Deep into the winding, messy streets of a Lahore township, on one end of a broken road stands a building five stories high. The hustle and bustle of Punjab’s capital is reflected in the shiny, blue-tinted glass that covers its front from top to bottom. It is a massive structure, ugly on its own because of its bulk, but in the middle of the decrepit area it stands in, it looks sleek almost, as if its silver arches and vast expanses of glass were picked up and air-dropped straight from some science fiction novel.

Housed in these five stories is a Lahori media empire. This is the headquarters of the City Media Group, where local journalism and business come together in a melting pot of innovation, risk, and novelty. Under the City Media Group umbrella fall five television channels and an Urdu tabloid-sized newspaper. Key to the group’s success has been its willingness to do what no one else had thought possible.

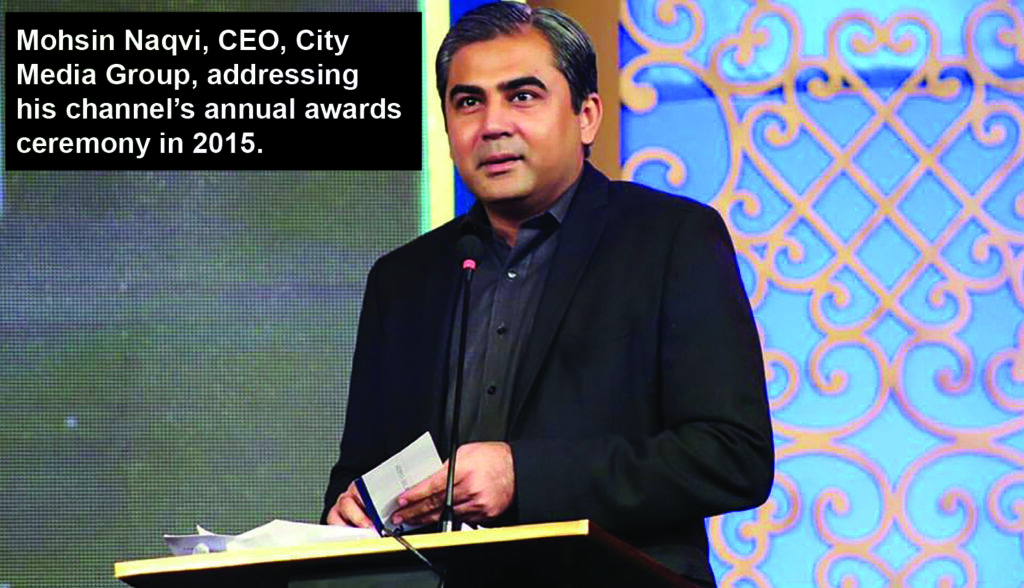

At the center of this innovative zeal has been one man: Mohsin Naqvi. Standing outside his simple glass-walled office in a corner of the media group’s headquarters, he does not look like the shrewd media tycoon he has grown into over the years. He listens patiently as an exasperated starlet explains some problem or the other in hosting a Ramzan transmission running on his channels. Hands folded behind his back, his neck is craned downwards almost in deference, as he nods along to everything, whispering gentle reassurances. But the amiable manners and speech is not a gimmick; he seems like a genuinely humble man.

He does not see guests often, preferring to work behind the scenes. When he does, he proves to be an attentive host and is easy to converse with. But he shys away from interviews, abhorring direct quotation and the limelight like the plague. His white hair and impish smile give him the appearance of a sweet old uncle that lives in your neighbourhood. Everything about Mohsin Naqvi makes you want to relax, and convince yourself to let down your guard.

But clearly there is much more to him than the friendly, happy-go-lucky persona that greets you upon meeting him for the first time. Despite the meticulously tamed puff of more-salt-less-pepper on his head, Mohsin Naqvi is barely 40 years old, and has already clocked a decade in the news channel business. Today, the man has undeniable reach in Lahore, what with City42 (C42), his breakout project, making him one of the most sought after men in the city. His relationship with the country’s political elite is also tight-knit. The fact that he is married into the Chauhdhrys of Gujrat has not stopped him from enjoying a long-lasting association with their political rivals such as Nawaz Sharif. His ties run so deep, that it is also known that if you want to get through to former President Asif Ali Zardari, Mohsin Naqvi is the man to meet.

Since the formation of the C42, a Lahore-focused local news channel, he has gone on to open City41 (C41) in Faisalabad, UK44 based in England, Rohi TV catering to the Seraiki belt, and Channel 24, the group’s national-level current affairs television channel currently in the doldrums along with the rest of the media industry. The City Media Group also publishes an Urdu-language local newspaper that accompanies C42.

City Media Group has, by no stretch of the imagination, been a pioneer in the news media business. But what Mohsin Naqvi has very successfully been able to do is to adapt existing concepts, such as local television channels and newspapers, and make them a reality in Pakistan.

But where did Mohsin Naqvi come from, and how has he been able to become a mover and shaker in Pakistan’s news media industry in the past decade? More importantly, can his bringing together of the journalistic and the entrepreneurial help him survive the current crunch in the news media industry.

He has been an innovator throughout his career, taking routes and making inroads in uncharted territories, but how is he dealing with the rapid decay of the industry?

His launch of C42 in 2009 was his magnum opus, but will Channel 24 be the swan song in his career thus far as a media mogul? Disliking interviews and keeping completely out of the news himself, Profit held informal meetings with Mohsin Naqvi and some of his closest associates, to try and get a measure of both his personal story, and the state of the news media industry in the country.

City 42 and the birth of an empire

It was 2009, and a little known channel by the name of City 42 had just started appearing on Lahore’s cable networks. The name was not exactly revolutionary, having simply used Lahore’s landline telephone dialing code (042), but the concept was: a channel dedicated exclusively to local news about Lahore, which quickly became one of the most powerful forces in the entire city.

As with any good local media outlets, the plan was simple, it operated like any regular television channel, with an hourly bulletin, morning shows and the works. If something really big happened in any corner of the country, they would go ahead and run it in the bulletins and news tickers, but what made them special was a host of reporters all concentrated in Lahore. Today, despite a national channel and three others as well as a newspaper, C42 remains the City group’s most important asset. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and Mohsin Naqvi’s idea got that two-fold, with the Dunya group and Neo news both coming out with local channels soon after C42 had really established itself. ‘Lahore news’ by Dunya, as they admit themselves, couldn’t come close to touching the heights C42 reached, despite having a much larger media machine backing it.

But becoming a trendsetter was not easy. After all, it was 2009 and the media industry was booming, especially the electronic media, though the good times had not come after their fair share of struggles. The industry had faced censorship and had been bloodied particularly towards the end of the Musharraf era. The year 2007 had taken a toll on journalists, what with the dictatorship at its ends and the lawyers movement.

But by 2009, the Pakistan Peoples Party-led administration of President Asif Ali Zardari had just come in. In a country starved of democracy, the ascendance of a liberal democratic party meant that the media was suddenly free, and the PPP-led government, in their excitement at having returned to office for the first time since 1996, seemed more than receptive, answering questions and providing information.

In this environment, television channels were popping up left, right and center. Not only was the business one that made you powerful, it was, back then at least, also profitable. So when Mohsin Naqvi went about making arrangements for a Lahore-focused channel, he was met with raised eyebrows. Why not just make a regular news channel? Sure, the costs would be more, but so would the pay-off. Besides, the risk of a local news channel failing was much greater.

But Mohsin Naqvi had a vision, and he was adamant it be brought to life. From the start he made sure that the entire set-up of his channel would have digital equipment, something the rest of the industry has only recently caught up to. Even the state-owned Pakistan Television (PTV) – the largest television network in the country by revenue and audience size – has not even done that, as was seen in the recent debacle of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s speech which was recorded on a digital camera and faced technical issues while running on PTV’s outdated broadcasting system. He was also clear on the style of channel he wanted, and the premise on which it would run.

Getting a channel like C42 to click with the audience was going to take a certain kind of reporting. And as one senior journalist who has worked with Mohsin Naqvi explains, he has above all else an excellent understanding of the media itself – if not journalism – but the industry.

To achieve the desired viewership, C42 employed the use of ‘reporter-man’ – the brash and the badtameez (ill-mannered) – the self professed superheroes out to expose small time crimes in those ridiculous ‘exposé’ news reports.

The scene is familiar enough. The reporter (if you want to call them that) armed with a microphone and a cameraman is on the prowl. He barges into milk shops, clinics, eateries and any number of places with all the bluster of a state organisation and goes about trying to ‘reveal’ all the evils surrounding that place. It is an art form perfected in Pakistan by the likes of Iqrarul Hassan Syed, ARY’s squint eyed, slick haired, perpetually enraged blue-eyed-boy, and practiced by countless television reporters trying to push and shove their way into the mainstream.

It takes a dash of brazenness, a little bit more rudeness, and a whole lot of loudness, but it is a doable bit. It is of course morally questionable, but more importantly from the perspective of C42, it is watched. With its fleet of reporters, C42 not just pulled this method of reporting off, they made it their style, and in doing so became an organisation not to be trifled with. As far as Lahore was concerned, everybody had to think twice before pulling something fishy, considering that at any moment a van from the channel could pull up and shove a microphone in your face.

But it wasn’t just these milk-shop exposes that gave C42 its dynamism. The channel was keeping an eye on literally everything going on in the city. If there is a wedding in Lahore with even a little socio-political clout, they would be there. If a street was in disrepair and left unattended, a reporter from C42 would quickly make a scathing rebuke of the provincial government’s governance. They would be the first to reach literary festivals, and their vans would be parked outside flower exhibitions well before time. And if a patient’s family is protesting the death of their family member outside a clinic? You bet C42 was going to be there too. Big or small, if anything happened in Lahore, C42 would be there to cover it.

But how in the world did Mohsin Naqvi manage to pull it off? Sure, he has a great understanding of the media, but where did that come from? He was not exactly a seasoned journalist before he made the dive into C42. And even if he just had a natural knack for it, television channels still require money. Where did the money for C42 come from? And how did he manage to turn a single local city channel into the media mammoth it is today.

The Mohsin Naqvi story

A Lahori by birth, Mohsin Naqvi was raised by his maternal uncle after he lost his parents at a young age. Today, his uncle also serves as the chairman of the City Media Group for Mohsin. He followed a pretty traditional path for boys from good families in Lahore. He was a sharp student at the City’s famous Crescent school, displaying early signs of leadership even back then. He followed that up by going to Government College, immersing himself in the Ravian experience. Even as a young student with an easy smile and a deferent handshake always at his disposal, his networking was legendary even then. Famously, even as a young undergrad at GCU he somehow established a relationship with the chief minister. He eventually found himself in the United States for his higher education.

Despite being based in Miami, famous for its party schools, Mohsin found himself making his way into an internship at CNN, where he got his first taste of journalism. Perhaps it was here in America, where the media industry is has hundreds of local media outlets, that Mohsin got the idea for local media networks in Pakistan. But it would be CNN that sent him back to Pakistan. When no journalist wanted to step into the country considering it slim pickings, the young intern raised his hand and made his way back home proudly wearing the CNN tag on his sleeve. It was at this point that he used the weight that came with the name of CNN along with his exceptional talent at networking to start making a place for himself in the news media business.

At CNN he was a producer, the cheap local labour that foreign journalists use to do their grunt work for them.. As CNN’s man in Pakistan, he played a number of roles, one of which was being the fixer. If a journalist from CNN wanted to come to Pakistan and interview the Chief Minister, Mohsin Naqvi would be the man that made all the arrangements.

He worked the phones, made connections and did his job well. He was never the man in front of the camera, but the field producer working behind the scenes – much as he prefers to run his organisation now. And all the while that he continued to make connections with people – rubbing shoulders with politicians, journalists, and the country’s elite. His affable nature and easy smile only helped him along the way as he continued to rise and make his way into the good books of people that mattered. He was quick to reach out for comment and always restrained, polite and constantly on his best behaviour.

In this time he grew close to a number of people, including Asif Ali Zardari, with whom he formed a much talked-about relationship. But perhaps the true testament to his networking skills was that he married into the Chaudhrys of Gujrat, one of the country’s most prominent political families.

For many speculating about the rise of C42, this seems to be the key link. The money must have come from his in-laws. How else could he have managed to pull this off and take such a huge risk?

But as people close to Mohsin reveal, C42 was completely his own doing. He came from a well-off family and had received a handsome inheritance. Using this, along with the haul of dollars he is assumed to have made during his time with CNN, at the age of 30 Mohsin Naqvi set out to launch his new channel. Despite all this, he still had to check himself with a certain level of austerity to make C42 happen. Ask him about how much it took to get the channel on its feet, Mohsin laughs and jokes people would break his head and call him a liar if he revealed how much he invested into C42.

But frugality has been a benchmark of his entrepreneurial ventures. For example, he claims that his City 42 Urdu newspaper was set up in just Rs 300,000, that too only because he had to buy furniture and printers. The newspaper also has the same innovative streak as the rest of his work. Not only does it have a unique size, he has also stopped selling it.

Back when the paper was first being launched, Mohsin had insisted that it be distributed for free. It was others on his team that had protested the move. Now they have finally adopted the original free distribution method he had originally wanted. To distribute the paper, he sends it to small locations where he knows it will be read. Normal targets such as the [Punjab] Secretariat and government offices have been ignored, instead Daily C42 is dispatched to small businesses and central hubs of the city.

His pay-off has been that he is getting small ads worth a lot of money from local, private advertisers. This makes him immune to being too dependent on government advertising, and also means the paper can bear its own expenses – a miracle in the current climate of Pakistan’s news industry.

His other projects have been similarly unique. UK44 is a channel for overseas Pakistanis in Britain which has seen some success. C41 has been a sister channel to C42 in Faisalabad, and Rohi TV is a channel focusing on the Seriki belt that Mohsin bought from Jehangir Tareen, though his first love remains the first channel he started.

But despite C42 being his personal favourite, perhaps his most ambitious undertaking was 24 News HD – better known as Channel 24. This was his dive into the national mainstream – but Channel 24 also had a very different concept. It would not have reporters stretched thin and jump into the already overcrowded news channel scene without an age. Channel 24 was going to be a current affairs channel, with news bulletins at odd hours and a greater focus on analysis and talk shows.

For this he hired some of the best anchors in the country, taking on board the most senior journalists to make a formidable team. It should have worked. After all, nobody really watches the bulletin from anywhere other than Geo or ARY unless they happen to be scrolling by a channel. It is the talk shows that people tune in for at a specific time.

But this was one concept that did not work out for Mohsin Naqvi. Advertisers did not take the channel seriously, giving it a B or C rating. The pressure for tickers and bulletins persisted as the ratings did not reflect the hopes of the team, and eventually Mohsin caved, converting the channel into a regular, run-of-the-mill 24 hour news coverage channel which is now scraping by as all other channels are currently doing.

To his credit, Mohsin saw when the time had come to pull the plug on his ambitions. He could have in the moment doubled down and persisted with his original model, which on paper should have been giving him returns. But the right thing to do at the time was to toe the line, and he did not let his ego get in the way of business. Another factor in the failure of the current-affairs model, of course, is that 24 News HD came out in 2015. While the news media industry had not started its final plumet, in which it is currently embroiled, the cracks had started to appear – and perhaps the time was just not right for an idea that otherwise seemed to work on paper.

But perhaps the biggest reason why Channel 24 did not work out as planned: it went against the rest of City Media Group’s business model, which has relied on highly localised that in turn appeals to a diverse, wide network of local businesses that have no other avenues to advertise their products and services. Channel 24, on the other hand, is reliant on the same government and large national and multinational corporate advertisers as the rest of the industry.

The state of the industry

It is a fascinating parallel. In 2009, Mohsin Naqvi had just launched C42 in very little money and naysayers laughing at him left right and center. The channel turned out to be a resounding success. Over the next decade, he would go on to launch three new channels, acquire another, and also release a newspaper. It is a meteoric rise to say the least.

But in 2019, much like the rest of the industry, he too stands on a ledge desperately trying to avoid falling into the abyss. This is despite the vast array of resources, new connections, and lessons at his disposal. There have been massive lay-offs in the news media world. During our informal discussion, he sighed and told us about how he was going to have to chop a third of his 1,800 employees. Soon enough after, Channel 24’s Peshawar bureau was axed and 600 people lost their jobs.

In our conversation, when asked about whether opening a news channel in the current climate would be a viable option, Mohsin Naqvi laughed, saying the person with the itch should prepare to throw a billion rupees down the drain.

“At this point no channel is making any money. We consider ourselves lucky if we can even break even,” he says. “Back when we started C42, it did so well that we got two people competing with us and opening Lahore-only channels a few years later. But by then, the situation was bad and they really haven’t been able to challenge us at all.”

Many have said that the media itself is to blame for the current situation. Much of the industry’s revenue was coming from the government, which was the largest advertiser in the country. For all intents and purposes, the media was being subsidised by the government, and this had allowed media tycoons to grow lax and let their media machinery become inefficient and clunky.

Overstaffed and underworked, newspapers and television channels allowed themselves to fall into a stupor which the government had to break them out of – a legitimate concern since ad expenditures by the government were ridiculously high.

But Mohsin is of a different persuasion. The news media industry is dominated by industrialists looking that founded channels so they could have a power tool. Today, a lot of them are regretting their decisions, lashing out at their workers and inefficient systems. Mohsin Naqvi is one of the few media owners who have worked as journalists, and as such, he understands the toll cuts and lay-offs take. “The work will suffer,” he says. No matter how bulky the news media machine may have been, it was still pushing out some good work. And with all the necessary cutbacks, the quality of the content is bound to fall.

“Back in the day I made money, serious money. Even from 24 I made a killing. Sometimes, City 42 would be doing better than all of the national channels.I won’t lie, the industry has been good to me. But currently? The situation is dire,” he says.

News channels are desperately trying to break even, crippled as they are by the lack of government ads, and especially with the ever looming threat of censorship breathing down their necks. Even as this piece was being written, on July 8, Channel 24 was reportedly taken off the air for covering the press conference and public gathering held by opposition politician Maryam Nawaz Sharif. Two other channels were also taken off the air.

With censorship on the rise and financial woes abound, one wonders what will become of news media in Pakistan, and whether even the entrepreneurial spirit and innovation will not be able to save it. And the business of it aside, that is a cause for concern in what is supposed to be the fourth pillar of the state.

You published great information. Great!

Media is supposed to be 4th piller of the state but unfortunately was run as business. Keep govts under pressure and extract the juice. This is not possible with Imran therefore they are suffering.

This channel doesn’t need government patronage as it has sold itself to sharifs. The stories they do are all shamelessly scandalous and brazen lies. They distort facts and are manipulative. Their ties speak the truth all too loud.

Comments are closed.