“He buried his father inside his uncle’s grave,” I hear a man say as I sit inside a ramshackle government office chatting with Bashir Ahmad, the security officer at the Miani Sahib Graveyard in Lahore. To some this might seem a bit of a stretch from reality, but taking into account the already limited spaces for graveyards in Punjab – year after year get closer to their full capacity – the situation makes a little more sense.

In all its totality, the issue as social in nature as it seems, is more importantly an economic one. In the United States, graveyards are managed and run like any commercial enterprise, keeping their financial sustainability in mind. The owners of the cemeteries do this by taking a proportion of the money generated from the sale of new plots, and investing it into what is essentially a perpetual ‘retirement’ fund. The time till the facility reaches its full capacity is considered its ‘working life’ where it saves money for its retirement, which once invested provides a constant stream of income and is used for its maintenance and future expansion.

With no such model in place in Pakistan, graveyards, in general lack in maintenance and become a burden on the government or the bodies managing them. “The cost of a plot at Miani Sahib is only Rs500 and an additional Rs8,000 is charged for the preparation of the grave that is spent on building material and paying for labour,” says Bashir Ahmad. Another major income source are the shops around the graveyard – mostly selling flowers – that are auctioned to the highest bidder and pay a decent rent, he further informs, without disclosing the actual rate.

Primarily, a social service

However, Asif Mehmood, the former deputy secretary at the Punjab Board of Revenue claims that the rates at which these shops are auctioned are low and raising them to their actual market rate would be a step closer to making the graveyards more financially sustainable. “Due to the social construct we live in, people generally consider the burial process a social service to its core. We need to change this perception to make graveyards more sustainable and improve the quality of these facilities,” he insists.

But it seems, that the provincial government (at least for now) plans to treat graveyards primarily as a social service. Its recent project, ‘Shehr-e-Khamoshan’ initiated under the Chief Ministers Strategic Reforms Unit, that aims to build model graveyards in 36 cities across Punjab, three out of which are already operational in Lahore, Faisalabad and Sargodha, is a step in that direction.

The scheme envisages provincial government providing hearse, janazgah, ghusal and mortuary services all available under one roof.

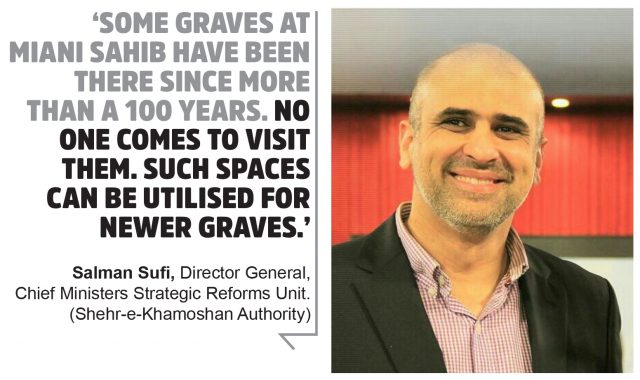

Under the initiative, the graveyard in Lahore alone has been built on a land measuring more than 11 acres, 89 kanals to be precise, at a cost of Rs155 million, with space for approximately 8,000 graves. “We have not ruled out the possibility of a proper sustainable financial model for these graveyards, but for now the chief minister’s vision is that these facilities should be treated as a social service to provide maximum facility to the citizens,” insists Salman Sufi, the director general at the Chief Ministers Strategic Reforms Unit.

As of now these model graveyards are charging around Rs15,000 to Rs20,000 from those who can afford to pay. Along with the price of the plot and the aforementioned facilities, this sum also includes the maintenance of the grave. People who cannot afford to pay such a sizable sum – consisting of a large proportion of the people who come to bury their loved ones – are exempted from making any payment.

Philanthropists to the fore

Fatima Khan, a junior associate at the Chief Minister Strategic Reforms Unit, however says that even people who cannot afford, contribute as much as they can. “Some pay Rs1,500 and some pay Rs5,000, as they want to contribute towards the burial of their loved ones to whatever extent they can,” she claims.

But the money generated through these burials isn’t the main source of financing available to these graveyards. Working along the Punjab Shehr-e-Khamoshan Authority is a slew of philanthropists, and they make a generous contribution to its projects. For example, according to Fatima Khan, a large number of ambulances in operation under the project have been donated by a renowned corporate group.

The authority is working to attract more philanthropists to its cause. “We have a large number of people and organisations willing to partner with us,” she insists.

On the other hand, as urban spaces expand, available spaces for graveyards keep shrinking. In Europe and Saudi Arabia (for religious reasons), the issue is dealt with by flattening out the graves after a specified period of time to make space for new burials in their place. On similar lines, the provincial government is now working to bring in legislation to make grave-flattening legal here with the only issue being that it is yet to decide upon a time frame after which the graves would be flattened out, says Salman Sufi.

“Some graves at Miani Sahib have been there since more than a 100 years. No one comes to visit them. Such spaces can be utilised for newer graves,” he concludes.