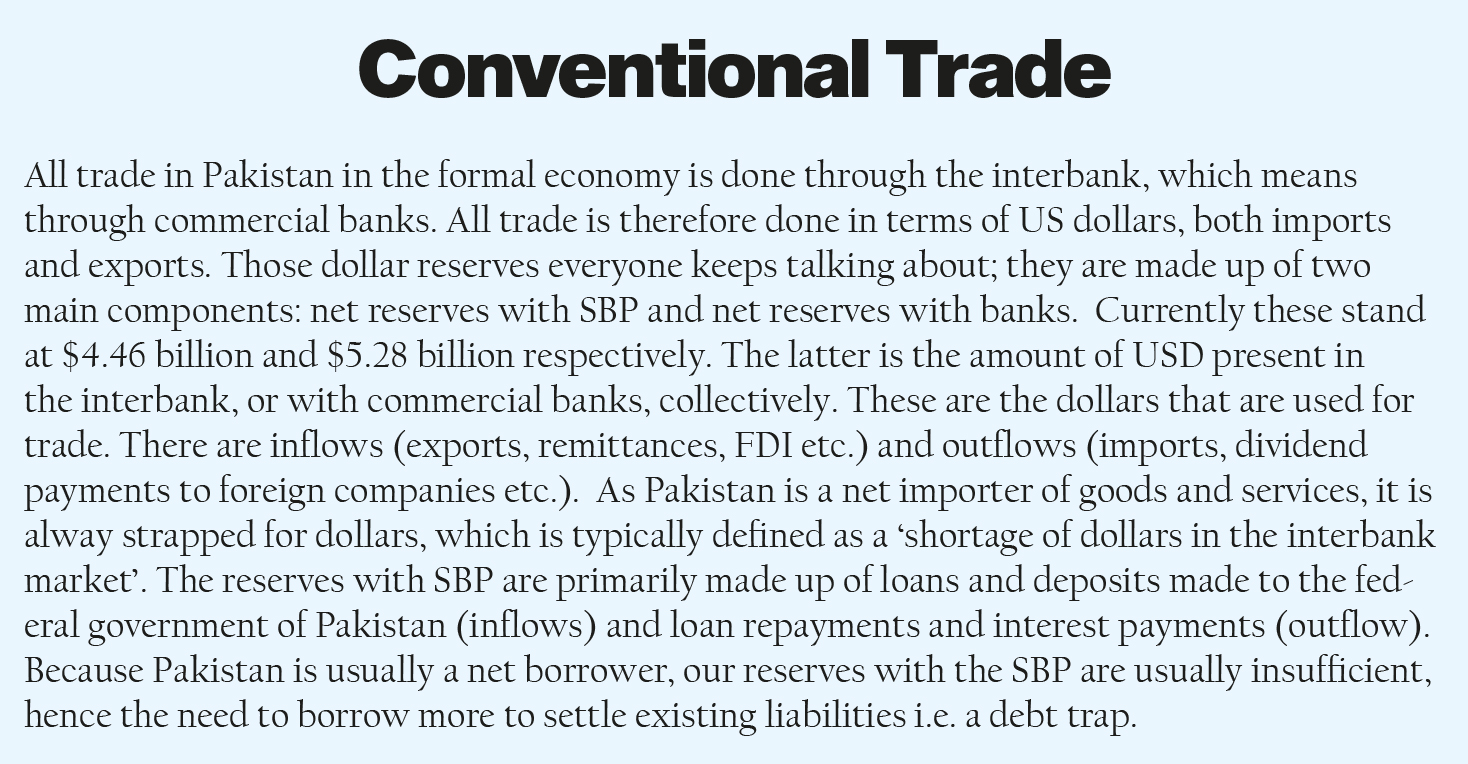

Pakistan remains in a precariously tough economic position. Even with the finalization of the $3 billion IMF deal last week, fundamental problems and underlying weaknesses will remain to evolve into larger issues down the line. We have a crippling balance of payments issue that will only be resolved if somehow we manage to increase exports and FDI, both of which are long term time consuming undertakings that we neither have the time nor structural capacity at the moment to achieve.

The country has cut its trade deficit by a whopping 43% to $27.55 billion in FY 2023, down from a daunting $48.35 billion in FY 2022. This is largely owing to administrative measures such as the restrictions on imports. Imports decreased by 31% to $55.29 billion, from $80.13 billion the previous financial year.

But exports also contracted by nearly 13% to 27.74 billion, from $31.78 billion in FY 2022. Therefore, the drop in imports is how the government has managed to achieve the drop in trade deficit. With all import restrictions removed, a reversal is likely to begin because as things stand, there is no likelihood of an immediate increase in exports.

As such, the government continues to manage matters on a more immediate term, day-to-day basis. Restricting the import of ‘nonessential’ goods is one example (SBP has recently allowed the import of all goods to satisfy the IMF, but restrictions had been in place for close to a year prior).

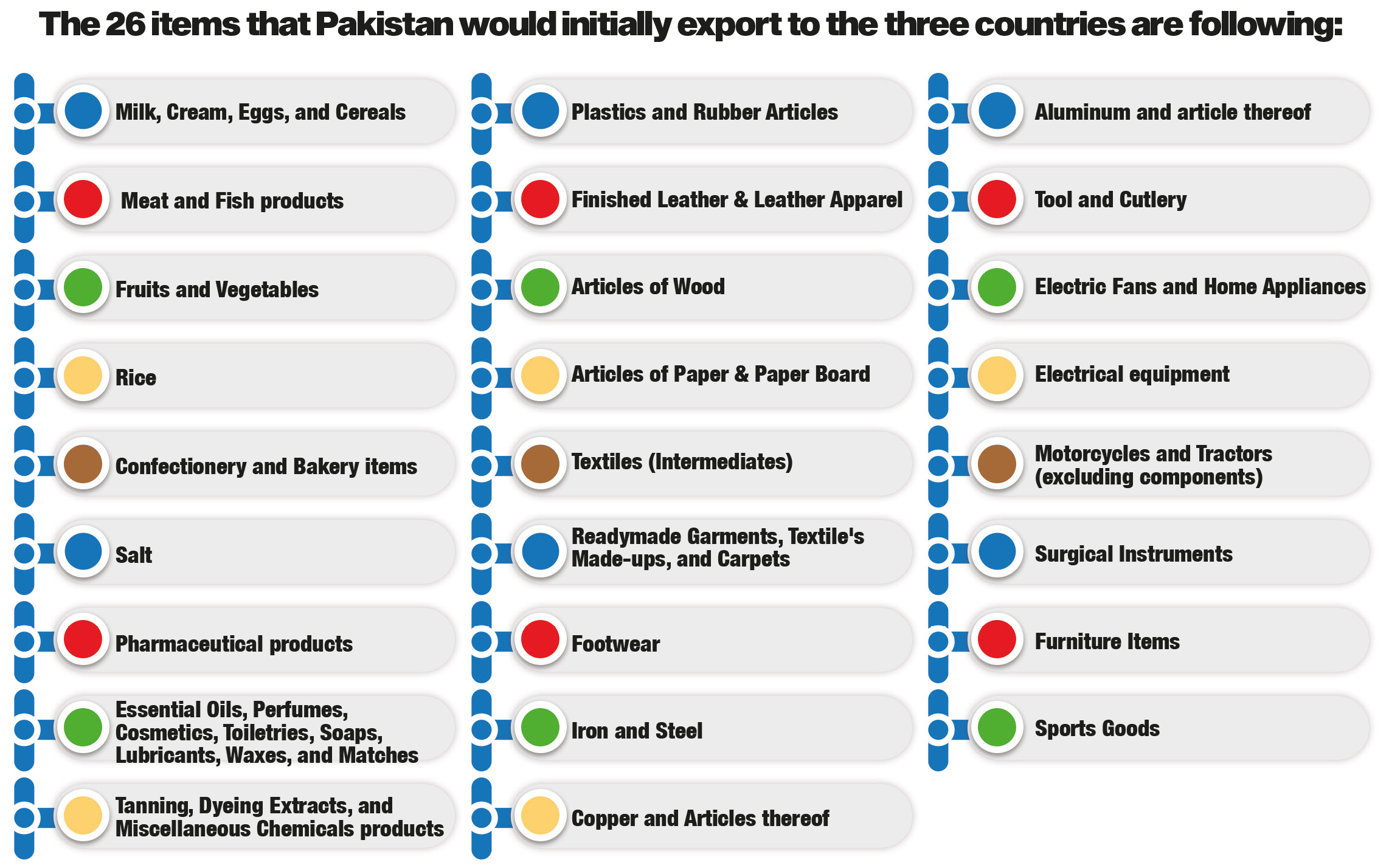

More recently, an option of barter trade with neighboring countries has been explored. Early this month Pakistan passed a special order to allow barter trade with Afghanistan, Iran and Russia for certain goods, including petroleum and gas. The move is claimed to be an option to ‘ease the demand for dollars’ as Pakistan’s government is desperately trying to manage a balance of payments crisis and bring inflation under control after it hit a record of nearly 38% last month.

The government order, called the Business-to-business (B2B) Barter Trade Mechanism 2023 and dated June 1, lists goods that can be bartered.

Although the Barter Trade agreement (BTA) signed by Pakistan is being portrayed as a big achievement to boost exports and enhance bilateral trade, there is a lot that remains unexplained and does not make a lot of sense. In this story we attempt to explain the mechanics of what has been proposed and whether or not it is implementable in the presence of modern day trade and.

How will the barter system work?

In short, it is a very difficult mechanism to implement effectively enough to make the gains that the government has claimed it will make through this agreement, which is to reduce the dependence on USD for trade and arrest the increasing imbalance in trade with other countries.

Much of the procedure under which this trade will take place has been defined in an SRO issued on June 1, 2023. It is evidently not dissimilar to conventional trade rules and regulations with the text saying, ‘The trade has to comply with Import and Export Policy Orders and meet all relevant regulatory requirements, including permits, licenses, certificates, and quotas specified in the IPO and EPO’ and ‘applicable duties, taxes, fees, and charges are levied on imported and exported goods’.

The process is defined as “import before export”. ‘Pakistani traders are responsible for netting off the value of goods within 90 days after receiving authorization’, the relevant section of the SRO goes on to say.

The SRO doesn’t tell us much. It is difficult to understand and problematic to implement. Let’s say an Iranian pulses trader and a Pakistani wheat trader want to make a deal. According to the SRO, the Iranian trader will export an X amount of pulses at an agreed upon rate first. Within 90 days, the Pakistani wheat trader will send what he owes to his Iranian counterpart in equivalent volume.

Under what circumstances would a wheat trader in Pakistan find a pulses trader in Iran in search of wheat for his pulses, or vice versa? It is highly unlikely.

But let’s assume such a deal is struck. How will the two equate volumes to reach a fair deal with the price of both commodities already established for that particular day in their respective countries, wheat and pulses price in Iranian Rial for Iran and the prices for the same in Pakistani market in rupee? Will both commodities be priced in USD? There is not much clarity on this.

Lastly, a lot can happen to the prices of both commodities in 90 days, in either country. Will the deal be renegotiated if such a price movement occurs? Isn’t Iran, the exporter at the first stage of the transaction who will later become an importer of wheat as payment, at an obvious disadvantage? The pricing mechanism is so far unclear.

Some clarity, but not much

Profit spoke to Joint Secretary Ministry of Commerce, Usman Qureshi who is dealing with the barter trade initiative to get some clarity on the matter.

“It is the responsibility of the local importer/exporter to make arrangements for both the importing/exporting goods and all deals with his/her partner in another country (of the three countries)”, he added.

While researching for this story Profit came to the conclusion that the only plausible mechanism through which barter trade could be done effectively was the inclusion of a third party, a middle man, on both sides of the border.

Qureshi concurred, stating that the role of a third company may be needed for those interested in barter trade to deal with the difficulties in the exchange of goods.

“Trading companies may be consulted by traders for this business”, he added.

The only way it works

There would technically be two layers to this sort of cross border trading. The first would be the actual buyers and sellers of specific goods. But as mentioned earlier, it would be impossible for them to exchange those different goods with each other. This is where the second layer comes in, the middleman, on both sides of the border.

Let’s demonstrate how this would work using an example. In Pakistan, there is a wheat mill owner (company A) looking to take advantage of the BTA and a Russian oil refinery (company B) wishing to do the same. However, as already established, the wheat miller has no use for Russian oil and vice versa. This is where the middleman comes in.

Company A will engage a local trader (middleman A) dealing in multiple commodities and company B will do the same in Russia (middleman B). As far as the companies are concerned, they are only selling their goods to their respective middlemen and receiving payment at an agreed upon market price, minus the commission the middleman will charge for his services.

The middlemen’s task is a bit trickier. Middleman A needs to find a buyer of Russian oil in Pakistan. Similarly, in Russia, middleman B has to find a buyer of wheat. Once both middlemen connect, they will negotiate a price for the commodities they have already bought; wheat in Pakistan against oil in Russia.

Middleman A strikes a deal in Pakistan with a local refinery for 10 barrels of Russian crude oil at the rate of $100 per barrel; a total cost of $1000. He proceeds to convey this demand to middleman B in Russia, perhaps he keeps a small margin as well. Middleman A then conveys that he has wheat to sell for the oil he requires. Middleman B agrees to take the wheat after locating a buyer in Russia. He negotiates a price for wheat in USD that has to be equivalent to $1000. Let’s say this is agreed at $10 per kg of wheat, which would mean a 100 kg of wheat going across the border to Russia to middleman B.

What happens as a result is that goods of equal value are exported and imported from each country, which is what the government wants out of this deal; balanced trade.

Complicated? Yes. Workable? Perhaps. But this is the only conceivable way in which what is being proposed and marketed by the commerce ministry can work. And as evident from the example, a lot needs to be just right for such deals to be executed effectively.

No wonder then that the joint secretary at the commerce ministry said that the import and export of goods in exchange for goods is “quite difficult”!

The obvious pitfalls

To begin with, even though multi-commodity traders will be involved in the process, they will be hard pressed to locate a similar trader from another country who is in the market for what the former is selling. This would be a universal problem for traders in all three countries.

What may happen as a result of this search for ‘buyers across borders’ is the inclusion of more than one middleman within each deal. This will almost certainly lead to squeezed margins and perhaps as a result, the deals may not remain as profitable for the middlemen. Volume of barter trade would reduce as a consequence and not contribute enough to trade to remain sustainable.

There is also some ambiguity over the scale and what sort of importers and exporters the government has kept in mind when preparing this multilateral trade policy. According to Qureshi, the barter trade agreement is mainly designed or proposed for those doing small trade at borders or already involved in business across the border (of the elected countries).

On the other hand Minister of State Musadik Malik is on record stating that “oil purchases could rise to 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) if the first transaction goes smoothly”.

Keeping aside the clear confusion and ambiguity within the commerce ministry over who the BTA is targeted at for a second; there are technical problems with both statements.

Why would small traders already engaged in trading, presumably falling under the informal trade category, be interested in barter trade that brings them within the formal economy? Why would they disrupt relationships built over years of doing business with these countries to participate in a move that is fundamentally a bandaid over a gunshot wound for a government that keeps shooting itself? It would also not make much sense for most of these smaller traders to change their entire system of trading with currency without seeing any tangible benefit in switching to barter trade.

As for Mr Musadik’s anticipation of ‘100,000 bpd’, things become a lot more complicated when dealing with larger ticket items such as oil and petroleum products. What Pakistan has on offer to exchange is much cheaper in dollar terms and therefore a lot more of it will have to be exported. Additionally, Russia would be under no obligation to trade oil under a barter system if Pakistan is a willing buyer. They would much prefer to go through conventional channels, similar to how Russian oil was imported last month.

As per Qureshi, an exercise to educate various traders, exporters and importers is still underway, even though the SRO has been issued. Clearly, this step should have been completed before the launch of the barter trade option.

But it seems even those meant to educate the traders are unaware of how this type of trading will work effectively at the level of importers and exporters.

Quotas and shortages

One concern that arises from such trade is the shortage of goods domestically. In an attempt to trade eggs, wheat and sugar for oil, won’t Pakistan face a domestic shortage as a lot more of the former will have to be exported to import the latter?

That’s what quotas are for. Right? But surprisingly, according to Qureshi there is currently no limit or quota fixed for the import and export of agricultural items under the barter agreement. He added however that if a domestic supply issue arises the relevant authorities may restrict and impose a ban on such goods in the same way the government practices in existing normal trade.

Pakistan is already prone to domestic supply issues owing to various reasons. The sugar and wheat crises under the PTI government were a direct result of too much of both commodities being exported. Is it not unwise to create additional avenues for such shortages to spring up and, as per the joint secretary’s statement, ‘deal with it later’?

Trade deficits

Pakistan runs a trade deficit with all three countries proposed in the barter trade agreement. As of FY 2022, Pakistan runs a $84.8 million trade deficit with Afghanistan, $462 million deficit with Iran (export figure based on Iran custom’s data) and a $333.2 million deficit with Russia.

Barter trade would not improve these figures as in every deal under the agreement, an equal dollar value of exports and imports would be taking place; there would be no new imbalances being created.

This is beneficial and preferable to free trade agreements (FTA) that Pakistan has previously had with countries like China for example. Being a net importer of most goods and services, under FTAs Pakistan tends to import more than it can export, creating a greater outflow of precious foreign exchange reserves and creating greater deficits with trading partners.

The BTA would help in maintaining the deficits at their current levels while continuing trade. However, the primary issue still remains; it does not seem to be implementable on the scale that would be as beneficial as being marketed.

Customs handling

There is more clarity on the customs front since this element of trade is not particularly associated or involved in the technicalities of how goods are bought and sold between trading parties and will be following already established and defined procedures.

According to the SRO issued for the BTA the procedure for assessing the valuation of the products is defined as ‘the assessed value of goods used to calculate the monetary limit of the authorization, ensuring compliance. ‘Import and export values should not exceed the authorized monetary value entered in the WeBOC system.’

WeBOC is a web-based computerized clearance system, providing automated customs clearance of imports. It is a portal through which the Customs valuations of various goods and services can be determined based on historical data of invoices being posted there by importers. These valuations change according to data to remain valid and current.

The same valuations and procedures will be used to determine the duty to be charged on goods being traded under the BTA as with conventional trade. As per multiple customs officials who spoke with Profit on the matter, customs officers present at the borders will calculate and determine the payable duty.

As per the SRO, any export and import good valuations differing from the WeBOC system values will be allowed a ‘one-time tolerance’ of 20 percent.

Speaking to Profit Member Customs Operations Mukarram Jah Ansari clarified that the general proposed process in barter trade to first import and then export up to the value already imported. However, if at some point, the value of export is greater than import, then flexibility of up to 20% would be allowed on a one time basis.

BTA and smuggling

The BTA is unlikely to resolve or add to the smuggling at borders. Iran, which is part of the B2B barter trade agreement, is involved in massive smuggling of oil into Pakistan. As per a Reuters news report from May of this year, Pakistan Petroleum Dealers Association (PPDA) claims

that 35% of diesel sold in Pakistan had arrived illegally from Iran.

The same report mentioned that the federal energy ministry had asked security forces to clamp down on fuel smuggling from Iran as diesel sales had slumped “more than 40%” due to smuggled products.

This practice will continue unless a strict top-down crackdown takes place. According to Ministry of Commerce officials barter trade would enhance existing smuggling from these countries, especially from Iran, Afghanistan. This makes sense as anyone already thriving in the smuggling business, as is the case with Iranian oil at least, will not delve into a well-monitored system of trade looking for more innovative ways to smuggle more.

Not the best idea

While the barter trade agreement signed by Pakistan with Iran, Afghanistan, and Russia aims to address economic challenges and foster closer ties, it is evident that this agreement has significant procedural issues that need to be addressed before any deals can take place. Problems that will prop up once a basic understandable and workable mechanism is in place are also serious in nature and plenty.

The potential risks associated with such arrangements, including the complexities of non-monetary exchanges and the effort and resources that have already and will be put in to execute such an undertaking in the future, highlight the importance of conducting a thorough review and further analysis of this agreement.

It is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders to address these drawbacks, identify potential solutions, and ensure that the barter trade arrangement can be sustained in a manner that is beneficial to long-term economic stability. And if such a possibility does not exist, going forward with it just for the sake of it would be ill-advised. Bilateral trade of this nature does not take long to evolve into full-blown diplomatic issues that can also lead to international litigation. Such an outcome would be most unfortunate and costly.

On the face of it, it sounds like a good idea. But in modern economic times with well-developed IT based trading systems in place, the case for a barter system is very weak. It seems like more of a political gimmick for a cash-strapped net-importer like Pakistan to stave off some of the attention and pressures of being responsible for a failing economy than an actual solution to serious problems.

Creatail is an online store that sells innovative electronics for people of all ages. Creatail offer a wide variety of products, including gadgets, gizmos, and more. Creatail’s products are designed to inspire creativity and imagination, and we believe that everyone has the potential to be creative with electronics.

Creatail is an online store that sells innovative electronics for people of all ages. Creatail offer a wide variety of products, including gadgets, gizmos, and more. Creatail’s products are designed to inspire creativity and imagination, and we believe that everyone has the potential to be creative with electronics.

talk about trading in Yuan to bypass western sanctions .

We need more innovative approach.