Demonetisation is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can tackle the problems of counterfeit currency, corruption, tax evasion, and inflation but on the other, it can harm the people who rely on cash for their daily transactions. It can shrink the circulation of black money, but it can also trigger cash shortages and chaos. It can speed up the transition to digital payments, but it can also leave out those who lack access to technology.

A government can decide to demonetise for various reasons, and it usually announces a deadline during which the currency — for example, Rs 5,000 notes — can be used or exchanged from banks. But demonetisation is not a magic bullet. It has many risks and challenges, and it requires flawless planning and execution.

It also depends on the context and conditions of each country. What works for one may not work for another. Demonetisation is not just a word — it is a process of removing the legal tender status of a currency, and it has been tried by several countries, such as India, the US, the EU, and Zimbabwe. But is it a good idea for Pakistan?

Why demonetise?

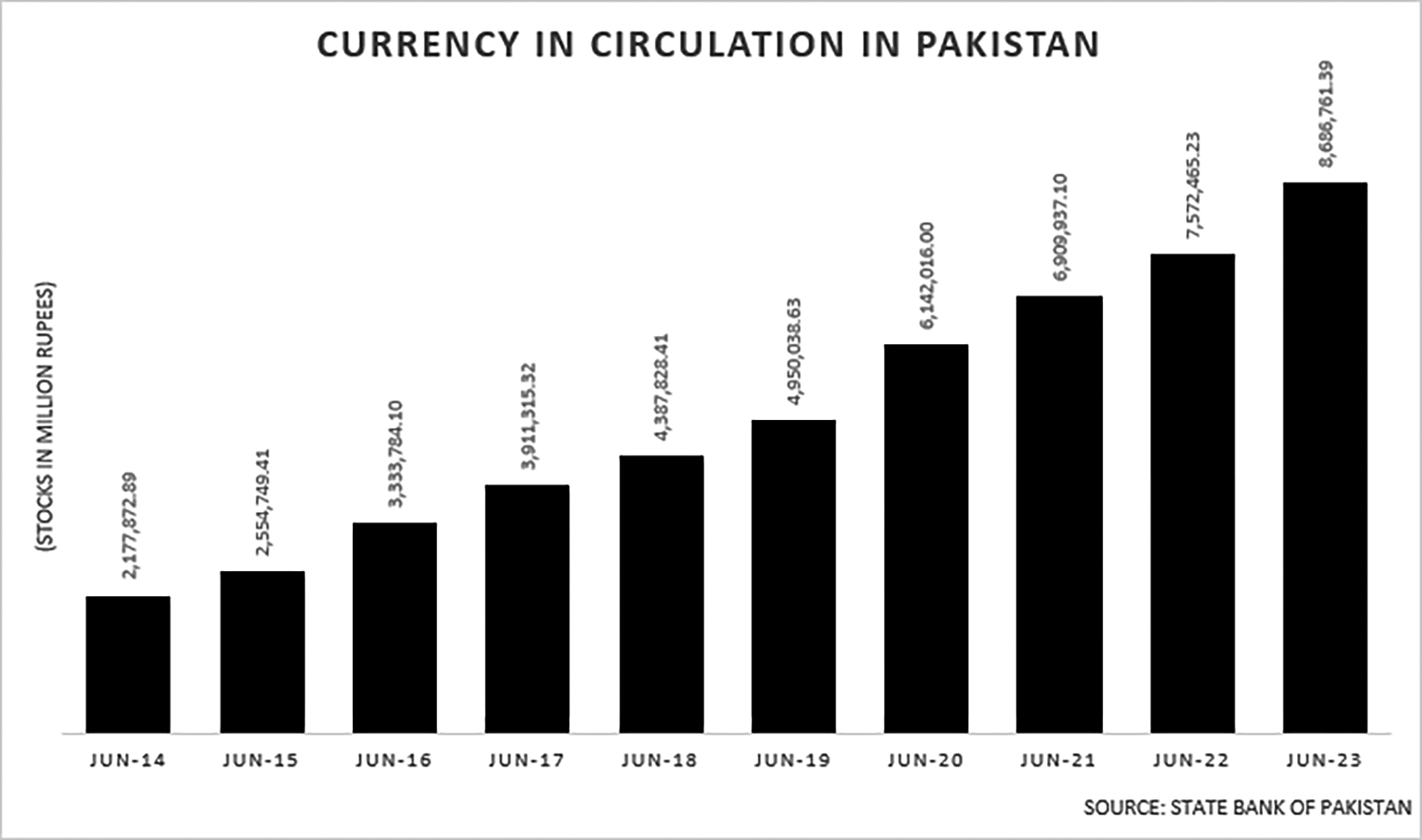

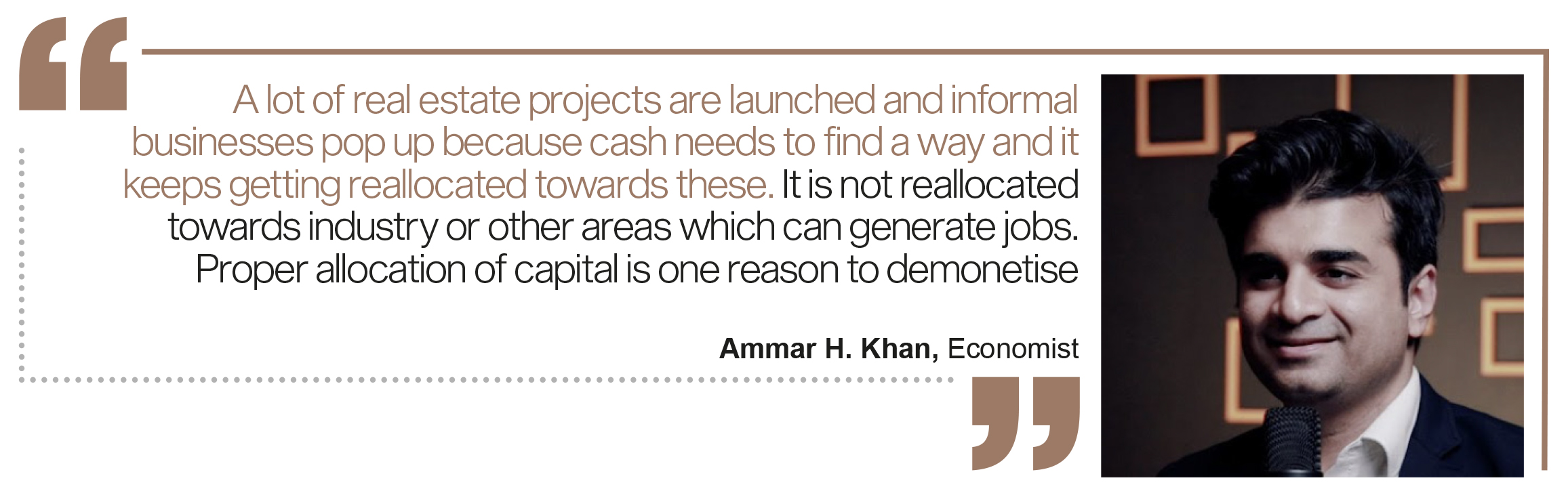

Independent macroeconomist Ammar H. Khan noted that there was a lot of cash circulating in Pakistan’s economy — Rs 8.68 trillion as of June 2023, according to the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) latest statistical bulletin. He said that when this much cash was out in the open, it tended to find its way into sectors such as real estate.

“So, a lot of real estate projects are launched and informal businesses pop up because cash needs to find a way and it keeps getting reallocated towards these. It is not reallocated towards industry or other areas which can generate jobs,” he explained. “Proper allocation of capital is one reason to demonetise.”

Secondly, he added, higher currency in circulation also drives inflation, which rose to a record high of 37.97 percent in May. Khan elaborated that when cash is not being used for productive purposes, a country’s dependence on imports increases. So, eventually, the excessive cash in the economy drives more consumption and that consumption is supported by imports. Pakistan does not have the dollars to fund these imports, he pointed out.

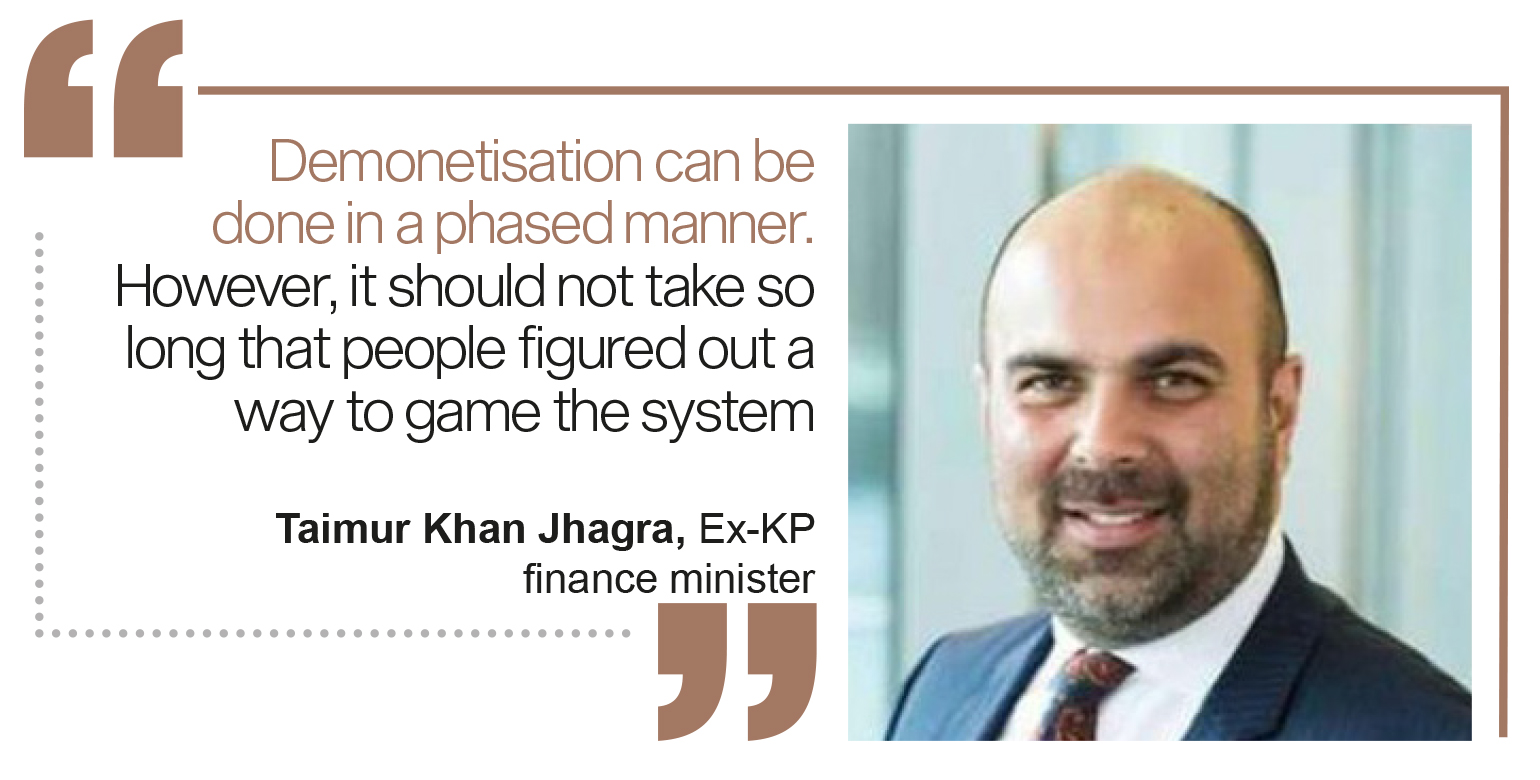

And former Khyber Pakhtunkhwa finance minister Taimur Khan Jhagra said that in the context of creating barriers to the informal economy, demonetisation was “definitely worth considering”.

“In the context of bringing more of the grey and black economy [into the formal economy], we need to consider demonetisation as well as any other steps that will do the same. So, for example, encouraging transactions through credit cards, or other forms of e-payment etc., and incentivising those.”

A good idea or just more pain?

A senior banking professional who spoke to Profit noted that Pakistan’s economic situation was bordering on “precarious” with foreign exchange reserves down to $ 4.46 billion as of June 30, 2023, inflation close to 30 percent, interest rate at a record high of 22 percent and many other factors that indicated a weak economy.

“Demonetisation is best done in stable economies, in which central bank reserves are adequate, inflation is low and GDP growth is decent to high — four percent. It will be regressive if it is done in this current environment when inflation is peaking [and] the economy is in the doldrums. Demonetisation at this point will only cause further nuisance for the general public. We are already burdened with inflation and high taxation, both direct and indirect.”

He added that the effects of demonetisation lasted for several months, which would be a terrible idea given Pakistan’s fragile economic situation.

However, Khan said that while the process of demonetisation would be complex and challenging, not going ahead with it would only mean prolonging the economic pain. “Might as well take the pain today instead of tomorrow,” he commented.

The banking professional also acknowledged that demonetisation could be a good idea for Pakistan under better economic conditions with certain prerequisites in place. One of the things that Pakistan would need prior to demonetisation was a proper digital banking infrastructure that would be able to sustain the exponential number of transactions that would result in the process, he said.

“The current infrastructure, unfortunately, is inadequate. It’s weak. When India went for demonetisation in 2016, it had the UPI digital banking system in place. So, it was able to sustain the impact of demonetisation and kind of smoothen the journey for the general public from cash to digital. So, from our perspective, I don’t think we are ready for it as of yet from the digital banking standpoint and also from the economic standpoint,” the banker said, noting that Pakistan kept going through boom-and-bust cycles — a process of economic expansion followed by contraction that occurs repeatedly.

Addressing this, Khan said demonetisation was actually a way to fix Pakistan’s boom-and-bust cycles. He elaborated that the country went through these cycles because it started consuming more, which in turn, required dollar-based imports. Demonetisation would help fix this as it would mop up the surplus cash in the economy and reduce consumption, Khan said.

However, it all depended on policy decisions, the economist continued. “When all this cash comes back into the system, how will the government reallocate it? Does it go towards imports or does it get reallocated towards a more productive area? So, demonetisation is the first step. Capital allocation is the second step that needs to be done.”

One effect of demonetisation is a rise in cash deposited in banks, potentially increasing the amount available to them to lend to businesses and spurring economic growth. The senior banking professional said, however, that in Pakistan’s case, the impact would be minimal.

“Let’s assume that of the currency in circulation (CIC) in Pakistan right now, Rs 3 trillion is in the form of Rs 5,000 banknotes, which are demonetised. This cash comes back into the banking system.

“However, Pakistan’s government is running a perennial deficit. Consequently, it is borrowing more and more. The incumbent government has borrowed Rs 3.5 trillion in the past 13-14 months, which is potentially more than the inflows [from demonetisation].”

If the government continued to borrow from commercial banks at a rate of Rs 500-600 billion a month, then demonetisation, which would be a one-off measure, would have a “very temporary” effect, the banker said.

The effect on small businesses would also be zero in Pakistan’s case because its commercial banks traditionally do not lend to consumers or small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as they consider them to be “high risk”, he said.

“If demonetisation happens and money goes into the banks, the only beneficiaries are going to be those who were previously beneficiaries as well as large enterprises and conglomerates etc. So, SMEs, the agri sector, small businesses and individuals etc. will not see a positive impact because they will still not be lent money by the banks.”

What needs to come before

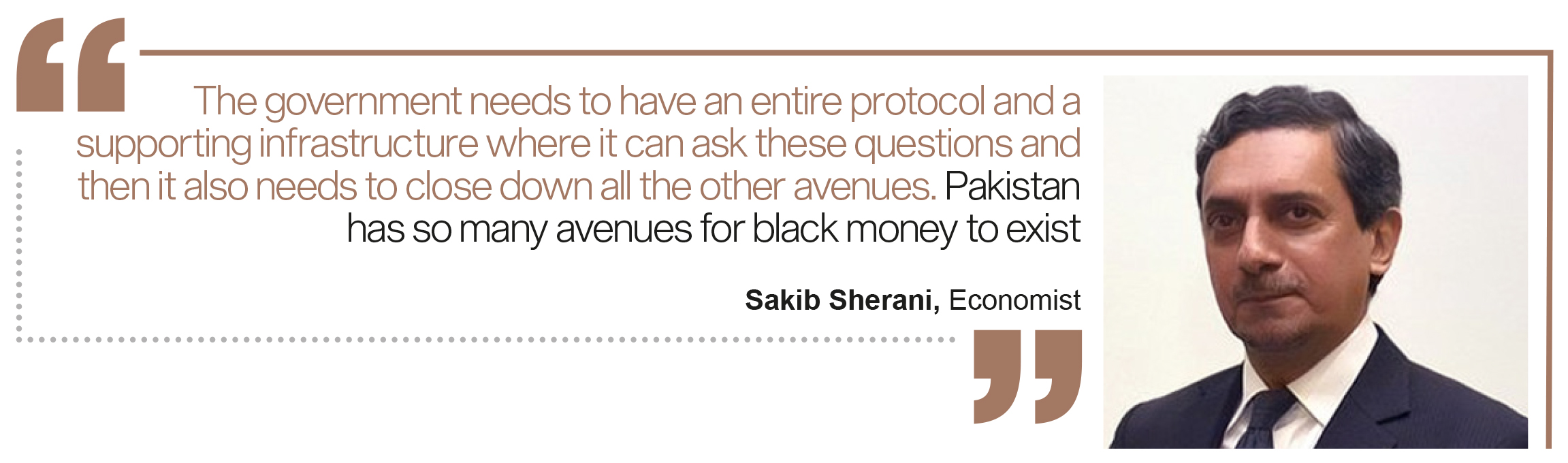

Economist Sakib Sherani, who has been part of economic advisory councils under different prime ministers, said that while demonetisation has its pros, people need to be careful about the idea as it could potentially cause a lot of disruption in developing economies.

Of the demonetisations that have happened around the world, very few have been successful, Sherani said. “The ones in developed countries have generally been more successful, but the ones in developing countries have been less successful and there’s a reason for that.”

This is because demonetisation could not be done in a vacuum, he explained. So, for instance, if the government withdrew Rs 5,000 notes from circulation, it would have to provide more notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 instead. Besides this, it would also need tax authorities and banks to have the proper infrastructure, instruments, and details of a framework to ask questions of people who brought in large amounts of that currency such as a sack full of Rs 5,000 notes.

“[The government] needs to have an entire protocol and a supporting infrastructure where it can ask these questions and then it also needs to close down all the other avenues. Pakistan has so many avenues for black money to exist,” he said, adding that the real estate sector among others needed to be taxed.

Meanwhile, Khan said that one con of demonetisation would be the trouble people would face in depositing their cash in banks, but there were ways to mitigate this. A presidential order could be issued to mandate that anyone who had a CNIC would also need to have a bank account, he suggested. Everyone could be given a period in which they could deposit the cash, for example, three months, and the government could impose a tax on anyone who had undocumented cash beyond a certain limit.

Jhagra also said that demonetisation could be done in a phased manner. However, it should not take so long that people figured out a way to “game the system”, he added.

The ex-minister said the government would need to evaluate which segment would be impacted most by demonetisation. “I think it would primarily still hit large cash transactions by a group that tries to stay out of the tax net.”

Demonetisation and taxation

Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio — a figure to gauge tax revenue relative to the size of the economy as measured by the GDP — has remained between 8.4 to 9.8 percent over the last seven years — one of the lowest in the world. It was measured at 9.6 percent in FY23.

Can demonetisation reduce tax evasion? Khan said that once demonetisation happens, cash will come into the economy and evasion will “automatically reduce”.

“That’s the whole point. The surplus capital will come into the system and [the government] can tax it. If it does not want to tax it, that is a different story. Every single person in the world does not want to pay taxes. A structure needs to be in place in which people are forced to pay taxes.”

Therefore, demonetisation would need to be accompanied by Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) reforms, he added. This was what Jhagra said as well.

“In this case, demonetisation is not a stand-alone initiative. It is part of an overall drive to get rid of or reduce the size of the informal economy. It would need to be accompanied by some [reform] drives at the FBR in terms of ensuring tax collection. It would be accompanied by bringing traders and large parts of the informal economy into the tax net,” he said.

“I would do demonetisation as part of a compendium of three or four major reforms so that it signals that we are actually breaking down the informal economy. In the current system, staying outside of the tax net and the formal economy is actually legal. You can choose to be a non-filer,” the former minister noted.

Meanwhile, Sherani spoke about the loopholes in Pakistan’s taxation laws. There is an entire section in the Income Tax Ordinance 2001 that allows people to bring in dollars to Pakistan without any questions asked, he pointed out. The economist was referring to ‘Part VII – Exemptions and Tax Concessions’ of the ordinance. Over the last 20-40 years, people have been converting money that originated from certain untaxed, unreported, or illegal activities in PKR and converting it into dollars, sending it abroad, and then bringing it back into the country using the loophole, he added.

“My whole point is that you just can’t do something without all the other important supporting instruments and frameworks,” he stressed.

He also emphasised the role of cashless transactions in widening the tax net as it would “close all other avenues [of evasion]”.

While acknowledging that demonetisation would force people to deposit their Rs 5,000 notes in banks which would broaden the tax net, the senior banking professional said it would “once again have a one-time impact” because of the prevalent culture of tax evasion.

People would continue to look for ways to evade tax, he said, adding that this was why FBR reforms, strong tax machinery, and the right infrastructure were needed before initiating demonetisation, he added.

He pointed out that despite multiple International Monetary Fund (IMF) programmes, successive Pakistani governments chose not to tax the agricultural sector which makes up 30 percent of the country’s GDP. Taxes on real estate were low whereas taxes on the retail sector were either zero or non-existent, he added.

“A serious government would have already gone on to tax these sectors first. In my view, the government should be looking at the existing tax collection potential. If you look at the agricultural rent for land in Central Punjab, right now it is between Rs 150,000 and Rs 400,000 per acre. So, the agri rental income in Punjab and Sindh has gone up by four to six times. Whereas the tax paid on that land is zero.”

The India example

While several countries have demonetised currencies over the years, the most famous example is India. On November 8, 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in an unscheduled television address that the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes — which accounted for 86 percent of the currency in circulation — were “just worthless piece[s] of paper” effective immediately. The public was told that it had until the end of the year to exchange the currency for new notes of Rs 500 and Rs 2,000, with the government framing the move as a measure to deal with corruption and black money.

This led to widespread chaos as long queues formed at banks across the country and a liquidity crisis was created. Sherani cited India as a cautionary tale and said it was a prime example of the disruption demonetisation could cause in developing economies. “It has been eight years and economists say the ripple effects are still being felt. Obviously, the government has [imposed] secrecy on how much damage was done but independent studies say that it ended with deep repercussions on small businesses and households.

“So, Pakistan needs to be careful. If we do decide to implement demonetisation, we have to plan it carefully, in a particular sequence, and it has to be done gradually.”

In a report written for Next Capital, former finance minister Hafiz Pasha noted that the percentage of currency in circulation in India as part of its gross national product declined rapidly post-demonetisation. However, it recovered strongly later, so much so, that the figure stood at 11.73 percent in FY21 compared to 7.7 percent in FY17 following the move to demonetise.

Separately, the senior banking professional also said that while demonetisation contributed to the increase in India’s digital transactions, COVID-19 had a greater impact. In FY21, India’s digital banking transactions were worth INR 5,554 crores, which was the first year of COVID. The transactions went up to INR 8,840 crores in FY22, and then INR 9,192 crores in FY23, according to data from India’s Press Information Bureau.

“So COVID, I think, had a greater impact on increasing digital banking and digital transactions as compared to demonetisation,” he commented.

Can a government do it?

Can a government, including a coalition such as the present one, actually push through demonetisation? Sherani believes the incumbent government or any other government with a similar sort of makeup and credentials would not demonetise “simply because they have very large constituencies that are in the untaxed or very lightly taxed sectors”.

“It is either agriculture or trade or the real estate sector. But these three sectors alone make up about 50-60 percent of the economy, so in that sense, it requires a government with political will, but also with a much more reformist makeup than the governments we have seen in Pakistan, especially this particular government.”

Meanwhile, when mentioned to Jhagra that economists appear to be divided on demonetisation, the former provincial minister commented, “Economists and lawyers are always divided on everything.”

He was also adamant that lawmakers stop thinking of political repercussions in terms of fixing the economy. “When you need to deal with a complex but critical issue, you are not going to wait to develop consensus, you are going to do your homework and implement. I think it is a fair assumption to say that if we (KP government) had not traversed the journey of pension reforms, the federal government would not have done it now.”

“And so similarly … in terms of fixing the economy, the political cost cannot be questioned because those political compromises lead to plenty of political costs anyway. The current turbulence is linked to the fact that the economy is in bad shape. There has been a political cost to that anyway. The government is fearful of elections because they know that they are unpopular and they have shied away from many economic decisions. But if people are experiencing economic pain anyway, why not use that as a building platform and get through difficult reform?” he asked.

Pakistan has a very large and thriving shadow economy at present. According to a global research report of Ipsos on tax evasion published in 2022, its size is estimated at a whopping 40% of GDP. Demonetisation is one way to address this but clearly there are a lot of things that can go wrong if implemented in a country such as Pakistan where even more factors have to be just right in order to even think about such a major shake-up in the economy. Until the political and economic situation in the country is relatively stable, demonetisation may only remain an interesting idea to debate, not a serious policy proposal that is intended to be implemented fully by an elected government.

Nonetheless, there is a case to be made about its necessity in a system as stubborn as ours when it comes to reforms, that can address the problem of tax evasion and a general culture of nonchalance towards paying taxes and being part of the documented economy.