Onions make you cry. Whether you’re making an omelette, or preparing a salan, the moment you cut into the onion, its cells release a compound that is a form of sulfuric acid. The fumes rise up and irritate the nerves around the human eye, causing it to water up.

Of course, onions can make you cry for other reasons as well. In Balochistan’s Chagai district, Salim Ahmad tells us the story of the first time he cried during this year’s flood. It was early August, and the rains had been pouring down for over a week at that point.

Chagai was one of the first places to be hit by the floods in Balochistan. On the first day of the monsoon, Ahmad remembers thinking these were some of the heaviest rains he had seen in his lifetime. By day three, he knew it would be disastrous for the onions and melons he was growing on nearly 12 acres of the land he manages.

The onion, as Ahmad explains it, is a rough vegetable by the time it is harvested but incredibly delicate during its growing period. The stem holding the bulb is fragile, and a single tread too heavy can dislodge the onion and wilt it within hours.

Still, Ahmad held his nerve. When the rains went on for a week, the hill torrents in the north came crashing down and the water started piling up on his farm, he knew the crop was gone. His wife was concerned, pacing up and down. Still Ahmad did not shed a tear.

It was near the 10th day, when the rain abated for a moment that Ahmad and a few of the people working on the farm went out to see whether anything could be salvaged. “One of the farm workers had his young son with him. The boy had never seen anything of the sort, when we were inspecting one cluster of the onions, he wandered off without anyone noticing. When he came back, he had with him exactly three dented onions that he found floating or submerged in the water.”

The child handed the onions over to his father. “These are the only ones I could find, the others are all gone,” he said. That, as Ahmad tells it, is when he finally wept. Both for the crop that was lost and for the aeons it would take for both the farm and its people to recover from the destruction. “The Baloch country is arid. Rain-fed areas are regularly short of water since most water channels belong to the sardars. But the onion is a special crop to us. Not only does it grow on our land, it thrives here more than anywhere else.”

Soon, it may not be just Ahmad who is crying. The onion supply-chain is susceptible to delays and difficulties in good years, particularly in the winter months when the onion has to be imported. In the months to come, the extent of the damage of the floods will become clear. The two main onion producing provinces, Sindh and Balochistan, are entirely devastated. Which means the prices of onions will spike and cause strife both in urban and rural areas.

A majority of this year’s onion crop has already been decimated. Since nearly the entire crop in Sindh and Balochistan is gone, estimates put the level of destruction to as much as 77% of all onions grown in the country — some 10 tonnes. Prices have already shot up in urban markets by more than 40%, and will continue to do so, even as the government is banking its hopes on importing onions and tomatoes from across the western borders with Iran and Afghanistan. While import duty has been removed on these two products, it will still mean a major staple good will see significant inflation.

The Pakistani onion

The onion is a much bigger deal than one might think. Calorically, it is not the most nutritious or efficient food. Onions are nearly 90% water, and raw onions contain only 40 calories per 100 grams. By fresh weight, it contains 89% water, 9% carbs and negligible amounts of fibre, protein, and fat. But along with tomatoes, onions hold a unique place in Pakistan’s culinary (and hence its agricultural) space. As one of the main components of salan, onions are in-demand throughout the year. For most months, locally grown onions are enough to meet the demand. Onions are grown on around 136,000 hectares of land, with the 2020 figures showing a total yield of 1.74 million tonnes across all provinces and regions of Pakistan.

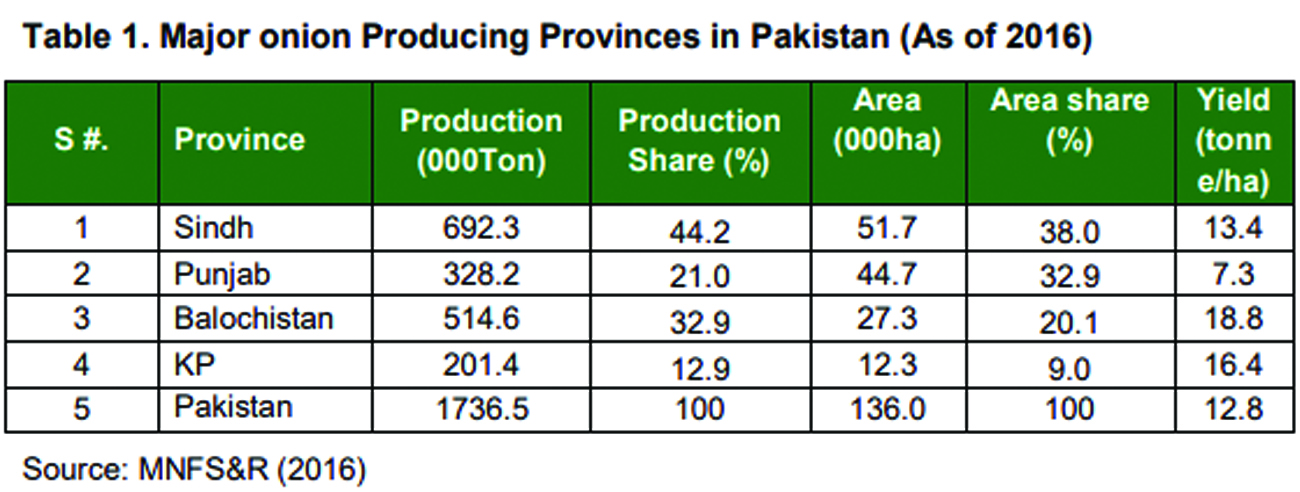

The citadel of this humble condiment is Sindh, which contributes about 38% in area and 44% in onion production of the country followed by Balochistan which contributes about 21% in area and 33% in production. Punjab actually has more land dedicated to growing onions than Balochistan, but because the province has lower yield and produces a drier, less-red variety of onion its yield is less. Overall, the average yield in Pakistan stands at an estimated 12.8 tonnes per hectare.

The province-wise breakdown of onion yield presents a fascinating picture. The latest available data is from 2016-17, but according to officials from the Ministry for National Food Security the patterns of onion production have not changed significantly in the past five years. Balochistan has the highest yield per hectare with 18.8 tonnes per hectare, while Punjab has the lowest yield at a measly 7.3 tonnes per hectare. KP also has a high yield at 16.4 tonnes per hectare, but has the lowest area that is under cultivation at only 12,300 hectares.

For all intents and purposes, onions are grown in Pakistan in what can only be described as three clusters. Much like there is a ‘kapas’ belt running from South Punjab to Sindh and a mango belt running alongside the Indus through the same region, onions have their select regions. The cluster in Sindh consists of Mirpurkhas, Umerkot, Jamshoro, Matiari, Sanghar and S. Benazirabad with Mirpurkhas as its centre point. In Balochistan, Changai on the tip of the Balochistan tail is the onion headquarters, with the cluster stretching eastwards along Mastung, Kalat, Turbat, Nasirabad, Kuzdar, Kharan, Quetta and K.S. Ullah.

The woes of the onion

These nearly 13 tonnes of onions that Pakistan produces are usually enough for most part of the year. However, because onions are such a staple requirement throughout the year and an important caloric input in the average Pakistani diet, they are needed throughout the year. That is where the clusters come in.

The cluster districts in Sindh are the tail area of all the canals and mostly soil of the district is sandy loam to clay. In the cluster, sugarcane, banana and many other vegetable crops are grown with onion crops. The main focus of Sindh cluster is international markets through ships or cargo services. The nearest domestic markets for KP clusters stretch from Islamabad to Lahore. The Balochistan cluster covers the urban centres of Sindh and South Punjab. The cluster has a lot of potential. For the export window, the Sindh cluster can reach European and Middle Eastern countries. The Swat cluster can position itself for the China market, while the Balochistan cluster can target the Middle East markets.

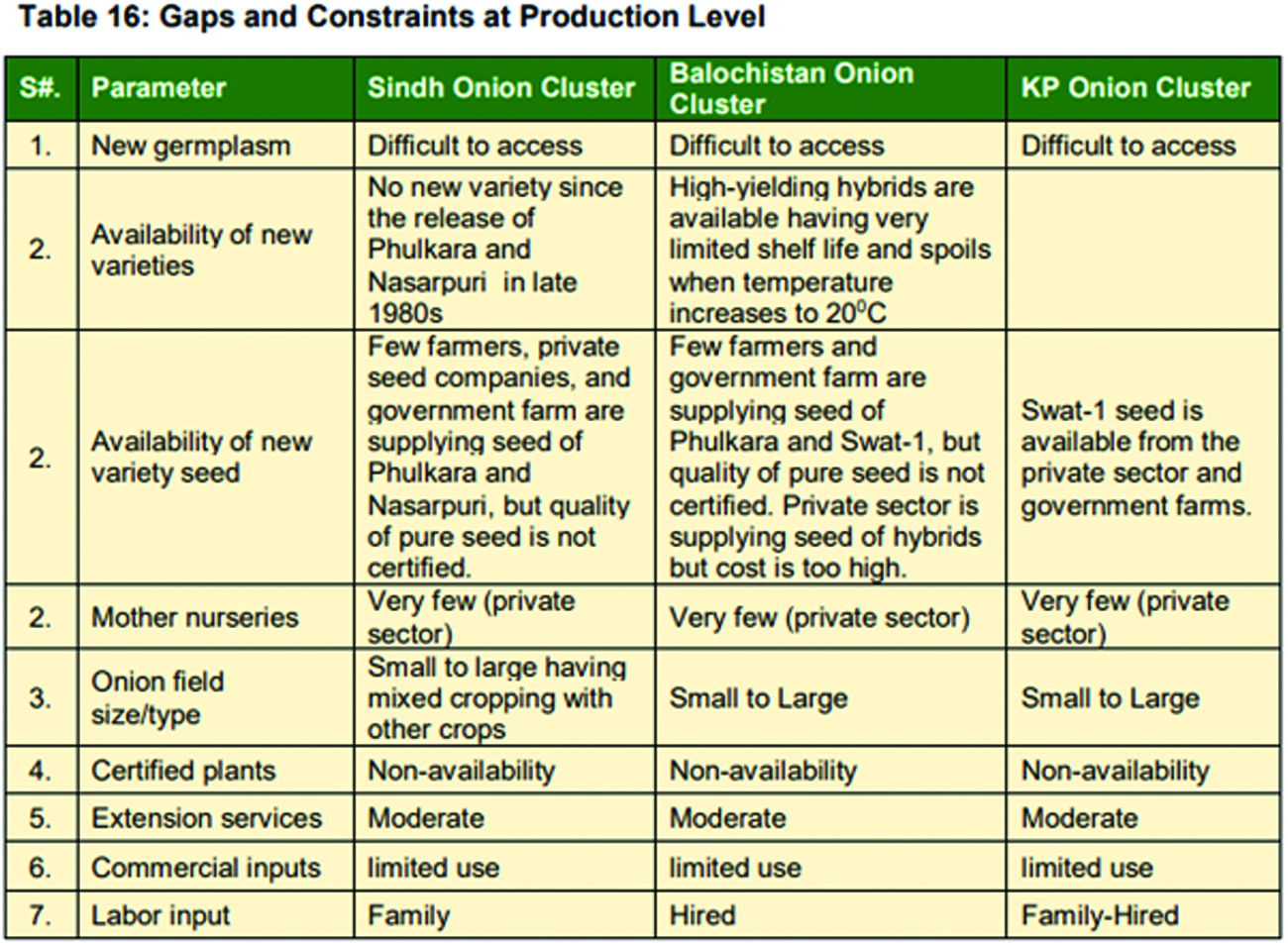

Unfortunately, however, the supply of onions has been dogged for a while. The last time modern varieties were introduced successfully in the country was in 1992. In our three clusters, Pakistani onion growers almost exclusively focus on red onions. In these, there are four varieties. There are the Nasarpuri and Phulkari which are grown in Sindh largely, and were a modern variety introduced in the 1980s. Then there is the Swat-1 variety which was introduced in 1992 to bolster production in the Swat and Balochistan regions. A lot has changed since then, especially with regards to the climate but more resistant varieties have not found their way to the market.

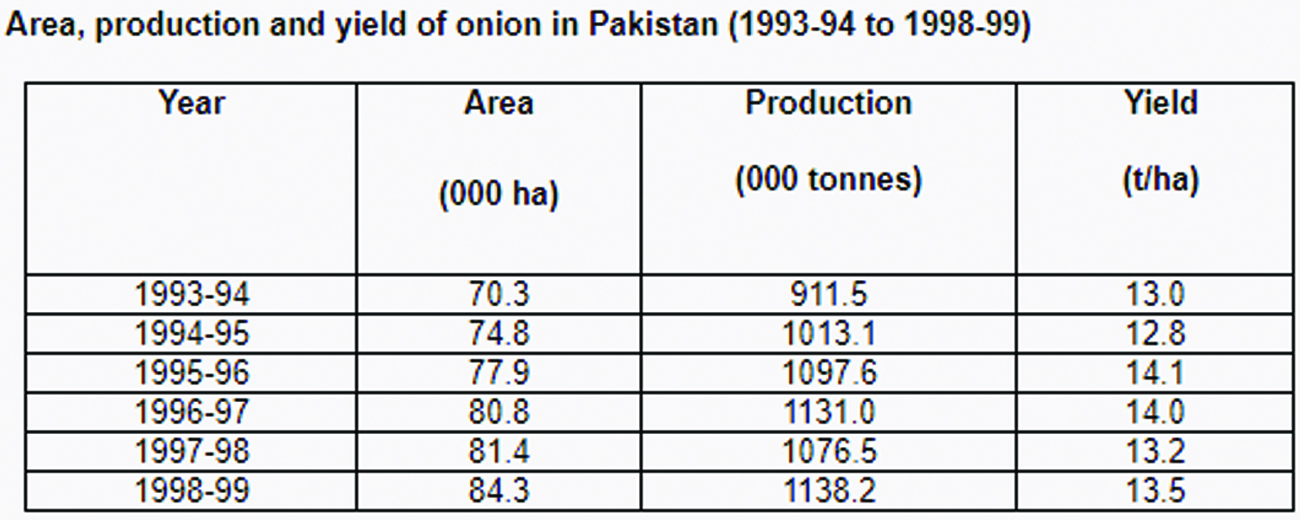

Back in the 1990s, the effect of the new variety was clear. In the period following the introduction of the Swat-1 variety, from 1993 to 1999, there was a significant increase in both the area under yield for onion production and the overall yield per hectare.

Onion varieties cultivated by farmers originate from a smaller pool of genetic material, which degenerate and degrade over time, and there is very little infrastructure to replenish them. According to a report of the Planning Commission from 2020, “The Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC) has regularly failed to supply sufficient germplasm and develop new onion varieties. The available resources are spent on buildings, personnel and overheads, and there is no money left for research and development. This means highly qualified scientists are just sitting at their desks.”

This is not where the failings end. Seeds used and distributed are subpar, farmers are given the wrong kind of fertilisers by self-serving commission agents, and all in all the crop suffers where the area and yield both could be much higher. Onions are harvested manually in all clusters, despite the urgent need to mechanise.

The onion supply chain

Since the sowing and harvesting times vary for all of these clusters, there is often a shortage in different areas of the country and prices fluctuate geographically. But the market gets particularly hot during the winter months, with inflation increasing by as much as five times in some dry months. So for example, if the crop is in the sowing period in KP, it will be more expensive in Islamabad and north Punjab, and onions will either have to be imported or brought in from Sindh. But since Sindh produces very fine, export quality, red onions are expensive within the country as well. The onion crop is technically a Rabi one, which means it is sown in the winter around mid-November and harvested in late April – early May.

“There are three distinct ways of growing onions. The first is sowing seed directly in the field where the crop is to mature. The second is to sow in a seedbed from which the plants are transplanted later to the field, and the last popular method is planting pre-grown sets. A grower may buy these sets, or grow them from the seed himself. The transplanting method is used more commonly for early production,” explains Khalid Mahmud Khokhar of the Pakistan Agriculture Council.

“The nursery for the autumn crop of onions is raised in the first week of July and the seedlings are transplanted in the field in the middle of August for harvesting of bulbs during December. It is difficult to manage nursery seedlings of autumn crops because of high temperature and monsoon rains. Sometimes, the heavy rains cause severe damage to nursery seedlings.”

Essentially, what this means is that while onions are grown at different times, one of the major periods in which a large part of the overall yield is harvested is around July-August. Even in normal years, the supply of onions falls short during December-January and prices soar to more than five times compared with normal season. Normally, the government mitigates this through the import of onions and tomatoes from across the border in Afghanistan and Iran. It would, of course, be a much simpler process if trade were active with india.

This year, because of the floods, the onion crop along with other crops in Sindh and Balochistan was wiped away almost completely. To get a measure of this, that means around 77% of the all onions grown in Pakistan. And since this was close to one of the harvest periods, the supply chain has already been affected immediately. The price of onions in the federal capital shot up to Rs 300/KG within days while in Lahore it went up to Rs 400/KG.

The government has gone back to relying on imports to try and cut the prices. They have also exempted sales tax and withholding tax on the import of tomatoes and onions for a period of four months, especially from Afghanistan and Iran, to arrest the skyrocketing prices of the vegetables in the domestic market in the aftermath of heavy rains and floods. Perhaps, the biggest window into just how serious the shortage could be is that the government may have to consider the possibility of importing from India.

What can we do for our onions?

Let us be straight, if harsh, for a second. These floods are a natural disaster that have been caused by climate change. The problem is, this will not be the end of it. Next year, a different climate-related disaster could stare us down and bring our agriculture to its knees. That is not to say the scale will be this big every year, but the change will be visible.

Temperatures will rise. As we keep being told, this is the coolest summer of the rest of our lives. Water will go from being short to being too much. As a result, crops will suffer. Many people do not understand this but the science of agriculture and the art of farming are separated. The science of agriculture is a technical one, full of genetic engineering and hard data. The art of farming has to do with the soul. Only a farmer that has spent his entire life planting a certain crop knows not just technicalities like what its sowing time is and how much water it needs, but really what the personality of that crop is.

Go back to Ahmad from Chagai with whom we started this story. Think about how he described the onion — as a rough, hard vegetable once it is harvested but a delicate, fragile sapling that is swaddled by the very soft earth that it thrives in. It is a vegetable that has ‘nakhray’ as the farmer tells us. Yet at the same time it is resilient, having a thicker skin (both literally and figuratively) against things like pests and disease.

To fix where we stand, we must use the science of agriculture to complement the art of farming. Our farmers know their land best, but they are facing an era in which the land is fast changing and so is the environment. Science must help them adapt to it. We must use better seeds. We must use more adaptable varieties of these plants and make sure that they get the right amount of water at the right time through not just proper scheduling, but techniques such as drip irrigation.

The threat posed by climate change to the onion is massive. The Sindh, Balochistan, and KP clusters are all very different, but they have similar issues which makes it easier to make a cohesive policy. Water shortage, humidity, monsoon rains and dust storms causing lower yield in Sindh cluster. Late frost in and strong dusty/sandy winds and storms in Balochistan during flowering/ blooming season greatly impact the yield and quality of production. Climate change related impacts, such as new diseases and shifts in crop cycle are also emerging issues in the regions. In Swat, the cool temperature and snowfall affects the yield of onions.

In recent years, the overall area that has been under yield for onions has fallen. People in the onion business claim that it is no longer a reliable source of income because of the shortage of water. Due to shortage of the crop, the price of the produce in the local market was higher than the last couple of years. While the onion could actually be a major export oriented crop for Pakistan, it is instead languishing with its export potential not even close to reached.

There is a clear path ahead of us here, and there are not really any two ways about it. On the one hand, we can choose to fund agricultural research, improve the linkage between farmers and research bodies, and see Pakistan becoming not just stable on the food security front, but also hopefully in a position to be able to export as well. The other path is continued apathy, on which we have been for decades. The results will not be pretty. And yes, it will be more than the onions making us weep then.

*All data, facts, figures, and tables have been taken from the Planning Commission of Pakistan and the Ministry of National Food Security & Research.

Good Point

detailed and excellent

I have perused every one of your posts and all are exceptionally enlightening. Gratitude for sharing and keep it up like this.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com

I’m a professional in all kinds of hacking services, which leads me into giving out a blank ATM card to all individuals & serious minded people only, We have help so many people and make them rich, this is real and guarantee sure our Atm will be attached to any serious buyer.

HERE IS OUR PRICE LISTS FOR THE CARDS

1,000 USD daily for 2 weeks cost 300 USD

1,000 USD daily for 1 month cost 500 USD

1,000 USD daily for 2 months cost 800 USD

1,000 USD daily for 3 months cost 1,000 USD

1,000 USD daily for 6 months cost 1,600 USD

1,000 USD daily for 1 year cost 2,700 USD

1,000 USD daily for 2 Years cost 4,800 USD

1,000 USD daily for 3 Years cost 8,900 USD

Note : this blank ATM card solves your life time problems and makes you rich. You should also note that this blank ATM cards are not for free, they are bought from us and shipped to your location.

We deal with serious people who want this Card.

Email : darkwebonlinehackers @ gmail . com

WhatsApp: +1 (803) 392-1735