At a time when people should be staying indoors as much as possible and avoiding crowds, chances are that you recently found yourself waiting it out in long queues to try and get your gas tank filled, or driving around from station to station looking for one actually selling fuel.

In the middle of a global pandemic, flanked by a looming food security crisis and political turmoil, the last thing on anyone’s mind will have been whether petrol would remain available or not. With more and more employers calling for people to work from home, and people generally travelling less, should there not have been a surplus?

Pakistan’s energy sector works in baffling ways. While there have been numerous government inquiries regarding the fuel shortage crisis that has plagued the country, the findings have been far from ideal, not least because they suffer from a fundamental, structural problem: the entity conducting the inquiries – the federal government – is also the entity that is the single largest owner of assets in the energy supply chain.

How unbiased do we expect the bureaucrats who run the nation’s energy system to be? Do we really expect a report that says: “sorry, folks. This was completely our fault.”

Somewhat unsurprisingly, therefore, the government’s reports on the matter tend to be highly short-sighted, only explaining the immediate causes and consequences without addressing the deep-rooted structural issues. And never – and we really do mean never – do they ever seem to think that the government of Pakistan has done anything wrong.

Profit explains the fuel crisis, why the prices went down as much as they did, and what compelled the government to make them go back up again.

So why was there a shortage?

In terms of immediate causes, the general understanding has been that the government’s ban on imports along with a failure of companies in the oil industry to shore up their reserves is what resulted in the most recent shortage. However, there is much more to the recent crisis than just these factors, including allegations of cartelisation and curbs on smuggling.

In this article, Profit will attempt to lay out all of the competing explanations in a bid to determine which of them is the most persuasive in explaining how the system works and why it repeatedly breaks down with such frequency.

Ban on imports

The federal government decided to place a ban on the import of crude oil on March 26, 2020. Ostensibly, the reason for this ban was the massive dip in demand for petroleum products following the nationwide lockdown, this might have. Of course, this explanation makes no sense whatsoever. If there is a dip in demand, there will be an automatic dip in imports. The ban was not needed at all.

And of course, the government went ahead and made a bad situation worse by maintaining that ban for far too long. Permission to allow imports again was not granted until April 26, 2020.

Even then, the decision was made not because people were driving to commute more again, but because the harvesting season had arrived, and farmers needed diesel to get their tractors and threshing machines fired up.

However, what is interesting to note is that this ban was in place at a time when international fuel prices had seen an unprecedented fall. The fall had been significant enough that Profit ran a headline: “A barrel of oil now cheaper than a plate of chicken biryani.”

The headline was about the slightly cheaper US-based West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark prices, so it did not quite hold true in Pakistan, where we import Arab Light which follows the London-based Brent crude oil benchmark prices instead. However, the fact is that Pakistan could not fully take advantage of the fall in global prices. A barrel of Brent did not fall to reach the price of a plate of chicken biryani, but it did lay low for quite some time before heading back up.

While the government had banned the import of crude oil, “the supply of fuel was entirely dependent on local refineries,” explains Naeem Nawaz, an energy economist and research fellow at the Punjab Economic Research Institute (PERI), which rely on a combination of crude oil imports as well as domestic crude oil production.

According to Nawaz, the sudden decision to lockdown the country was bad enough for the petrol business, but ending it just as quickly made things worse.

“OMCs [oil marketing companies] were forced to cancel their international supply orders. The sudden decision to finish the lockdown across all sectors resulted in an exponential increase in demand followed by emergency purchase orders,” he adds. OMCs include companies like the government-owned Pakistan State Oil (PSO), Shell Pakistan, etc.

Reserves

Following the removal of the ban on importing fuel, all OMCs barring Pakistan State Oil (PSO) delayed the import of petrol and did not keep adequate reserves, or at least that is what the government and the state-owned PSO alleges. As with any allegations leveled by a company against its rivals, this one deserves to be taken with at least some degree of scepticism.

Ghiyas Abdullah Paracha, a leader of the All-Pakistan Petroleum Retailers Association (APPRA), said that the unnecessary delay in the import of petroleum products has inflicted a loss of billions of rupees to the government. This, of course, is a nonsensical statement since the government does not pay for petroleum, consumers do. But he is right that the ban on imports prevented the country’s oil industry from taking advantage of low oil prices.

PSO management claims that most OMCs did not maintain adequate reserves of petrol even after the ban on imports was lifted. Regulations and licensing requirements require OMCs to keep 21 days’ worth of fuel reserves at all times. However, PSO claims that other OMCs did not follow this requirement through in the month of April.

This created an artificial shortage. As a result, despite pumps remaining operational, regular petrol was not available. This resulted in people having to buy expensive High Octane Blended Component (HOBC) grade fuel.

Cartels

And then there is the explanation that the federal civil service favours: the idea that the shortage of petrol being artificially manufactured by private sector oil companies to create a petrol crisis within the country as a kind of pressure tactic. Yes, the same people who made the disastrous decision to ban imports think that somebody else is to blame. It is shocking, we know.

According to an inquiry conducted by the petroleum division of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources, nine companies were responsible for creating the artificial fuel shortage in the country.

Here is how their theory works. OMCs supposedly pressured refineries to reduce imports of crude oil by not buying their product and imported refined products instead. In the civil service’s telling of the story, the oil companies somehow did not import motor spirit (better known as petrol), the most widely used fuel for vehicles in Pakistan and instead only imported the higher-cost HOBC.

This left no regular petrol available, and only the refined or ‘high octane’ kind, which consumers were then forced to buy. Of course, this theory seems to not understand the difference between revenues and profit margins nor elasticity of demand, assuming that a product with a higher margin (HOBC, in this case) will result in higher overall profits for the oil companies, even though the revenue fall from not selling the fuel that most of their customers need would likely more than wipe out any higher margins from HOBC.

Back in June, while the price of petrol was down to Rs75 per litre, HOBC was available at Rs155-160 per litre depending on the brand or retailer. As a result of the shortage, there were reports of consumers having to purchase HOBC instead of regular petrol in case of emergencies, even motorcyclists. The government report seems to believe that this was the agenda of the private sector oil marketing companies all along: that they wanted to sell this higher margin product and create a shortage of the more widely used motor spirit (petrol) in order to pressure the government to adopt policies that favour the industry, in particular price deregulation.

How credible is this theory? Well, it shifts the blame away from the government, which must be highly convenient for the civil servants who wrote the government’s inquiry report. After all, if it was not the private sector oil companies that caused the problem, somebody might start asking about what role the government’s decisions had in the matter, and might ask the people who made energy policy decisions on the government’s behalf. People like the civil servants at the petroleum division of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources.

Reality, of course, is far more complex, and while it is true that the private sector oil marketing companies had lower imports than needed, they were hamstrung by highly rigid pricing regulations (which we will turn to below).

Control over illegal smuggling of petrol from Iran

Petroleum Secretary Asad Hayauddin recently explained to the Lahore High Court that one of the reasons behind the shortage of petrol in Pakistan was the stricter controls at the Iran-Pakistan border after March 19, 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic – which hit Iran particularly hard – caused the government to adopt stricter controls at the border between the two countries. It had the unintended side effect, however, of making it harder for Pakistani and Iranian petrol smugglers to move cheap Iranian petrol into the Pakistani market.

But while the petroleum ministry has been pushing the idea of a stricter enforcement of border controls as a reason for the petrol shortage, this explanation is somewhat unpersuasive. In his testimony, Hayauddin said that the government estimates that approximately 1.2 metric tons of petrol had been smuggled through this corridor into Pakistan on a daily basis.

Of course, this is a patently stupid. Iran only produces 0.6 million tons of petrol a year, and if Hayauddin is to be believed, Iranian smugglers somehow managed to smuggle twice as much as Iran’s total oil production into Pakistan.

Let us be charitable and assume he simply meant every year, and not every day. That would mean that oil imports from Iran account for approximately 4% of Pakistan’s total consumption of about 27.7 million tons a year. That is significant, but nowhere remotely close to enough to explain the shortages being experienced by the country.

So why is the government putting forward such a weak explanation? Surely it is just plain coincidence that this happens to be an explanation that makes the government look good: “Look at us, we are so effective at our job in cracking down on smuggling that it is creating an actual shortage of petrol!”

Politics

To their credit, of course, PSO did perform relatively well during the fuel shortage. At times, PSO pumps were the only ones in many parts of the country that were able to sell petrol, whereas many of the other companies ran out of petrol.

In an advertisement, PSO even celebrated supplying 20,500 metric tons of petrol from Karachi in a single day, which is a record high for the company. And on June 1, 2020, PSO was able to sell an upward of 48,000 metric tons of petroleum product, which is approximately equivalent to the amount of petrol in a vessel.

It does make one question how PSO was able to undertake preemptive measures. Did they know that OMCs would be making this “mistake”? Is this why PSO shares rallied in May?

One reason the other companies failed to act may have been complacency following a significant run of success in gaining market share. Back in 2010, PSO accounted for nearly 70% of the oil market in Pakistan, whereas in 2019, PSO accounted for approximately 45% of the market. However, after the shortage, PSO, being the only OMC providing petrol, was able to see a manifold increase in sales.

Domestic petrol prices: explained

The reasons explained above are all short term causes that explain the current shortage. However, there is something fundamentally wrong with this sector’s pricing mechanism, which impacts the entire sector structurally. This is why it is vital to understand the details of all the components that end up giving us the price of petrol.

Components of the petrol price

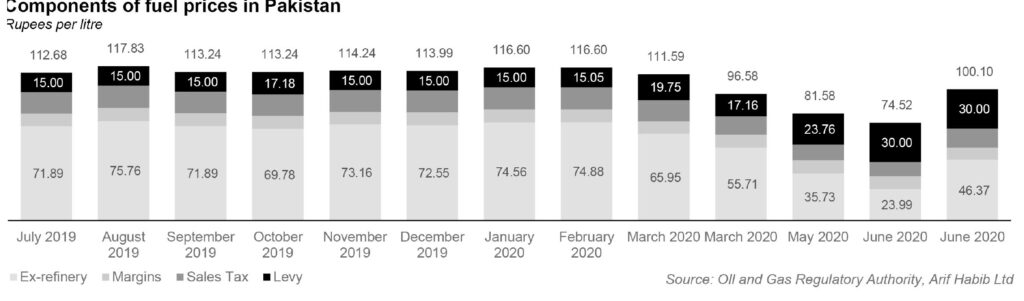

The price of petrol has various components that combine together and are totaled to reach the ex-depot price, or the price the consumer sees at gas stations.

The base price is the imported price, in the case of oil imports, or the ex-refinery price in the case of domestic oil production. On top of that, there are retailer and freight costs which include the inland freight equalisation margin, OMC profit margins (what PSO, Shell, etc. earn), and dealer commissions (what the petrol pump owners get to make). Lastly, comes the taxation which includes general sales tax and the petroleum development levy.

The ex-refinery price is the price at which refineries can sell their fuel to OMCs and the price at which importers can sell distillates within Pakistan. One of the first additions that happens to this initial pricing are the commissions that retailers and dealers receive.

The next significant addition is the Inland Freight Equalization Margin (IEFM), which is the cost of inland movement incurred by a refinery for the transportation of crude oil from the source to the refinery. It also includes the cost incurred by an OMC while transporting the finished product to various depots across the country. This basically includes all transport costs within the company.

The purpose of this margin is to establish and maintain parity in the prices of fuel throughout the country. The money collected from this margin goes on to create a pool. The government then uses this money from the pool to provide indirect subsidies to Pakistanis to ensure the same price of fuel is found throughout the country.

Basically, if this subsidy did not exist, petrol prices would be cheaper in Karachi and more expensive in almost every other part of the country, and especially expensive in Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan.

After all of these pricing tools, we finally come to taxes, because the last two additions to the price the consumer sees at the gas station are the general sales tax (GST) and the petroleum development levy.

The GST, as of late, is set at 17%. Keeping in mind that it is a ratio rather than an absolute number, it varies with a change in the price of petrol. The levy, on the other hand, is a surcharge and set as an absolute rupee amount per litre, though the government does vary how much it charges under this tax relatively frequently.

It is used as an instrument to bring about stability in the price of petrol by offsetting the impact of drastically changing import prices and costs associated with fuel. The levy, however, is often seen as a political and fiscal tool to either pass on ‘relief’ to consumers during an election year or to generate more revenue in other years. Previously, the levy was priced at Rs15 per litre but it has now been raised to Rs30 per litre.

This means that when the government wants to pass on relief to consumers it could keep a levy of zero rupees or some low number. Essentially, this means that after all the costs are added, the government could increase the price of fuel up to Rs30.

Problems with the pricing mechanism

The fundamental flaw within the market is the pricing structure, which has many, many problems that oil marketing companies dislike and energy analysts believe renders the market inefficient.

“Import cost, which is the basic component of the price is determined on the basis of the purchase costs of PSO. This is done by taking a monthly average of cargoes imported by PSO irrespective of whether the purchase cost of other OMCs is higher or lower,” Naeem Nawaz explains. “Ideally, the base component should be an optimal representative, or an average of the import prices experienced by all OMCs.”

Considering the change in market dynamics, Nawaz feels that this is crucial. “One must keep in mind that PSOs share within the market is shrinking as the number of market players have increased from 12 to more than 50 within the last 7 years.” The fact that PSO’s share has shrunk explains that PSO should no longer determine the prices for everyone.

But then comes an even bigger flaw in the system: prices for oil products are reset by the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA) only once a month.

When prices are trading within a narrow range in the international markets, this tends to not matter. The calculated price of petrol in the country reflects the trend in the markets around the world. This is also due to the fact that the import decisions by PSO are spread throughout the month and do not have to deal with import bans.

However, when there is turbulence in the international market, the mechanism shows its structural weakness because the ex-depot price, or derived price does not depict the changes in the international market fast enough, which then creates financial problems for oil companies.

If you look at the international market, the prices in the Gulf Arab states had been adjusted to near $40 per barrel as a result of the OPEC supply cuts. “The local price of petrol, however was set at $23 per barrel, exceedingly less than the purchase price of OMCs, which is a prime reason OMCs tried to manage a cut in supplies to control their losses,” says Nawaz.

This was not the first time Pakistan faced a fuel shortage. In the past, most shortages had been a result of an actual shortage of fuel in the country and had less to do with OMCs refusing to sell at lower prices. But the logic is the same: if my cost of buying a product is less than the price I am allowed to sell it at, why would I sell? Why should the oil marketing companies buy oil at $40 a barrel and be forced to sell it domestically at $23 a barrel? Why would anyone do that?

This flaw – and the fact that it consistently leads to petrol shortages in the country – would suggest that revisiting the price mechanism could ensure such problems never emerge. This then begs the question: why are the prices of fuel even regulated in Pakistan in the first place?

Mohammad Wasi Khan, Director at Byco Petroleum Pakistan Limitedsays, “”Deregulation is the solution. If done in a controlled manner the flaws in the system could be fixed”

Regulation: fetish of the control freaks

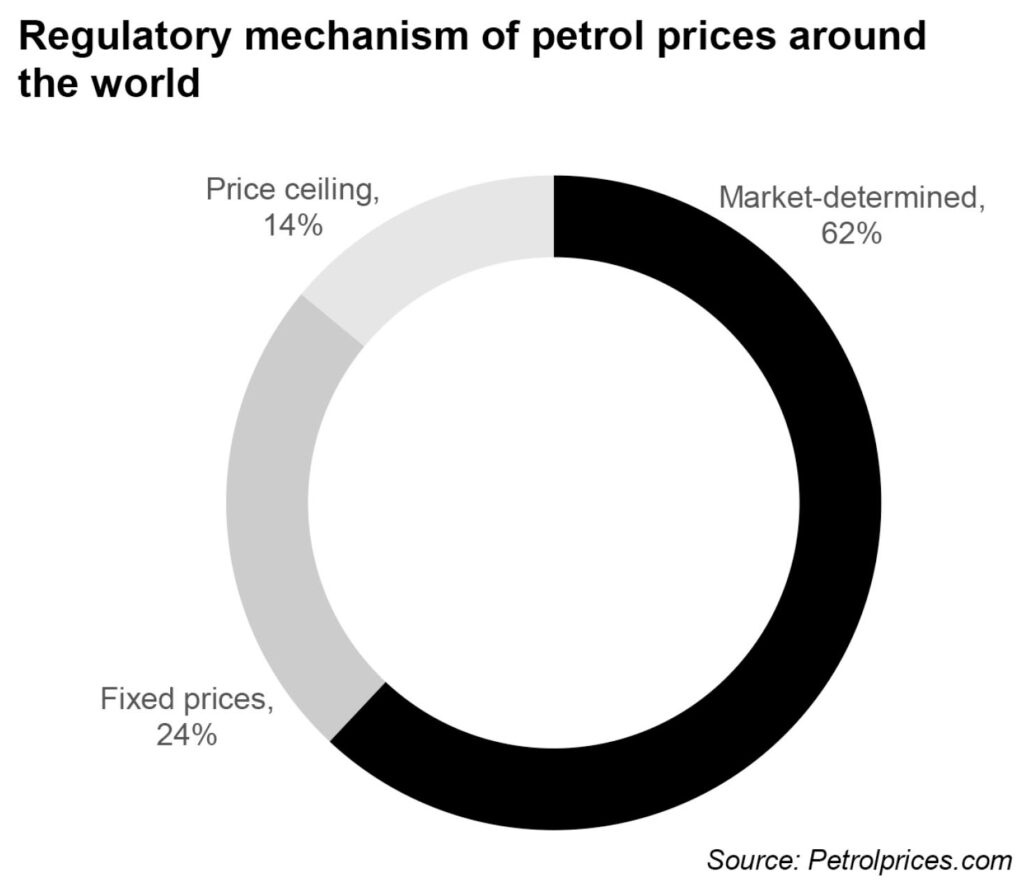

Different countries around the world determine the local prices of fuel in different ways. These prices could either be market-determined, fixed, or with the implementation of a price ceiling. The extent of intervention, however, depends on government aims and fuel market characteristics.

Market determined prices are typically found in more liberalised markets where state intervention in the fuel market is usually restricted to defining terms and conditions and ensuring free competition. In such a market, retailers determine their prices freely and prices of fuel could be different for retailers, regions, cities, or even individual pumps.

Price ceilings, on the other hand, is a form of regulation where the government sets a maximum price for fuel. Retailers, however, are allowed to set their selling prices at any price below or equal to the price ceiling. The government revises the maximum price periodically. This acts as a shock absorbent that protects consumers from sharp advances in the price of oil, or cartels keeping prices higher than they should be.

The strictest form of regulation, however, is when the government decides to fix the price retailers are allowed to charge. This means all retailers charge the same price regardless of their costs.

Regulation trends around the world

According to GlobalPetrolPrices.com, an energy data provider, out of 97 countries, 24 countries implement a fixed price mechanism. Pakistan, along with countries like Sri Lanka, South Africa, Egypt, Indonesia, Malaysia, Kuwait, amongst many more are examples of these countries. Fourteen countries have set price ceilings, while the remaining 59 sport market-determined prices.

This means that nearly 62% of the reviewed countries have a liberalised fuel market. Most of these are towards the top of the economic development list such as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, many European countries, the United States, and Canada, amongst many more.

The remaining 38% of countries reviewed have some sort of regulation. While some of these countries include both highly developed countries and less developed countries, an interesting fact is that a number of OPEC and oil-producing countries form these regulated markets. This is done by the government to control the retail fuel market through subsidised retail fuel prices.

About 24% of the total or approximately 60% of the regulated countries have fixed prices, like Pakistan. The question, however, is, why does Pakistan regulate domestic fuel prices? After all, it is not a producer and there are no subsidies. In fact, the government offers the opposite of a subsidy by taxing the public excessively in the form of petroleum development levy, and of course, through general sales tax.

OGRA, being the regulatory authority, has a mandate to advise the government about the prices based on the approved price formula. The final decision, however, is made by the government. The Prime Minister, or at the very least the finance minister, are the ones that decide the price considering the impact it has on revenue collections.

It says something about governance in Pakistan that decisions as minute as “what price should we sell petrol at this month” are made at the level of the Prime Minister.

So why does Pakistan regulate fuel prices?

Profit reached out to the spokesperson at OGRA to enquire why the regulatory body decides the fuel prices. The spokesperson simply claimed that the prices are, in fact, deregulated. While it could be said that he is lying through his teeth, we will give OGRA the benefit of the doubt and say they are only partially and technically correct.

The prices of 97 Research Octane Number (Ron) are deregulated. However, the petroleum most commonly used throughout the country, i.e. 92 Ron which is Euro II (upgraded from 87 Ron in 2016) is nor deregulated. That is why you see the same price of regular petrol everywhere.

“Even if the price of petrol was not regulated, the sales tax and petrol levy are to be decided by the government,” explained Nawaz. Thus one could say that even with deregulation, the government still has significant control over the price of petrol. Some even say that the current pricing mechanism allows the government to meet any budgetary shortfalls.

Some energy experts call for the taxation on fuel to be defined and fixed once in the budget, altered only under extreme conditions or out of absolute necessity. However, rather than answering why Pakistan regulates fuel prices, let us see why it does not deregulate.

“First and foremost,” Atta Ali Malik, Partner at financial advisory firm CMC says, “we are not major players in the international market. Considering a large portion of our import bill is based primarily on the import of fuel, it makes sense for the market to be regularised. This also helps the government control supply and demand.”

The removal of IFEM could deregulate prices, at least between cities. However, the reluctance of the government from doing so is primarily because the rural users would be at disadvantage compared to urban users.

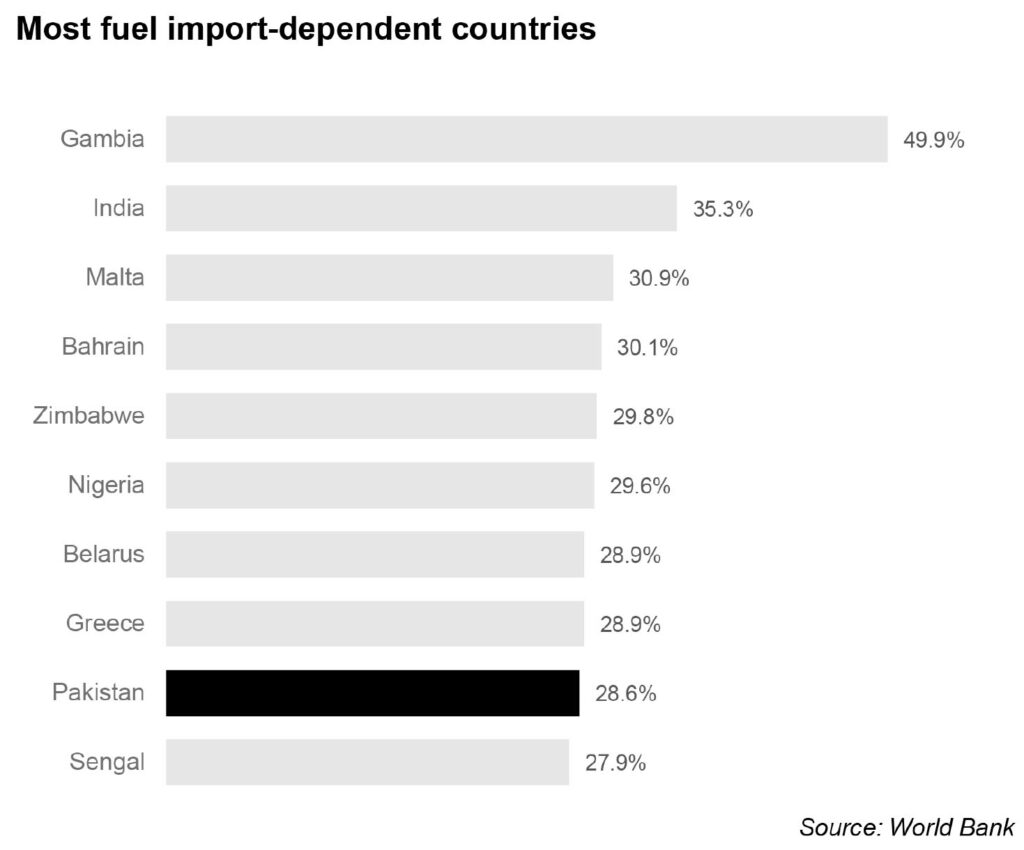

Pakistan is a net borrower in terms of fuel. In fact, the share of fuel imports as a percentage of merchandise imports is one of the highest in the world. A majority of the fuel that is used to meet local needs is imported, refined locally and then sold.

“The oil market in Pakistan is not at a level which is mature enough to compete. This essentially means cartels of OMCs are likely to plague the market resulting in the exploitation of consumers,” notes Nawaz.

He adds, “The emergence of cartels is essentially a problem for a country like Pakistan considering how consumer rights protection is not efficient.”

Experts believe deregulation will only be fruitful if the prerequisites are available. A step towards that would be revisiting the existing pricing structure and addressing the flaws. However, no one is exaggerating about the emergence of cartels. One look at the cartel in the 97 Ron market, or commonly known as HOBC, shows how strong these cartels really are.

Prior to 2016, the price of HOBC was regulated. HOBC was produced by PARCO refinery only and was sold at a regulated price, primarily by PSO. However, in 2016 under then-Petroleum Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, OMCs were allowed to market 97 Ron under different brand names within a deregulated environment. These are the Shell V-Power, PSO Hi-Octane, etc. that we see at pumps.

“The idea was simple, to pilot the deregulation. The market for 97 Ron, however, is very small. Despite that, the current cartel in the prices shows how in light of today, the idea has failed,” claims Nawaz.

The evidence for this? The fact that the premium between HOBC and motor spirit used to be much lower before deregulation than after deregulation. In fact, the difference is stark. The price differential between HOBC and petrol is approximately 88% as per a survey conducted by Profit on 19 May 2020. However, prior to deregulation, the difference between the two averaged at 7% throughout 2016.

This makes one question that if the government cannot control cartels within a small segment of the market, how would they counter a larger one? Essentially, the primary problem is the immature market structure. Regulation here somewhat makes sense. But why are the fuel prices decided on a monthly basis?

“Some countries allow retailers to determine their prices on a daily basis. That is not possible in a regulated environment like ours, especially where 5 or 6 cargoes of 55,000 metric tons each are enough to meet the demand in addition to the locally refined product,” explains Nawaz.

“We’ve tested the model of announcing prices on a fortnightly and then on a weekly basis in 2013 during the PPP government. It has failed in Pakistan. It was taken as an additional source of uncertainty.”

However, Khan believes “The decision to move to a monthly decision is bad for the market considering that fluctuations in the market accumulate. This adds pressure onto the next month. If prices were decided on a fortnightly basis, the impact would lower. In fact the optimal choice for the market would be to decide on a daily basis”

Interestingly enough, the government, in 2017 feared irregularities in the market. When the government introduced 92 Ron, some quarters of the industry asked for three different quantities, 82, 92, and 97, similar to India. This gives consumers the ability to choose a grade of petrol based on their purchasing power.

However, due to the fact that consumers would seem hesitant and uneasy over whether they were indeed getting the grade they were paying for, the government decided against it. The prospects of cheating consumers would not be new. It is no secret that some smaller players have mixed jet fuel, benzene and kerosene with petrol in order to overcome the “losses” they have incurred owing to taxation and the price differential (levy).

Recent fuel price decisions: explained

Over the course of this fuel crisis, two major points have been when the government first decreased the prices of petrol and other fuel products. The move was celebrated as a victory by the government, but it did not last long since prices went up again drastically after the OMCs refused to comply. So what exactly was all this about?

The initial price decrease

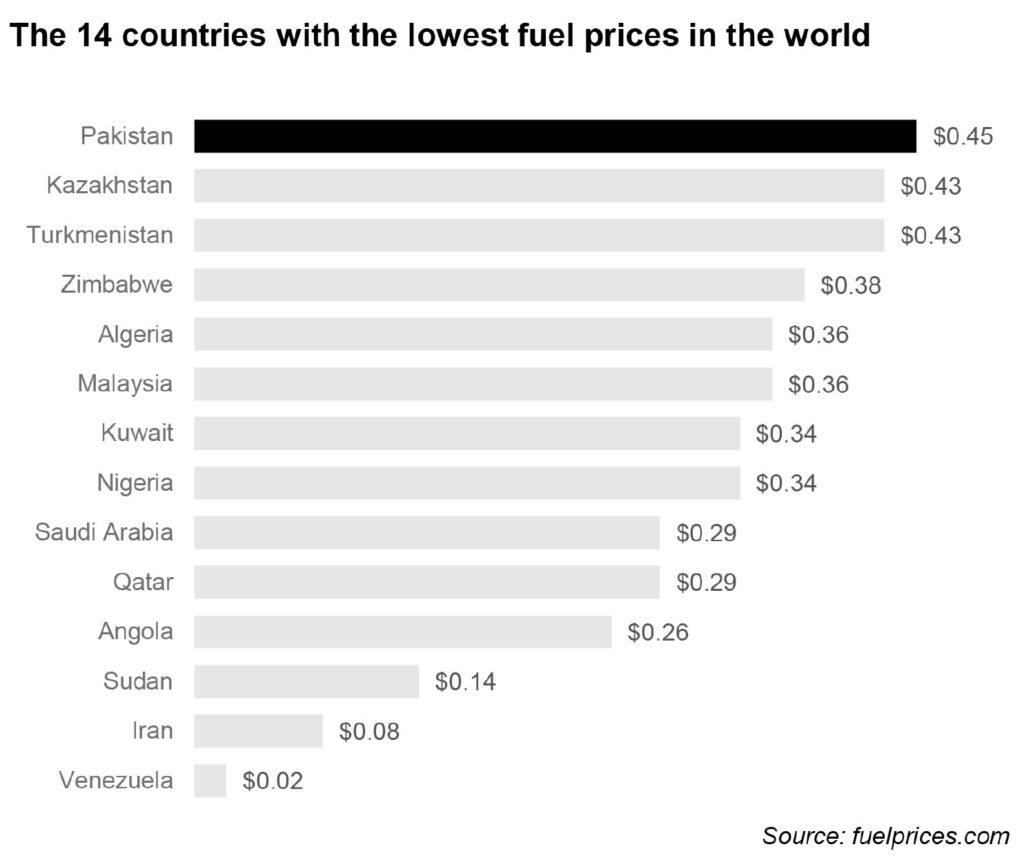

The government decreased the price of fuel by Rs7.06 in June 2020 following a Rs15 decrease in the month of May. Prime Minister Imran Khan claimed this as a great victory, tweeting that Pakistan now has “the cheapest fuel cost compared to other states in South Asia. India is almost exactly double.”

However, to take credit for this fall in fuel prices was a great misrepresentation on the part of the government. You see, the government increased the levy to its maximum of Rs30. How did the government manage to increase the tax and still decrease prices? By making the oil companies take a price cut.

Basically, the government is forcing the oil companies to run tens of billions of rupees in collective losses in order to finance the government’s budget deficit. Needless to say, the oil companies were absolutely livid at the government for having done so and were in no mood to cooperate when the inevitable fuel shortage arrived.

So why did the government increase prices?

Having monumentally bilked the oil companies and causing the petrol shortage, the government then had to do something in order to make it up to those companies or else risk the shortage continuing. That, more than anything else, is why it decided to raise prices by a whopping 34.3% in late June, to Rs100.10 per liter. Basically, through this price increase, the government is covering the losses it had caused the oil companies in May and June through higher prices in July.

How does that make any sense? What good is trying to control a market if your control keeps causing the market to break down and crash? Khan notes, “Deregulation is the solution. If done in a controlled manner the flaws in the system could be fixed”

The government also needs to introspect whether its priorities with fuel prices are appropriate. Fuel prices in Pakistan have predominantly become a political decision rather than a market-driven signal. But if we are to remedy the situation, there needs to be some serious introspection at the Petroleum Ministry and the cabinet.

Why do we celebrate the lowest fuel prices in the region? Why does the government not have an adjustment variable in the fuel prices that could help smoothen the price of petrol over a period of time? Why do we encourage a greater carbon footprint through lower fuel prices? Why is the price of petrol equated with the ego and popularity of whoever is Prime Minister?

Additional reporting by Syed Masooma & Hassan Naqvi

when prices are low they can take credit for it. it can be used to score political points

it also gives the impression that they are doing something for the people. it’s easier to hold large meetings to set the petrol price than make actual reforms. there isn’t enough room in the budget for reforms anyway.

if they deregulate prices and also allow imports then there may still be shortages from time to time until the market corrects itself but crucially it will not be our leaders’ fault. conversely when things are going well they won’t be able to claim credit for ensuring cheap and smooth supply of fuel!

Khoobsurat analysis