One of the most annoying moments in the field of business journalism is when different industries whinge to journalists about everything that is wrong and how the government needs to help them. The whiny, entitled, nature of these industrialists demanding that the government bail out their sector whether it is leather, or fabrics, or metal, or chemicals is so predictable yet so nauseasting that it is stranger when a subsidy, or a package, or some form or relief does not come up in an interview.

This is not, of course, to say that subsidies are always bad. While most businesses need to stop complaining and start taking more responsibility, there are classes of people who desperately need and deserve subsidies from the government. We are speaking here specifically of farmers. Most of the times, when subsidies are looked at critically, the opposition to them is that tax payer money is being used to provide relief to some sectors or organizations. This money could be used elsewhere such as poverty elimination programs, development expenditure, or any place else by the government.

One subsidy that always is in the news cycles is fertilizers – more specifically urea.

The subsidy on urea is provided in different ways. The government, for example, provides subsidised gas to fertilizer companies so that they can produce cheap urea and provide it to farmers. Now, this subsidy is being provided to fertilizer manufacturers, but eventually it affects farmers that end up buying cheaper urea from these fertilizer manufacturers. However, there are different ways in which this subsidy can be provided that more directly benefits the farmers rather than the fertilizer companies – which should be the government’s target.

There are gains associated with the subsidies in the fertilizer sector, making subsidies in the sector a public policy tool. In the past, governments have subsidized production, import, and distribution; and have also withdrawn the support only to revert back when prices rose. In short, one could say that this policy tool also works as a political tool to garner support from the farming population (which also happens to employ a significant proportion of Pakistanis), but also helps ensure food security.

The size of the agricultural sector

Pakistan is an agrarian economy. This little factoid is drilled into our heads from our earliest school days. It is plastered front and center in social studies books, and is most likely the first thing you learn about Pakistan’s economy and topography. This agrarian bent, along with an inexplicable pride in being rich in natural resources (as if that sets Pakistan apart from the rest of the world), goes to the core of how we try to portray ourselves as a country.

That is exactly what fertilizer companies try to play on as well. Just think of television and radio adverts for fertilizers. One farmer tells another of how his crops have done magically well thanks to this new fertilizer. The other is shocked but intrigued, prompting the former to explain the details of how the magic of urea has changed his life and fortunes, and the latter scurries off to buy said fertilizer. For good measure, we sometimes even get a shot of farmers dancing off into golden hour as they spread the fertilizer in their fields to the beat of flute music.

The reality is a little different. The people benefiting most from these subsidies are not small time farmers, they are major landowners that control most of the country’s agricultural land. Agriculture is a sector in which Pakistan’s wealth gap is most palpable. According to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), a mere 10% of zamindars hold 52% of the agricultural land in Pakistan. Currently, we employ an across-the-board subsidy on Urea imports that is costing tens of billions of rupees, and hurting both the country’s balance of payments and fiscal deficit. It also means that the richest farmers with the largest land holdings reap most of the rewards from these billions that the government is pouring in.

Meanwhile, the actual hard working farmers that these ads fail to mention make up a large portion of Pakistan’s workforce. However, access to fertilizers can often be a life changing factor in the lives of farmers, especially those working on a small scale. As such, there is no surprise that fertilizer is one of the most subsidised products in the country, and for good reason. A staggering 39% of our labour workforce is employed in the agriculture sector, 66% of the population depends on the agriculture sector for its livelihood, it makes up 19% of our GDP, and makes up 20% of our exports, not including the input it provides for the textile industry, which makes up for 60% of the country’s exports.

The history of fertilizers in Pakistan

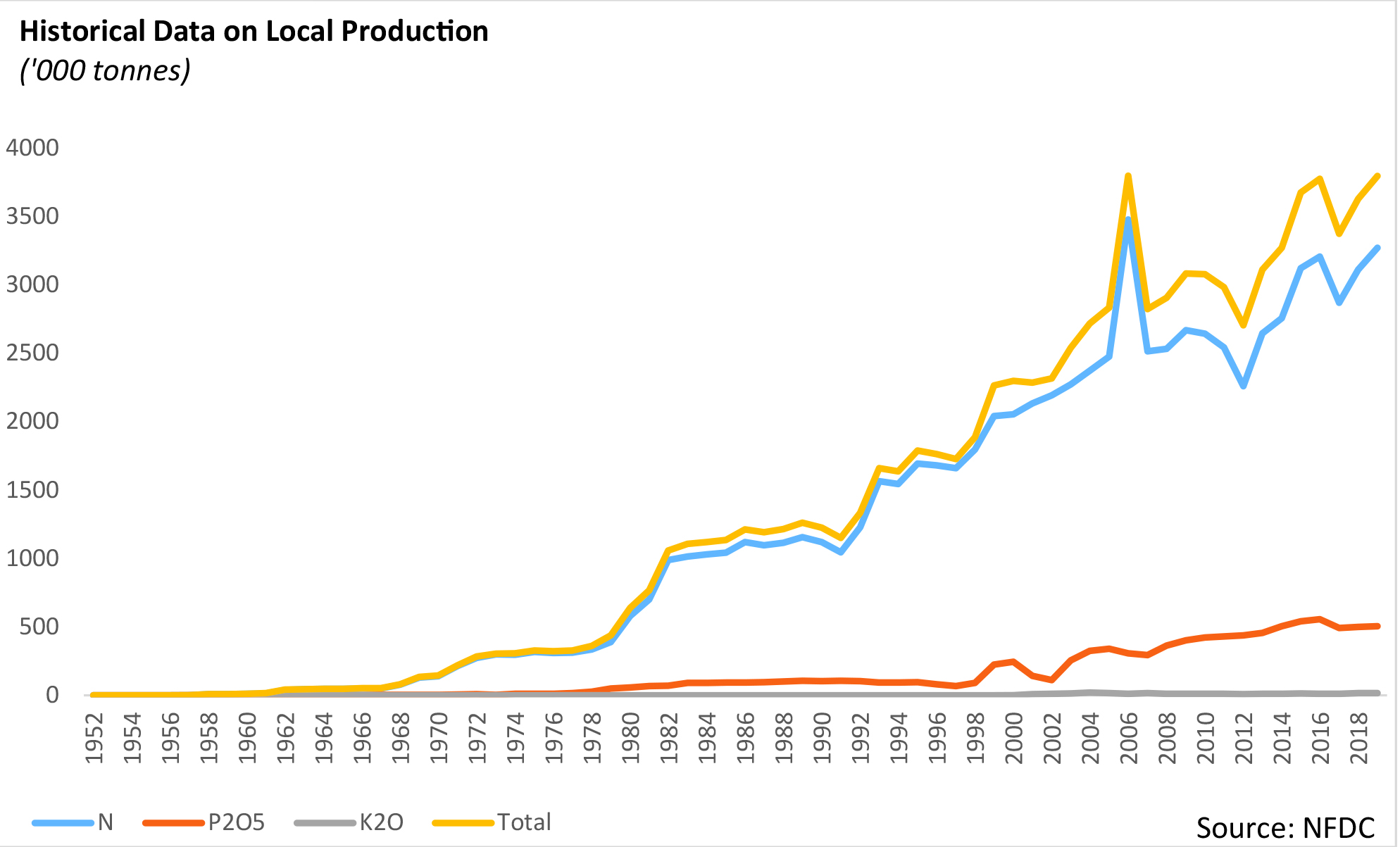

Manufactured fertilizers were first introduced to farmers in the 1950s and were imported from abroad. Nitrogenous chemical fertilizers came in 1952, phosphorus in 1959, and potassium in 1967. The use of fertilizers particularly picked up steam during the Ayub era five year plans, and as farmers got used to the higher yields that these fertilizers brought, and with Pakistan having natural gas reserves, Pakistan began to produce its own fertilizers.

This was an import substitution policy that was carried out through strategic manufacturing investments to push the fertilizer industry in Pakistan. Investment came in the form of joint ventures such as the Pak-American Fertilizers (now Agritech) in 1958 and Pakarab Fertilizers in 1973. Domestic investment came in from Fauji Fertilizer Company much later in 1978.However, in 1973, Pakistan went through a nationalization wave, and all fertilizer companies were now undertaken by the National Fertilizer Company.

The industry was able to grow because of the abundant gas supply that enabled the companies to increase their output. This helped Pakistan save out on foreign currency that would be used to import fertilizer. Another boost to this industry was when farmers started using more fertilizer in 1970 as they adopted high-yielding modern wheat and rice varieties that were also supported through subsidies and research support by the government. The growth of the domestic fertilizer sector has been consistently higher than the growth of consumption for all nutrients since 1971. As a result of this, imports have laid low.

Industry dynamics

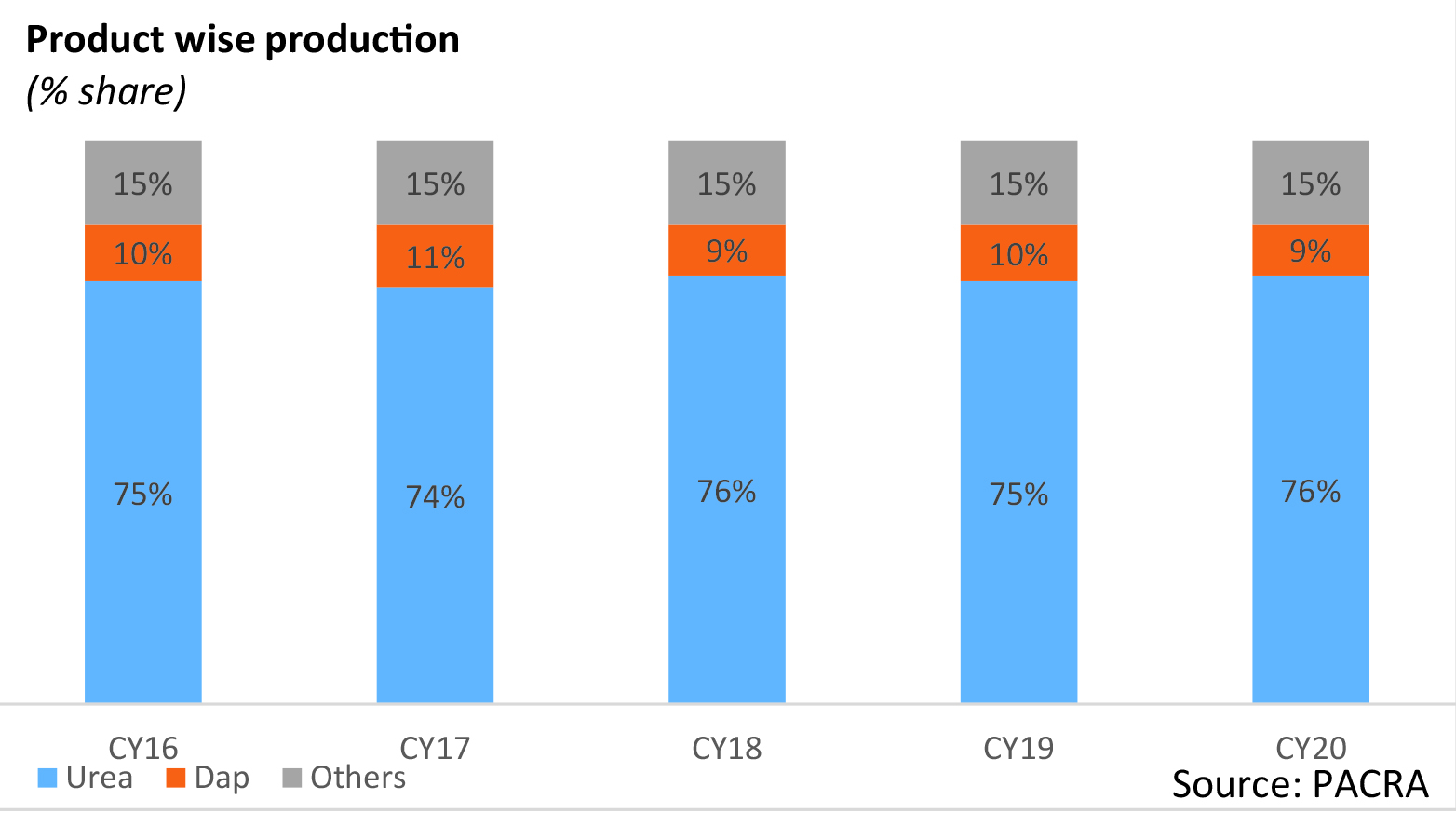

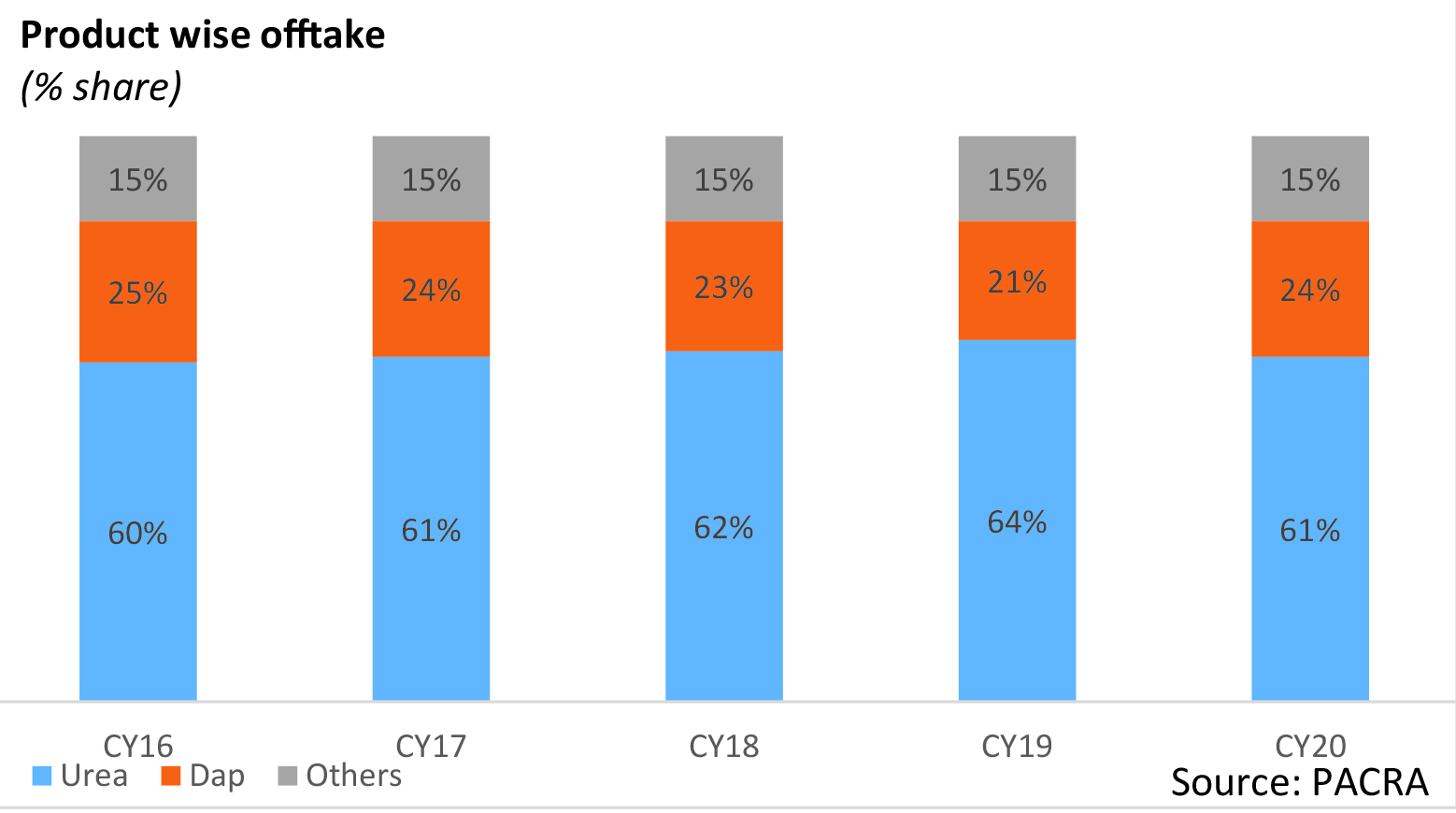

The industry is now dominated by 5 companies that make up 95% market share. Four of these are listed on the PSX. The sector contributes 4.4% to the LSM sector and 0.9% to the overall GDP. The sector posted revenue of Rs 381 billion in CY2020. 62% of the sales were made in Urea, whereas 22% in DAP. The annual fertilizer uptake in CY20 is 9.7 million tons.

Urea makes up 75% of the country’s fertilizer production and DAP accounts for 8-10% of the country’s fertilizer production. FFBL is the only DAP producer, the rest are involved in the import. Urea makes up 61% of fertilizer offtake and DAP makes up 24%. The demand for urea stays range bound between 6-6.1 million tons annually and isn’t as price sensitive as DAP.

Local urea prices are cheaper than international urea prices. The difference between the prices was as high as 41% in CY 18 and 46% in CY19 as a result of a tightened global supply and increase in in-house capacity.

The price of urea in Pakistan depends on gas price fluctuations, GIDC impact, and sales tax allowance. While there has been a rise in prices across all other sectors, urea prices have increased by 1.6% over the past 8 years which shows a slow growth rate. The price of a bag of urea was Rs 1690 in 2012 and Rs 1718 in 2021.

As per an analysis by Engro Fertilizers, farmers spend 34% towards inputs. 6.7% of the money spent on inputs is for purchasing fertilizers. Urea makes up 2.8% of the money spent by farmers, making it a small component.

The Fertilizer Policy

The fertilizer policy of 2001 primarily focuses on the provision of a gas subsidy to fertilizer manufacturers. “It is the intent of this policy to provide investors in new fertilizer plants in Pakistan a gas price that enables them to compete in the domestic market with fertilizer exporters of the Middle East so that indigenous production is able to support the agricultural sector’s requirement by fulfilling fertilizer demand,” says the policy.

The policy is a clear example of import substation whereby the country meets its demand for a product through indigenous sources. Due to the policy, plants were provided differential and low rates. This was to encourage more investment in the industry. Engro and Fatima Fertilizer are beneficiaries. A downside of the policy is that it does not focus on the distribution, demand and utilization of fertilizers.

The policy resulted in a dual price system where one price exists for fuel stock for general use and one for the fertilizer industry that gets a price closer to the Middle East price. This subsidy is for all urea producers.

In addition to this subsidy, there is a subsidy for the import and distribution of fertilizers to ensure reasonable price levels domestically. What it does is that it buys higher priced fertilizer and sells it at local rates.

Does this subsidy make sense?

Before the 1980s, Pakistan used to import more than 50% of its fertilizer to meet domestic demand. Despite an expansion in the industry, imports grew between 1989 and 2001 due to an increase in demand. In order to incentivize investment, subsidies were given out to encourage new players. This is why the Fertilizer Policy 2001 came into being.

The policy resulted in more than Rs 162 billion investment from local players and translated into an increase of 1.9 million tons per annum capacity. The subsidy meant that Pakistan no longer remained a net importer of urea. Instead there is now an export opportunity whereby up to 1 million tons of urea can be sold internationally. Potentially earning 400 million. This is using current capacity and infrastructure.

Keeping in mind the fact that urea prices still lay close to 2012 levels shows that urea prices have declined in real terms. This also means that the food inflation we’re witnessing right now would be worse if there had been no subsidy.

When it comes to subsidies, there is never really a right answer on whether it is worth it or not. Why? Because while you can quantify the impact, the decision to go forward with a subsidy or withdraw it remains a value judgment that depends on factors beyond computation.

However, if this subsidy is withdrawn one can expect the price of urea to be somewhat similar to the international prices, which is approximately Rs 3000/bag higher. This means that fertilizer companies may reduce their supply keeping in mind the rising cost of production, and the market will meet its demand through imports. The demand for fertilizer will also shrink considerably and will result in a reduction in crop yields.

Urea Fertilizer plants are more efficient with their gas utilization in comparison to other usages such as household utilization and gas turbines. With the incumbent government focusing on agriculture through the launch of Rabi Package, Kharif Package, and the Kamyab Kisan Package, it is evident that this subsidy is going nowhere, especially in light of the current levels of inflation.