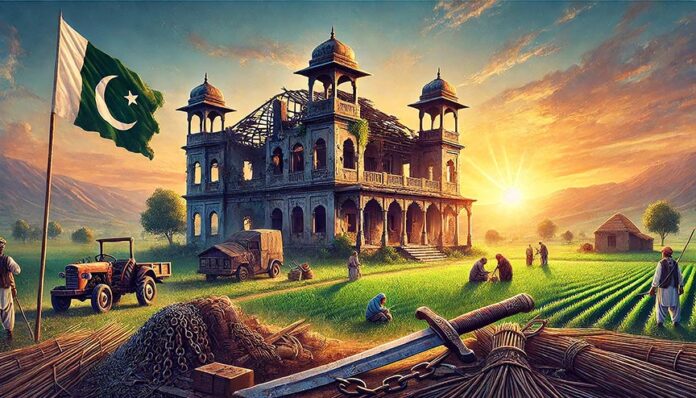

Sometime during the Musharraf Administration a very important economic milestone was crossed in Pakistan. Agricultural land ceased to be the largest asset class in Pakistan, a title that it had likely held for millennia before then. With that change died the economic basis of what had hitherto been one of the defining features of Pakistan’s political economy: feudalism.

It rarely gets mentioned now, but there was a time not very long ago when a discussion of Pakistani politics was almost impossible without mention of the word “feudalism”. It was to pre-2008 opinion journalism what “civ-mil” is today: the topic everyone discusses ad nauseum and talks about as the permanent feature of the country’s political firmament.

But contrary to one of the most fervently held of Pakistani beliefs, things do change in Pakistan, and they change rather dramatically at times, albeit not always at the pace the population would hope they would. No doubt some will consider the title of this article to be provocative, but once we are done laying out the evidence, we suspect hardly anyone will disagree with the conclusion that feudalism as an economic force is dead, and as a political force is well on its way out.

More important than describing just something that has happened in the past, it will help explain why the Pakistan Army has faced an increasingly uphill task in creating a political arrangement that works to its liking, and why outright military coups are no longer possible not just because of perceived American pressure.

This magazine likes to consider itself strictly focused on business and the economy, and we have historically shied away from talking about politics for the simple reason that there are plenty of people with astute analysis about Pakistani politics, but far fewer who can talk about Pakistani business and its economy. We would rather stick to what we know.

But at times, talking about politics becomes unavoidable. We are not naïve enough to think that politics is downstream of economics, or vice versa. The relationship between the two is far more complex. And while we will never become a publication with regular content about politics, when the economic half of political economy deserves to be highlighted, we will offer our analysis for consideration.

In this story, we will talk about the origins of Pakistani feudalism and its most recent iteration, how its economic and political strength manifested itself, and what were the secular economic trends that have sapped it of its power. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan

very insightful and clarity giving. thx

i love your analysis. it gives me hope even within all the mess we find ourselves in