It is 2024, and Pakistan’s government is on a mission to Marie Kondo its possessions.

On the advice of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the government is attempting to privatise at least 25 state-owned companies. Why? The fund believes this will help tighten the belt on spending and kickstart the economy. On the chopping block are some national institutions, perhaps the most famous case study being Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). But there are other storied national companies that are undergoing a massive change.

Take the example of the First Women Bank Limited. Founded in 1989 by Benazir Bhutto, the FWBL was meant to be a haven for Pakistani women looking for financial independence, and a way to increase financial inclusion in the country. But over its 35 year journey, the bank has at times faltered and this would not be the government’s first attempt to sell it. So what is the deal this time and how will this attempt be different?

The foundations of FWBL

The First Women Bank Limited was set up on November 21, 1989 by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, the first woman to become head of government of a Muslim-majority nation, with much fanfare. “Let the Women’s Bank be a pioneer in helping Muslim women secure economic independence and career satisfaction, within the cultural ambiance and social values of an Islamic society.” she said, at the bank’s commencement on December 2.

Cultural pandering aside, there was always a need for an institution like FWBL in Pakistan. Pakistan has one of the largest unbanked female populations in the world. Currently, if you are a woman in Pakistan and have a bank account that makes you part of only 39% of the female population that has access to formal banking facilities. And that is according to a very loose definition of “banked” set by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). The SBP is counting women that have signed up for digital wallets such as JazzCash and Easypaisa.

They are also conveniently not taking into consideration data that shows the patterns of how these female participants in the formal economy behave. In December 2022, only 62 lakh women in Pakistan owned debit cards, accounting for only 19% of debit cards in the country. Put another way, only 36.2% of the scheduled banking accounts of women had a debit card, compared to 55.3%c for males. So even when women have a proper bank account — not a digital wallet — they are far less likely to get something as basic as a debit card. And according to a 2023 report, while the SBP might claim 39% of women in Pakistan are banked, the World Bank puts this figure closer to 11.5%.

And these are numbers that have risen over the past four years, a time in which the central bank to their credit has pushed for female financial inclusion. In 2020, the SBP’s estimate of the banked female population was an embarrassing 17% compared to the South Asian regional average of 64%. In 2008, that number stood at a paltry 8%.

One needs to understand that the FWBl was an entirely different machine in 1989. This was a time when women had not joined the white-collar workforce in the numbers they have now and banking institutions were weak. As such, the goal was to provide as much access to capital as possible for the average woman.

The FWBL quickly got to work. The premise of the bank was simple: it would cater to women at all levels of economic activity, including micro, small, medium and corporate. It was the first commercial bank to launch microcredit in Pakistan.

The bank’s credit lending policies encouraged asset ownership among women as it lent to institutions, where women held 50% shareholding, women were the managing director or women made up more than 50% of the employees.

FWBL was set up with an initial paid-up capital of Rs. 10 crores, where 90% of the capital was provided by five banks namely, the National Bank of Pakistan, Habib Bank Limited, MCB Bank Limited (formerly: Muslim Commercial Bank), United Bank Limited, and Allied Bank Limited, all of which were state-owned at the time; while the rest of the 10% were provided by the federal government of Pakistan.

As of today, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) holds about 82.64% stake in the bank, whereas, HBL and MCB both have a 5.78% stake each, ABL has 1.94%, and NBP and UBL both possess 1.93% each.

Promises vs. Reality

The bank commenced its operations in 1989 with five branches spread across the country, rapidly expanding to 23 in a span of four years. However, after that, the bank only managed to increase its count to 38 branches until 2010, and now as of 2023, the bank operates only 42 branches across 24 cities of Pakistan.

It is conspicuous that women in Pakistan are desperate for access to credit and formal financial services even today. Only one percent of the women in Pakistan have the resources to start new ventures, this represents the stark gender disparity in the entrepreneurship domain of the country.

Furthermore, there is a humongous gap between men and women who hold a financial institution account. As we’ve mentioned earlier, women make up only 4.9 crores of the total 17.7 crore accounts in the country. However, only 2.9 crore individual women, or 43% of the female adult population, are associated with these 4.9 crore accounts. Admittedly, while these numbers are low, they have been worse. Adult female account ownership stood at 4% in 2008 and 18% in 2020, but it has increased to 43% as of 2023.

A more granular look into the data reveals that 3.23 crores out of these 4.9 crore accounts belong to the segment of branchless banking, which is provided by digital mobile wallets like JazzCash and Easypaisa. However, such wallets only provide limited financial services. This indicates that although Pakistan has made progress towards establishing a pluralistic system cognizant of the financial needs of women but far from reaching its goal. These historical numbers make the abysmal performance of FWBL apparent.

Most of the women entered the financial system in recent years with the help of SBP’s policy interventions like Banking on Equality and the growing footprint of digital mobile wallets rather than the initiatives of FWBL.

Therefore, in 2016, FWBL diverged from its original philosophy and reformulated its strategy by adopting an inclusive approach that embraced both men and women. They not only commenced serving men but also appointed them to senior management positions.

The bank’s inability to fulfil its objective of women empowerment, while remaining profitable compelled it to reorient itself. This rearrangement assisted the bank in reducing its infection ratio, constraining its non-performing loans, and growing deposits to a certain extent but its revenue and net income worsened.

FWBL, an institution with an ingenious vision that had monumental potential to enhance the status of women across the domains of commerce and entrepreneurship failed to live up to its expectations. It could have become a globally renowned bank for women and expanded to regions like the Middle East and Central Asia, but it wasn’t meant to be. The bank is now in shambles, as revealed by its financials, and left at the mercy of the privatisation commission.

“The fragmented research conducted by the First Women Bank Limited on the female market segment limited its effectiveness in incentivizing women to utilise its financial services and mobilise funds for women-led ventures in Pakistan. As a result, it underperformed and did not fully achieve its goal of financial inclusion of women in Pakistan,” remarked Naveen Ahmed, an investment banking professional based out of Karachi.

Financial rollercoaster

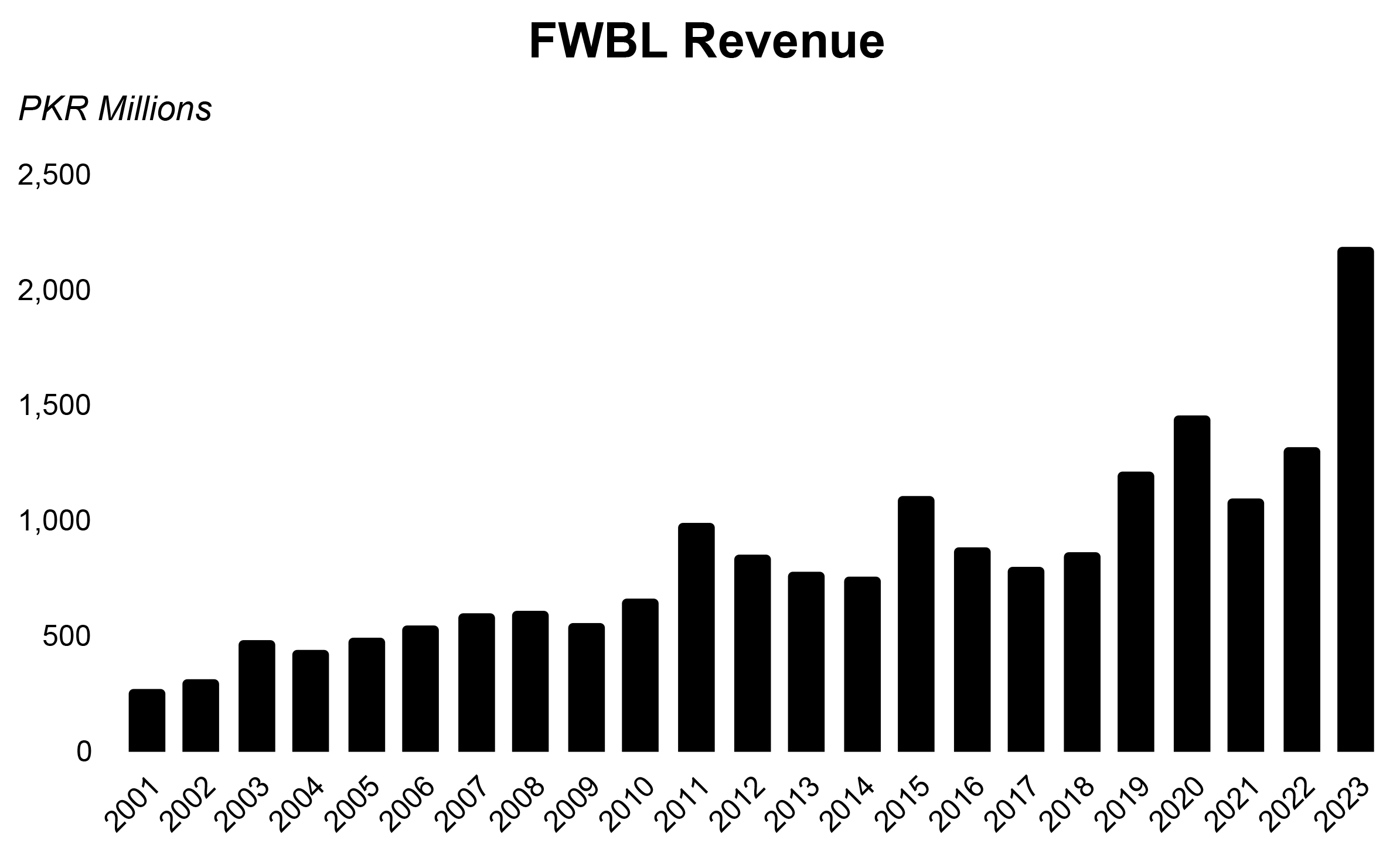

In 1993, the FWBL was lauded by the international media in 1993 with the headline “Pakistan’s Profitable First Women’s Bank Carves New Niche” and it performed decently throughout the decade of the 2000s. We analysed the financials of the bank from 2001 to 2023. FWBL achieved a revenue of Rs. 26.7 crores in 2001, which increased to Rs. 99.6 crores in 2011, growing at a rate of 14.1%, primarily due to its great outreach to female borrowers in rural areas. Approximately, 76.7% of FWBL borrowers were females from the micro credit segment. This impressive outreach became possible only because of the cooperation of NGOs and mobile credit officers in rural areas.

However, gross advances of the bank failed to keep up pace as they only grew at a rate of 4.3% from 2011 to 2021 in comparison to 25.2% from 2001 to 2011. Furthermore, the declining interest rate exacerbated the situation for FWBL, the policy rate went from 13.5% in 2011 to only 5.75% in 2016. Hence, the bank’s revenue stagnated after 2011 and expanded at a snail’s pace to reach Rs. 109.2 crores by 2021. Nevertheless, the bank’s revenue increased once again and doubled to Rs. 218.5 crores in just two years primarily due to high interest rates in 2022 and 2023.

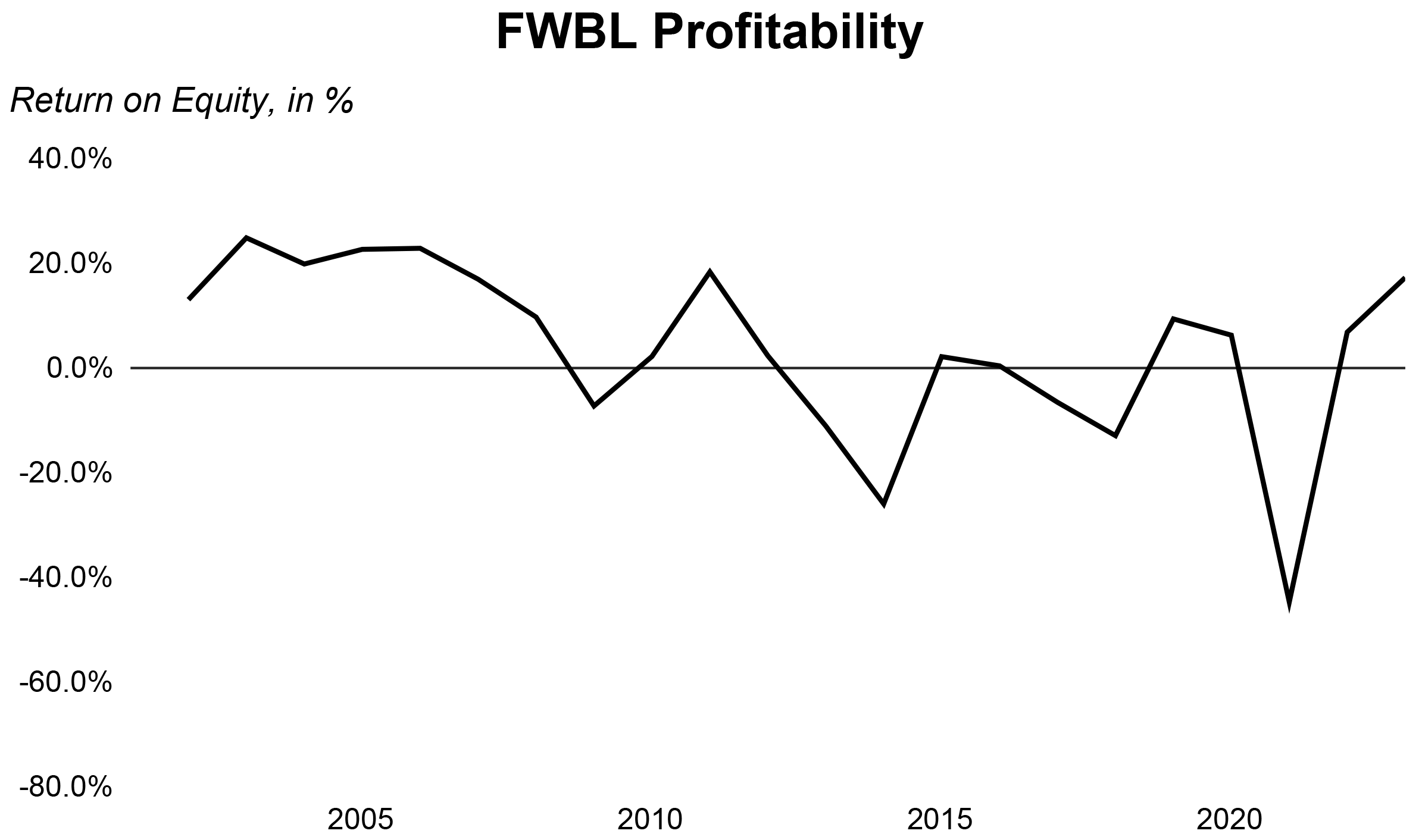

While inspecting the profitability of the bank, measured through return on equity (ROE), it is clear that the bank had satisfactory profitability ratios during the epoch of 2000s, where the highest rate was observed at 24.8% in 2003, while the lowest rate stood at -7.3% in 2009. After 2011, the bank’s ROE started to dwindle and reached negative territory. There were two primary reasons for this, firstly, the non-performing loans of the bank shot up significantly. They went from Rs. 52.3 crores in 2011 to Rs. 1.99 crore in 2018. The bank, adhering to its objective of women empowerment, continued to advance loans to females with limited credit history.

Along with this, lending to customers with political influence drove up non-performing loans. Secondly, the banks’ margins were slashed considerably, as the SBP cut the width of the interest rate corridor in a low interest rate environment. This resulted in banking spread falling to multi-year lows adversely impacting the markup income of FWBL. However, the bank made a brief comeback in 2019 and 2020 as its ROE turned positive before crumbling to its lowest point of -44.7% in 2021. The bank’s profitability improved once again, delivering an ROE of 6.8% in 2022 and 17.2% in 2023, respectively. This improvement was driven by strengthened net interest income and reduced non-essential expenses.

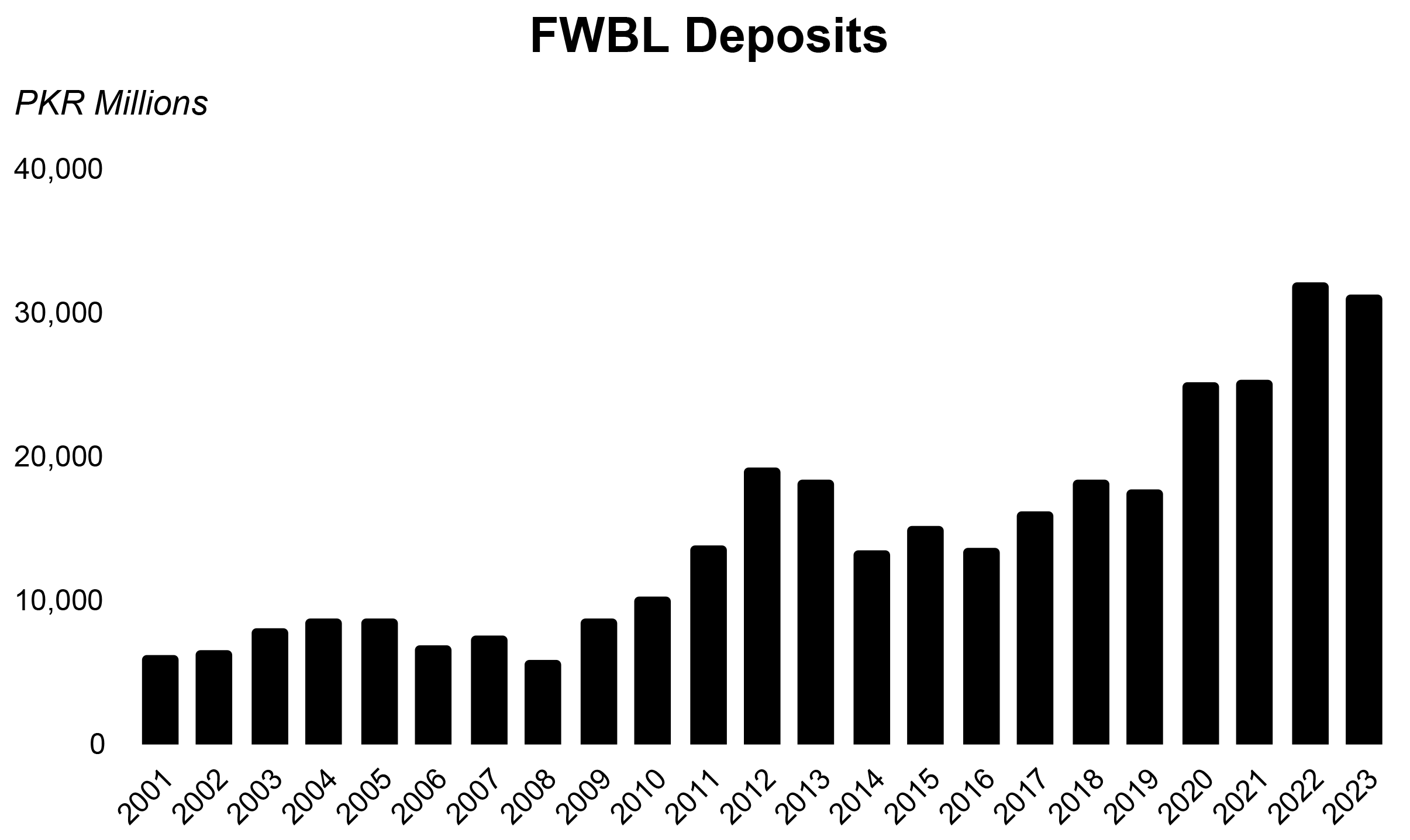

Another important metric incorporated into the analysis was deposits, which represent the trust of the customers in the bank. The bank racked up deposits from 2001 to 2012, as they increased from Rs. 616.7 crores to Rs 1919.3 crores (Rs 19.19 billion) at a rate of 10.9%.

However, as technology advanced and financial inclusion of women improved in Pakistan, competition for the deposits of women intensified. FWBL simply failed to distinguish itself from other traditional or modern digital banks with top-notch services. Hence, the bank’s deposits declined at a rate of 1.1% to Rs. 17,71 billion in 2019.

Further, interest rates in Pakistan have remained elevated since 2019 for the majority of the time, which has encouraged customers to deposit money in savings accounts, leading to a surge in the bank’s deposits once again post-2019. The bank’s deposits expanded at a rate of 15.3% to reach an all-time high of Rs. 31.32 billion in December 2023.

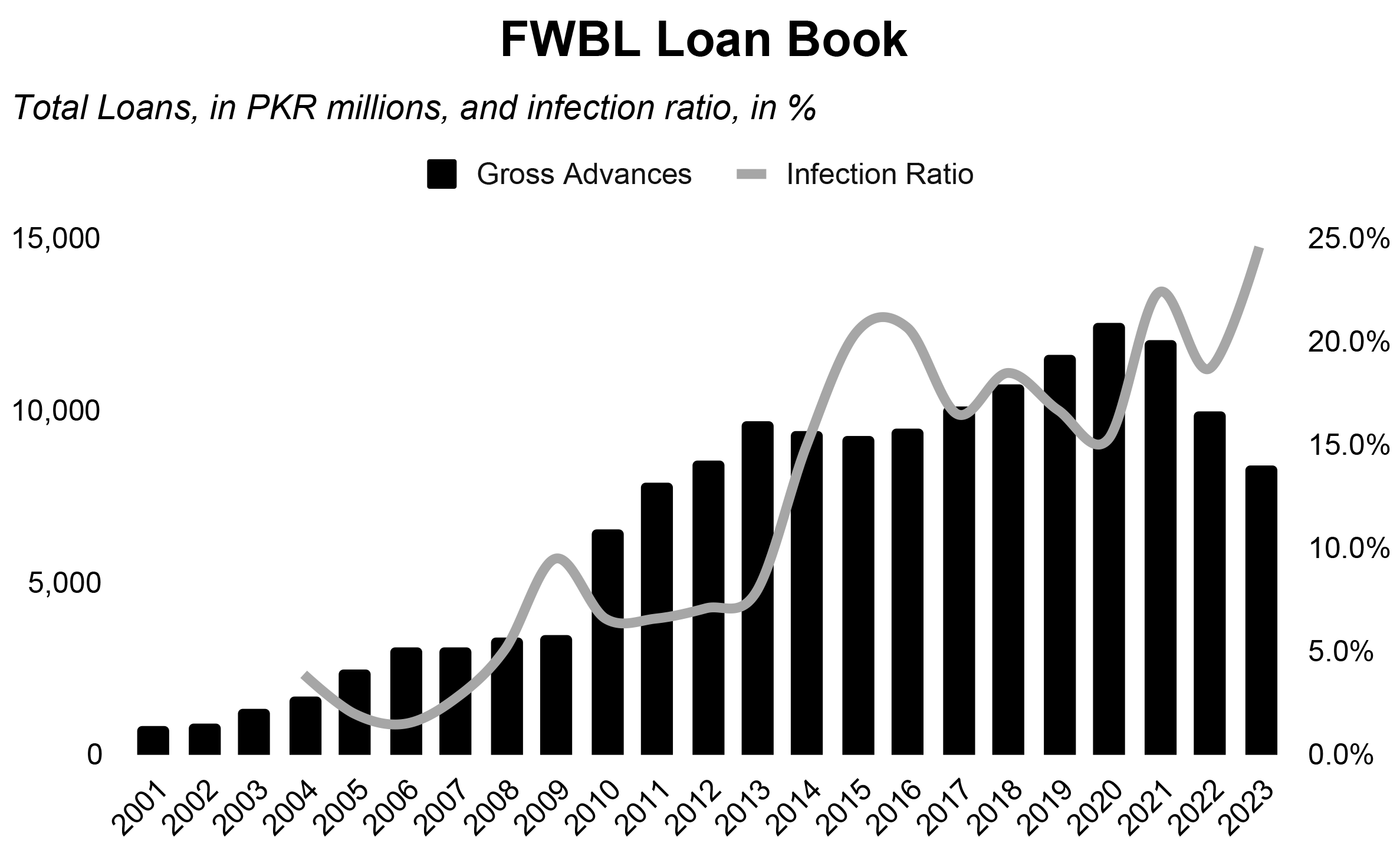

The First Women Bank’s gross advances continued its upward trajectory at a steady pace of 22.7% from 2001 to 2013, they went from Rs. 83.2 crores in 2001 to Rs. 966.9 crores in 2013. Afterwards, they ran out of steam and crept at a rate of 2.8% from 2013 to 2021 to reach Rs. 12.5 billion.

The First Women Bank’s gross advances continued its upward trajectory at a steady pace of 22.7% from 2001 to 2013, they went from Rs. 83.2 crores in 2001 to Rs. 966.9 crores in 2013. Afterwards, they ran out of steam and crept at a rate of 2.8% from 2013 to 2021 to reach Rs. 12.5 billion.

During 2022 and 2023, the bank’s gross advances contracted further and stood at Rs. 844 crores as of 2023. This was primarily driven by the diminished lending activity of the bank and the degraded credit risk in the bank’s portfolio, which created a tempestuous operating environment for the bank.

A trend evident in its infection ratio is that it has been increasing since 2006, but it remained below 10% until 2013, after which it escalated to 15% from 7.9% in a year. The situation deteriorated further in 2016 as its infection ratio increased to 20.7%. The banks’ infection ratio has remained above 15% ever since 2014, and currently sits at 24.6%, the highest in its twenty-year history.

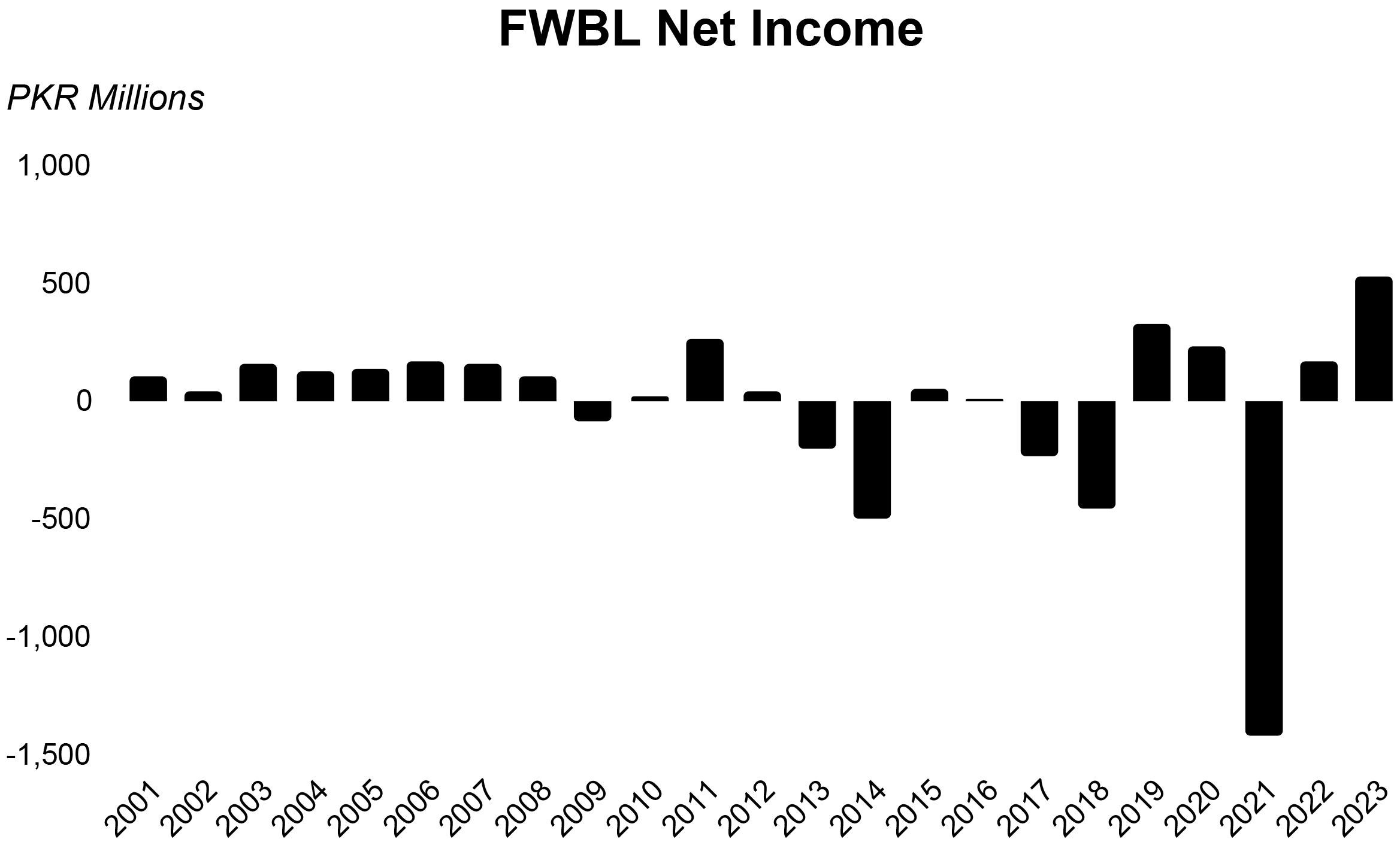

It is discernible from the financials of the bank that it maintained a healthy bottom line from 2001 to 2011, its net income increased from 10.1 crores in 2001 to 25.8 crores in 2011 at a rate of 9.9%. It is quite an impressive performance considering its clientele was limited to women-oriented enterprises.

It is discernible from the financials of the bank that it maintained a healthy bottom line from 2001 to 2011, its net income increased from 10.1 crores in 2001 to 25.8 crores in 2011 at a rate of 9.9%. It is quite an impressive performance considering its clientele was limited to women-oriented enterprises.

However, the bank’s net income plummeted after 2011, as it either incurred massive losses or remained marginally profitable until 2018. This was driven by a large stock of non-performing loans, a narrow spread, and modest growth in gross advances.

Acting President Naushaba Shahzad turned around the bank’s performance after 2018 through business development, product innovation, and enhancements in internet banking. Additionally, she established a 24×7 call centre and relocated several branches to augment the bank’s brand identity and amplify its visibility.

Although the strategy pivot in conjunction with a high interest rate environment ameliorated the financials of the bank during 2019 and 2020. However, this revival proved to be ephemeral and fizzled out as soon as the management changed and high interest rates left the scene. Afterwards, the bank’s capricious performance continued; it reported a loss of Rs. 141.6 crore in 2021, but posted a profit after tax of Rs. 16.8 crores and Rs. 52.3 crores in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

These profits were fundamentally generated by the bank’s investment in government securities, which not only prevented capital erosion but also provided stable returns.

Our perspicacious analysis reveals that all major metrics of the bank began moving south during 2011 and 2012 and continued to do so until 2018. FWBL’s revenue declined by 13.2%, deposits shrunk by 4.3%, net income plunged by 276.6%, return on equity contracted to -13.8% from 15.0%, and the infection ratio jumped from 6.6% to 18.5% during this period. This appalling performance of the bank persuaded the government to initiate the privatisation of FWBL in 2018.

Our perspicacious analysis reveals that all major metrics of the bank began moving south during 2011 and 2012 and continued to do so until 2018. FWBL’s revenue declined by 13.2%, deposits shrunk by 4.3%, net income plunged by 276.6%, return on equity contracted to -13.8% from 15.0%, and the infection ratio jumped from 6.6% to 18.5% during this period. This appalling performance of the bank persuaded the government to initiate the privatisation of FWBL in 2018.

The Road to FWBL’s Privatisation

Historically, various governments on multiple occasions have contemplated privatising the bank, particularly in the years 1994, 1996, and 2015, however, on October 31, 2018, the Cabinet Committee on Privatisation (CCoP) put FWBL on the Active Privatisation Programme, which was later sanctioned by the federal government on November 1, 2018. Hence, the Privatization Commission (PC) disseminated a Request for Proposals (RFP) on October 18, 2019 for technical and financial proposals.

Once the technical and financial evaluation of the bids concluded, the syndicate of MIS Bridge Factor & National Bank of Pakistan were chosen as the Financial Advisor for the privatisation transaction of the bank by PC on December 27, 2019. The Financial Advisory Services Agreement (FASA) was signed on January 27, 2020.

The due diligence report of FWBL was filed in June 2020 under the supervision of the Ministry of Privatization, while the Cabinet Committee on Privatisation approved the Transaction Structure on August 21, 2020. Nevertheless, due to the unavailability of audited accounts (FY 2018 to FY 2021) later steps could not be fulfilled such as Expression of Interest (EOI)/Request for Statement of Qualifications (RSOQ).

Although the FASA was signed for only two years, it was extended twice, first for another fifteen months till April 26, 2023, and then for another two years till April 25, 2025, as per the approval of PC.

The government of UAE communicated its interest in acquiring 82.64% shares of the federal government in FWBL through a formal agreement, congruent with relevant laws and regulations. The federal government has authorised the Privatisation Commission (Government-to-Government Agreement Mode, Manner, and Procedure) Rules, 2023, conducive for such transactions under the Inter-Governmental Commercial Transactions Act, 2022.

The financial advisor has commenced the valuation process for the government’s shares in FWBL utilising methodologies embedded in the above-mentioned rules. The federal cabinet approved the privatisation commission’s recommendations regarding FWBL, which are essential for scrutinising the UAE government’s proposal.

The following steps encompass instructing the Privatization Commission to move forward with the bidding process or referring the transaction to the Cabinet Committee for the constitution of a Negotiation Committee, ratification of the price discovery mechanism, and reference price, as per the Inter-Governmental Commercial Transactions Act, 2022, and associated rules.

“The government of Pakistan has historically believed that it is facilitating its citizens by operating businesses. However, government-led institutions like the First Women Bank Limited typically lack the incentive to maximise shareholder value. This results in an inefficient allocation of funds and resources, the burden of which is eventually borne by the taxpayers it intended to assist. Hence, the government should focus solely on acting as a regulator,” elaborated Yousuf Farooq, Head of Research at Chase Securities.

What’s ahead?

Although the government of Pakistan has ventured out numerous times to privatise FWBL, it has never been able fulfil the task at hand because of no compulsion urging the government to offload the bank.

However, this time the circumstances are a bit different, the government has been obligated by the IMF to abandon numerous SOEs, including FWBL, to abate its fiscal deficit. The government complying with the demands of the IMF has expressed its determination to expedite privatisation by unveiling a five-year Privatisation Program 2024-2029.

As per the program, FWBL is supposed to be privatised by the end of fiscal year 2025, which appears to be more likely than ever as the government finds itself in a tight spot with no other viable options. The sooner this white elephant is sold to a well-reputed investor, the better it will be for all stakeholders, including the government, the bank, and the taxpayers.