It is not often that a small bank puts up a portion of its lending portfolio for sale in Pakistan. It is even rarer for that to happen and for it to matter to the broader banking industry’s competitive dynamics, but that is exactly what is happening with the announcement that Silkbank is selling its consumer lending portfolio, and that the leading contenders, at least at the moment, are Habib Bank Ltd (HBL) and Bank Alfalah.

In a press release issued on May 3, the bank announced that the two much larger banks are interested in acquiring Silkbank’s consumer lending portfolio, which is made up of credit cards, running finances, and personal installment loans.

“The Silkbank Board of Directors has requested the State Bank of Pakistan to grant permission to both HBL and Bank Alfalah to conduct due diligence of the Silkbank Consumer Accounts portfolio prior to its possible acquisition by either of these banking entities,” the bank said in its press release.

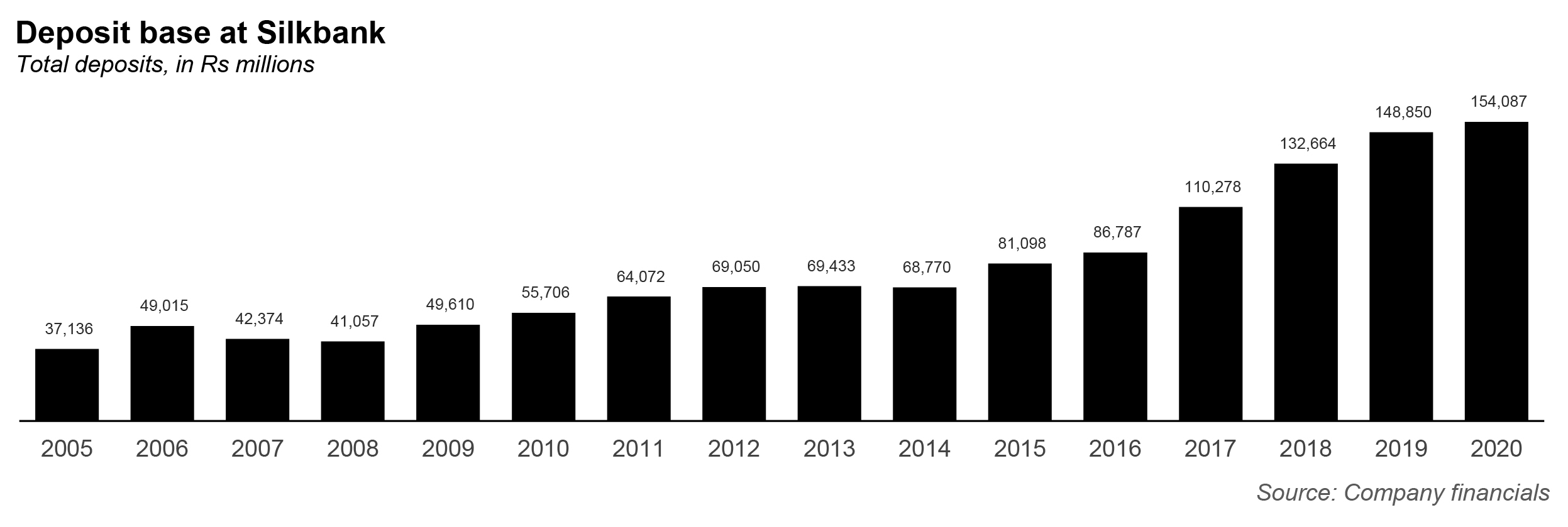

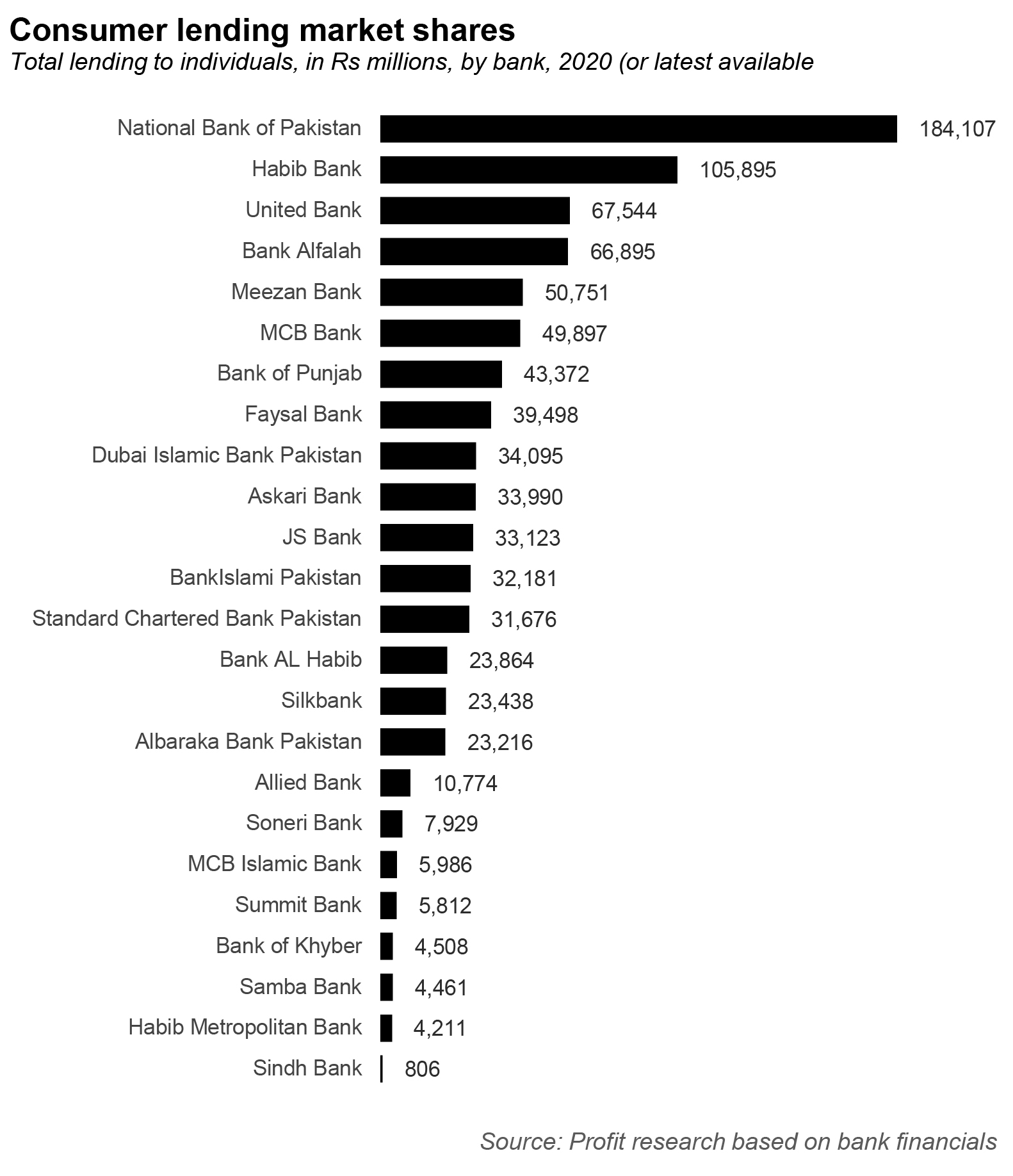

As of the close of 2019, the most recent period for which Silkbank’s detailed financial data is available, the consumer lending portfolio at the bank stood at Rs23 billion. In the grand scheme of the Pakistani financial services sector, that is hardly anything, accounting for just 2.6% of the industry’s total consumer lending.

But it matters for three reasons. Firstly, the portfolio consists of a high margin credit card business that has a relatively low default rate, by Pakistani banking standards. Secondly, Silkbank has consistently been one of the leading consumer-facing lending banks in Pakistan, so a sale of its consumer lending portfolio represents a significant shift in the bank’s strategy. And finally, the two banks leading the charge to buy it are interesting contenders. Which one of them ends up buying it could mean some very interesting things for the shape of competition in consumer finance in Pakistan.

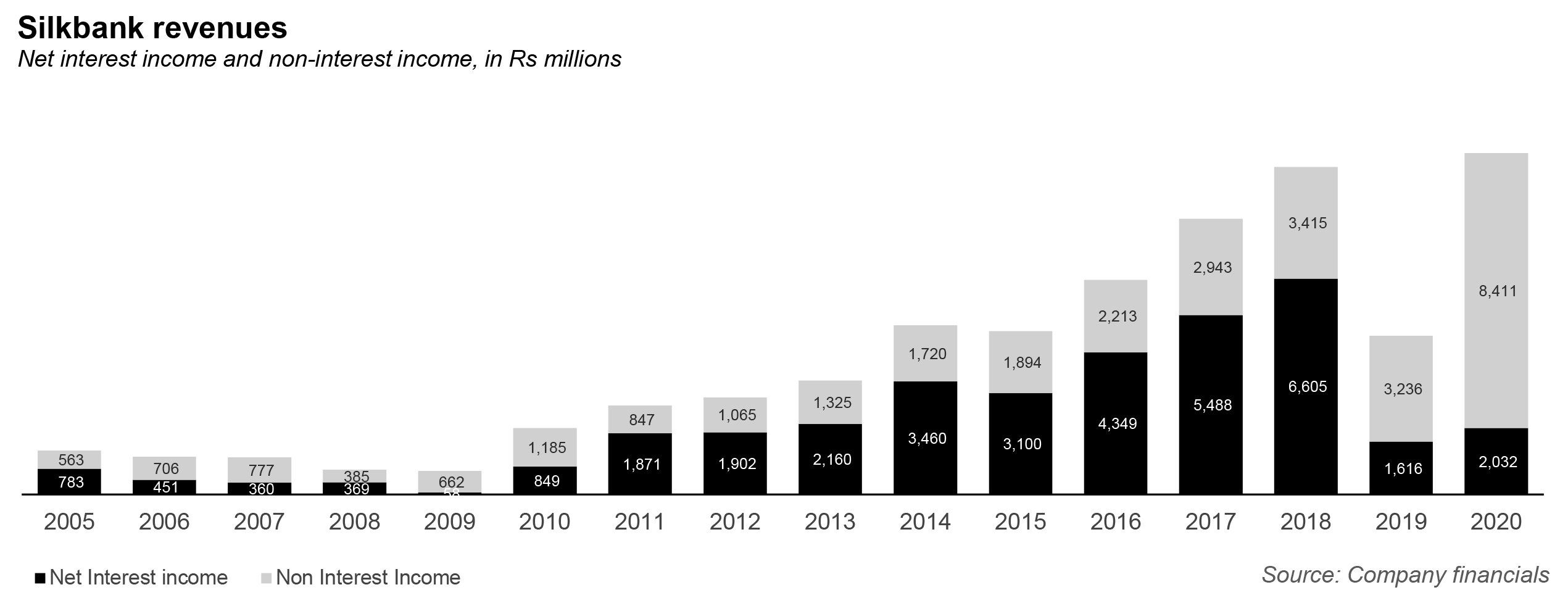

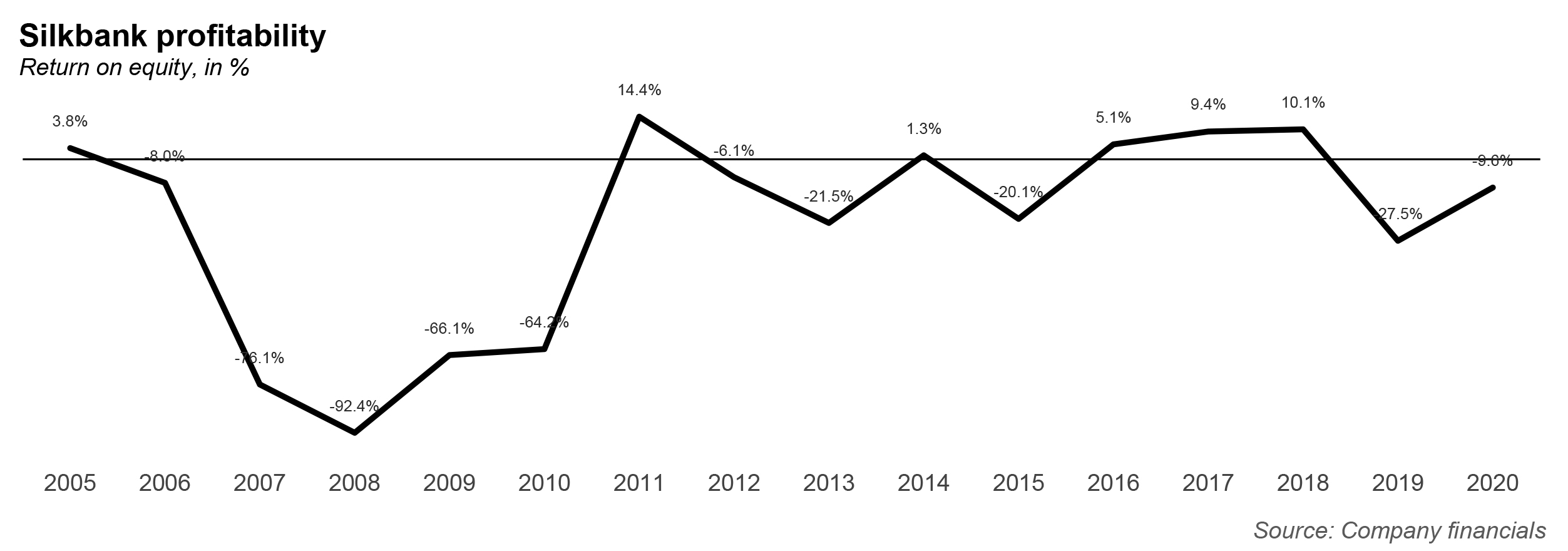

One additional caveat for this story: Silkbank has had some struggles with profitability and growth in recent years, and those will be the subject of a future in-depth feature about the bank. This story, however, will focus more on how it has built this attractive asset and what its sale would mean for the broader banking industry in Pakistan.

Tarin, consumer banking, and the making of Silkbank

The most important thing to know about Silkbank is the one thing everyone already knows about it: it was founded by former – and now again current – Finance Minister Shaukat Tarin. To understand what the bank does well, and why its consumer lending has been a strong competitive advantage for the bank, one needs to understand Tarin’s professional history. Tarin is by now a legend in the world of Pakistani finance, but his specific achievements are relevant to understanding how he has been able to build up Silkbank.

Shaukat Tarin was born in Multan to an Army family and grew up in cantonments across Pakistan. He completed an MBA from the University of Punjab, and almost immediately began a banking career in 1975, joining Citibank in Pakistan, rising through the ranks of the New York-based global financial institution in both Pakistan and abroad.

Among the stints that Tarin had in Pakistan was leading a legendary team at Citibank that practically invented consumer finance in the country, introducing credit cards and personal loans and vastly expanding the scope of mortgage lending and auto lending in Pakistan.

After 22 years at Citibank, he was tapped by the government of Pakistan in 1997 to lead the restructuring of Habib Bank, then a state-owned basket-case of a bank that had a balance sheet with more holes than a block of Swiss cheese. Over the next three years, Tarin surgically repaired the bank’s balance sheet and got it on a footing that allowed the government of Pakistan to be able to privatise it for a profit rather than having to give it away for free, which is what they did with Allied Bank.

He then joined Union Bank as its CEO, brought on and given a 5% equity stake in the bank. This was the heyday of the Musharraf-era boom in consumer lending, and Tarin used every ounce of his Citibank skills to make Union Bank into a consumer banking powerhouse. It was that prowess with consumer finance that made it an attractive asset for Standard Chartered Bank, which bought Union Bank in 2005 for Rs29.4 billion ($490 million).

In short, Tarin knows consumer finance in Pakistan probably better than anybody. So when he took over Silkbank, it was always going to be a key part of his strategy.

The creation of Silkbank

Silkbank began life in 1994, as the Prudential Commercial Bank, before being acquired by the Saudi Pak Industrial and Agricultural Investment Company (SAPICO) in 2001, which gave the bank a new name: Saudi Pak Commercial Bank. Shortly afterwards in 2008, the bank was bought yet again, by a consortium of individuals, including Tarin.

The acquisition of Saudi Pak Bank was supposed to be a continuation of Tarin’s successful streak as a bank executive. One can hardly blame him for wanting to keep going. He was just 53 at the time he successfully exited Union Bank, having already knocked it out of the park with CItibank, and Habib Bank before that. Why would he want to slow down now?

Tarin was able to put together that consortium, led by Japanese investment banking giant Nomura, to acquire Saudi Pak Bank. Timing, however, was not on Tarin’s side, and by that, we do not just mean the fact that the transaction happened right before the 2008 financial crisis (though, of course, that probably did not help).

The Saudi Pak acquisition closed on April 1, 2008. Almost exactly six months later, on October 8, Tarin was appointed federal finance minister by President Asif Ali Zardari at a crucial time in Pakistani economic history. In other words, Tarin was not able to take charge of his own bank, and left his brother Azmat Tarin as CEO.

Of course, the investors who had backed Tarin were very unhappy about not having him at the helm of the bank they had just helped him acquire and so Tarin stayed in the finance minister job for only 16 months, despite being universally regarded as having done a good job, having shepherded through the negotiations on the transformative 7th National Finance Commission Award and the financial components of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution.

The consortium that owned the bank, meanwhile, changed composition. In 2015, the Arif Habib Group acquired a stake. According to Silkbank’s latest annual report for the year ending December 2019, around 62.39% of the bank’s shares are held by the consortium that has management control. That consortium today consists of the Arif Habib Group, which holds 28.23% of the bank, Shaukat Tarin (who holds 11.5%), the International Finance Corporation (which holds 7.74%), Zulqurnain Nawaz Chattha (one of the owners of Gourmet Foods, who holds 7.47%), Nomura European Investment Ltd (3.93%) and Bank Muscat, which holds 3.48% of Silkbank’s shares.

Between 2008 and 2020, the bank’s CEO was Azmat Tarin, Shaukat Tarin’s younger brother. He was replaced in August 2020 by Shahram Raza Bakhtiari, the head of retail banking at Silkbank. The bank is presently headed by Nabeel Anjum Malik, who is the acting president and CEO, while Bakhtiari waits for approval from the central bank.

Consumer lending prowess

As we stated above, Silkbank has had its fair share of challenges. What is undeniable, however, is the bank’s prowess in consumer lending.

As of September 30, 2020, the latest period for which the bank has released financial statements, Silkbank had issued 163,496 credit cards, one of the largest credit card businesses in the country, with balances of around Rs5.4 billion.

You might think credit card balances of Rs5.4 billion is not much as an asset, but consider this: credit cards frequently have interest rates north of 30%, meaning that the bank is frequently earning a net interest margin in the range of 15-20% on them. On Rs5.4 billion, that would amount to as much as Rs1.1 billion in revenue for the bank.

And this is a growing business for Silkbank. It booked an additional 72,000 accounts in 2019, with roughly 16,000 readyline accounts, 11,000 installment loan accounts, and 45,150 fresh credit cards. The total ENR (ending net receivable, also defined as the total money owed to a company by its customers minus the money owed that will likely never be paid) increased to Rs20 billion for consumer banking. According to the bank, that gave it a 38% market share among comparable banks.

Its credit card activation rate jumped from 83% to 87% (which according to the bank is the highest activation rate in the industry). The credit card utilization rate also increased from 27% to 31%, while retail spending on credit cards jumped 28% year-on-year to Rs28.3 billion. In other words, people are not just applying for Silkbank credit cards: they are activating them and then actually using them for spending.

Silkbank clearly put a lot of effort into innovation: for instance, it kickstarted a free gymnasium program for Silkbank platinum credit card holders. It relaunched a 5-year loan, 4-year markup scheme in personal loans on media. And it revamped and added additional features to its ready line business (credit for emergency needs).

The bank seemed quite set on maintaining its edge in consumer banking, despite the bank’s other difficulties. For instance, in the annual report of 2019, the bank said that it wanted to reduce the real estate portfolio, close loss-making branches, and increase consumer loans, in order to improve CAR. And even in the financials for the nine month period ending September 2020, the bank said that it wanted to dispose of Other Real Estate Owned (OREO) assets, and use the proceeds to further grow its consumer banking segment.

We cannot emphasise this enough: it is unheard of for Pakistani banks to be this interested in their consumer lending business. Ever since the crash of 2008, the banking sector had effectively sworn off consumer lending, like the hard-charging party-boy who wakes up after blacking out the night before and promises to never drink again… and then actually goes ahead and quits drinking.

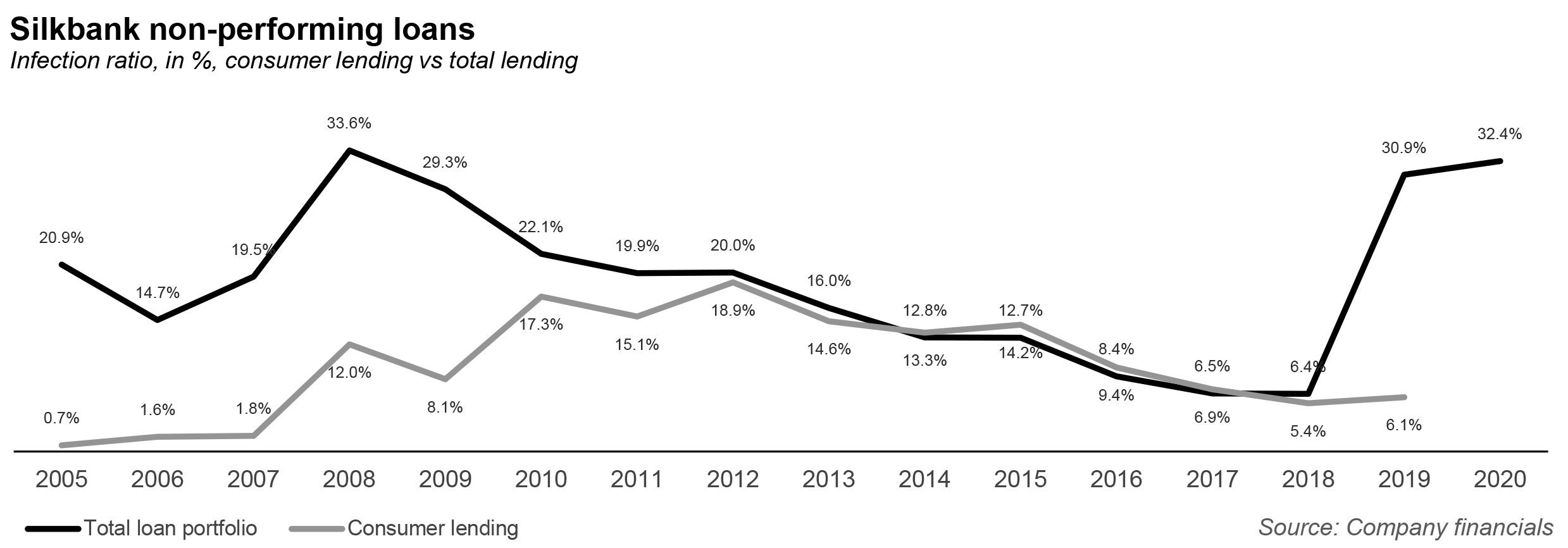

And, here is what makes it even more interesting: Silkbank has managed to contain its bad loans in the consumer lending space to a relatively low level. As of the end of 2019, the bank’s infection ratio in its consumer lending business – the proportion of its loans that were in default – was just 6.1%. That may be high by developed market standards, but it is very low for Pakistani consumer finance.

But it gets better: Silkbank’s consumer lending portfolio has a lower default rate than its overall lending portfolio. And this has been true for almost the entirety of the bank’s history, and most of the time since Tarin took over the bank.

This is truly extraordinary because it means that the bank is better at lending to Pakistani consumers than it is at lending to Pakistani businesses. That is practically unheard of. Nearly 22% of the bank’s lending is to consumers, and with those kinds of default rates and net interest margins, one can see why the bank is so enamoured with its consumer finance business.

According to Shankar Talreja, deputy head of research at Topline Securities, Silkbank is known to be an outlier when it comes to consumer banking.

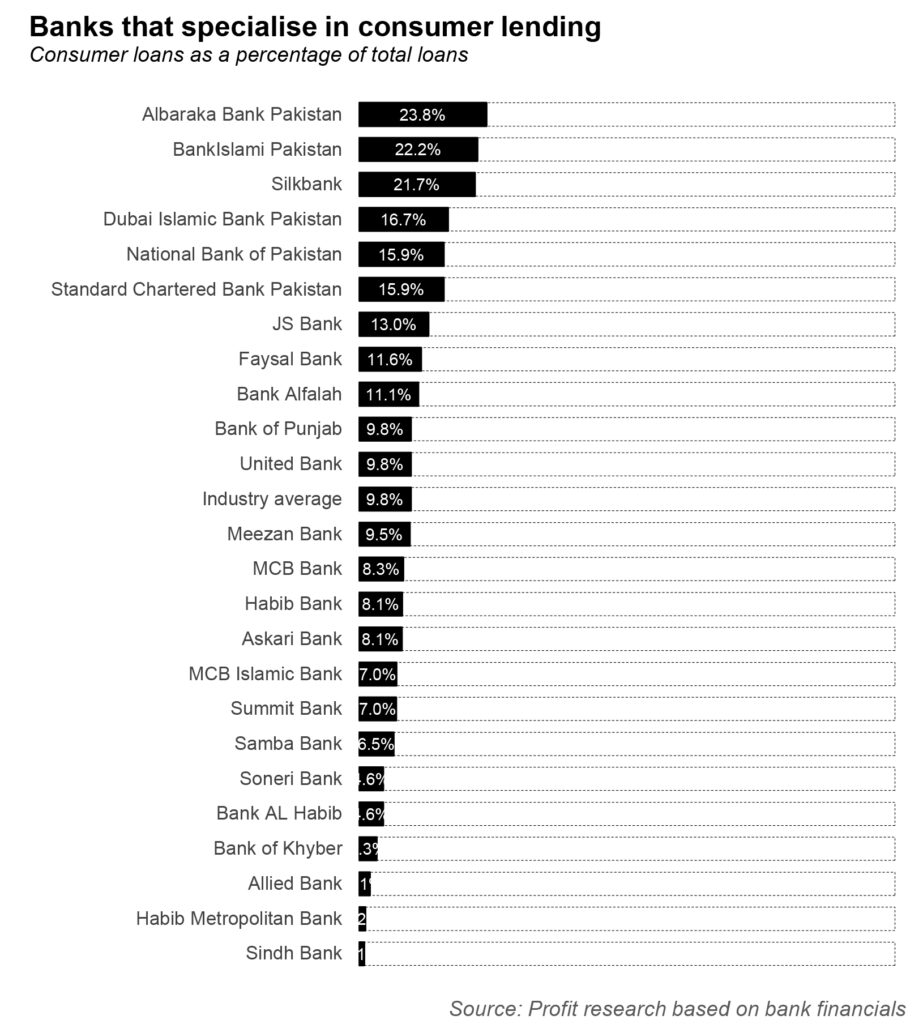

Talreja is not wrong. Profit analysed the numbers, and Silkbank has the third-highest concentration of consumer finance in its lending portfolio among all banks in the country, with only Albaraka Bank Pakistan and BankIslami Pakistan being higher. And Islamic banks are generally forced into consumer lending by virtue of the relatively scarce supply of Shariah-compliant government bonds for them to invest in.

Why is Silkbank selling its consumer business?

Which makes the potential sale of its darling segment all the more interesting. As the notice said, “The potential sale of its portfolio will allow Silkbank to strengthen its Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), rebuild profitability and enhance value for all stakeholders.”

Silkbank has had an unusually bad run of defaults on its other lending book and needs the money to shore up its capital reserves, which have been below the levels required by the State Bank of Pakistan for some time now.

Now, why is this important? Silkbank stressed to the PSX – and by extension, everyone worried about this bank’s future – “The potential sale of its portfolio will allow Silkbank to strengthen its Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), rebuild profitability and enhance value for all stakeholders.”

Then, Silkbank went on to say that its ‘focus on individual customers’ is reflected by the fact that the bank had “retained its market share and is one of the leading personal loans and credit card issuers in the market.”

Why who wins this asset matters

The first contender is HBL, which already has a well developed consumer banking segment, which is the second-largest one in the industry, behind only National Bank’s state-mandated consumer lending portfolio. As of December 31, 2020, Habib Bank had Rs106 billion on gross consumer loans outstanding, or about 8% of its total lending book.

The next contender is Bank Alfalah, which is narrowly in fourth place in terms of consumer lending, with a Rs67 billion portfolio as of the end of 2020, representing 11.1% of its lending book.

Whether it is HBL that wins the bidding war or Bank Alfalah will mean very different things for the consumer finance space in Pakistan.

There is debate among analysts as to what would be Habib Bank’s goals with this acquisition. Some analysts said that the sale of the portfolio would enhance HBL overall consumer segment exposure and its profitability; others argued that the portfolio would be negligible to HBL’s total assets. Either way, as HBL’s own annual report pointed out, there has been an uptick in e-commerce in Pakistan overall, and especially more so in the pandemic, and thus more credit cards are being used. An expanded consumer portfolio would be able to take advantage of that trend in consumer spending.

Indeed, just this month, HBL became the first bank in Pakistan to allow automatic approval for e-commerce transactions on credit and debit cards on its network, meaning that consumers no longer need to call Habib Bank to ask for their credit cards or debit cards to be authorised to be used online.

And HBL has been growing its consumer business. In 2020, the consumer banking business grew by 25% to Rs75 billion, despite the disruption caused by the pandemic. Of that, personal loans remained the largest product, at 50% of the total consumer lending portfolio. Auto loans in particular grew by 52% in 2020, with HBL’s market position in this real, jumping from fourth to second. And HBL’s credit card business grew by 22%, and total spending on those cards increased by 12% from 2019.

What about our second contender, Bank Alfalah? The logic behind Bank Alfalah seeking to enter this space is obvious: Bank Alfalah began its life in Pakistan as a consumer-focused bank, something it had to shed since 2008, but an attribute that is still baked into the bank’s DNA. That it is the fourth largest consumer bank in the country is likely something that the Bank Alfalah management wants to remedy in a hurry.

If they were able to buy out the portfolio, it would make them the third largest consumer lender in Pakistan, and only narrowly behind HBL, meaning the competition between Bank Alfalah and HBL in the consumer lending space would heat up considerably.

Incidentally, Bank Alfalah and HBL are also two of the leading banks in the merchant acquisition business, meaning they give out credit card processing machines to merchants and process their payments for them, a highly lucrative and rapidly growing business in Pakistan. If they were to begin competing in the card issuance business – in addition to their already cutthroat competition in the card processing business – that could mean good things for both businesses and consumers that rely on credit and debit card payments.

According to Faizan Kamran, research analyst at Arif Habib Ltd, an investment bank, Bank Alfalah is known to have a strong asset quality. “[The sale] can help Alfalah further grow its consumer business as they already focus a lot on this segment,” he said. And the annual report’s future outlook did mention this: “We will work hard to regain and grow our market share in low cost deposits, consumer products and SME financing.”

Boon to electronic payments?

Despite the attempts to build non-card-based payment methods, the most common form of electronic transactions remains the use of credit and debit cards online. If HBL wins this auction and becomes the dominant card issuer, while already being the biggest merchant acquirer in the country, that will make it very difficult for other banks to compete in this space, meaning that the incentive to promote the use of credit and debit cards among both consumers as users and businesses as acceptors will diminish.

If, however, Bank Alfalah wins the auction for Silkbank’s card business, it will become more of an even rival with HBL, and will force its bigger rival to spend more resources in competing for both the merchant acquisition business as well as the card issuance business. For businesses looking to accept credit cards, that could mean lower transaction fees. And for individuals, that could mean more discounts and incentives to use their cards.

Both of those could speed up the adoption of electronic payments, and therefore increase the pace of growth for e-commerce in Pakistan, already being accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic. In short, this battle for Silkbank’s credit card business could mean big things for the e-commerce industry in the country, as well as the domestically focused consumer-facing tech industry more broadly.

At what price?

Good question: just about nobody knows what the exact valuation of the consumer portfolio will be. There is some historical precedent to an acquisition of a consumer portfolio: Citibank. The story has a number of coincidences. For one, Citibank was also run by Shaukat Tarin in the 1990s. And secondly, both HBL and Bank Alfalah applied for due diligence regarding the consumer portfolio – just as in this case.

Here’s what happened: as an American bank, Citibank was badly hit by the US financial crisis of 2008. Subsequently, Citibank Pakistan suffered: in 2007, the bank’s infection ratio was just 2.1%, but by 2010, the infection ratio was 21%, and peaked in 2012 at 25.4%.

To counter this, Citibank decided to sell off its portfolios. In 2009, the bank sold off its mortgage lending portfolio to BankIslami Pakistan. Then, in November 2012, it decided to sell off its credit card and consumer lending portfolio to HBL, a transaction was approved in February 2013. At the time, Citibank closed 12 of its 15 branches in the country.

The consumer portfolio was bought for Rs1.9 billion (net of specific provision) at the time. According to the 2012 annual report of Citibank Pakistan, the bank’s gross advances stood at Rs24.4 billion, of which Rs4.5 billion fell under consumer and SME classification.

Here’s the crucial takeaway from the Citibank story: it worked. The bank was able to focus on corporate and investment banking, and saw its profits climb to pre-2008 levels again. As of 2019, nearly 80% of Pakistan’s multinational companies bank with Citibank.

Will Silkbank be similarly able to recover? It is not a bank that traditionally has focused on corporate banking – in fact, its entire shtick has been consumer banking. And with that portfolio gone, it will be interesting to see how the bank manages to reinvent itself, and turn a new leaf – if it can.

Dear Meiryum,

Assalamoalukum! hopefully you will be fine and enjoying best health, i have read your entire blog/article on Silk Bank, as you analysed every stage and things of bank is absolutely appreciated and you have lightened the path that is in darkness, especially your words are above to enough for the peoples who are effected, by reading your blog/article definitely they can fix their decision to get loss are further more wait to achieve the success.