Revealed preferences are a beautiful thing: they give you proof of what people really think, regardless of what they say.

If you ask people to say what they think about Pakistani attitudes towards internet-based payments, they will tell you that Pakistanis do not trust the internet to make payments, that we are a cash-loving people who will take a very long time to adjust to making internet-based payments. That is what you call stated preference.

Revealed preference – or what people’s actual behaviour suggests they prefer – is practically screaming the opposite.

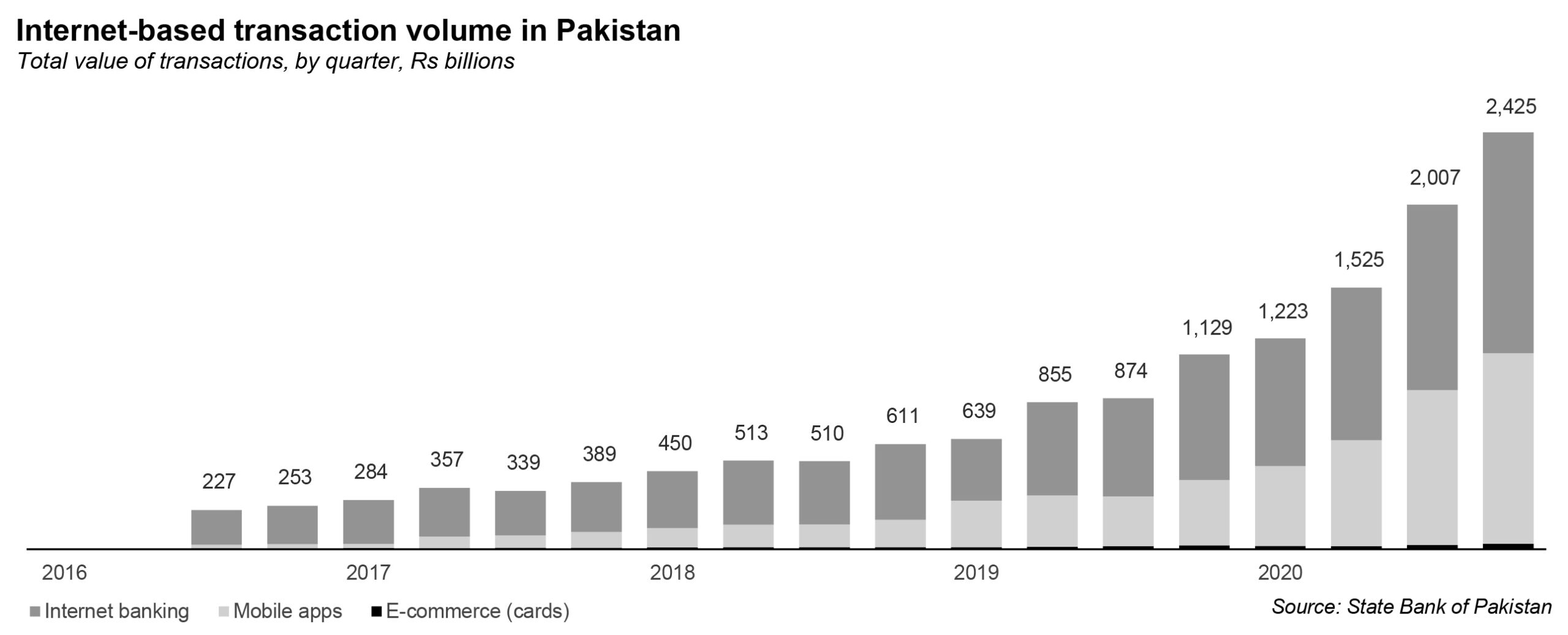

Data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is unambiguous on this point: strip out the internet-based payments system (bank websites, mobile apps, and e-commerce), and the rest of the country’s payment system (mostly cash, ATMs, and branch banking) has grown at just 6.7% per year on an annualized basis, between the third quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2020. Inflation during that period, by the way, averaged 7.5% per year, meaning the real purchasing power of the non-internet-based payments system went down during that period.

What happened to the internet-based payments volume during that period? They went up by an annualized averaged of 70.1% per year. And by the way, when we say internet-based transactions, we mean bank websites, bank and payment provider mobile apps, and credit and debit card transactions on e-commerce websites (excluding cash-on-delivery transactions).

The numbers get more astounding the more you dig deeper into them, and we will later into this story. But we wanted to start off by disabusing the reader of the notion that somehow Pakistanis are a cash-obsessed society. We are absolutely not. If the data is any indication, the entire Pakistani body economic is screaming in agonized unison: FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, LET US TRANSACT ONLINE!

In this story, we will start off by offering compelling evidence that suggests that Pakistanis do not use cash because they want to, but rather because the formal financial system makes it difficult to use formal non-cash payment methods. We will then examine why that is the case, followed by an assessment of the new, internet-based payments methods, including an examination of the competing infrastructure providers for payments in Pakistan.

Finally, we will look at the recent spurt of venture capital interest in Pakistani payments providers, and whether or not that has the potential to change the landscape of Pakistan’s payment infrastructure.

Cash is easy, mobile is easier

For this story, we have utilized the State Bank of Pakistan’s quarterly reports on the payments systems, from the third quarter of 2016 through the fourth quarter of 2020. The reports extend much further back into the past as well, but the data appears to be compiled using a different methodology in prior years, and we included only data from the years where it seemed most directly comparable. Unless we specify otherwise, all growth rates mentioned in this article refer to the total value of transactions, not volume.

We also felt this was the most pertinent period to examine, since this is also the time when Pakistanis began to gain access to the internet in large numbers, following the auction of the 3G and 4G mobile broadband internet spectrum, which gave tens of millions of Pakistanis access to the internet for the first time.

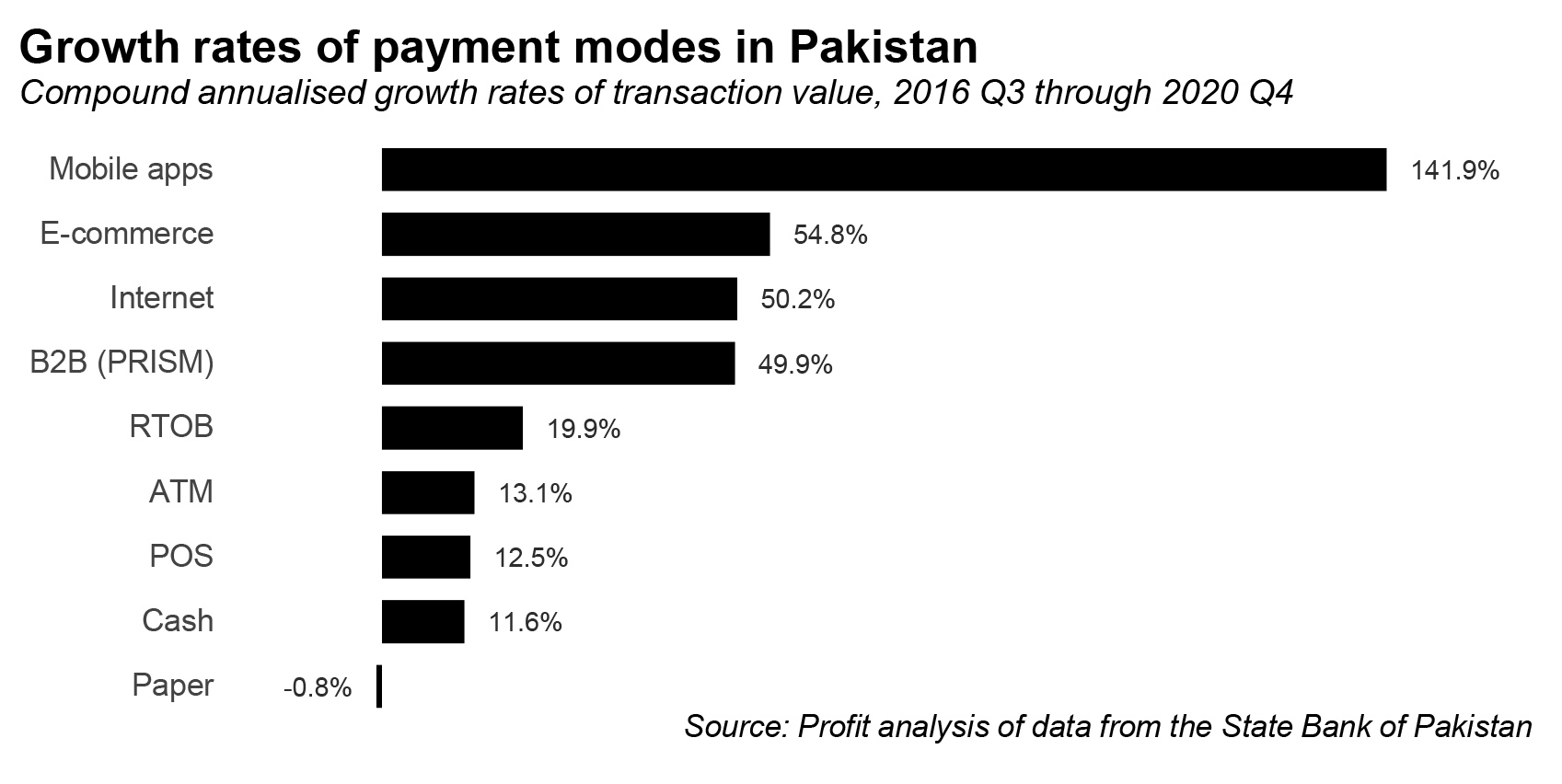

That being said, let us dig into the story that the data are telling us. There are two things immediately obvious at first glance. The first is that the paper-based system of cheques, deposit slips, travelers’ cheques, etc. is dying. It is the only part of the payments system to witness negative growth, declining by an average of about 0.8% per year during the four years between 2016 and 2020.

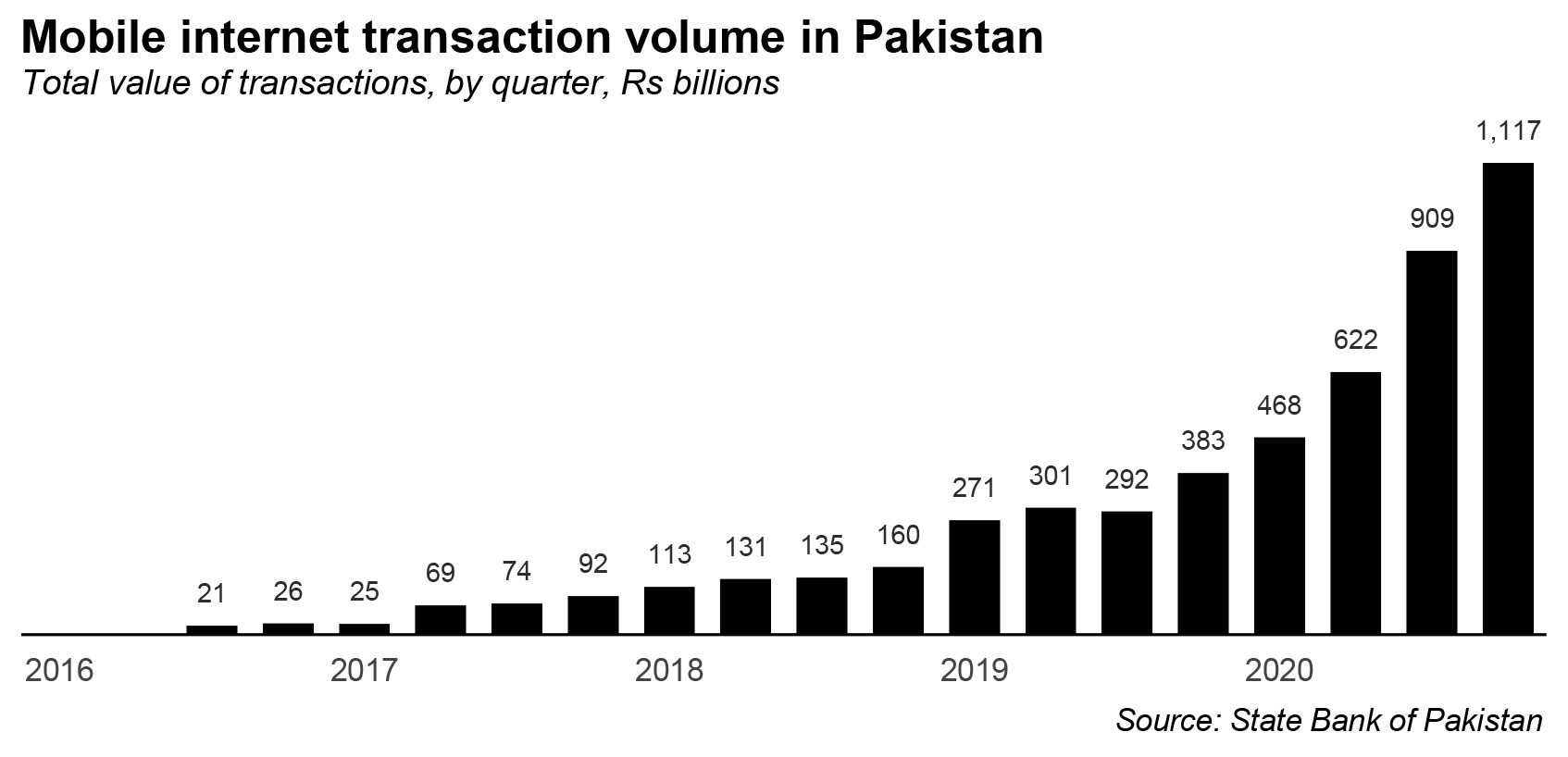

The second is that the only parts of the system that are growing at appreciable above the rate of inflation are, in order of growth rate, mobile app-based payments (142% per year average annual growth rate between 2016 and 2020), card-based e-commerce (55%), desktop browser-based internet banking (50.2%), and online B2B transfers (50%).

There are some respectable growers as well, including the real-time online banking (RTOB), which many businesses use to make transactions such as salary payments, which grew at nearly 20% per year during the previous four years. This is a reflection of the fact that more and more businesses in Pakistan increasingly want to conduct business transactions online, if only their banks would make it easier to do so.

ATM transactions as well as point-of-sale card transactions (when you pay by credit or debit card at a store) have also grown above inflation, at averages of 13.1% and 12.5% per year respectively. ATM transactions have grown by only marginally more than the number of debit cards, which rise by 11.3% per year during the same period, meaning that while more people are able to use ATMs than before, those who already have ATM cards are not necessarily increasing their usage of them.

And the less said about POS machines the better. How many times have you walked into a store or restaurant that ostensibly claims to accept credit and debit cards, but the staff there comes over to you and says “sir, we’re having a problem with the card machine. Can you please pay cash?”

POS machines are a stalling business in Pakistan, with the total number going up by less than 5% per year between 2016 and 2020. Once you factor that tepid growth in the number of store accepting cards into the equation, the actual amounts per POS machine have gone up by almost exactly the same number as inflation, meaning there has been no real growth in the volume of transactions that stores pass through cards versus physical cash.

What does all of this data tell you? It tells you that where Pakistanis have unfettered access to the ability to pay through an online system, they are using it with gusto and they are actively decreasing their use of non-cash-based formal money (cheques, etc.). And where they should be using more electronic money (POS machines), the hurdle seems to be more the accepting merchants, and not the users themselves.

Well, what about physical cash itself, you might ask? Your data may be skewed by the fact that it does not include physical cash transactions that do not touch the banking system. Fair enough. Let us take a look at what is happening with cash.

While the volume of cash transactions is not directly measured by the State Bank of Pakistan, because it issues bank notes, it has a fairly good idea of exactly how much physical cash is in circulation at any given moment in time.

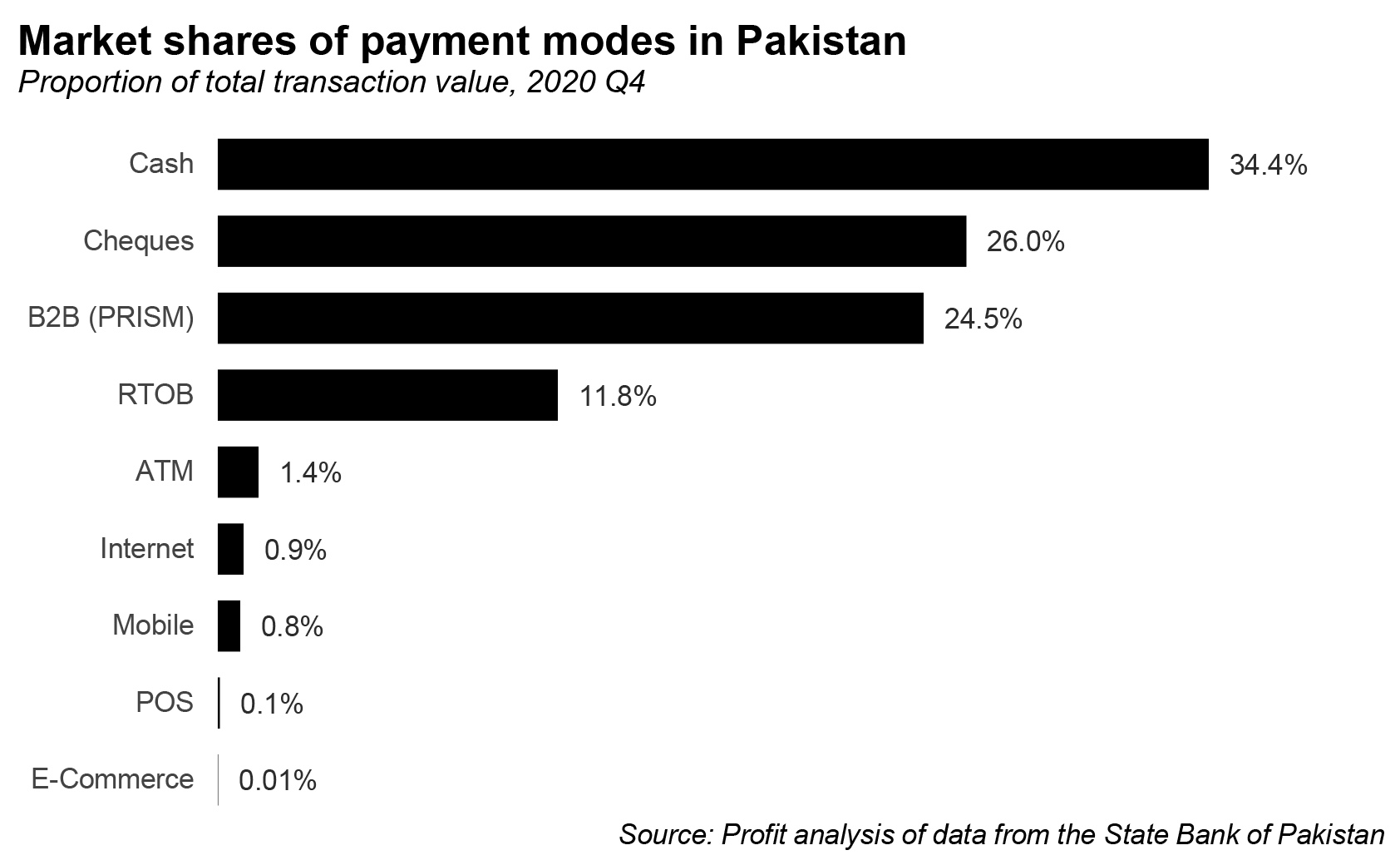

We made a simplifying assumption that the velocity of transactions involving physical cash is approximately the same as that involving the payments system, and came up with an estimate that, in the calendar year 2020, the total volume of cash-based transactions that were executed outside the banking system was approximately Rs199 trillion, or about 25.4% of the Rs780 trillion in total transactions in the economy. [Note: yes, the volume of transactions in an economy is typically several times the size of its GDP.] We also estimated that approximately 93% of all cash transactions do not involve the banking system at all.

So how much have physical cash transactions grown during the period for which we have comparable payments data. Surprisingly less than one might think. Our admittedly very simplistic estimates suggest that transactions involving physical cash grew by an average of only about 11.6% per year between 2016 and 2020. That is higher than the 7.5% per year inflation rate, but not really that much higher, suggesting that the informal sector which mostly uses the cash is not that much more robust than the rest of the economy.

In other words, the people who are using physical cash are not transacting significantly more than the people who use the non-internet-based part of banking system to transaction.

So, we can say with a reasonable degree of certainty: the internet may only account for only about 1.7% of all transactions in Pakistan right now, but there is no question that it is the only form of payments that Pakistanis clearly want to use more of than they are now. Nothing else comes even remotely close.

Why the system looks the way it does

There are significant implications of the data we have just presented. Firstly, the non-internet-based side of the banking system’s payments infrastructure is quite literally too slow to accommodate the pace of transactions the economy is demanding, and while cash remains the most popular mode of transactions, it appears people do not actually prefer it. They are just used to it.

So why is the system still so sclerotic? Why are the most convenient modes of payment still less than 2% of total transactions?

It is easy to blame the banks for this, and there is certainly a lot of room for improvement on the part of the banks, but the hard truth is this: the Zardari Administration’s delays in launching 3G and 4G internet by over five years are coming to bite the economy. Most Pakistanis who currently have the internet have it because of their mobile broadband internet connection, which was only made possible after the 3G ad 4G spectrum auctions in 2014 and 2016 respectively. By contrast, India auctioned both in 2010.

Simply put: why would the banking system invest in an internet-based payments system when the overwhelming majority of people in the country did not have access to the internet? Now that they do, the increase in transaction volume clearly shows that there is both increased desire and ability to use such means to transact.

Secondly, the banks in any country will not do anything until the regulator makes them do it. Any bank in the world – barring a handful of the most sophisticated ones – hate the idea of any deposits leaving their bank for any other and tend to make it as difficult as possible for that to happen. In other countries, the central banks often mandate more openness as a means of ensuring that individuals and businesses can conveniently transact.

The State Bank of Pakistan has some rules that do this, but it is only now catching up to the changed reality of the financial sector and the broader economy. The State Bank has long since mandated ease of interbank transfers with respect to ATMs, a mandate that directly resulted in the creation of the 1Link system in 2004 and which was later expanded to create the interbank fund transfer (IBFT) system, which allows for account holders at one bank to send money to account holders at any other bank in the country via their browser-based and mobile app-based banking systems.

And in many ways, these systems work reasonably well, the monthly outages at the major banks notwithstanding. As more and more people gain access to the internet and to bank accounts, the value of transactions on the internet appear to be going up.

The banks, for their part, appear to have noticed. One after the other, the banks have started announcing that their account holders will be able to use their debit cards over the internet without having to first call their customer services helpline to enable their cards for online transactions before each transaction. One could argue that such a requirement should never have existed in the first place, but far be it for us to quibble when the necessary finally happens. Der ayad, durust ayad.

What is missing from the system

Having said that, a lot is still missing in the existing system, and the lack of those things explains why card-based e-commerce is growing slower than, for instance, mobile banking.

The biggest hurdle in Pakistan is that the banks are not required to create open APIs (application programming interfaces) that would allow both other banks as well as non-banking fintech and other payments providers to easily build payments solutions that interact with their account holders.

The lack of such APIs and other transaction protocols, and the inability of payments providers to build anything other than users entering their credit or debit cards and authorizing each individual transaction. For example, when you subscribe to this magazine, our payment system cannot save your card information and bill it automatically every month or every quarter, or even every year. You have to manually make a payment, and since the banks’ APIs are not open, Profit has no way of linking your payment hitting the magazine’s bank account to the online system that tracks your username and password.

An open API, for instance, would allow for a payments provider to link transactions from bank accounts to accounts at online merchants such as this magazine, allowing things like subscription payments to be smoothly processed. And ideally, of course, the bank would also have payments protocols that allow for pull transactions by merchants who have received the authorization from a customer to charge their cards at recurring intervals.

This may seem like a small type of transaction, but it is not. The entire multi-trillion-dollar software-as-a-service (SaaS) industry is built on the ability to charge monthly recurring payments to both individuals and companies and the inability of payments providers to deliver such transactions is a significant limiting factor for many types of businesses in Pakistan to even exist.

Raast to the rescue.., sort of

The State Bank is well aware of these limitations and of the necessity of it playing a role in building a better payments infrastructure in Pakistan. Instead of going the route of mandating openness by the banks and then allowing payments providers to build multiple competing payments systems, the State Bank has effectively decided to build one itself, and one that will be designed not with ATM transactions (like 1Link), but instead the internet economy in mind.

That system is called Raast, and it is a simple tool that will allow for not just real-time settlement, but for complex transactions and tracking. For instance, it will allow for automatically letting a recipient know not just that they have received a payment, but that they have received it from, say Mr Siddiqui, who is paying the school fees for their son at Beaconhouse Margalla Campus. It would allow for specificity in what the transaction is for, to a degree that is not possible under the current 1Link system (though 1Link is trying hard to build it into their system), and thus would lower transaction costs and vastly improve the experience of making payments online.

The issue with Raast however, is two-fold. Firstly, the State Bank has only allowed banks to use it in the first phase, though payments services providers (PSPs) are expected to eventually have access to it as well. Secondly, the central bank has currently only enable one feature on it: one-to-many payments, where one bank account is the origin of payments going to several other bank accounts (like, for example, the Ehsaas program, which is what it is built to support at the moment.)

Of course, both of these are temporary hurdles. The State Bank will make Raast more available to fintech players, and it will enable more types of transactions over the next two years. Raast also has the added advantage of being significantly cheaper than other alternatives. While the 1Link system can cost as much as 1.5% of the total transaction value, sources tell Profit that the State Bank will likely price Raast at considerably lower than that, and possibly even as low as a flat one rupee per transaction.

The payments fintech wave

Add in the yearning among Pakistani consumers for online transactions with the State Bank taking it upon itself to build a unified payments infrastructure that is low-cost, instantaneous, and finally built for the internet age, and one can see why the fintech space in Pakistan is heating up and why venture capitalists appear to be landing in Pakistan with dump trucks of funding for startups that are trying to solve the payments pain points for Pakistani consumers.

The list of impressive names and resumes in this space is quite long. The most recent entry is of course the eponymous Tag, named after its founder Talal Ahmed Gondal. Tag has only just been accepted to the summer 2021 batch of the San Francisco-based startup incubator YCombinator, and it has already raised a $5.5 million pre-seed round of funding from several marquee investors. Tag is currently an electronic money institution (EMI), but plans to eventually apply for a digital banking license.

Then there is Safepay, which bills itself as the Stripe of Pakistan and has managed to raise a seven-figure amount from several investors including Stripe itself. (For those unfamiliar, the US-based Stripe is the world’s largest payments startup that is still private.)

Finja, another fintech startup, has thus far managed to raise $15.65 million in disclosed funding from several investors, both local and foreign. Its local investors include a debt investment from Habib Bank Ltd.

We could keep listing more startups with astonishingly high levels of funding (by Pakistani standards), but you get the idea. This is a hot space, and the VCs are chasing after whoever they think will build a winning platform.

Regardless of whether one startup succeeds or many of them do, one thing is clear: the Pakistani consumer – and Pakistani businesses – are likely to be able to find it significantly easier to do business online, which is especially welcome at a time when more and more of us are becoming comfortable using the internet for commercial transactions and would like the convenience of having our payments being online as well.

For all the talk of Pakistanis being old-fashioned and cash-obsessed, the data suggests the opposite: they are hungry for technological change. If only the industry can keep pace.

The main problem in the long run for all non cash platforms (or EMIs) is that of determining an optimum transaction cost i.e. what will the price customers are willing to pay for a transaction. I have been using easy pasa for some time a few months ago they had no limit on the amount being transferred to any bank account suddenly they changed it and caped it at Rs. 5,000 which is such a small amount that one cannot use it for any business purpose however small it may be, further there franchises are not only charging on the withdrawal of the money but also at the time of depositing. Access to your own money should be basic right why to pay for it.

Farooq, another excellent article. Informative and useful. Just to correct one point, HBL make an equity investment into Finja, PKR equivalent of $ 1.15 m, as part of Round Series A-1 of $10.1m. An additional debt investment may be considered in the future.

Also, a clarification: By “internet-based payments” you mean mobile app-based payments, card-based e-commerce, desktop browser-based internet banking, and online B2B transfers? And non-Internet would be cash, cheques/PO, POS and ATM?

And in Payment Service Provider, you include PSP, PSO, and EMI?

Thanks

Yusuf