Nobody really wants to be prime minister right now. Well that isn’t strictly speaking true. We’re almost certain that Anwar ul Haq Kakar or any other number of technocrats would love to swivel around in the PM’s chair and jet to and from different countries. What we mean is that no serious politician with any concern for their future in public service would find the current climate less than ideal to get in the driving seat.

There are many reasons why of course. Pakistan is at a corner where the country desperately needs nation building and reconciliation. There is political and social turmoil. The democratic process is broken and Pakistan’s position in the diplomatic world is hazier with every passing day. But perhaps the biggest problem we have is the money. Pakistan owes a lot of money to a lot of different lenders. And while domestic debt and be wiggled out of one way or the other, when international partners come knocking the sweat glands start doing overtime.

But what exactly does Pakistan owe? And how are we planning on paying it off?

How we got here

It is a question of bad habits really. Just look at the past 15 odd years. In 2008 democracy returned to Pakistan and the PPP surged to power. This was the start of Pakistan being on its own after an era of geopolitical significance due to first the cold war and then the war on terror.

In the last 15 years, each party has used different techniques to balance the country’s deficits, by using external finance, one way or the other.

The PPP government in 2008 came into office on the verge of a global financial crisis. The situation warranted them to go on a liberal but necessary borrowing spree. Fortunately for them, not many people were out lending money, especially commercial creditors. During their tenure the government debt increased from Rs 6.44 trillion to Rs 15.1 trillion. This was a 135% increase in a five year period. As a percentage of the GDP, government debt had increased from 62.8% to 67.2%.

For the PML-N government coming in around 2013, the silver lining was that the PPP’s borrowing policy relied more on domestic than external borrowing. Much of this had to do with the prevalent economic conditions around the world, where the Great Recession significantly reduced the ability of economies like Pakistan to borrow money from the international bond market. This meant that the total government external debt increased by only 22pc between 2008 to 2013, going from $42.8 billion to $52.4 billion.

The PML N government when they came to office in 2013, did not have an ideal environment, yet the international market had recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and Ishaq Dar, with the right mix of borrowing and spending, could steer Pakistan in a better direction. Dar’s immediate priority became securing loans from multiple bilateral partners who obliged. During this time Pakistan was also able to secure an IMF program that helped steady the ship.

Over the four years that PMLN spent in office, Pakistan’s external account went up from $60.49 billion to $77.9 billion. Pakistan saw a period of growth but both the commercial and bilateral loans saw a spike. These 4 years more or less had the oversight of Ishaq Dar, PMLN’s long standing finance whizz and someone who is famous for his compulsive control of the economy.

Come the PTI government, Pakistan’s external account saw a meteoric rise from $77.9 billion to $128.92 billion till they were eventually ousted in 2022. During this tenure, the PTI government also tried a number of candidates for the position. Starting with Asad Umar, the long marketed maestro who turned the Engro Corporation around, the PTI government was quick to toss the hat around to Hammad azhar, Imran Khan himself and eventually the same Shaukat Tarin who served in the PPP government as well.

During this period Pakistan received not only multilateral but a lot of bilateral and commercial loans. In particular short term loans saw a rise that proved to be a shot in the foot for Pakistan.

Where we stand

Over the last two years, Pakistan has grappled with twin deficits—a rising fiscal deficit and a surging current account deficit—leading to an increased reliance on debt. This has shot up Pakistan’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 60% to over 75%, as per the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The domestic debts themselves have reached an unsustainable level, with just the interest payments constituting more than 40% of the fiscal budget.

However, a greater threat looms in the form of the persistent foreign exchange liquidity crisis, worsened by the substantial burden of external liabilities.

External debt of Pakistan refers to the total amount of financial obligations that it owes to foreign creditors. This debt includes borrowings from various sources outside Pakistan, such as other countries, international financial institutions, and commercial lenders.

Funds acquired through external debt are deployed to finance development projects, meet budgetary requirements, and address balance of payment deficits. Components of external debt may include bilateral and multilateral loans, bonds issued in the international capital markets, and other forms of borrowing. Hence, any failure to timely disburse external debt has far reaching repercussions on any country.

The government closely monitors and manages external debt to ensure the country’s financial stability and economic development. With a new government about to step into the office, Pakistan’s external account needs to be steered with more care than ever. To look at it in more detail, it is important to look at the external account numbers.

Where do we stand?

One thing that makes the external debt profile harder to predict is the lack of available data. While it is known that Pakistan’s total external debt and liabilities as of December 31st stood at $131.16 billion, we have little to no details on the schedule of the maturities. However, one can obtain quite a snapshot to make sizable estimates of the country’s financing needs for the servicing of external debt, through various reports from the State Bank, the IMF and other sources.

During the State Bank of Pakistan’s latest Monetary Policy Statement briefing, while responding to a question the SBP governor, Jameel Ahmed stated that Pakistan has already paid off a sizable part of its external debt for FY24. According to Ahmed, Pakistan’s external debt payments for 2024 amounted $ 24.5 billion, of which around $3.8 billion was interest payments. He further stated that of this amount, almost $10 billion is due to be paid, of which $5 billion is expected to be rolled over by the respective creditor.

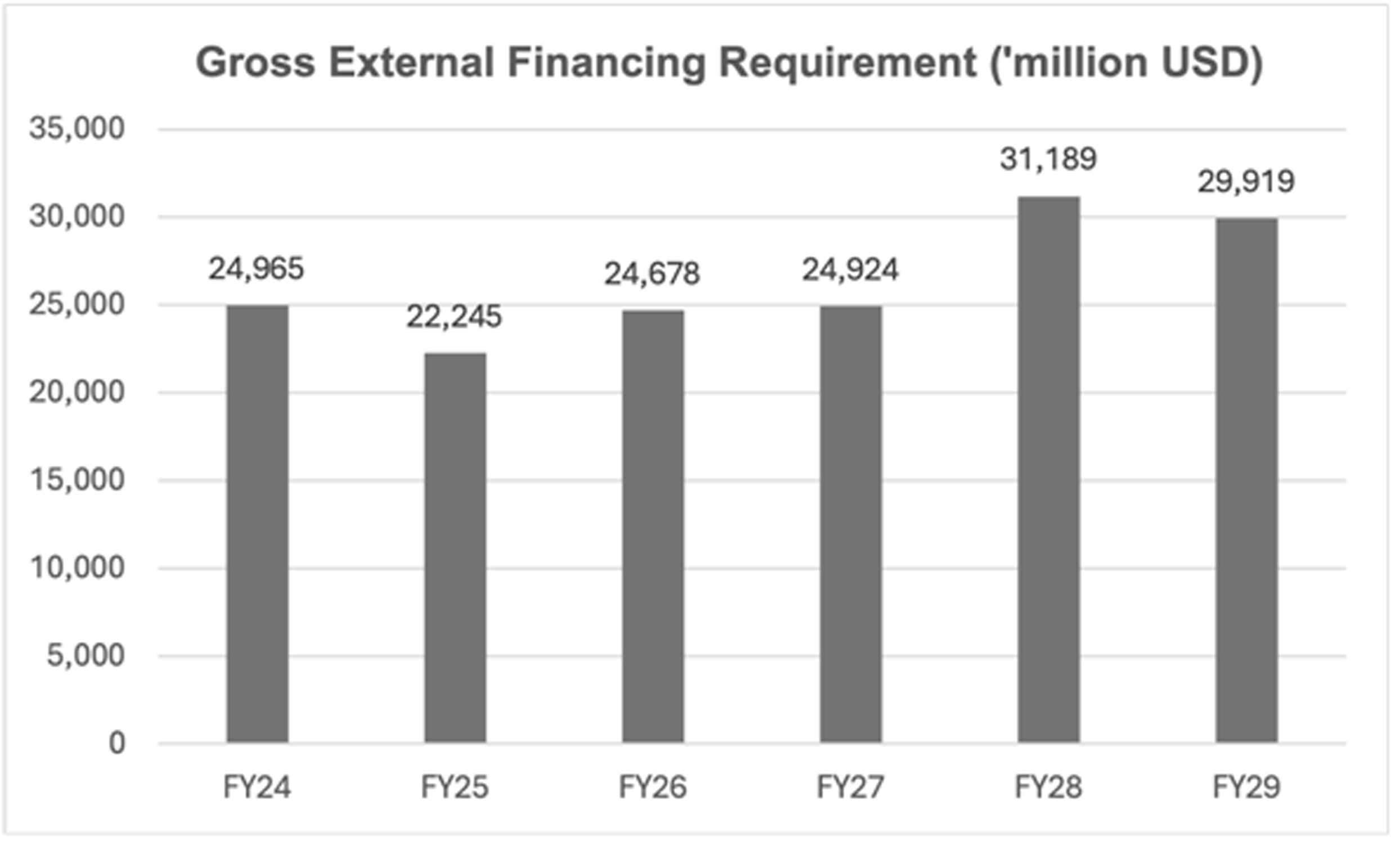

Pakistan’s external financing need has also been thoroughly covered in the latest IMF 1st review under the Standby Arrangement. While we have an idea for what amount of dollars Pakistan will need to conclude this year, as shared by the State Bank. Based on various growth and repayment indicators, the IMF predicts Pakistan’s external financing requirements for the upcoming years as follows:

Source: IMF review

As a percentage of GDP, Pakistan requires an average >6% of its GDP to only meet its external financing needs. While analysing the external account of Pakistan, the IMF staff commentary states that, “Pakistan’s external debt is predominantly to bilateral and multilateral creditors. Although the maturity structure is set to lengthen over the projection horizon, the high share of short-term debt poses risks to debt sustainability and will require timely disbursements from these creditors.”

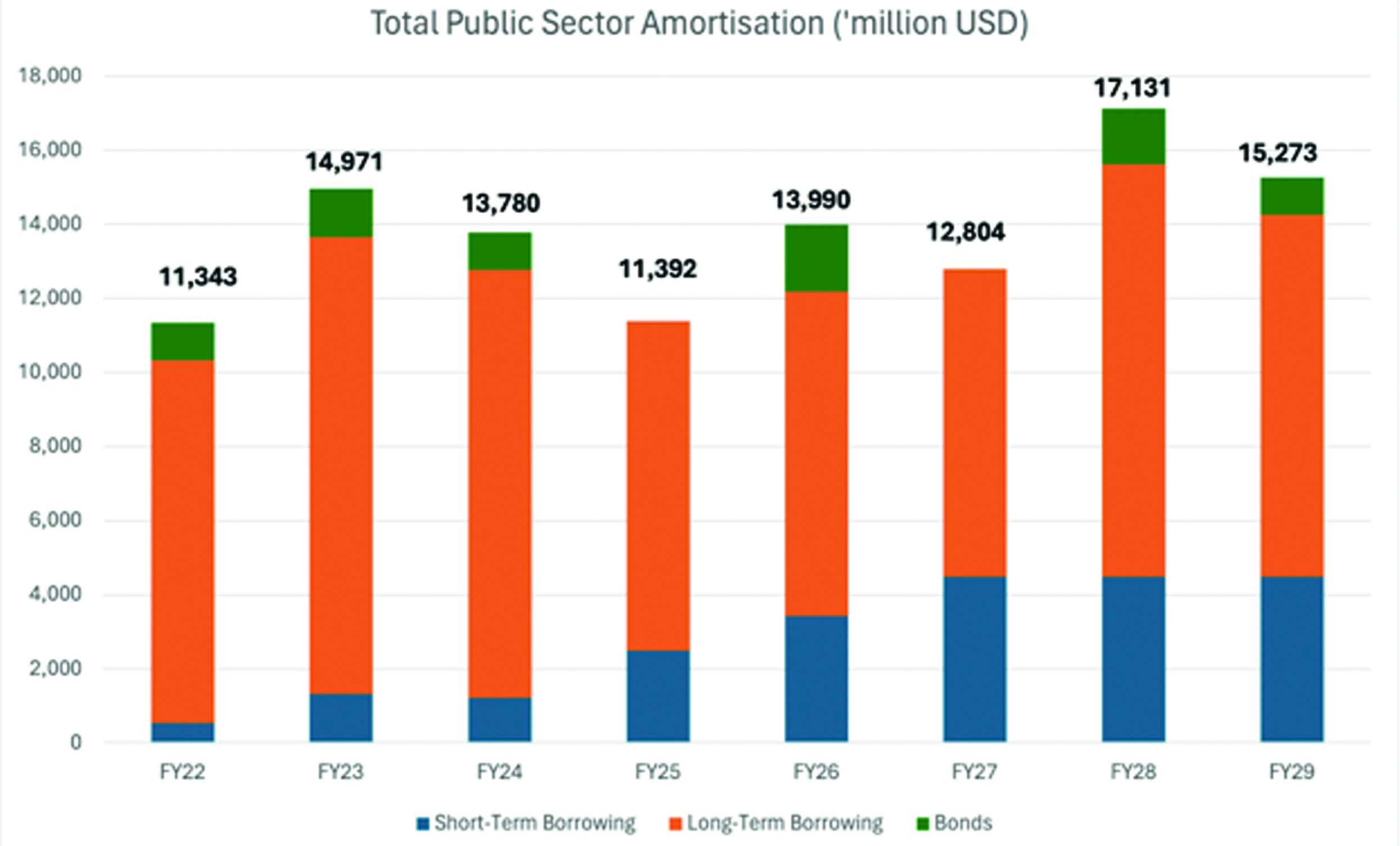

Following is the schedule of projected amortisations of Pakistan’s public sector debt. It can be seen that the short term debt obligations increase periodically over the next 4 financial years, causing repayment concerns. Moreover, as mentioned in the earlier SBP briefing, Pakistan is looking to roll over, not just a significant portion of this year’s obligation, but expects similar facilities from bilateral partners in the coming years. That increases the amount of amortisation for the subsequent year, and also raises interest payment significantly.

Source: IMF review

Since the IMF report is for the end of September 2023, as the year progresses, it becomes clearer that the graph above presents an optimistic picture of the economy. The IMF estimates come from a rather miserly estimate of the current account deficit, based on a controlled import regime during the PDM-led government. This move might not prove to be sustainable provided that Pakistan will have to let the imports flow once the manufacturing market equilibrium is restored. Pakistan might hold off on it for this year, but shrinking the size of trade up until 2028 would raise a completely different kind of problem.

Another reason why the external debt outlook is grim is because Pakistan currently stands at its historically highest ever level of external debt. Even after an optimistic IMF estimate, the figure is expected to go up, almost 10% faster than the GDP growth itself, increasing Pakistan’s debt to GDP ratio above 80%.

It is important to note that these projections are done on the basis of some crucial assumptions; that current account numbers remain optimistic, and that Pakistan gets into another long term IMF program and that all its bilateral and multilateral creditors extend their full support in the form of rollovers and program loans in the coming years. The report also assumes a Foreign Direct Investment number in excess of $1.5 billion owing to privatisation receipts that have been ensured by the current caretaker government.

External Debt projections

Even though the IMF finds some respite in Pakistan’s ability to secure high amounts of short-term loan, project loans, and other funds, one thing that still remains questionable is the sustainability of this “financing”. After all this is also borrowed money and comes with a deadline. In fact, the IMF projects Pakistan’s total external debt and liabilities at $147.7 billion by FY28, 20% higher than the current level.

A recent report by Tabadlab, an Islamabad-based think-tank, points out this pattern calling it “a raging fire” in their latest report. Ammar H. Khan, an independent economic analyst and the lead author of this report states that, “We are essentially stuck in a low-growth trap, with our reliance on import-financed consumption oriented growth not working anymore. Perpetual fiscal deficits will keep fueling more inflation, as the sovereign continues to borrow to bridge its deficits. To grow at 4%+ annually, we need incremental debt of $15bn+ every year. This can’t go on for long, till we re-tool the economy from consumption oriented, to investment, and export oriented growth.”

CAD management:

The amortisation of debt, however, is just one aspect of the external account. The developed world does not rely on external finance, but rather its own current account to meet its forex needs. The simplest way to do it is by increasing revenue (Exports, remittances etc).

Over the last two years, Pakistan has been able to manage its current account deficit, by controlling imports. This ensures low volatility in currency value and subsides a balance of payments crises. However, as a result of quashed imports, the exports have not been able to grow even to their 2021 levels. While this is seen as a standard response under an economic slowdown of 2022-23, the IMF expects Pakistan to fall back to its older importing habits once some stability is restored. As of now Pakistan’s cumulative imports for the first half of FY24 is $25.25 billion, an amount considerably lower than the IMF projections.

Recently the IMF asked Pakistan to increase the imports by 45% for the disbursement of its final tranche. The fund is expected to maintain its liberalised imports stance, for any future programs. As per estimates, Pakistan badly needs to be in an IMF program to be able to meet its financing needs, not just from the funds but by its bilateral partners. Failure to comply with any condition set forth by the fund could hence put a dent in these already bad numbers.

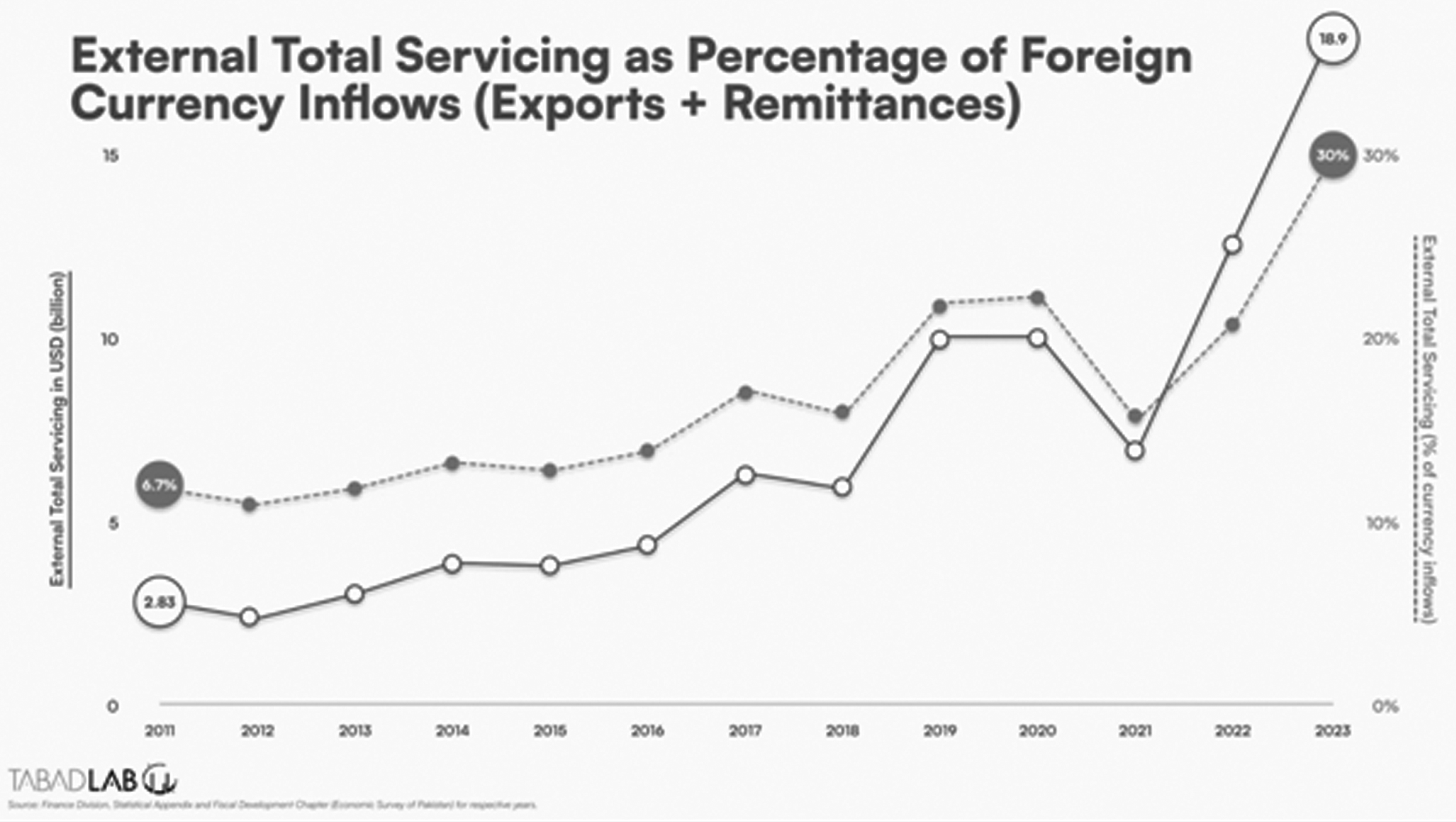

The only way out of the “Raging Fire,” as mentioned in the Tabadlab Report, is to boost the country’s income potential. A graph from the aforementioned report clearly shows how Pakistan’s forex inflows have become insufficient for even paying off the external debt requirements. The requirements that are expected to rise meteorically, as discussed above.

The task of controlling the balance of payments through the current account may seem tedious but right now it stands as Pakistan’s most viable option.

Is a restructuring on the cards?

Another possible way of solving this crisis is by restructuring debts. This would offset Pakistan’s public amortisations to a point in the future, allowing for more breathing space in the coming years. However, restructuring external debts is not as easy as restructuring domestic debts. It is important to note that domestic debt restructuring itself is no piece of cake.

Sovereign debt restructuring is a multifaceted process involving a government’s plea to lenders for principal reduction, lowered debt servicing costs, or extended maturity dates. If such a scenario were ever to emerge in Pakistan, this process will be initiated by the economic advisory committee and cabinet, conducted discreetly to prevent market disruptions.

Lenders typically seek exemption from restructuring, and the country must carefully assess its future repayment capacity under revised terms.

If one is to look at sovereign debt restructuring, it can be categorised into three kinds as a policy measure; Strictly Preemptive, Weakly Preemptive (likely for Pakistan), and Disorderly Default.

The process itself consists of initiation, negotiation, and implementation stages, with the government seeking assistance from the IMF for a Debt Sustainability Analysis in the initiation phase.

Negotiations then take place with major creditors such as the Paris Club, World Bank, China, Saudi Arabia, and commercial creditors, with the guidance of established bilateral frameworks like the G20 Common Framework. During this stage, all creditors must be offered comparable treatment as urged by the G20’s framework, and a committee of creditors is also formed. Lastly, implementation of the restructuring process can take time, 2 years and counting for example, in Zambia’s case. During this time, multilateral institutions like the IMF may provide additional financing to keep the country afloat. However, multilateral creditors are generally given preferred creditor status and are not a part of the restructuring arrangements.

However, past commentary by the finance division states that Pakistan might not be looking at the option. As per the Finance Minister’s media interaction at the end of last year, the majority of Pakistan’s external debt, 44%, is held by multilateral agencies and cannot be reprofiled due to their “preferred creditor” status.

Commercial debt makes up 14% of the external debt, and restructuring this portion is challenging due to the involvement of numerous stakeholders and a cumbersome process. Bilateral debt represents 35% of the external debt, and the government has already benefited from the payment moratorium G-20 debt relief initiative following the COVID-19 pandemic.

This means that while restructuring is one option, it is not being looked at as the go to option for Pakistan’s external debt.

The calm before the storm?

As the caretaker government steps out of the office claiming to have effectively managed Pakistan’s debt portfolio, the country enters a highly crucial phase of economic management. A latest Bloomberg report confirms Pakistan’s need for a long-term IMF program, worth $6 billion, once the elected government comes into office.

The economy, and in extension the external account, requires extreme management in the next 5 years with an adequate finance minister that salvages the growth potential while navigating the challenges.

Only a messiah well-poised and disconcerted from political point-scoring can now steer Pakistan out of this upcoming storm. A person well-versed in fiscal consolidation and well reputed at the IMF, if Pakistan were to enter, and carry out another IMF program.

While we do not have the name for who this messiah is likely to be, a majority of Pakistan stands clear on who it should not be. As put by former finance minister Miftah Ismail in a podcast interview, the ideal candidate for the finance minister seat is ABD (Anyone but Dar).

kindly correct the mistake in the this below mentioned paragraph the PMLN came to power in 2013 not 2023.

“The PML N government when they came to office in 2023, did not have an ideal environment, yet the international market had recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and Ishaq Dar, with the right mix of borrowing and spending, could steer Pakistan in a better direction. Dar’s immediate priority became securing loans from multiple bilateral partners who obliged.

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTOS FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE. I had lost over $152,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about, GEO COORDINATES HACKER. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 27hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. To anyone looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact GEO COORDINATES HACKER. I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact GEO COORDINATES HACKER. By usingEmail: geovcoordinateshacker@proton.mewebsite; https://geovcoordinateshac.wixsite.com/geo-coordinates-hack

Thanks for sharing more articles!! good luck

This article is good but explaining the debt for Pakistan is quite complicated. You need to mention how much bond,foreign country debt plus different debts do we owe to external creditors. We need charts to explain this. only then we can find solutions

Pakistan needs to sell its asset that are causing loses now is the time to sell assets like PIA etc otherwise we will suffer more.