The onslaught of Pakistan’s inflation is no longer limited to the debilitating living standards of its people but rather has seen to place all the country’s CEOs at a difficult juncture. Rising prices intuitively signal one prominent problem for companies: as raw materials or inputs become more expensive, the costs of production also increase. With the pressure of compensating employees in time of rising expenses as well as not transferring the burden of costs onto the consumers, the CEO is confronted with difficult decisions. In such circumstances, the quickest solution would be to increase all wages by the same percentage as the inflation rate. But perhaps the reason why the first lesson in Economics 101 is that of limited resources, is because scarcity is a more pertinent problem than usually perceived. There are two prominent reasons why raising wages by a flat percentage amount is not feasible: firstly, it would pose a tremendous financial burden on companies whose profitabilities are already compromised as explained above, and secondly, it would also not benefit all income brackets equally– which will be explained in detail later on in the article. Hence, a problem unique to inflationary pressures, is the task of determining how to best compensate the workforce.

Pakistan’s Year on Year inflation has grown to 27.55% from January 2022 to January 2023, but the latest Year on Year inflation rate recorded for the month of July stands firmly at 28.31%. This results in some keen glances towards the corporate sector, and nudges all employers to amend their wages and salaries according to the exponentially increasing living costs. But whether or not Pakistan’s businesses have managed to account for all variables in their calculations is up for debate.

Imagine this, you’re the CEO of a firm that has two employees: a software engineer and a security guard. They are each paid Rs. 500,000 and Rs. 40,000 respectively.

You read a Profit headline that reveals Pakistan’s Y-o-Y inflation has increased to 28.3%, and so in the quest of being an empathetic boss, to recompense for inflation you decide to increase employee wages by 28% as well. However, as the wave of reality hits, you realize that a 28% increment would add an additional fixed monthly cost of more than Rs. 151,000 which is an unsustainable amount given your limited resources. Additionally, you also realize that a flat increase impacts each income bracket differently such that the engineer would benefit from a higher net increase of Rs. 140,000 than the security guard whose income would only increase by Rs. 11,200 if the increment is implemented. Moreover, each of your employee’s income is also contributing to distinct expenses which take up a different proportion of their income– ultimately rendering such an increase inadequate.

To really help paint a picture, if the engineer and manager, with the same original wages stated above, spend Rs. 80,000 and Rs. 15,000 on non-perishable food items, then only their food consumption expenditure should account for 16% and 37.5% of their total income. With an inflation of 28%, however, food expenses would further increase to Rs. 102,400 and Rs. 19,200, and therefore, the proportion of food expenditure to income would also increase to 20% and 48%. The point to note, therefore, is that there is an unequal increase in consumption expenditure for both employees, which means that they are unlikely to benefit equally or sufficiently from a flat percentage increase of 28% since their real wages have decreased by percentages unique to their incomes and food expenses..

What this means is that companies, like Nestle, whose 2022 annual financial report reveals an 18% increase in total salaries, wages, amenities, and training from 2021 to 2022, must take bigger steps to provide a detailed overview of the income increases for each bracket. A collective figure of Rs. 7 billion in wage expenses provides little insight on the potential impact to Nestle’s lowest paid employees. Moreover, it also signals that CEOs require a mechanism to assess how the expenses of their employees have grown relative to their income, and then compensate accordingly. As a result, this is most likely to reduce wage costs than if the 28% increment is applied. This is because, in reality, a firm is likely to hire more than two employees and each employee’s consumption expenditure is likely to include a variety of goods and services other than just groceries.

This makes it particularly difficult to compute the effective inflation-adjusted income increase and therefore it is precisely the assistance that Profit aims to provide.

Although the State Bank’s Inflation Monitor revealed that Pakistan’s Y-o-Y inflation in April 2023 is the highest rate of inflation the country has experienced since 1964 with a rate of 36.4%, Pakistan is no stranger to price hikes or its consequences. Wealth and income inequality, as well as the stark disparity in living standards across Pakistan’s socio-economic groups is a topic that has long been explored. But inflation does not only necessitate the revision of living costs and household expenditures; it also impacts wage calculations and labor costs for companies that provide inflation-adjusted incomes.

Inflation causes the value of money to depreciate, such that the same amount of income can purchase less goods and services than before. To illustrate using a mathematical word problem, if Person A earns an income of Rs. 50,000 which she uses to buy 10 books costing Rs. 5000 each, then an inflation rate of 36.4% would increase the price of each book to Rs. 6,820. As a result, the same amount of books now cost Rs. 18,200 more– in other words, her real income (actual purchasing power) has decreased to approximately Rs. 31,000.

Theoretically, rising inflation causes purchasing power to fall by the amount of inflation on a per-rupee basis. This is a concern for firms as well, particularly those that want to ensure that their employees are not drastically impacted by rising inflation. However, what complicates the situation is that a company consists of not only Person A, rather all letters in the alphabet in each tier of its corporate hierarchy. Therefore, as inflation impacts each income group differently, calculating the effective rate of inflation-adjusted wages can be slightly tricky.

Rest assured, the HIES by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics provides comprehensive data to aid the intricacies of such income calculations. The HIES is the Household Integrated Economic Surveys which is a report by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics containing household income and consumption expenditure data for a particular fiscal year. In the HIES, all the variables are disaggregated by consumption and population quintiles which means that the population is divided into five groups in order of their incomes with the first quintile representing the poorest 20% of Pakistan’s households.

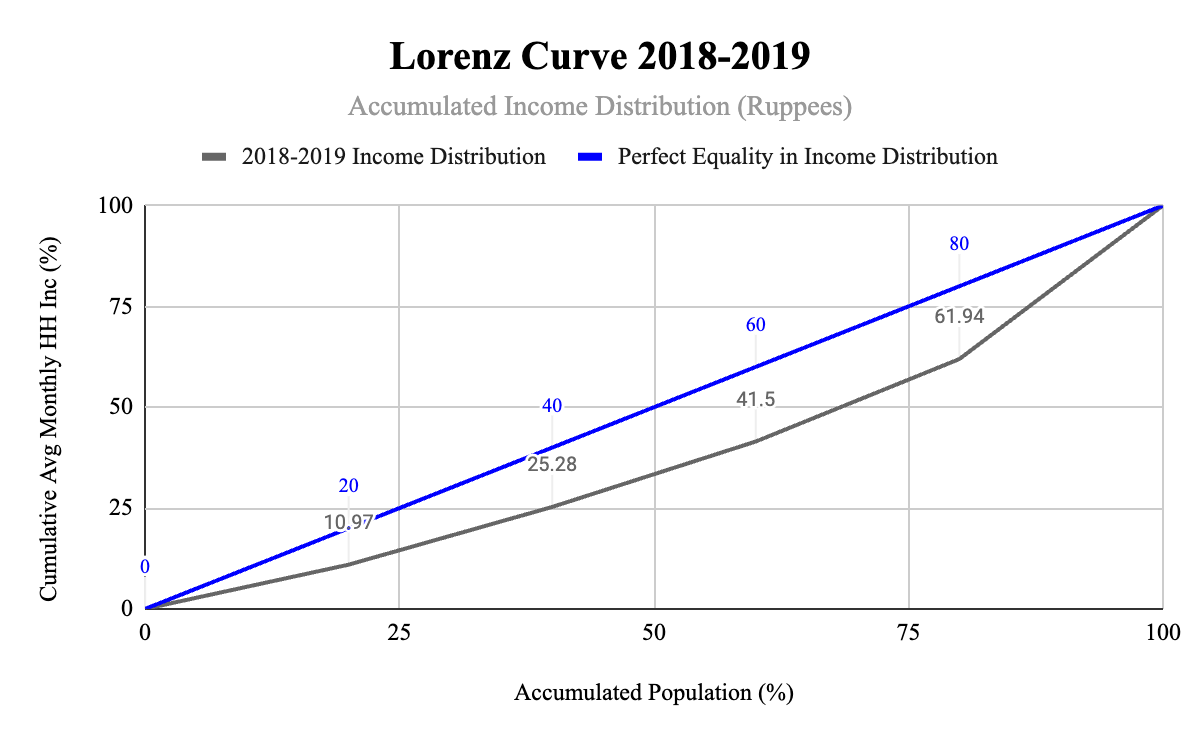

Figure 1, using HIES 2018-2019 data, helps visualize through a Lorenz Curve precisely what the distribution of average income is according to each population quintile in Pakistan. The Lorenz curve is a graphical representation of the distribution of income/wealth. The curve shows the cumulative share of income from different sections of the population and also draws the line of perfect income equality, which shows the distribution of income if everyone earned the same amount– the poorest 20% of the population would gain 20% of the total income. The poorest 60% of the population would get 60% of the income. Figure 1, therefore, helps us understand the inequality in income distribution as it depicts that the poorest 50% of Pakistan’s households earn approximately only 30% of the total average monthly income, whereas the richest 50% earn and enjoy the remainder.

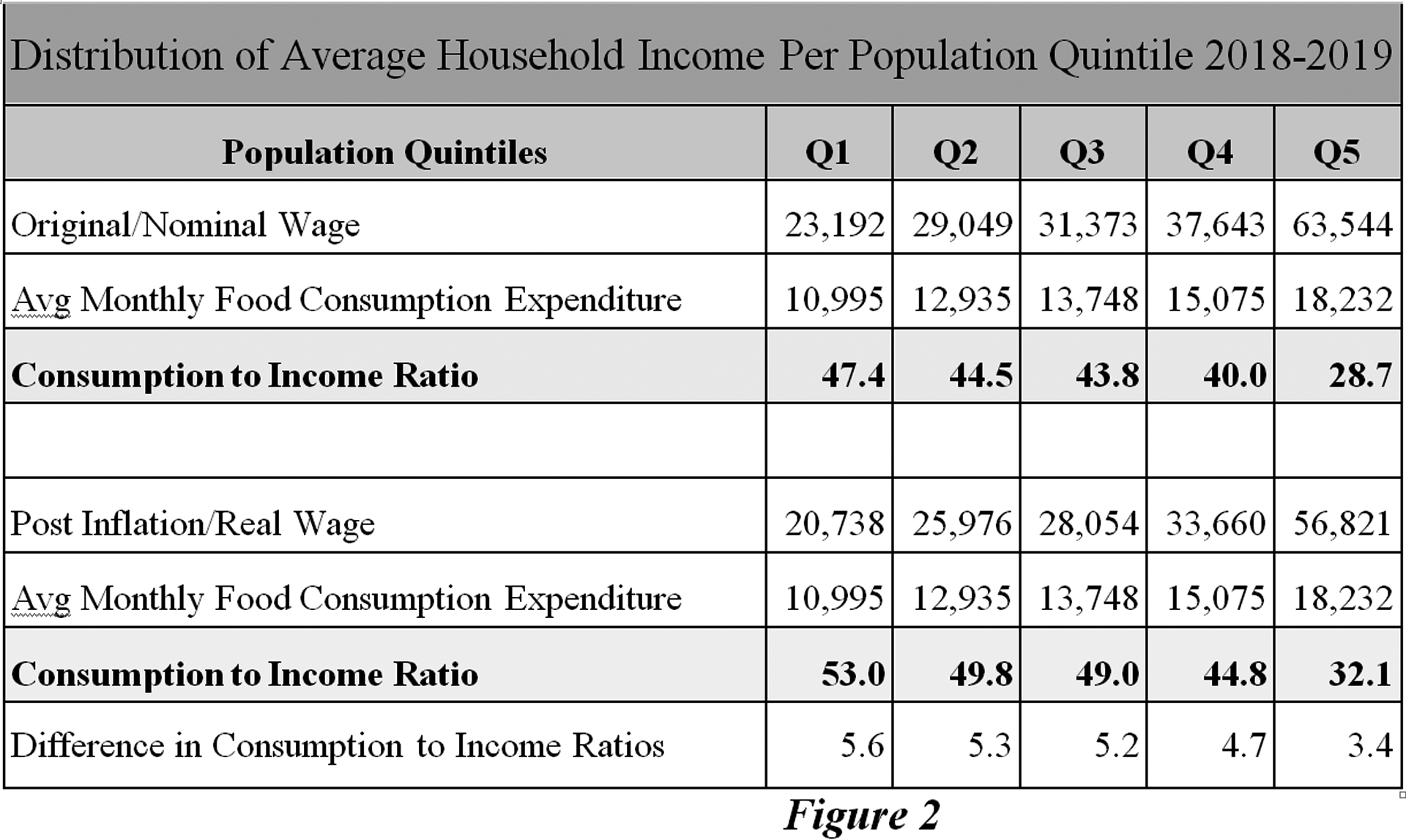

Therefore, since the bottom strata of the population earns relatively less, it is also disproportionately affected by inflation and price changes. Figure 2 below lays out the data for average household income in Pakistan for each population quintile in 2018-2019 as well as the corresponding average monthly consumption expenditure for the same year. Without accounting for inflation, the poorest households in Q1 spent 47.4% of their monthly income on food expenditure, however, following higher inflation, their purchasing power decreased, resulting in the consumption of food to income ratio increasing to 53%. This was the highest ratio recorded amongst all quintiles, making evident the requirement of customizing inflation adjustment rates according to income brackets. The idea in turn is that the incremental increases in incomes must supersede the increase in consumption expenditure caused by rising inflation.

But, what does this really mean?

It means that companies, like Nestle, whose 2022 annual financial report reveals an 18% increase in total salaries, wages, amenities, and training from 2021 to 2022, must take bigger steps to provide a detailed overview of the income increases for each bracket. A collective figure of Rs. 7 billion in wage expenses provides little insight on the potential impact to Nestle’s lowest paid employees.

How can we achieve this?

Step 1: Identify the Correct Inflation Rate

A closer look into the State Bank’s inflation rate calculation of 36.4% presents two methods of assessing price changes: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Sensitive Price Index (SPI). While the CPI provides a comprehensive computation of retail price changes for a basket of 487 items collected from 40 cities, it is calculated less frequently (monthly basis) than the SPI, which assesses the price movements of only essential consumer items at short intervals (on weekly basis ). According to Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), therefore, the CPI is incapable of capturing the price fluctuations which might fade out over the period of a month, while the SPI captures price volatility much better than CPI does, making it a more representative indicator of changes in inflation.

However, since most data reports on Pakistan’s average incomes, like the HIES, provide a monthly assessment of income breakdowns, the following calculations in this article will be using the year on year CPI inflation rates of 28.3% instead of the SPI.

Step 2: Organize Data According to Income Brackets

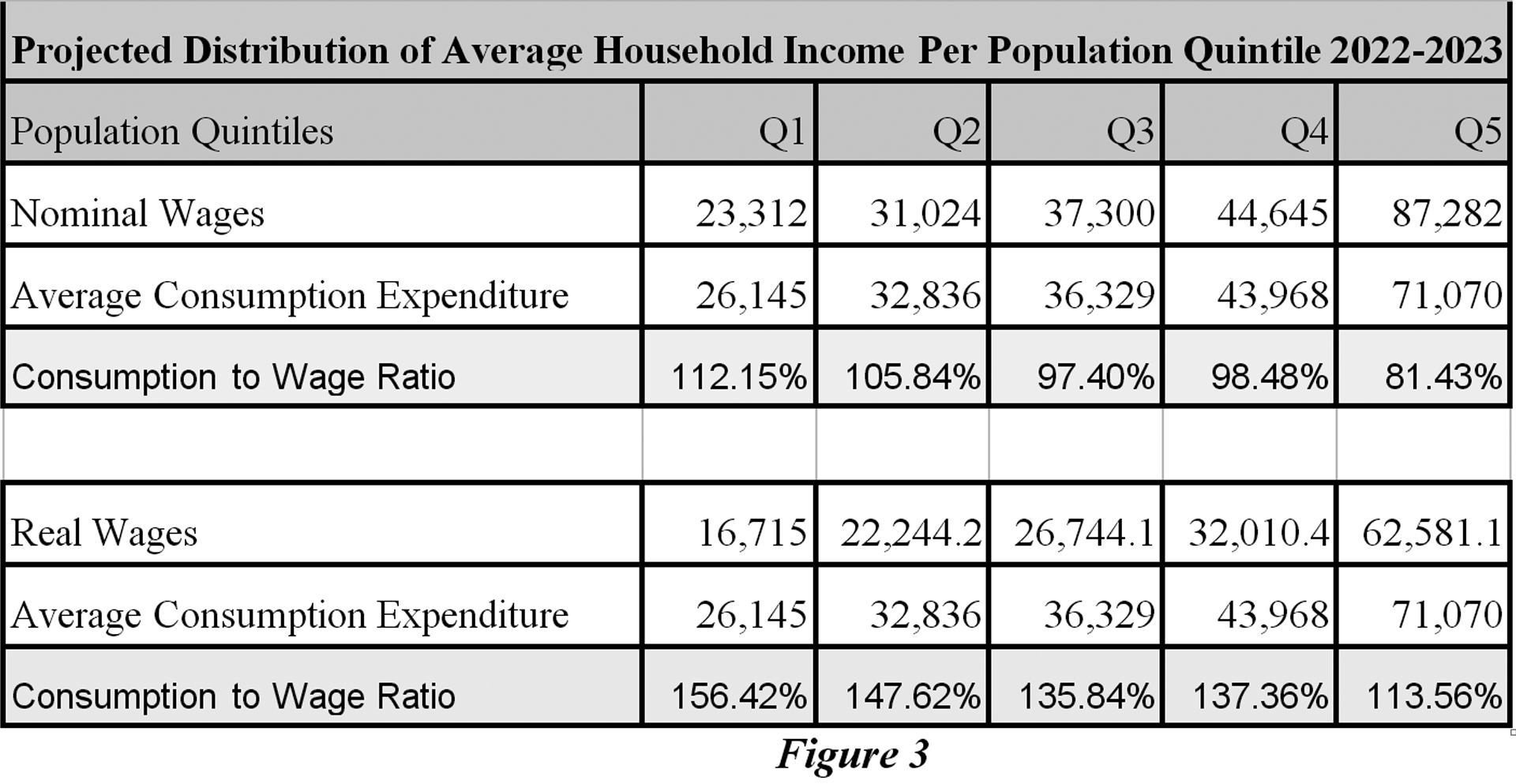

The last Household Integrated Economic Survey carried out by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics was four years ago which means that the latest data on household incomes and expenditure patterns is from 2019. However, using past data and compound changes in inflation rates between 2010 and 2019, the approximate average household incomes for each quintile in Pakistan can be calculated as well as the Average Consumption Expenditures. This is displayed in figure 3 below.

It is integral to note that a government notification was released earlier this month which mandated the national minimum wage to be set at Rs. 32,000. However, prior to this change, for the poorest 40% of Pakistan’s households, the average consumption expenditure– calculated by projecting consumption patterns in the last decade– was exceeding nominal wages. This means that the first two quintiles of the population were most likely in debt as their expenditure was exceeding their income as depicted by consumption to wage ratio (I). Whereas, consumption to wage ratio (II) reveals that when the impact of a 28.3% inflation rate is accounted for, across all population quintiles, consumption expenditure exceeds average monthly income.

Step 3: Account for Consumption Expenditure

In circumstances as dire as these, it becomes imperative to ensure that each person earning an income is provided with a level playing field by accounting for his/her income bracket. For instance, since the real income for the third population quintile reduces from Rs. 37,000 to Rs. 23,723, then not only should their base income increase by 56% to compensate the devaluation but an additional 20% increase should also be granted to ensure that the expenditure to income ratio is maintained at 50%. The values and calculations will differ according to each quintile, which is why a flat inflation adjustment is ineffective.

In easier words, for companies to ensure that their employees at each pay scale are less impacted by rising price hikes they must carry out the tumultuous process of assessing the real wages, which means the real value of their incomes post-inflation. Only then can they effectively increase their wages by the percentage difference in real wages and their actual wages, and additionally offer increments or bonuses to ensure that a relatively smaller proportion of their average income is dedicated to consumption expenditure.