By the end of 2020, while the world watched as Covid-19 rapidly changed everything with little regard for traditional notions of success, some Pakistani startups had a lot to celebrate. The global pandemic seemed to be exactly the kind of push that they needed to convince customers to move to online platforms and to convince them of the benefits of such operations.

Among the startups hailing basking in success were the ones that had gotten involved in online grocery shopping. Covid-19 meant that people no longer wanted to do the monthly trip down to the supermarket. But even as these startups celebrated a large number of people beginning to use their platforms frequently and trusting their business model, they will have had one eye on Hum Mart – one of the early entrants into the game.

A subsidiary of HUM television, Hum Mart makes an interesting case study. It started operating in 2018 with aplomb, offering discounts and deals aplenty. It had the backing of a large company and its name was well recognised. Yet somehow, within two years, they had to close down in what the management is calling a ‘temporary’ shut down so that they can revamp.

Eyes and ears in the industry are calling the fall of Hum Mart an introspection point for the grocery delivery industry and if it holds any future in Pakistan. If a player like Hum Mart, which has the financial backing of a known media company, could crumble, how can the others survive?

Let’s clear the air here about Hum Mart. There have been reports of mismanagement and excessive theft, with a source telling Profit that there have been instances of riders going out with goods worth Rs1,500 when the orders would be of Rs1,000 worth. A source in the management of Hum Mart, denying that there was any mismanagement while running operations of the company, attributed the shutting down of business to a risk factor that Hum Mart did not even slightly perceive could become an existential threat. The feud between the siblings, Jehangir Siddiqui, the retired investment banker and founder of JS Group, and Sultana Siddiqui, the force behind Hum Network Limited that resulted in the hostile takeover of Hum Network Limited fundamentally affected the operations of Hum Mart

Collateral Damage

If you go to the Hum Mart website today, there will be nothing but banners and announcements telling you how Hum Mart is on hiatus, but is about to come back bigger and better. As a consumer, you might wonder what happened to Hum Mart that it had to shut down first to come back bigger and better. Normally, if a business is growing, it keeps growing, getting bigger and better. Only if a company is not doing well, it would shut down and make an attempt at saving face by claiming to be ‘coming back bigger and better’, leaving everyone up in the air whether the business would be back or not.

In the case of Hum Mart, things, however, add up.

“A VC offered Hum Mart money in 2019, which the company did not take, even though the company was losing money and had burnt all of its equity. The rationale was that if Hum Network, which owns 70% of Hum Mart, was ready to support Hum Mart, it did not make sense to raise venture money and lose shareholding to a third party,” says a source.

The approval for the loan, disbursed in quarterly installments, came from the board of directors of Hum Network Limited. As testament from two sources, the company was on a growth trajectory since its operations. While there was growth, it was coming on the back of losses, which a source said were planned for and come as part and parcel with growth in eCommerce.

In August 2020, however, the company went down the tubes in the aftermath of the dispute between the two parties, JS and Sultana Siddiqui, in which JS thrusted a hostile takeover of Hum Network Limited. Court cases that ensued resulted in the dissolution of the board of directors at Hum Network. It was the board of the company that Jahangir Siddiqui wanted to dominate. However, the consequence was that the loans that were Hum Mart’s lifeline to grow, stopped. And in the absence of venture capital money, the going was simply getting tough. According to sources, Hum Mart only had approval for loan until September 2020.

Hum Mart was incurring losses. Then the funds to operate stopped because of the feud at the parent company. In this backdrop, in the beginning of April this year, the company planned to temporarily shut down the business until a clear verdict from the court was announced.

“The worst part was that because of the cases at court, venture capital firms refused to put any money in for as long as there were any legal complications. VCs simply won’t involve themselves in this mess until a court verdict is reached,” said a source.

While there is still considerable ambiguity, according to sources, some progress has been made with court cases and the company has managed to secure funds from an individual investor. “Hopefully, the court will resolve matters in the coming few months and the company will be launching again by Eid,” adds the source.

While the company claims on its website it will be coming back by Eid, there is no surety if it will actually make a comeback by that time. Court cases can linger on and while the timeline is uncertain, sources claim that Hum Mart is poised to come back. It is even going to come in with a different business model, owing to its financial constraints. Hum Mart launched in Karachi and has since remained there until the recent bust in operations. Its comeback, however, as planned, is going to be with Hum Mart launching in a few cities simultaneously. Where in Karachi Hum Mart had a central warehouse from where it would do deliveries, the new model will include third party fulfillment partnerships under which customers would be placing orders on the Hum Mart website and the fulfillment partner, which will also keep the inventory, will deliver the order.

Since the company would not be investing in its own warehouses in different cities, its expenditure would be limited, which will help it launch in other cities simultaneously with its fulfilment partners.

For a loss making startup that was hit so badly that it had to shelve operations completely, its planning to return only goes on to speak about the potential of grocery delivery in Pakistan. After all, if it did not have potential, it would have been better to shut down and the saving grace here would have been the feud that led to Hum Mart’s demise instead of the business doing badly in a potentially bad market.

But as it turns out, the market is not bad at all. Hum Network annual reports from the time Hum Mart was launched note that launching Hum Mart could potentially be a profitable business and that the company was striving for growth in this segment. Sources also say that the company had an upwards growth trajectory till the fiasco but the startup is very much up to stay in the game.

Other startups have also entered into the space while older ones are apparently thriving. So what exactly makes eGrocery so interesting for these startups?

The state of eGroceries in Pakistan

Startups, for all their ingenuity and good qualities, are all based on one business or the other. Most of them in Pakistan are trying to turn outdated processes digital and improve them through technology. So a lot of the time, they like to take credit for things they have no hand in. Currently, the important names in the online grocery space in Pakistan include the likes of Airlift Grocer, Grocer App, Panda Mart, October, Hum Mart, Naheed, Carrefour, Metro, Al Fatah, Mandi Express, D fresh, and D Mart amongst many more. Some of these, like Airlift, had to adapt during the pandemic and shift to online grocery stores to survive. Others, like Al Fatah and Metro, have been in the groceries business for a very long time and it was only a matter of time before they moved towards the online space as well.

All of these companies will try to sell you the idea that it was their bright idea to take grocery shopping online. The reality is that online groceries in Pakistan have existed for a while. Chain stores with large presences have been delivering groceries and had websites for a while. The idea had not exactly caught on before the pandemic, but it was also not a complete bust. In fact, there is a culture in cities like Lahore and Karachi of local kiryana stores taking orders on the phone and delivering directly to houses in the area, and you have a population willing to shop online.

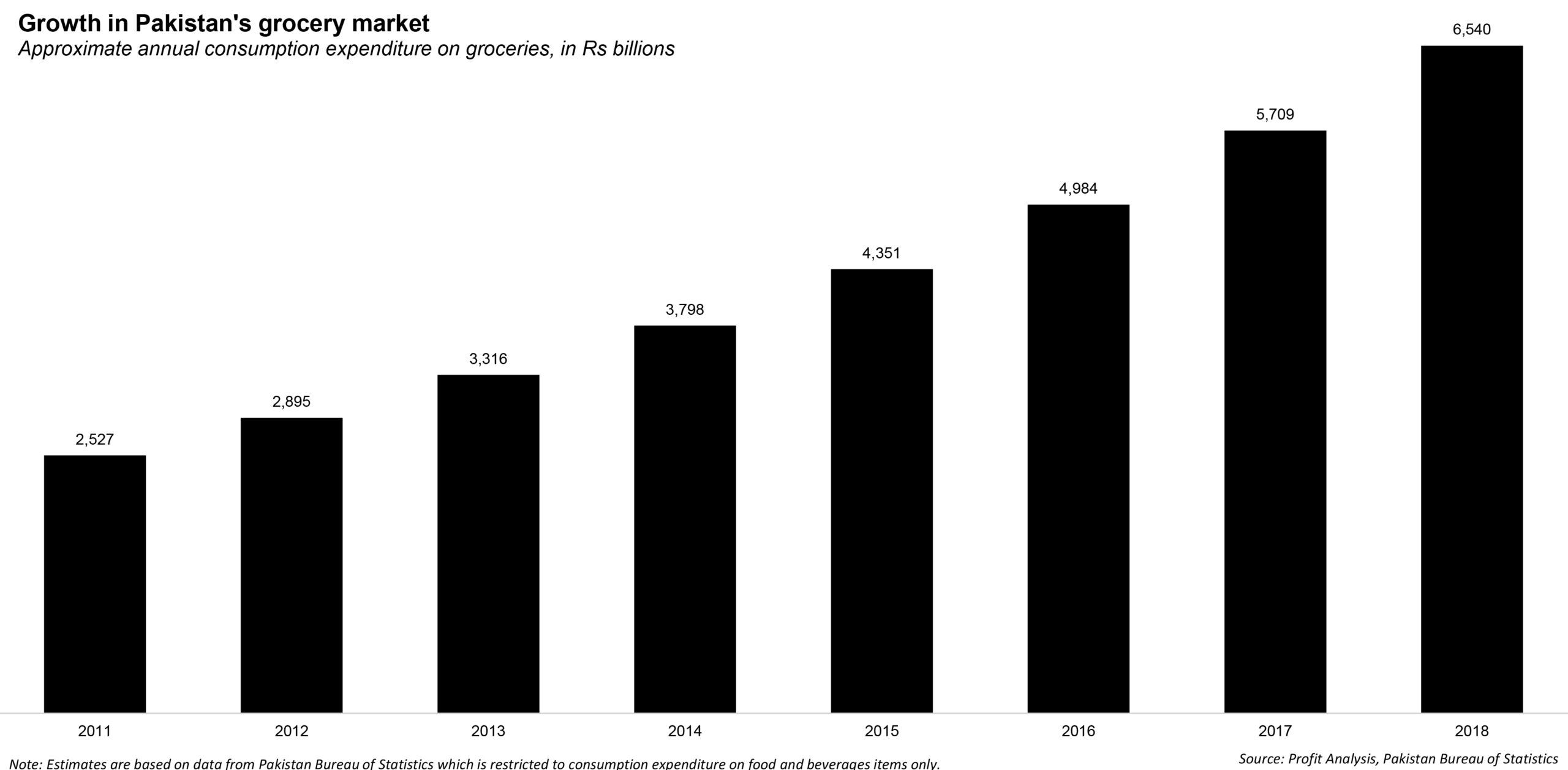

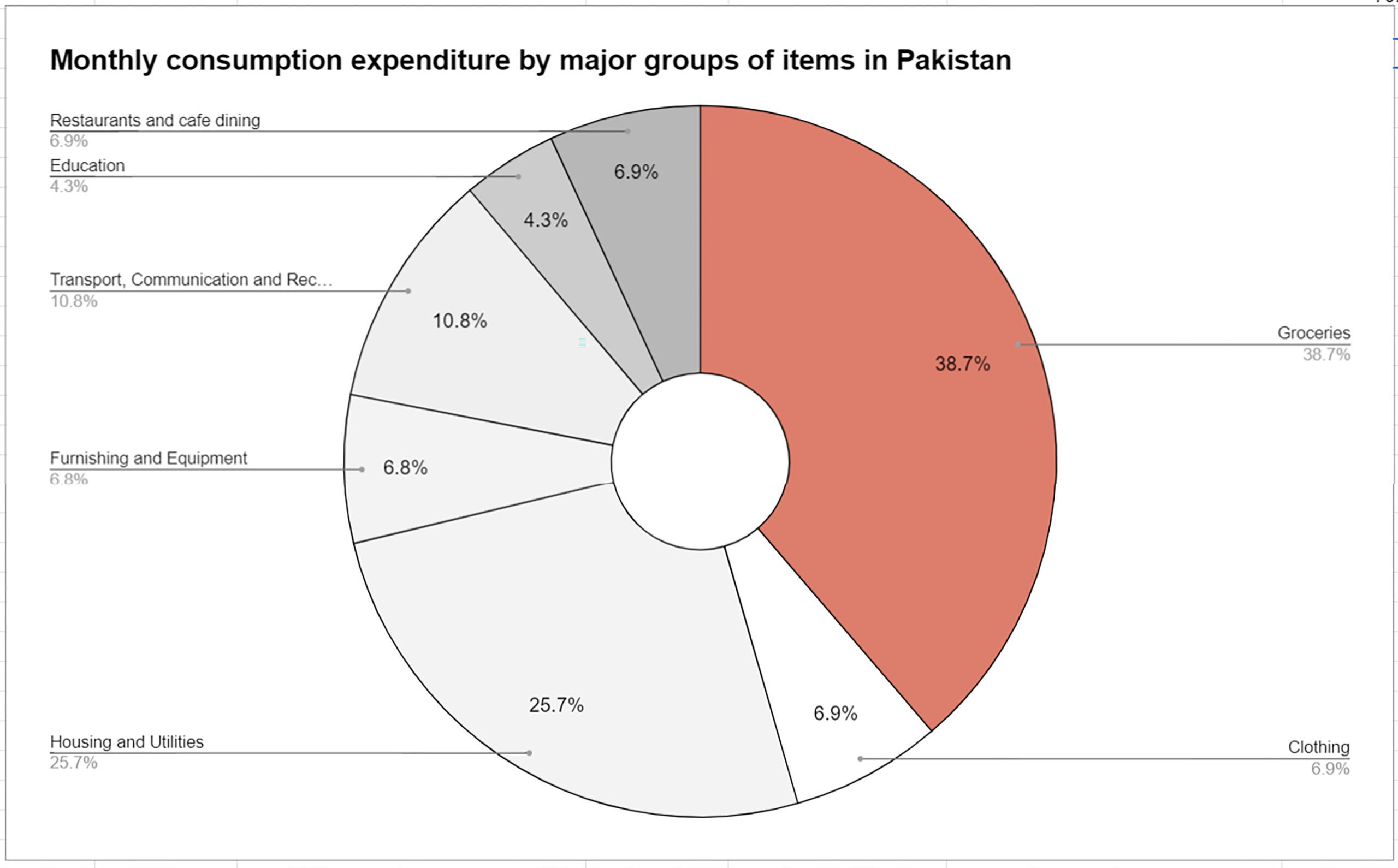

Pakistan’s retail grocery market is the single biggest component of total consumer spending. According to Profit’s analysis of Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) and Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), consumer spending on groceries was approximately Rs6,540 billion in Pakistan, approximately 38.7% of total consumer spending.

This market has been growing at a relatively average rate of 12.7% per year between 2002 and 2019, a period during which overall inflation has risen by an average of 8.1% per year.

Both incomes and consumption levels are higher in Lahore than in the country as a whole. Profit’s analysis of PBS data suggests that while the city accounts for 5.4% of the country’s population, it accounts for 6.9% of total grocery spending in the country.

All of the aforementioned players are trying to secure a chunk in the $48 billion pie called groceries. Currently, the pie is dominated by offline retailers, the likes of Metro, Carrefour, Al Fatah, JalalSons and Imtiaz, who have been around for decades. While the pie is dominated by these big players, startups have found themselves some problems in the consumer grocery purchasing cycle that they have jumped in to solve and based on the problems that they are trying to solve, have constituted different models.

To begin with, the generic problems that having an app, a website and a delivery service instantly solve. For instance, the convenience of getting groceries delivered to your home would simply be a blessing for some people and the convenience was visible for some during the pandemic lockdowns. This is why many startups launched during the pandemic while others say they thrived exponentially.

There is always the option of walking round to your nearest general store, thela wala, or mart to buy the product. Most people go with the convenient option as opposed to going all the way to a far off supermarket for such needs. While the nearest option is not the cheapest, it makes up for it in convenience. Similarly, you’ve got online grocery platforms. The prices may not always be able to compete with the prices you got during your monthly grocery haul, but they are able to compete with prices you may find at your nearest store.

One also needs to keep in mind that not all cities around the world, or Pakistan for that matter, are like Karachi where you can find a general store every two streets. That is where the dark store business model actually works best. As for perishability, not all products are easy to transport. Eggs crack, biscuits crumb, juice boxes can get squished and fruits can become bruised. The longer the distance the more likely something could go wrong with your order. While there has been an increase in the demand for online grocery shopping considering the ease, convenience, and more importantly the massive customer acquisition costs that businesses are running through; no one really knows how long this will last.

Then grocery purchasing could be segmented into different categories based on types of groceries different types of consumers like to buy and that could differentiate the startups that we have in the market.

For instance, all the millennials out there who perhaps don’t know what the difference between cooking oil and ghee is, like to have their pack of Lays or a bottle of Nutella or ice-cream, without having to go out to buy it. They would want it fancy, they would want it now. Sometimes they wouldn’t want to go out to buy it, sometimes they would want it at times when shops would be closed. These millennials form a market that wants products, low value items, purchased repeatedly, which could be a lost demand if let’s say a shop is closed at night. Here, startups like pandamart will deliver it to you late at night.

In the same category are products like fruits and vegetables, that are consumed in a short period of time and the purchase is repeated every two or three days. This is the segment that companies like pandamart, Airlift Grocer, Cheetay target where products have to be delivered immediately because of the instant gratification nature or urgent need of these products. Naturally, the order value is small and the delivery has to be swift.

This is why pandmart offers a 15 minute delivery service and is laying out a network of dark stores, scattered in neighborhoods, with cheap rentals, that optimises its costs, yet enables quick deliveries. Cheetay is following a similar model of setting up dark stores for swift deliveries and has 3 dark stores at the moment, compared to 30 that pandamart has.

Then there is the consumer segment that likes to do grocery shopping for the entire month. For example, the family heads, old in age, are habitual of doing entire groceries biweekly or monthly which include big value items like flour bags, cooking oil, shampoos and stuff. Startups serving this segment are GrocerApp, and the aforementioned Hum Mart. Their logistics infrastructure is also based on fulfilling demand from this segment. GrocerApp for instance has customised rickshaws that can carry big value items to deliver in one go. Their delivery times are also in hours rather than in minutes.

Then are the problems that come simply along with the grocery business. The problems of unauthentic, counterfeit products.

“There is no standardised experience in products which we saw as a major gap. No single retail chain is big enough to have a presence all over Pakistan to ensure standardised products,” says Nauman Sikandar, CEO at pandamart.

This is what it all sums up to: there are counterfeit products in the market that people want to avoid, there are different demand drivers for different products, different consumer behaviours, add the convenience of getting these products delivered helped by the pandemic, you have startups like GrocerApp, pandamart and others that have made their presence felt, though they are yet to make a serious dent in the grocery space.

It’s only starting

To be clear, when we earlier mentioned the two different categories of products and consumers that it is delivered to, that is low value items purchased repeatedly and high value items purchased with a gap, did not mean these startups are restricted to those models only. That is only what they have started off with, based on strength and strategy.

For instance, pandamart, which is an offshoot of the bigger foodpanda that has a vast network of riders, running in thousands, uses the same fleet for grocery deliveries that predominantly uses bikes to make these deliveries. The fleet inherently has a capacity limitation that a bike can not deliver big grocery orders in one go and, therefore, started with smaller items that it could easily deliver. Add to that pandamart used its strength in data that it has from the foodpanda business to analyse consumer spend in neighborhoods to strategically place dark stores that enable deliveries in 15 minutes through the bike riders.

Conversely GrocerApp, which targets high value grocery items, has a central warehouse from where it dispatches the items for deliveries through rickshaws, though it also has bikes in its fleet to deliver low value items.

Essentially, these startups are targeting different basket sizes for their business that suits them the most according to their operations. According to industry experts, the average basket size for pandamart, Cheetay and Airlift which are all initially targeting a similar set of consumers, is between Rs600 to 700. Whereas for GrocerApp, the average basket size can go as high as Rs2,000 or above.

Similarly, Daraz is also into eGrocery and is targeting a smaller basket size at the moment. “Everyone right now is trying to get to that sweet spot of having an optimum basket size. At different scales, that size is going to be different,” says Ahmad Saeed, CEO at GrocerApp.

Smaller or bigger basket size does not mean it is going to stay that way because margin wise, both make sense. The grocery retail margins, gross, vary for different categories of products, but on average add up to 9-10%. So if pandamart makes a delivery for an average basket size of Rs650, at 10%, that is Rs65 in revenue. Conversely, GrocerApp’s single delivery for a basket size of Rs2,000 would yield Rs200 in revenue. The difference is stark, but for the lost revenue due to basket size, pandamart can make up for the higher number of deliveries it does as compared to GrocerApp.

But having a bigger basket size has its benefits. It brings down the average delivery cost significantly. Which is why dark stores optimise cost for pandamart. These dark stores are facadeless, have cheap rentals and the rider does not have to go to a central warehouse which would increase delivery cost for low ticket items.

“We have about 30 dark stores in Pakistan. From a logistics point of view, we have opened those at places that are prime, where rentals are less and consequently margins are fair,” says Nauman Sikandar.

Cost optimisation is also where being a tech company helps. Since these startups have data of product purchases, they can optimise purchases and even manage inventory for swift operations and deliveries that help scale.

“The key is to structure a model that keeps your cost very very low. And the way you do that is by having a lot of scale. As your order volume increases, your unit cost is going to decrease,” says Usman Gul, CEO of Airlift Express.

According to an industry expert, different models are just a way of getting in the game. “Everyone is trying to be the go-to grocery service. Some are starting with instant gratification products model, others are targeting major grocery items. The principle at the end of the day is to attract consumers to the platform enough for them to eventually start ordering different value products as well. If GrocerApp grows big enough, people will impulsively start ordering smaller products eventually. Conversely, if pandamart keeps going with this model, eventually people will say if I am ordering ice creams from here, why don’t I order oil and rice too. Same is the case with other startups,” says the expert.

This goes on to validate that because startups want to gain maximum traction, they plan to launch their own white label products, which, if a hit, would make the respective platform more wanted. Cheetay has, in fact, launched its own brand of milk, called Sahar milk. Having your own product is great that will certainly add to the traction and revenue for the platform and if successful, people who would want to order the brand of milk from Cheetay would also start impulsively buying rice, wheat flour or other grocery items, further increasing the traction of the platform.

Is it profitable?

“At the end of the day, eCommerce is an expensive business. It is an expensive game that ends up tying your cash flows to a large degree. Secondly, on the grocery side, you really need to have a product that you have on your own. Oftentimes, the working capital gets tied up for a long time and it becomes challenging,” says Ehsan Saya, managing director at Daraz.

When the news of Hum Mart shutting down started making rounds, the immediate assumption in many people’s heads was that the business was perhaps doing badly. That it could not generate significant revenue or could not see generating profits, which is why it went bust. That the company tied cash into capex and could not get enough traction.

As earlier mentioned, the problem was entirely different with Hum Mart, but had the problem not arisen, could Hum Mart have become a profitable business? After all, sources revealed that Hum Mart was growing while sustaining losses that were planned for four years. Though it was not disclosed if profitability would have come after four years or not. The question also is that on a broader level, can eGrocery become a profitable business, because other startups in the space are also sustaining losses.

From candid admissions of startup founders, pandamart is not profitable, GrocerApp is not, Airlift is not and Hum Mart was not. At the same time, however, the founders make haughty claims that they can become profitable whenever they want to. It’s just that they don’t want to right now for the sake of expansion.

For example, GrocerApp says they will be turning profitable in Lahore this year but they have expansion plans because of which they would divert the profits to loss making operations in other cities to sustain them.

eGrocery startups primarily see the likes of Metro, Carrefour and Al Fatah as the mammoths they have to compete with. Grocery space is very big and startups are really small. All of them are so small and the space is so big that they can all coexist for the time being.

Startups’ primary income is the margin that they earn on selling grocery products. Then they have delivery fees, which was earlier waived to get traction for the platform but pandamart and GrocerApp have started charging nominal fees for covering certain portions of costs. Then there are negotiations with manufacturers for higher margins, that companies like Carrefour and Metro are able to secure because they are simply very big and generate massive volumes for manufacturers.

“Manufacturers would sell to normal retailers at trade price. To Metro and Carrefour, manufacturers sell at trade price minus one, two or even three per cent. The startups will try to negotiate similar deals with manufacturers which offer them greater margins and that is going to come with high volumes. Essentially, these startups would also be cutting out the distributors and get distributor margins for themselves if they are able to grow big enough like Metro and Carrefour that manufacturers don’t mind dealing with them directly,” says the sector expert.

The deal here is that the startups are sustaining losses deliberately to expand countrywide, grow big in volumes so that manufacturers give you the margins that Carrefour and Metro get. For context, Carrefour and Metro’s gross margins are 15-20% compared to 10% for startups and normal retailers.

“Hyper fulfilment in our model is coming at a higher cost and we are going to the manufacturing companies and asking them that since we are generating value and demand that otherwise would have been lost, for that, you give us additional margins. That is still conceptional but that is going to be the case moving forward,” confirms Nauman.

“Big manufacturers also have massive marketing budgets. Metro, Carrefour get hefty sums from these manufacturers and we receive the same as well for marketing their products on our digital channels,” says Ahmad Saeed.

At the end of the day, startups, when they are operating in a country like Pakistan where people are not used to ordering stuff via mobile or website applications, some of the spend is always going to go towards discounts to drive growth. The same is happening with grocery deliveries too. They offer discounts, which constricts their margins, which means losses and further funds to sustain if you plan to grow at the same time.

So in the endgame, the startup that is able to constantly fund its operations is going to survive and make profits. And by far, pandamart is the strongest in the game right now. It has a parallel business that has dominated the food delivery space, and it has the backing of the Germany-based delivery giant Delivery Hero. Other startups are VC funded like GrocerApp that raised $5..3 million this year, Airlift raised $10 million last year and another less known grocery startup, 24seven.pk is also in the process of raising new funds.

In the endgame, the strategy of these startups will also matter. Those not seeking an exit are going to be in the game for the longer run, most likely foodpanda. Others who have planned an exit will simply get acquired by an existing player. Some that have already perished, reportedly Karachi-based QNE has shut shop, and some more will perish in keeping up with the eCommerce game. At the end, we might only see a few big players, perhaps as many in numbers as the big physical retail giants like Carrefour and Metro, because as Ahmad Saeed tells us, no one player can be big enough to cover the entire grocery segment alone.