It is September 2019, and Mumtaz Hasan Khan is a confident man. And why wouldn’t he be? He is the chairman of Hascol Petroleum, a company that has been doing exceptionally well over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2018, Hascol saw its topline surge by an astounding 52.7% per annum, from Rs7.9 billion to Rs234 billion. And while there are concerns over a looming crisis, all he has to do is keep a steady ship sailing smoothly.

“There is nothing to worry about for the company. There come different phases in the life of individuals and companies. And with the grace of Almighty, we will overcome the crisis. We have a very good management team,” he said back then.

But fast forward to today, and nothing remains the same. At the end of a year full of drama and chaos, Mumtaz has been fired, and the company has shuffled CEOs twice. The company’s CFO resigned multiple times, and as of now, the seat remains empty. In 2019, the company made a loss of Rs 26 billion for the year ending December 30. In its recently released report for the third quarter of 2020, it has managed to make a loss of Rs20.9 billion.

The company is crippled by severe debt, which stands at Rs58 billion. The 14 banks Hascol owes money to are now forming a consortium to get the company potentially restructured. As one source put it, Hascol’s rise and fall is a reminder of the damage that can be shaped by obtaining heavy loans and giving unnecessary discounts to achieve growth.

Sitting on top of the rubble from the destruction of the past year is Alan Duncan, a former Member Parliament of the United Kingdom House of Commons that has remained minister of state in both the May and Cameron cabinets in the United Kingdom. A staunch conservative politician with links stretching back all the way back to Margaret Thatcher and John Major, more telling for the purposes of our story is his past as a business executive. He broke out from Oxford working for Shell, but more famously found his sea legs working for notorious financial criminal Marc Rich, who was indicted in the United States on federal charges of tax evasion and making oil deals with Iran during the Iran hostage crisis.

As Profit lays out what happened to Hascol this year, and all the drama that the company kept seeming to land in, two former CEOs – Saleem Butt and Aqeel Ahmed – declined to comment for this story. And the current CEO, Adeeb Ahmad, tried to avoid Profit as best as he could, saying anything he had to say could be found in the latest report, and did not want to answer the trouble within the financials.

First, some history

Over the course of barely a year, Hascol cracked and wilted until it finally broke open at the seams. What makes this downward spiral more shocking is that it is not something that has long been on the cards. In fact, Hascol used to be considered a rising star within the oil marketing companies (OMCs). Hascol was incorporated as a private limited company in 2001. The company received its oil marketing license from the government in 2005, which allowed it to purchase, store, and sell petroleum products like high speed diesel, gasoline, fuel oil and lubricants. In 2007, the company was converted into an unlisted public company. In 2014, it was finally listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange.

Hascol’s fortunes changed in 2009, when veteran energy executive Saleem Butt took over as the executive director and chief operating officer of the company. Under Butt’s leadership, the company was able to expand its access to debt. Previously banks had been somewhat less forthcoming with this new entrant in the oil market, but as COO, Butt established a strong relationship with Summit Bank, one of the smaller banks in the country, to begin extending the company the credit needed to expand. From then onwards, Hascol started to become bigger every year with Saleem Butt at the helm of affairs, first as COO, and then as CEO. Interest grew in the company, and in 2015, Dutch energy giant Vitol acquired a 15% stake in the company, and bought another 10% in 2016 to become the largest shareholder in the company. Hascol and Vitol also entered into a joint venture deal for marketing of LNG with a 30-70 ratio respectively. By 2017, Hascol rose to become the second largest oil marketing company in the country, overtaking both Shell and Attock Petroleum, and behind only the government-owned PSO.

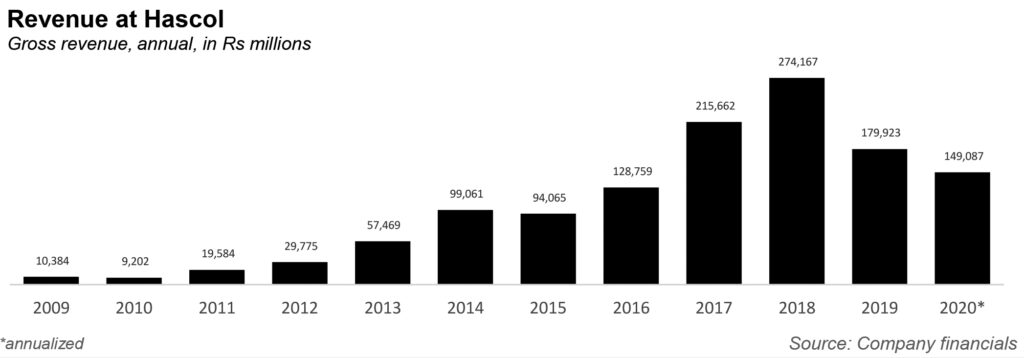

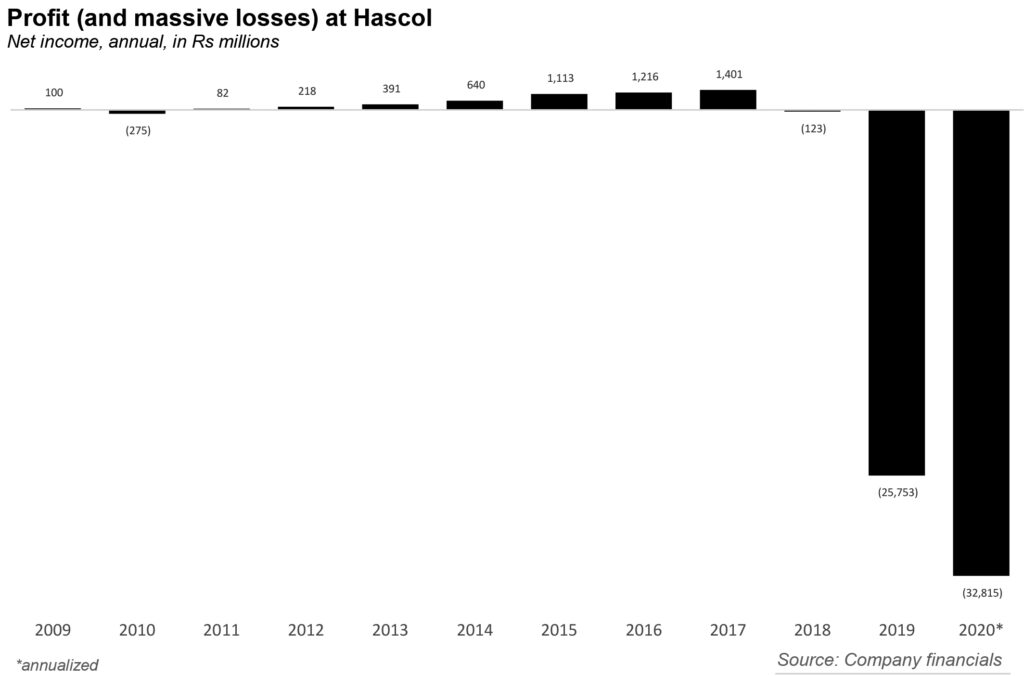

Over the course of its existence, the company has always managed to increase revenues. It saw a revenue increase from Rs 10.3 billion in 2009, to Rs 274 billion in 2018, with there being only a slight dip in 2015. Indeed, between 2010 and 2018, the company saw its revenues climb at an astonishing average of 52.7% per year (Hascol Petroleum’s financial year ends December 31 of each year.) For most of its existence, it has just about managed positive net incomes, as cost of sales has also been quite high. It experienced a loss of Rs275 million in 2010, and Rs123 million in 2018, but in the three years prior to 2018, it has a net income greater than Rs2 billion.

What in the world went wrong in 2019

And then 2019 happened. Typically, when a figure is that absurd, we avoid making a graph of it, for risk of spoiling the aesthetics of the magazine, but we have included it here just to show how truly bizarre that year was for Hascol. Revenue dipped from Rs 274 billion in 2018, to Rs180 billion in 2019 and net income went from a loss of Rs123 million in 2018, to a loss of Rs 26 billion in 2019. Also observe net cash flow: Hascol had one remarkable year in 2015, where net cash flow stored at Rs22 billion, but in 2018, its net cash flow was negative Rs12 billion, which fell to negative Rs16 billion in 2019.

By way of explanation, at the time, Hascol’s chairman had very little to say. “There has been significant volatility in the international oil market, and serious currency devaluation in the local economy. This has combined with punitively high interest rates, which has placed a severe burden on the company’s cost of financing,” he wrote in the company’s annual report that year.

Read between the lines, and what you get is what we now know very well, that the government regulates prices of oil products sold in the country and does not adjust prices fast enough to keep pace with the extent to which prices change in international markets. As a result, companies like Hascol are sometimes stuck with inventory that they bought at much higher prices and are forced by the government to sell at much lower prices.

The year 2020

So what happens when a company has a catastrophic 2019 and then has to deal with the coronavirus to follow up from that? The recently released third quarter data was not pretty to say the least.

For the nine month period ending September 30, 2020, the company’s net revenue stood at Rs99.4 billion, significantly lower than the Rs130 billion achieved in the same nine month period in 2019. The company’s loss for the nine month period ending September 30 stood at an astonishing Rs20.9 billion, compared to a loss of Rs14.4 billion in 2019. If one looks at the annualized data, then the company’s net loss for the year 2020 stands at Rs32 billion.

In 2020, with the repeated pattern of poor performance, the company decided to elaborate in its quarterly report, writing that “during Q1 2020, the shareholders injected Rs8 Billion as additional capital, to bolster the operations and address the liquidity position of the company, both of which had been adversely affected in fiscal year 2019. But due to the lockdowns imposed by the government to tackle the C-19 situation; not only the sales volumes decreased due to a drop in consumption of oil products, the unprecedented fall in oil prices and devaluation of currency also had a severe dampening effect on the Company’s financial performance.”

Do Hascol’s explanations hold up?

Admittedly, the year 2020 has not been good to most major oil companies. Consider Shell Pakistan. For the nine month period ending September 30, its gross revenue stood at Rs135 billion, (compared to Hascol Rs99 billion) while its net loss stood at Rs6 billion (compared to Hascol’s loss of Rs20.9 billion).

Both Attock and Pakistan State Oil have financial years that end on June 30 (Hascol’s financial year ends on December 31). But if one looks at the quarterly report for the first quarter for both those companies i.e. the quarter that ends on September 30, the figures tell a different story.

In Attock’s case, sales stood at Rs46 billion, while net loss stood at Rs562 million. The same figures for Hascol for the quarter of September 20 are very different. Gross sales for that quarter stood at Rs30 billion, while net loss stood at Rs3 billion. PSO is the only company in this case which managed to post a profit during this period. In PSO’s case, sales stood at Rs333 billion, while net profit stood at Rs5 billion.

While other companies have posted losses, they are not close to the scale of financial losses that Hascol is experiencing. So what else is plaguing the company?

The mysterious write-off and other bad practises abound

The year 2020 has been full of controversies for Hascol. For instance, in October 2020, the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA) suspended its marketing and distribution license in KPK. Apparently, Hascol had been operating illegal and unauthorised storage and selling of petroleum products (petrol and diesel) at Amangarh Depot, despite OGRA’s clear directives for the stoppage of operation of Amangarh Depot.

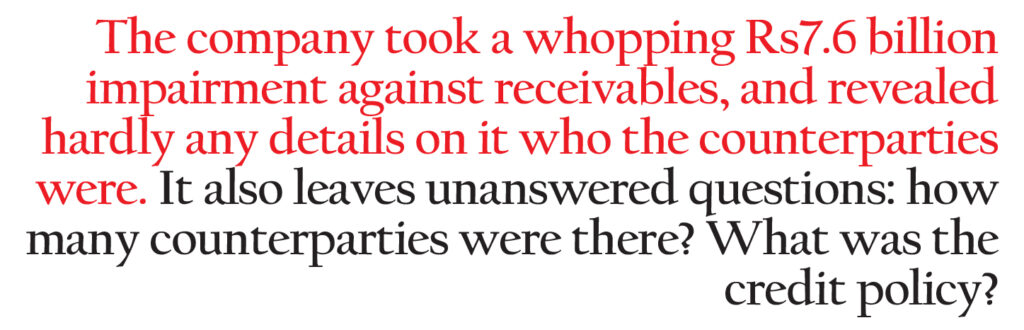

But perhaps most importantly, the company took a whopping Rs7.6 billion impairment against receivables, and revealed hardly any details on it who the counterparties were. It also leaves unanswered questions: how many counterparties were there? What was the credit policy? Was the parent company, Vitol, aware?

To understand how this could have happened, it helps to know how petrol is sourced and distributed. Roughly, most OMCs in Pakistan source petrol either through refineries locally or through imports. A company like Hascol does both. The oil is then sold either to dealers (who are petrol pump owners) or to end consumers through company operated pumps. Hascol has a mixture of both dealer-operated and company-operated pumps, though in its case, the dealer operated is far larger.

In the OMC business, one can only sell direct through one’s own pumps, or through dealers that operate one’s company-branded pumps. If it is the latter, then the usual credit terms are three to seven days and sometimes collateralized by guarantees or bonds. Which leads to the ultimate mystery that the market is asking: who was allowed this much credit by Hascol?

One explanation floating in the market: that the petrol was actually sold to a middleman, who then “dumped” this stock into other OMCs petrol stations, such as PSO and Total etc.

Before we try to uncover this middleman, let us pause for a moment and first understand what dumping is and how it takes place. Let us say there is OMC A. Its dealer operated pump is committed by law and contracts of Pakistan to purchase petrol and diesel from OMC A. The price at which that transaction happens is at a regulated price established by the federal government. ‘Dumping’ is when another company, say OMC B, basically decides to sell to OMC A’s dealer at a lower price, which OMC B is not legally allowed to do. Why would OMC B do this? If both OMC A and B are sourcing their fuel from a refinery in Pakistan, then they are receiving it at the same price and there is no reason to dump. But if OMC B is able to procure smuggled fuel or otherwise offshore fuel at a better price, then they have a price advantage, and they can ‘move’ that fuel. OMC A may sell to their own dealer for Rs100, but OMC B may come to that dealer and sell at Rs98. This transaction typically happens off the books, and in the middle of the night.

According to one source, some of the amazing volatility in certain OMC sales is not just related to a lack of supply, but also related to the fact that there has been a crackdown on this dumping practise. And the rumour about Hascol persists, in part due to the perception that dumping within the OMC market has been particularly prevalent in the last few years.

Another way OMCs could dump and make money is by manipulating the inland freight equalisation margin (IFEM). The government of Pakistan has set the price of petrol the same across the country, whether you are buying it in Gilgit or Karachi. Obviously to transport petrol all the way to Gilgit is a lot more expensive than to Karachi. OMCs report their sales to the government, and charge the government what is called IFEM; or a way of getting reimbursed for freight costs.

This business can be abused if an OMC starts to show a lot of sales in Gilgit, instead of in Karachi i.e. charge long distance freight charges, even when the product was being transported and sold to dealers of other OMCs at shorter distances. This system benefits the dumping OMCs, dealers, and middlemen; in some cases, dealers practically became mini OMCs in their own right. Needless to say, this is illegal.

The middleman

Profit tried to ask Adeeb Ahmad about the impairment, who only said that the party’s name was one SR Fuel Experts, and that they had owed Rs 8 billion to the company, and said any other information was confidential.

While Profit could not find information on SR Fuel Experts, but there is a company called Fuel Experts, which formed in 2011, that specializes in the distribution and transportation of oil and gas products. Its CEO is Hamid Khan, who, according to his LinkedIn, worked at Shell Pakistan from 2003 to 2010.

Now, here is where it gets interesting. The company called ‘Fuel Experts’ isn’t confidential at all. In fact, the company, along with the founder Khan, were named in the ‘Report of the Inquiry Commission on Shortage of Petroleum Products in Pakistan’, headed by FIA Additional Director-General Abubakar Khudabaksh, and commissioned by the Pakistani government in July 2020, to probe the shortage of petroleum products. That damning 155-page report leaked in December asked for the dissolution of the industry regulator for a litany of failures starting from 2002.

On top of pointing out malpractices of the OMC industry in general, that report said two things of particular relevance to Hascol. First, it confirmed the theory of smuggling and dumping, noting it is an open secret that petrol products are being smuggled into Pakistan from the western border of Taftan, Iran. The second thing the report went on to mention were the dealings of Hamid Khan with Hascol. “Hamid Khan is reported to have extensive business dealings with Hascol,” it reads. “However, after reportedly defaulting on huge credit in Hascol, he has now established a company by the name Fuel Experts Pvt Limited. Although Fuel Experts is not an OMC, it is dealing with the supply of petroleum products by procuring it from different OMCs (read Hascol) and openly supplying it to several retail outlets countrywide on his self generated invoices and delivery notes in violation of OGRA rules.”

At least according to this report, Hascol seems to have lost a lot of money on this one middleman. Or did they? While Adeeb Ahmed was reticent, Profit did manage to contact the head of sales at Fuel Experts, Wasif Khan. The tale he told was very different, and according to his version of events, while Fuel Experts did do significant business with Hascol, they did not owe Hascol anything.

“Fuel Experts have paid off all invoices that were raised by Hascol in the name of Fuel Experts and one can check the official books of Hascol to confirm this,” said Khan while maintaining that his company is not liable for any other dealings of the company. “Where is the old CFO and where is the old CEO?” he asked rhetorically. When asked if his company was involved in dumping on behalf of Hascol, he naively explained “If an old PSO pump owes money to PSO and is not in good financial health, then PSO would not supply fuel to this pump. Now the owner of the pump will not close his business just because of this. He will obviously look for other suppliers of fuel”.

But something still does not make sense. If it is not Fuel Experts that owes Rs8 billion to Hascol, then where did this money get lost? And why would a company like Hascol allow one middleman such lenient credit terms? Unless of course, if the middleman was only a frontman for Hascol own management at the time. Indeed, a related party to the controversy heavily insinuated that that is exactly the case, and that Hascol used to maintain multiple sets of books to do just that.

We are told that Hascol has managed to get a stay order against the Securities and Exchange Commision of Pakistan, which wanted to conduct a thorough investigation into the accounts of the company but with recent reports of the National Accountability Bureau and FIA taking interest in the affairs of OMCs, things may heat up soon.

The banks get fed up

The banks are not happy with Hascol, and they have been publicly getting passive aggressive with them. Take Meezan Bank for example, which in its analyst briefing for their fourth quarter of calendar year 2020 results, made a special mention to Hascol alone. The bank said that the higher provision charge in the fourth quarter mainly relates to Hascol, which has a negative equity and has been delayed on its debt servicing obligations.

As early as late 2019, Hascol had become the target of rumours that banks had stopped lending to the company. To understand why, one needs to remember that much of the company’s success before 2018 had been based on huge loans. The company’s rise had relied on a very aggressive pricing strategy where discounts were offered to capture market share. This allowed for huge investments in retail outlets and storage facilities.

Then, as already mentioned, the company in 2019 began to suffer losses because of the macro-economic issues, such as devaluation and plummeting inventory prices. Yet despite these issues, according to sources, the company kept on borrowing for working capital. but allegedly diverted these loan proceeds for other than their initially stated use. So rather than managing its working capital requirements, the company continued to expand its retail network on a fast track basis, adding almost 100 outlets per year with these short-term borrowings. This made the company over-leveraged and caused a mismatch in borrowings. Currently, the company’s debt stands at Rs58 billion, and it owes money to at least 14 banks.

Part of the problem with Hascol is a larger problem with companies borrowing from banks in general. In Pakistan, there is no disgrace attached to defaulting on bank loans. This has in part to do with the lengthy judicial process it takes for banks to retrieve their money from defaulters, often between five to 10 years. This gives a defaulter a lot of time to go about their business, while the case is pending in court. As per one source, this practice gives a sense of liberty among industrialists, many of whom are politically connected as-well, and can drag the legal case on for years.

So, what can a bank do in this situation? Banks in Pakistan usually try to make the company operative through restructurings, rather than demand their money. And that is exactly what happened.

In its quarterly report, Hascol said “…The Company’s lenders agreed to partially convert short-term debt to long-term (which completed subsequently in September, 2020) to improve the Company’s debt maturity profile. However, due to the subdued economic conditions and volatility of the oil markets, the expected results were not achieved.”

Similarly, Hascol also said it was in talks with banks (though it did name which banks) to partially convert debt into equity and restructure all of the company’s short term debt into long term facilities. The banks seem to have no choice but to play ball.

Auditors resign

Most unusually, the company’s auditors, EY Ford Rhodes, resigned as co-auditors last year. It is always a cause of concern when an auditor resigns – particularly when it is one of the ‘big four’ firms: Deloitte, PwC, Ernst & Young, and KPMG.

Essentially, it boils down to this: it is actually very stressful to be an auditor for a Pakistani company. There is immense pressure by the global heads of the accounting companies on their local Pakistani subsidiaries to apply an extra layer of scrutiny on Pakistani companies. Why? Because the world simply does not trust them. It is an unfair assumption perhaps, but it does explain why auditing companies are extremely wary of having or real estate companies in Pakistan as clients. It is simply too dodgy.

Simply performing poorly is no indication of fraud. But since Hascol has performed so poorly, it is also likely under immense pressure to perform, and show better financials. EY seems to have wanted a fair amount of distance between itself and Hascol. When contacted, the CEO was unwilling to disclose why the auditor resigned, despite multiple attempts at contact.

After the sugar inquiry report, international accounting firms have also come under their fair share of criticism for giving a clean chit to companies that were clearly maintaining two books of accounts and making off the books sales. According to a senior member of the accounting fraternity, the problem in Hascol was with the opening balances and the records presented by the management very obviously not enough for EY to verify these independently. EY Ford Rhodes also declined to comment for this story citing client confidentiality.

Instead, Grant Thornton Anjum Rahman Chartered Accountants alone reviewed the books and expressed doubt about the proposed plan to fix the financials, saying: “The management’s assessment highlighted that the liquidity of the Company is dependent upon the proposed restructuring arrangement of the Company’s overdue financial liabilities. However, we were unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to support our conclusion in respect of the proposed restructuring. These condensed interim unconsolidated financial statements do not reflect any adjustment that would be required should the Company be unable to continue as a going concern…we have not been able to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to form a conclusion on these condensed interim unconsolidated financial statements.”

…and management resigns as well

In 2019, Mumtaz Khan had this to say: “The same management was delivering excellent results. Between 2011 and 2017, we were growing very rapidly. They are competent people and they are all professional people. There is no one from my family like a nephew or son or something. The company has been run professionally just like Shell or Total…It is a professionally run company. That is why Vitol has taken shareholding. The management, they are good people, competent people, honest people. And they have been delivering good results often. Every company faces bad times.”

So much for that. The year 2020 has been a series of revolving doors for major management members.

First, let us look at the CEOs. On February 19, 2020, Saleem Butt resigned, citing personal reasons. On February 24, Waheed Ahmed Shaikh was appointed CEO. Shortly afterwards, on April 2, Aqeel Ahmed was appointed as CEO. On September 17, he was reappointed as CEO – except on September 22, just a few days later, he was resigned as the CEO of Hascol Lubricants, a subsidiary, and Adeeb Ahmed was made the CEO instead

Now, for the CFO (an important job, considering the state of the company’s financials. On February 19, Khurram Shehzad ceased to be CFO, and Muhammad Ali took his place. On July 17, the two CFOs were swapped out (Khurram became CFO again). Then on September 10, Shahid Bhutto became CFO, before resigning from that position on January 22. The position is yet to be filled.

And finally, the chairman. On March 31, Mumtaz Khan was replaced with Alan Duncan. Of all the people mentioned so far, he has the most colourful past life: he was a director of Vitol Dubai Ltd., the parent company. He had studied at Oxford with former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, helping her campaign for the President of the Oxford Union (which she won). He then stayed in close contact with her, and was one of the few people she emailed right before she died in 2007.

That is not his only connection to Pakistan. During 1990-92, following the invasion of Kuwait, he was a major supplier of refined products to Pakistan following the termination of the country’s supplies from Kuwait Petroleum. In 2001, Pakistan opened up an investigation into the supplies: allegedly, British firm Vitol sold 280,000 tonnes of ‘contaminated’ oil to Pakistan State Oil in 1993, picked off the coast of Kuwait and contaminated it with sand and salt. The oil caused £100 million worth of damage after one of Pakistan’s main power stations broke down in January 1994, plunging Lahore and Karachi into several hours of darkness. According to a Guardian article from the era, “At the time of the blackouts, the Pakistan government, then ruled by Benazir Bhutto, began an inquiry into the scandal that was subsequently dropped with little explanation.”

Duncan, clearly, moved on: he was International Development Minister 2010-14, and Foreign Minister 2016-19. And now, he is the chairman of the equally worrisome and controversial Hascol.

The future

So, concerns about dumping, debt, and an interesting chairman: what will Hascol do now? In its report, the company said it would try the following: significant reduction in operating costs, recapturing and growing sales volumes and market share, disposal of non-core assets, shoring up working capital and raising of additional equity to reduce leverage and address negative book equity. And on March 1 of this year, it sold two properties it held in Dolmen Sky Tower, as part of its restructuring to improve cash flows.

Good for them: but what about the people who lost their money in the meantime? Consider this: between January 2018 and November 2018, the share price of Hascol stood between Rs270 to Rs310 range. On November 1, the price stood at Rs287. By December 31, it crashed to Rs148. And by September 2019, it had fallen to a shocking Rs22. As of April 23, 2021, it is now trading at Rs9.13.

Considering their track record, their insistence to keep things secretive, can anything the company says now be trusted? One sure hopes so, for the sake of their lenders and investors at least.

Thank you for all the insights.

Old news

Phoenix shall rise again .!!!

History repeats itself. Mumtaz Hassan has a history of defrauding banks. Earlier he connived with Philips and got them off the hook with purchase of Whirlpool brand for one pound and immediately shut don the operations. While SCB and ANZ Grindlays were paid by Philips International, the three local banks were left with PR 300 Million of write off.

Fuel experts is a medium sized distributor and can never take credit worth 8 billion. 8 Million maybe alot for them.

I wish the author had reached out to the directors, particularly independent directors and also the audit committee and the risk committee. Given there is enough evidence to suspect negligence/illegality and possibly fraud these people 1. have questions to answer about how this was allowed to happen under their watch and 2. an obligation to investigate and pursue perpetrators of any wrong doing for recovery for benefit of shareholders that have been affected. For too long, directors – particularly independent directors have not been held to account in Pakistan. Perhaps, the SECP should investigate this. Or maybe its time for some shareholders to pursue this legally. Don’t even get me started on the auditors.

Apparently Vitol and founder promoter got their investment back and showed it as bad debts nd inventory losses.

A good story , with a reasonable financial flair..

Good Article.

Tip of an ice berg

You just follow the the cash flow out and you habe your answers!

Tip of an ice berg

spalling concrete