If you have been a business journalist for a while, then you will relate to this. And if you are a reader of financial news, you will also recognise the pattern. Any time a business, or an industry association is interviewed – no matter what that industry is – they will always say the same thing.

Relief. They want relief in some form or another. They want relief in the budget, they want stimulus packages, they do not want to be taxed, and they do not want to be questioned. And this princely treatment they both expect and demand, and when they do not get it, they whine about it and they whine loudly. So the reader will understand that anytime we hear complaints like this, we are less than receptive to them.

Still, we tolerate it because old industries like textiles, agriculture, steel, and others have worked that way for a while and are stuck in their ways. What is surprising is when newer industries that we expect to behave differently engage in the same sort of behaviour. So when the eCommerce industry went up in arms with a systematic campaign against the budget for the fiscal year 2021-22, it had everyone surprised.

On this occasion, however, the campaign may have been justified. You see, this was not complaining or asking for handouts, this was an issue of definitions. In the most recent budget, the government decided to include ‘online marketplaces’ in the category of Tier-1 Retailers, effectively burdening the marketplaces with the responsibility of reporting sales tax for their sellers.

Online marketplaces in Pakistan are new, and eCommerce has only just found its true wings in the past couple of years, so at this point it is very important (fiscally speaking) to define what these platforms are exactly and how they should be treated by the tax authorities. But the new definition prompted the question: why should eCommerce businesses take on taxation responsibilities, and help formalise the informal economy at their own cost, when there are government departments to do that?

So, the move jolted companies like Daraz, and they hustled to get the clause of designating online marketplaces as Tier-1 Retailers removed from the budget before it was passed. They were successful.

On Tuesday, June 30, the budget was passed without the said clause. Instead, however, the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) managed to get a tax imposed: marketplaces like Daraz are now required to withhold 2.5% of the amount of their unregistered sellers as withholding tax (WHT), as well as from registered sellers that are not filers. According to FBR officials, the rate of WHT is 2.5% whereas online marketplace Daraz contends that the rate was 2%. Since the rate from FBR is 2.5%, we will stick to considering that as the rate that is officially effective.

In the earlier plan that the government had to declare online marketplaces as retailers, Daraz would have to report the numbers. Under the new provisions, they still have to report taxation to the government, but only have to deduct 2.5% as WHT from sellers. And that, of course, is critical to the sellers on platforms like Daraz, PriceOye, Telemart, Homeshopping and others.

The difference in tax percentages fundamentally affects online marketplaces because the number of unregistered sellers on these platforms are over and above the number of registered sellers on these marketplaces. In a recent interview, a high-ranking official from the FBR disclosed that 93% of the sellers on Daraz were unregistered.

There are four realities to be aware of to understand the implications of these new rules. The first are the perpetual efforts of unregistered businesses, offline sellers as well as online sellers on eCommerce platforms, to remain out of the tax net. The second is the eternal desire of the tax authorities to bring unregistered businesses into the tax net. The third are online marketplaces that bear the brunt of the war between the revenue authorities and these sellers, trying to strike a balance. The fourth, perhaps most important reality is that eCommerce businesses are in losses and their business model is under stress.

There’s a lot to unpack here and we’ll start with some basics of tax avoidance.

Taxation hacks

If you are a business registered with the revenue authorities, chances are that you might have placed an order for an electronic product with an online marketplace. For the sake of understanding, let’s say that you are a business looking to purchase an iPad for use at your office and decide to get that online because that saves you the convenience of not going out to buy one. Now, any business registered with the revenue authorities is required to withhold 4.5% of the amount if the value of the purchase goes beyond Rs50,000 in a calendar year.

As a registered business, you have to withhold an amount from the sale price that you get on an online marketplace and submit it to the FBR. The 4.5% that is reported to the FBR can be claimed by the marketplace or a seller on the marketplace as tax paid on the income and will only have to pay the remaining percentage of the income tax at the end of the year. The 4.5% was already paid and reported to the FBR on behalf of the marketplace or the seller by the business while purchasing the iPad.

The problem is that if the marketplace or the seller is unregistered and already out of the tax net, it is going to hike the price given on the website for the iPad by 4.5%. Why? Because unregistered marketplaces, if they are selling the iPad to you directly, or sellers on a marketplace if they are unregistered and selling it to you through the marketplace, don’t want to pay any income tax. Since they do not want to pay any income tax, they wouldn’t want the 4.5% to be deducted by the business that has been obligated to deduct and report. This is simply a lost income for unregistered sellers or marketplaces. The consequence is that the business ends up buying that iPhone at a higher price, up by the percentage amount of the withholding tax.

From the market research done by Profit, three of the known online marketplaces, Telemart, Homeshopping.pk and Tejar, added WHT on top of the price of various electronic products listed on the website, during price inquiries as a business.

Let’s also lay out a distinction here: there are online marketplaces that are retailers themselves, that buy and hold inventory, and sell it to consumers like a retailer. An eCommerce player that follows this model is Daraz. There are certain products that Daraz keeps as its inventory and if a consumer buys that product, Daraz charges the GST on to the consumer, just like any other offline retailer that is registered. Daraz pays the taxes on its income earned through this segment of the business. Then Daraz acts as a middleman, online, opening its online platform to individual sellers to find buyers for their products, does marketing for them and when the sale is made, deducts a predetermined commission before reimbursing the remaining transaction amount to the seller. And as mentioned above, companies like Daraz pay a service tax on this commission to the government from this revenue stream as well.

This distinction could open up avenues for tax evasion for companies that follow both models and here it gets trickier. The platform could actually be a retailer posing as a marketplace. For instance, you could be purchasing an iPad that Daraz might actually be selling as a retailer and in that case, it’s Daraz that is adding the WHT on top to avoid taxes and not the seller. This can happen with marketplaces that claim they are marketplaces and retailers, active taxpayers, but are not transparent about who the seller is.

But in the case of Daraz at least, most of the time you would see the name of the seller who is selling a product to you on the website. It would be a third party seller most of the time because only 10-15% of Daraz’s business comes from retail and 85-90% comes from the marketplace.

Daraz’s retail is mostly restricted to Daraz Select, which is its private label brand. Besides, some brands, mostly the FMCG brands as Daraz tells Profit, sell their inventory to Daraz which then stocks that in its warehouses.

“Daraz buys that inventory and fulfills that under the banner of ‘fulfilled by Daraz’,” Daraz told Profit in a statement. For the inventory that Daraz sells itself, no WHT was added on top of the listed price on the website for these products during our price inquiries. Whereas for products of other sellers, a representative from Daraz said that it would be up to the seller if he adds WHT on top or not.

Daraz’s transparency gives it an edge over others. For instance, Telemart also claims it is a marketplace, has an option on the website to register sellers, but does not name sellers with the products it lists like Daraz does. On the other hand, Homeshopping.pk calls itself a marketplace but there is no option on their website to register as a seller and neither does the website list vendor names with the products. Its most trickier in the case of Homeshopping.pk to verify if it is the platform selling the product itself or selling the product of a third party seller.

An official at Homeshopping.pk says that they do not buy inventory from sellers, or keep it, and the transaction process looks something like this if you are purchasing as a business: sellers would give Homeshopping a fixed price for the product that they list on the website that the buyer can initially see; customer would put an inquiry for the product; the platform would send a quotation to the customer, approved by the seller, which might or might not have WHT added on top of the listed price; the buyer places the order and the platform would pick the product from the seller, fulfill it at its centres and deliver it to the customer; the payment is collected and the platform deducts its commission on the transaction and pays the remaining amount to the seller.

Nowhere in the transaction is Homeshopping buying the product from the seller or selling it to the customer means that the evasion comes from the seller, or that is apparently what it looks like.

Some of the prominent names in the eCommerce industry, like Lahore-based Shophive, are not marketplaces. If you order a mobile phone on Shophive, it will not be from a third party seller that Shophive would be connecting you with through its platform. It would be selling that phone to you, as Shophive that bought the phone from the seller first and held it, before selling it to you. Which means that Shophive is obligated to charge the consumer the government mandated GST percentage, and if a business is buying, it should be able withhold a percentage of the WHT transparently, without having to see the price of the product going up by the WHT percentage. That is not the case with Shophive, however. It does not charge GST to its consumers, deals in cash and evades withholding tax deductions by businesses. Same is the case with Tejar.pk. It adds WHT on top of the product price to evade taxes.

Here’s a guiding principle: if someone is evading taxes (like by adding WHT on top of the price), chances are that he is hiding his income in totality and not paying any taxes. And if he is reporting his income, he is most likely underreporting it. It is the e Commerce players like Shophive and Tejar.pk that, because they do not bear the burden of taxes, are most likely profitable and because they are profitable should be taxed more.

While there is little transparency with some eCommerce players as to who is the actual seller to identify if the eCommerce player evades itself or the seller that does it, there is admission of the fact that tax evasion happens. Marketplaces acknowledge the practice of jacking the price by percentage of WHT, but say that it happens with a very small percentage of transactions as sales to consumers are much higher compared to sales to businesses.

As Telemart, for example, tells Profit, only 1% of their transactions are with businesses where sellers jack up the price and the remaining 99 per cent are with individual consumers. The 1% B2B sales are further diminished if the sellers are registered and don’t mind withholding tax being deducted during the transaction.

“On offline channels as well, if you are a registered business owner and go to a shop that is unregistered, they will increase the price by the percentage of withholding tax. In unofficial channels there is the harmony of prices,” says Adnan Shaffi, CEO at online marketplace PriceOye.

This here reflects the mindset of the unregistered sellers, offline and online. That they want to avoid taxes as much as possible. Different narratives are presented by CEOs as to why unregistered sellers avoid taxes. Some sellers push the narrative of lack of trust in the government, that what they pay in taxes will not come back to them in social services. However, from the versions received from the CEOs, sellers predominantly do not want their income to diminish. And if taxes are forced upon them, in case of selling on online marketplaces, they will simply switch to the vastly undocumented offline channels.

Government objectives

The government wants to impose withholding taxes on sellers to increase their cost of doing business. The idea of such a technique is that paying taxes while being outside of the tax net becomes so expensive that it is cheaper and good for business to be within the tax net. This way, everyone is happy.

Now, the only way to implement this effectively is if the government actually goes after the sellers to begin with. Instead, the FBR found an easy way out of their job. Instead of going out to thousands of sellers itself, through regulatory fiat, it simply held the online marketplaces by the neck and asked them to do it for the FBR.

That is what the categorisation of online marketplaces as Tier-1 Retailers essentially meant: that marketplaces were burdened with collection of 17% GST from sellers and then reporting it to the FBR.

The marketplaces cannot possibly be responsible for the taxation liability of the sellers on their platform, particularly because of the kind of medium that online shopping is.

While the condition was repealed, a 2.5% withholding tax to be collected by the marketplaces was imposed.

One could logically argue that online marketplaces should not have a problem with asking their sellers to pay the general sales tax of 17% to the online marketplaces facilitating their sales and then the marketplace would report these to the revenue authorities. Final reconciliations can be done when sellers file returns. But it turned out to be a big problem mainly because the majority of the sellers selling on online marketplaces are unregistered, who want to stay untaxed. Why they want to stay is already established. But what’s prompting them to stay untaxed is where the beef is. It’s the offline untaxed retail industry.

Consider an example of an unregistered sports equipment seller that sells via a physical retail outlet as well as online through a marketplace. In this example let us say that this platform is Daraz. At their retail store, this seller is selling their equipment tax free. They do not charge the 17% GST on equipment to consumers. The retailer sells in cash, and is able to keep details of their earnings on the down low. The same seller is also able to reach a wide range of customers through Daraz and sells at the same price as through offline retail, and does not charge the usual 17% sales tax to its customers. Sellers have various ways to hide the GST. The most common is to report a price that is inclusive of GST.

The seller enjoys healthy margins because the taxes are not there, and taxes can really add up to the cost of doing business. “There are multiple layers of taxes and eventually it can add up to 30-33% in taxes paid to the government which these sellers consider as lost income,” claims Adnan Shaffi.

Now, consider this. The government pops up one day out of the blue and tells Daraz that they now have to collect GST from their sellers (most of whom are unregistered) on each transaction, and then also log and report this collection to the FBR. Daraz suddenly needs to invest in a tax team, make changes in its web code, run after its sellers, and all despite the fact that they are not a retailer. Once again, platforms like Daraz simply connect buyers with sellers online and facilitate the transaction only. They only earn a commission for facilitating the transaction, and as a platform, pay taxes on the commission earned. As a platform, they do not force sellers to charge a buyer 17% in sales tax on each transaction. Hence in the earlier setting, unregistered sellers would not be charging any GST if they were unregistered.

Now if you mandate the platform to collect taxes on behalf of the government and report it as well, essentially, that tax percentage is an added cost for the unregistered seller. Because he is not paying the same in the offline channels, that is his own physical retail store, his cost of doing business via the marketplace goes up by 17% and he simply has the incentive to revert back to offline channels, or to make up for the lost online revenue stream, would move to unregistered online marketplaces selling like him, or would set up his own Instagram store or sell via Facebook page where he will continue to sell without the burdens of taxes.

In all instances, that is a seller that is no longer on Daraz’s platform. Now it would not have been much of a problem if only a handful of sellers were unregistered. But we are talking about a majority here, over 90% that are unregistered sellers, small in size, selling stuff online from their homes. So if over 90% of the sellers from a marketplace move to their own online channels or offline, a tax as simple as the usual GST can become a threat to the existence of marketplaces. To reiterate here, 2.5% is still a problem, but it is less of a problem than 17% would be.

Marketplaces stuck in the middle

“This (2.5%) is a cost that if an unregistered seller analyses, he would realise that he is getting access to a new market through the online platform that he cannot do it himself. This is a cost which is a good step forward,” says Nauman Sikandar, the CEO of Foodpanda.

Foodpanda is itself a marketplace that connects restaurants for food orders. In turn, it charges commission to the restaurants for the service it provides. Nauman says that they have quite a few restaurants that are unregistered, and this will have a considerable impact on foodpanda.

It all sums up to this: taxing unregistered sellers on marketplaces while keeping the massive offline retail untaxed is not going to help. The government would not be able to gather much because sellers would move online because those channels are still open and that would consequently result in the death of marketplaces.

Registered marketplaces pay their due share of taxes, as imposed on them, from whatever model they follow. Which is why marketplaces argue that asking them to further bear the costs of tax collection and reporting would be penalising them for being registered because unregistered marketplaces would be free from this burden even if imposed.

“Total retail in Pakistan is estimated at around $250 billion. Whereas eCommerce retail is around $1 billion. As a percentage of overall retail, eCommerce is very small. Even if we say it is 1 per cent of the overall retail, even though it is much less, by extension, that also means that only 1 per cent of the unregistered sellers are online compared to 99 per cent that are offline. The government has found it convenient to document only 1 per cent of the unregistered sellers against 99 per cent that are offline,” says Hamza Rauf, CEO at Telemart.

“Online marketplaces are burning money and still paying taxes. Unregistered businesses are earning profits and still not paying taxes,” says Hamza.

The government and the FBR are not completely wrong, however. From industry sources that include a tax lawyer and a CEO of another online marketplace, companies like Daraz and others are better equipped to get the sellers registered. They are already equipped with technology, have the systems to do it because they already are collecting taxes, and because they have all the systems, integrating them with the FBR would not have been much of a problem. On the contrary, to document the sellers individually who are not well-versed in taxes, lack the technology and systems to do it online and integrate with the revenue authorities, and are sometimes even illiterate to do it even themselves, is going to be a colossal challenge.

Perhaps that is why the government stuck with keeping some tax to be collected by the online marketplaces, and that is why the industry did not raise much voice when the government withdrew the 17% GST collection requirement and only mandated collection of 2.5% WHT (withholding tax). The cost of tax collection and reporting is still there, which was earlier decried, goes on to say that the problem really was not collection and reporting, but the percentage of tax imposed on sellers that would have driven them away from online platforms.

Marketplaces do not overtly acknowledge tax percentages as the reason that prompted them to lobby to have the GST withdrawn, but appreciate the lesser percentage as WHT. Officially, they stick to the argument that in principle, asking them to collect taxes is wrong. “Our argument with the FBR was not about more or less tax but on the definition of marketplace. What we were further asserting was that payment of taxes was the responsibility of the sellers for whom we act like agents. We are not in the business of doing tax collection. That is not our primary responsibility. It’s not about being tax collection easy or difficult, it’s just that tax collection is not our primary aim or purpose,” says Ahmad Hassan, chief financial officer at Daraz.

The fledgling state of eCommerce

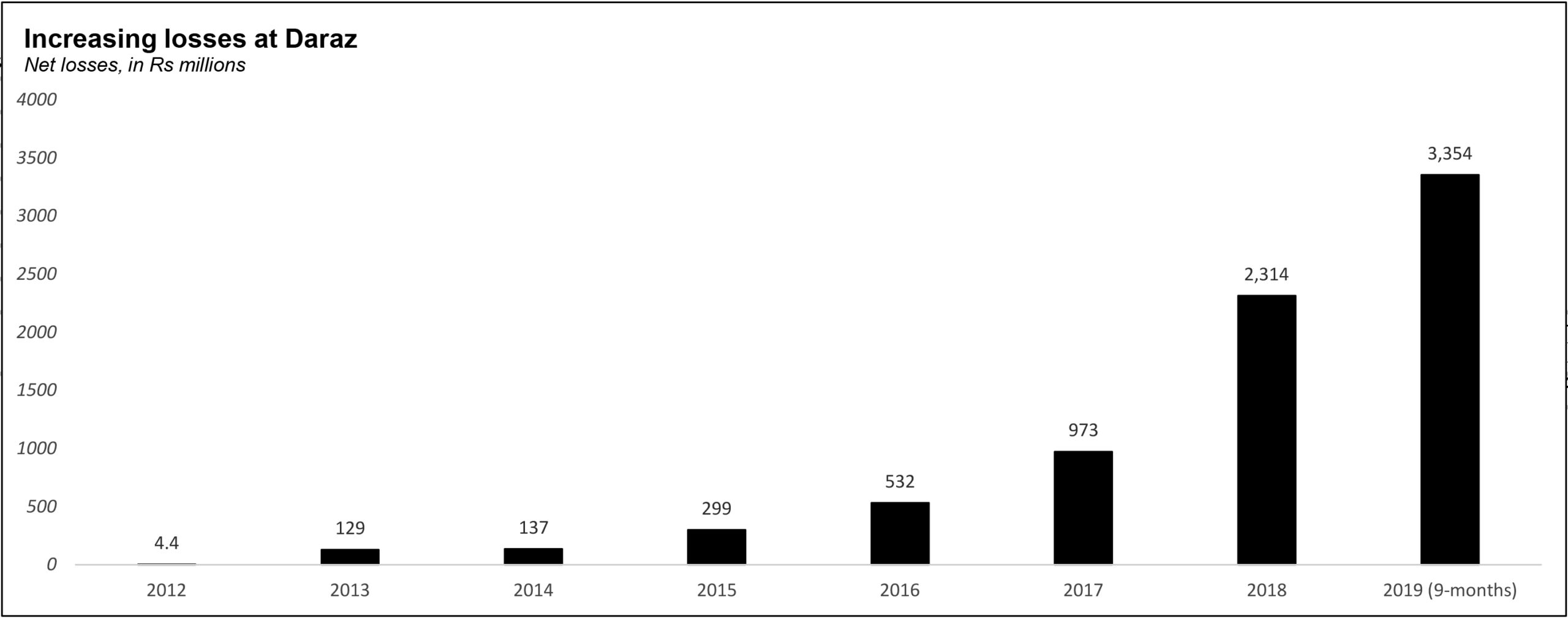

Marketplaces dread sellers leaving their platforms because of taxes. This argument runs in parallel with the fact that marketplaces make losses. All of them. From financials available with Profit, Pakistan’s largest online marketplace, Daraz, has been running losses in billions of rupees. If the largest, and oldest existing marketplace, is running losses, there is a little chance that the newer and smaller ones would be generating profits. And the industry acknowledges that marketplaces run losses right now. We would restrict this argument to registered ones only, however, who are active taxpayers.

Marketplaces are running losses with unregistered sellers on the platform. You forcefully tax the sellers, the loss making marketplace will die. The unique proposition of online shopping is convenience. Yet in Pakistan, eCommerce is mostly discount driven, which typically can only be offered to customers by constraining the profit margins of marketplaces. Only when the model shifts from discounts to convenience will profits emerge.

“Marketplaces are struggling to change behaviour. When scale is reached and behaviour is changed, that is when you can adjust prices,” says Adnan. “For marketplaces, when their volumes increase that of physical retail outlets like Carrefour or Imtiaz, then marketplaces would be able to negotiate better deals with sellers and pass it on to the customer without burning the money of the marketplace,” he added.

Till then, the industry is going to need tax relief to survive. Should the government give tax relief? Well, it already has given some relief by decreasing turnover tax from 0.7% to 0.25%. That needs to be done concomitantly with documenting the offline retail economy. Unless that is done, the industry is going to keep on asking for relief.