It is somewhat ironic that one of the best known political satire plays in Pakistan is called Taleem-e-Balighan, set at an adult literacy center in the 1950s. Such centers existed in many parts of Pakistan and were meant to increase the then-abysmal literacy levels in the country, but had almost no meaningful impact on the country’s literacy rate.

If one even tries to talk about Pakistan’s population as an asset, as this newspaper did two weeks ago, the first thing one gets hit with is: “yes, but the people aren’t educated, so they are still a liability.” That illiterate people are economically a liability is not quite accurate, but even leaving that quibble aside, Pakistanis view of just how much progress we have made in improving literacy and education levels in our population is at least partly outdated.

This article is the third in our “optimism about Pakistan’s future” series, and in this one, we will make it a point to concede to the pessimists: they are correct in noting that the state of education in Pakistan is not good, and it is not improving at a rapid enough pace for us as a nation to be satisfied with. What we will argue, however, is that what we have achieved thus far – and what we are on track to achieve over the next decade – might be “good enough” to achieve industrialization.

We can summarise the analysis of Pakistan’s education sector in the following way:

- Pakistan lags behind not just developed countries, and the East Asian tigers but also its own regional peers and is uniquely bad in terms of any educational metric across any grouping of countries that could reasonably be described as Pakistan’s peers.

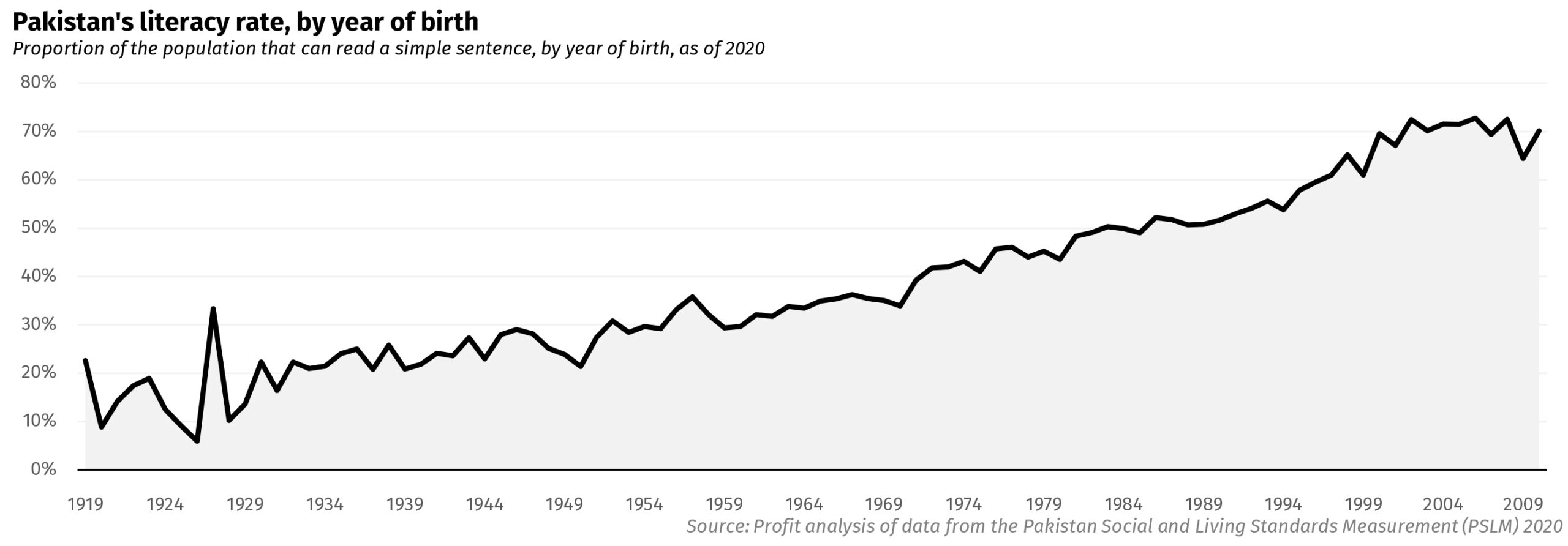

- Despite woefully inadequate management of the sector, the country has managed to make significant progress in improving literacy and numeracy: the literacy rate among children born in any given year has continued to rise almost uninterrupted over the past several decades.

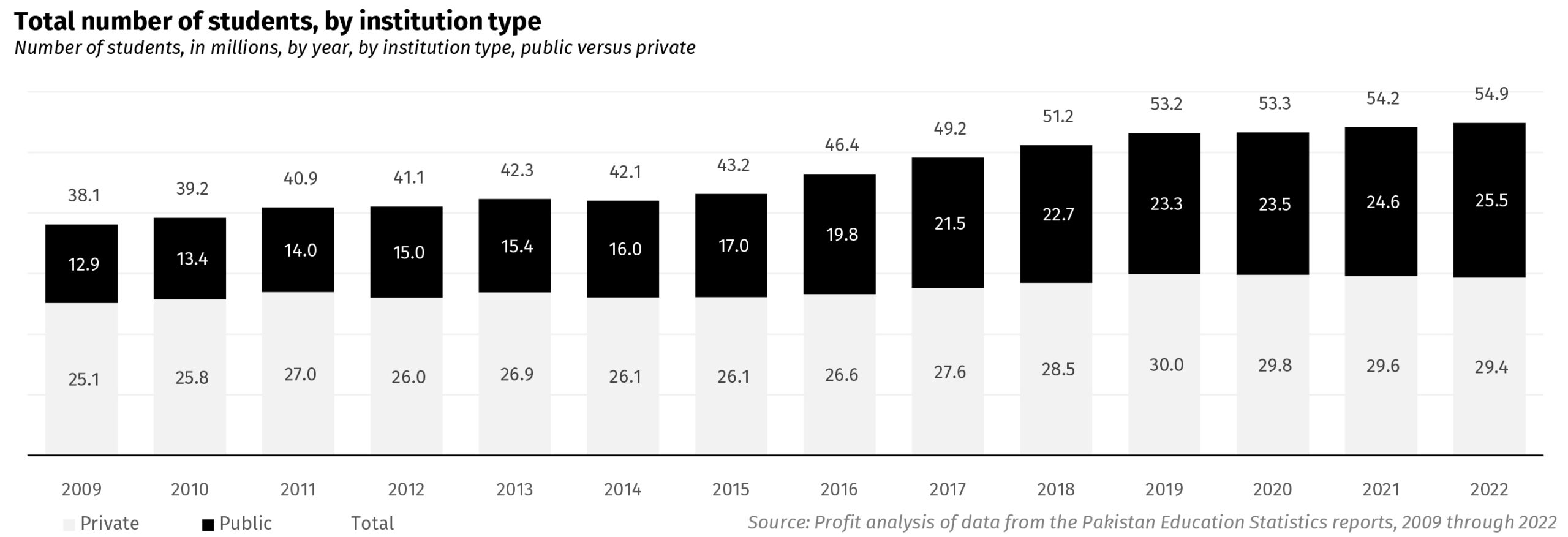

- While the government has made some progress in improving the quality of public education, the majority of the increase in Pakistan’s educational attainment levels has come from household incomes rising – and household sizes falling – to a point where private education became a more viable option for more families.

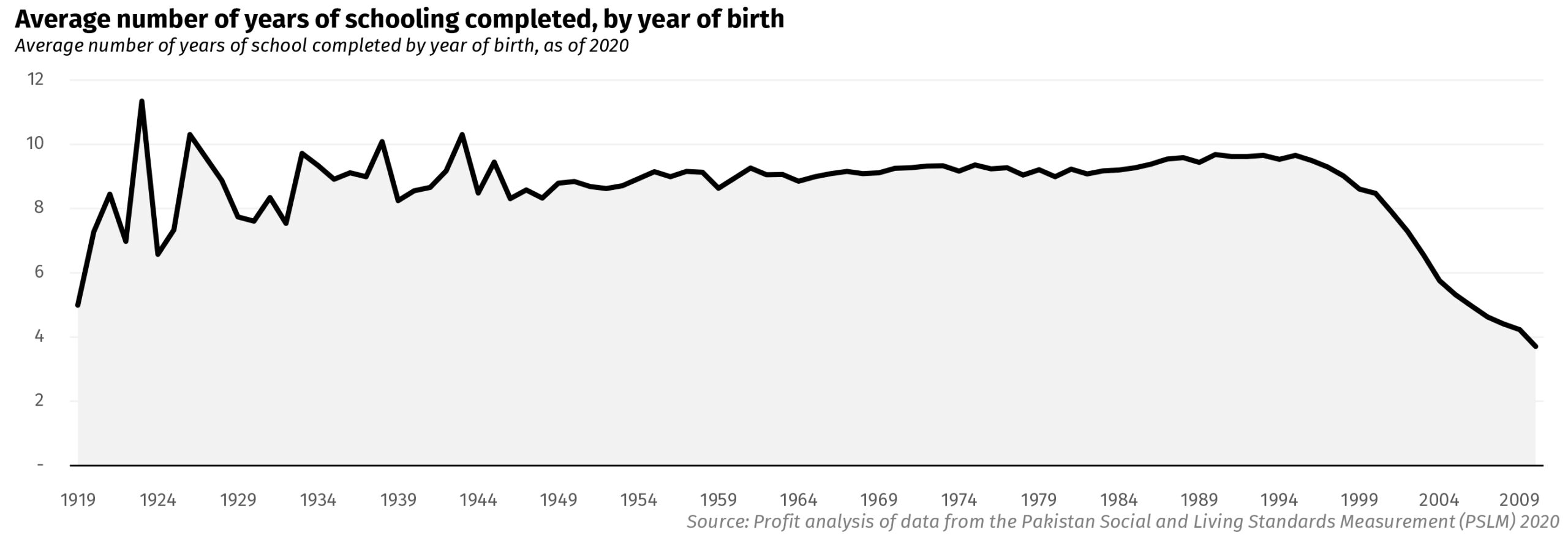

- Overall educational attainment levels – measured in the number of years of schooling completed per student – are rising, but very slowly.

- Economic research indicates that adult literacy rates exceeding 70% are required to begin industrializing (along with several other factors, which we have and will discuss in other articles); and while Pakistan is not quite there overall, it has already hit that level in its urban areas, and will likely hit that level nationally some time over the course of the next decade and a half.

For this story, the data we analysed was taken from the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey (PSLM), published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the latest of which was the one for the year 2020, and the Pakistan Education Statistics reports put out by the Pakistan Institute of Education.

In this article, we will not spend a lot of time explaining just how far behind Pakistan is relative to its regional peers. That story has been told better by others. Instead, we want to focus on a part of the story that rarely ever gets told: what is Pakistan’s rate of improvement, and are we doing enough to progress as a nation?

Patchy progress, but clear upward trajectory

First, the good news: every successive generation of children is better educated than the generations before them, and the progress is by and large steady enough that it is measurable from year to year: children born in 2006, for example, were more likely to grow up to become literate than children born in 2005, and so on. Across both urban and rural areas, Pakistan is now able to consistently educate at least 70% of its children to be literate and numerate.

This is a significant improvement over the past several decades. As recently as the 1990s, a literate person in Pakistan was not only part of the minority of the country, but so completely surrounded by illiterate people that it was hard to escape the fact that to be literate meant to be a fortunate minority in Pakistan. Now, it is possible to go several days without encountering an illiterate person under the age of 30 in urban areas in Pakistan.

The patterns for how this progress has happened have been reported elsewhere, but nonetheless bear repeating: men are much more likely to be literate than women (70% of men, and 49% of women, as of 2020); residents of urban areas much more than rural areas (74% urban literacy versus 52% rural literacy), and the young are more literate than older adults (72% for the youth between the ages of 15 and 24 compared to 57% for the overall adult population).

Young men in cities in Pakistan are approaching close to universal literacy and numeracy (85% across Pakistan). Optimistically, the gender gap is narrowest among young people in cities (urban female youth literacy is 82% across the country).

All of this points to a simple fact: anyone in Pakistan who can get educated chooses to do so. The lack of education appears largely a question of access, not willingness. For all the popular culture references to useless degrees, revealed preference indicates that Pakistanis firmly believe that education itself, and educational credentials in particular, carry value.

Implied in the above picture, however, is a bit of bad news, to which we alluded at the beginning of this article: adult literacy efforts in Pakistan are effectively non-existent. If a Pakistani reaches the age of 18 and has not learned to read or write, they probably never will.

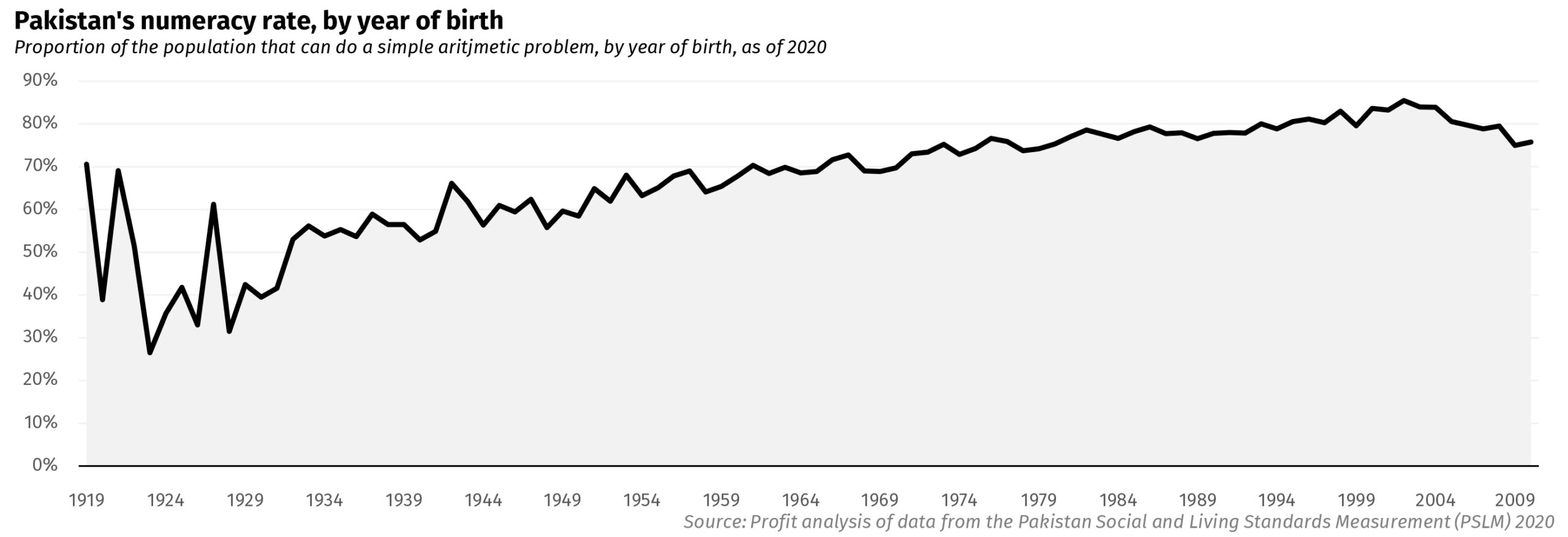

Interestingly enough, however, there is a significant number of Pakistanis who never learned to read and write, but over the course of their adult lives learned to do just enough basic mathematics that, when asked by a surveyor, can correct perform basic arithmetic sums without a calculator. This is not a small population, either. By our estimates using PBS data, we think that as many as 25% of Pakistani adults can be characterized as illiterate, but sufficiently numerate.

This makes sense if you give it some thought: you may have met several illiterate people this past week, but when was the last time you met an adult to whom you gave cash and they could not count how much you gave them or, more importantly, how much you need to give them?

Not waiting for government favours

While part of this progress is certainly driven by improvements to the government’s own infrastructure, measured purely by proportion of the increase in student enrollment, the private sector has contributed just under 75% of the total growth in enrollment between 2009 and 2022, according to enrollment estimates published in the Pakistan Education Statistics reports published by the Pakistan Institute of Education. The public sector accounts for the remaining 25%.

In other words, Pakistanis are not waiting around for the government to fix the schools (even though the government is making some progress on that front). They are simply going ahead and paying for private schools themselves as soon as they have the ability to pay.

This phenomenon helps explain why the fastest progress in terms of increasing literacy happened in the decade after Pakistan’s dependency ratios – the ratio of prime working age adults to the number of children under the age of 15 and retirees over the age of 65 – peaked.

The dependency ratio peaked in 1995, and that year also represented the an inflection point in literacy improvements: for every year after that, the 10-year progress towards improving literacy kept on rising at a rising pace (the second differential was positive) for the next decade.

What does that mean? It means that once families started to find that they had a bit more spare cash to spend (with dependency ratios declining after 1995), they started investing that spare cash into private school fees for their children, especially in urban areas, and especially in the urban areas they did so at nearly identical rates for their sons and daughters.

Having spent the lead up to 1995 being increasingly cash strapped, the first thing that Pakistani families did when the pressure on their cash flows eased a bit was to invest in the future economic productivity of their households by educating their children. And in perhaps a scathing indictment of how bad the public schools were, they did so through private schools even when public schools were available in their areas.

This increased investment led to the fastest expansion in literacy rates in Pakistani history. Children born in 2004 have a literacy rate of nearly 72%, which is a full 18 percentage points better than children born in 1994. That 18 percentage point increase took place over just 10 years, the fastest 10-year increase at any point in Pakistani history.

Since this increase became possible in large part due to the decline in fertility rates, and through the increased willingness to spend scarce household resources on private school fees and not the heavily subsidized private schools, we are led to the rather extraordinary conclusion that the government of Pakistan’s most effective contribution towards improving literacy in the country was not through the Education Departments of the provincial governments’ building and managing schools but rather through the Population Welfare Departments’ efforts to help with family planning.

Nonetheless, there do appear to be limits to how much improvement the country has been able to achieve over the past few decades in terms of educational attainment levels.

Stagnating attainment levels

While literacy has been improving relatively consistently, what has not improved by much is the quality and quantity of education made available to the median student in the country. Measured by the average number of years of schooling completed, there has been some progress to be sure in terms of the number of years a given student spends in the classroom, but this progress has been painstakingly slow.

The median Pakistani who attends school is able to at least get to Class 10 (Matric), and in a good year may even pass. The proportion who go on to higher levels has been rising somewhat, and the population of Pakistani college students has quadrupled in the last decade. But that proportion is not enough to have made a meaningful dent in the overall educational attainment levels of the country.

Matric being the point of highest drop-off from the schooling system is interesting: firstly, the fact that Class 10 is conducted across Pakistan’s education system like a terminal diploma program (the government issues an actual certificate for pass Matric that it does not for previous levels) makes it feel like a natural drop off point.

It is also a point that the median student achieves sometime after the age of 15, which is the age where the trade-off between continued schooling and entering the workforce as a literate young adult starts to become meaningful. And in another instance of revealed preference, it appears that the median Pakistani family believes in education enough that they feel the need to spend money to ensure that their children are literate and numerate, but investing beyond that level is not seen as being worth the cost of having a 15+ year old child of theirs continue to be a cost center rather than an income generator.

This is despite the fact that, post-Matric, the educational options available to Pakistani students start to become skewed towards public education, meaning it may actually end up being cheaper for a family to send their child to a post-Class 10 educational institution than the fees that they paid to get the child to the Matric level.

Despite two decades of rising private sector enrollment, two-thirds of Pakistani students who go on to Higher Secondary (Intermediate) education do so at government institutions. And nearly 85% of university students in Pakistan attend government universities. Both of these levels of education, at government institutions, are heavily subsidized, and yet these are also the levels that most students are choosing to not pursue.

The difference between “good”, and “good enough”

The picture of the education sector in Pakistan, therefore, is clearly a mixed bag. It is not as uniformly bad as the public conversation around it might have you believe: literacy rates are clearly rising across generations and our still-young population means that the effect of educated children on our adult literacy rates will likely be quite rapid.

On the other hand, it is abundantly clear that educational standards in Pakistan are so low that we do not even bother to compare outcomes in Pakistan to those of globally competitive economies, whether in our own region or further afield. And on this front, progress – though unmistakably occurring – has been far slower. We are getting more children into school but not really doing much to keep them in longer, or teaching them much better than in decades past.

In short, what we have in terms of education is certainly not good.

But is it “good enough”? What would even constitute “good enough”?

It is our contention that while Pakistan is unlikely to become the kind of country that leaps from third world to first in one generation, a la Singapore, we might be able to make decent progress towards at least second world status in one or two generations.

Pakistan’s educational attainment levels are clearly not enough to become a high-tech manufacturing hub, or even a large services economy. But have we done enough to at least start industrializing with basic and intermediate level industries? The answer to that question is: most likely, yes.

Economists who have studied early industrialization among major economies around the world have come to the conclusion that, while universal literacy would certainly be great to have, an economy at the earlier stage of its economic development can make do with as little as 70% adult literacy rates, a number that Charlie Robertson, economist at the London-based hedge fund FIM Partners, calculated for his book The Time Traveling Economist.

Pakistan is clearly short of that number, currently at close to 60% adult literacy rates. In urban areas, we are already past 70%, however, and in all of Pakistan 10 largest cities, adult literacy rates approach or exceed 80%.

The common retort to these statistics is: yes, but what good is basic literacy? Our response: good enough for our current stage of economic growth.

The median Pakistani worker does not need to compose a complicated report on macroeconomic trends in Pakistan’s trading partners, or write code for a new large language model (LLM). They need to be able to read enough to know that the clothes they just stitched at the textile factory they work at need to be placed in the box marked “Germany”, not the one marked “America”.

Is that level of skill and manufacturing how you build a globally competitive economy? No, but that is first step on the ladder to get from where we are right now to that globally competitive economy. In an ideal situation, we would have spent much more of our national resources on education and, far from being a byword for a biting satire on state failure, Taleem-e-Balighan would have referred to how Pakistan educated its people out of poverty.

But we are not that country, so we must make do with what we have. The attitude Pakistanis seem to have is that if the change will not have in one generation, it is not worth pursuing, and we would suggest that this is at least a two-generation project in any country not led by Lee Kwan Yew.

If you view Pakistan’s education system from the lens of the question: “is this coming generation of workers educated enough to compete with workers in America, Germany, or even Mexico?”, the answer you will arrive at is “no”. But if you ask the question: “is this coming generation of workers educated enough to start working at the kind of basic industries that will increase their incomes five-fold in one generation and allow them to afford to educate their children to become the generation that competes against the best in the world?”, the answer to that question might be “yes”.

(The lack of investment in education, by the way, is why Ayub Khan’s much-vaunted Second Five Year Plan failed. The South Koreans studied that plan and implemented many of its components, but added one crucial difference that the Ayub Khan Administration did not: an insistence that every single illiterate adult attend school at night to learn how to read and write.)

A retort to the above assertion that Pakistan’s catch-up economic growth will take longer might be that any goal is easier to achieve if you redefine it downwards. We would submit to you that even making steady progress towards achieving middle income country status would result in more uplift in the material wellbeing of Pakistanis than we have ever achieved in our history.

It is a goal “good enough” to ensure that our fellow citizens no longer live in abject poverty, even if it means that Dubai will continue to feel expensive to our upper middle class when they visit. More importantly, it is a goal “good enough” to not require our national leadership to spend their days dreaming up cockamamie schemes like CPEC or the next hare-brained idea to get the Americans to give Pakistan more money and instead focus on an endogenous engine of economic growth.

Now that may well be a goal that is not just good enough, but also just plain good.

Fully endorse your assessment.

Pakistan will be a major economic power by 2050, IA.

Its good to be optimistic, and realistically optimistic even more so. If being able to write you name in considered literate then the literacy rate should be close to 90% in Urban areas if not more. At the same time only 10% seem to be following the traffic rules as a basic metric and most will not be able to make it through the first paragraph of you article and decode, even after being translated to Urdu. Pakistan has a considerable number of PhDs, but not many are published in major journals or result in meaningful innovations. Justification for a large population drawing in remittances is also taking a hit, with ME countries complaining of low standards and high crime rates among the Pakistani expats. In my opinion the issue lies in the mindset, where there is general aversion to collective thinking, and in that scenario even high education levels cant do much. If only 50% of Urban women are educated, then that itself signifacntly reduces the first exposure of basic education as most women simply raise children rather than work. these children then get educated on the streets. Also analytical and critical thinking seem to be missing in the currciculm, and the idea is to just get hold of a degree, diploma, by memorization, hook or crook. On the other hand, perhaps the only goal of South Korean children and their parents, which was mentioned in your population article, is to make it to a “chaebol” company. Economies have transformed to knowledge economies and education from general to STEM. So in that sense again we lag far behind, as also in industrialzation which your article mentions requires 70% to be educated. True global Industrialzation began perhaps after WW1 and has rapidly progressed to the digital revoultion and now the AI/robotic/automation revoultion that we are now witnessing unfold. In essence, digitalization only acts as a support system for industrialzation. Without industrial there would not be much of a need for the digital. And if we are just beginning on the industrial as per your article then we are already a century behind compared to industrialzed economies. Nevertheless, the stastics are still a step forward and in the right direction, and on a self sustaining basis it would eventually help us. Much needs to be done at the grassroot level to improve the quality of our final product which itself takes atleast 20 years to produce. Optimism drives us forward, but at the same time its good to be realistically and cautiously optimisitic.

Calculadora Alicia: Tu Mejor Amiga para las Matemáticas