It would be an understatement to say the Cholistan Canal Project has triggered outrage. The project, which aims to dig six new canals intended to irrigate barren lands in South Punjab, particularly Cholistan, has been met with widespread public outcry. The loudest voices against the project have come from Sindh, where protests have erupted across the province.

Demonstrators accuse the government of neglecting their water rights. In Karachi, Hyderabad, and multiple rural districts, farmers and activists have taken to the streets, warning that their already fragile agricultural system cannot withstand additional water shortages.

At its core, however, the Cholistan Canal controversy is not simply about Punjab versus Sindh. It is a symptom of Pakistan’s chronic failure to expand its water infrastructure to meet growing demand. Instead of engaging in political battles over existing allocations, Pakistan must recognize the real problem: there simply isn’t enough water to share when needed. Decades of inaction have led to a situation where provinces are forced to fight over a stagnant water supply rather than focusing on increasing availability through better storage, conservation, and management.

The 1991 Indus Water Apportionment Accord: A Forgotten Vision

The 1991 Indus Water Apportionment Accord was a landmark agreement designed to ensure the fair distribution of Pakistan’s most precious resource. However, over time, discussions around the Accord have become narrowly focused on Clause 2, which deals with water apportionment, while neglecting the broader, forward-looking provisions aimed at securing Pakistan’s water future.

This agreement was never meant to be just a water distribution formula. It laid out a comprehensive vision for water management, addressing storage development, surplus distribution, ecological sustainability, provincial autonomy, and efficiency in water use. Unfortunately, delays in implementing key provisions, especially the construction of new reservoirs, have turned water allocation into a source of conflict rather than cooperation.

To truly understand the significance of the Accord, we must go beyond Clause 2 and explore its holistic framework, clause by clause.

Clause 2: Not the Whole Accord

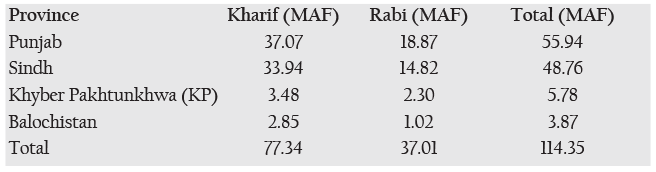

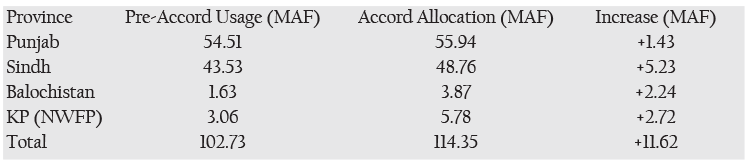

Clause 2 of the Accord established provincial water allocations from a total of 114.35 Million Acre-Feet (MAF). These allocations were based on provincial demands and needs. However, at the time of the Accord, 102.73 MAF was already in use, creating a gap between existing usage and the newly allocated shares. The agreed allocations were as follows:

Despite being a cornerstone of the Accord, Clause 2 was never meant to define the entire agreement. It was always intended to function alongside other key provisions, particularly those related to storage development (Clause 6), surplus distribution (Clause 4), ecological protection (Clause 7), and efficiency improvements (Clause 14). Unfortunately, the failure to implement these provisions has led to recurring disputes over water shortages, overshadowing the broader vision of the Accord.

Clause 4: Managing Surplus and Future Storage

Clause 4 provided a mechanism for fairly distributing surplus water, particularly during the Kharif season, among the provinces:

- Punjab: 37%

- Sindh: 37%

- Balochistan: 12%

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: 14%

However, without adequate storage, this clause remains ineffective. The Accord envisioned that additional reservoirs would allow provinces to better manage seasonal surpluses and prevent wastage. Yet, because planned reservoirs were never built, surplus water often flows unused into the sea, while shortages continue to spark inter-provincial disputes.

Clause 6: The Need for Storage Development

One of the most crucial but overlooked provisions of the Accord is Clause 6, which explicitly recognized the need for new reservoirs:

“The need for storages, wherever feasible on the Indus and other rivers, was admitted and recognized by the participants for planned future agricultural development.”

Had this clause been fully implemented, Pakistan would have been far better equipped to manage water distribution. Sindh, in particular, stood to gain the most from additional storage:

Despite this intended increase, Sindh and other provinces remain water-stressed due to the failure in building new storage facilities.

Clause 7: Ecological Protection

The Accord also recognized the importance of minimum downstream water flows to prevent sea intrusion and protect Sindh’s delta. Sindh initially proposed a 10 MAF minimum flow, but further studies suggested:

A minimum annual release of 3.6 MAF, split evenly between Kharif and Rabi seasons, along with an additional 25 MAF over five years to be released during Kharif. The continued degradation of the delta region shows that this provision has not been effectively implemented, leaving coastal communities vulnerable.

The Way Forward: Fulfilling the Accord’s Promise

The 1991 Water Accord was designed to promote cooperation and ensure long-term water security. However, its incomplete implementation has led to disputes rather than solutions. In order to realize the full potential of the Accord, Pakistan must take urgent steps to address its shortcomings. The construction of new reservoirs must be prioritized to meet the country’s growing water demands. Additionally, fair surplus distribution mechanisms should be reinforced by improving flood management and infrastructure.

Ensuring ecological protections is also crucial to prevent further environmental degradation, particularly in Sindh’s delta region. Furthermore, provinces should be empowered to develop their own water resources as originally envisioned in the Accord. Finally, agricultural needs must be prioritized over hydropower generation to support national food security.

The 1991 Accord is not outdated—it is an untapped solution for Pakistan’s water challenges. By shifting the focus from conflict to implementation, Pakistan can secure its water future for generations to come.