every major oil and gas company of wrongdoing of one sort or another, claiming fraud or malfeasance. One by one, every private sector oil company will find itself in the hot seat. Miraculously, that same scrutiny will never quite shine on the state-owned PSO.

Strange how these things just seem to work out that way.

“. Byco’s refinery may be old, but it is the only one in Pakistan that has the capacity to do so”

All the refineries in Pakistan have installed isomerization units. Please do a basic fact check before publishing

It’s an interesting news story.

Paid article by Byco management. Due to firms like Byco and HBL, Profit Pakistan is able to keep paying salaries of its news writers, analysts and editors. Otherwise would have been shut down ages ago.