Who would have thought that it would be ride-hailing, of all services, that would get Pakistanis used to the idea of spending money over the internet? Entrepreneurs and companies have been trying their hand at e-commerce in Pakistan for at least a decade now, but it took the arrival of ride-hailing giant Careem in Pakistan to get people used to the idea of paying for services or goods that they bought over the internet.

So, if you are Careem, and you have just achieved what was – in the Pakistani imagination – considered almost impossible, it would be downright irresponsible not to take it one step further and try to grow and capture as much of the e-commerce market in the country as possible. That seems to be the idea behind Careem’s launch of its super-app – something that Careem founder Mudassir Sheikha has been talking about publicly since at least early 2019 – which launches for the Pakistani market on Monday, June 15.

Here is how it works: Careem has already created the infrastructure that allows people to use its ride-hailing services and pay for them through the app, either through payment information stored in the app – such as a debit or credit card – or through credit that they have added into their Careem wallets by paying cash to the drivers (known as “captains” in Careem parlance). Why not use that infrastructure – both the app and the payment mechanism – to get people to pay for other goods and services that they may currently be buying through other apps?

“Super App by Careem will be like a virtual mall, where there will be two models – services owned and offered by Careem itself (ride hailing, food, same-day-delivery capped at Rs5,000, and payment from CareemPay), and other third parties on board offering any sort of services that need communication of the vendor to the customer base,” said Zeeshan Baig, CEO of Careem Pakistan, in an interview with Profit.

“The third-party vendors [marketplace] will begin to unroll towards the end of the current year or early next year,” he added.

The move towards building a super-app is the latest evolution in a business that has had to undertake a gargantuan effort in getting its target markets used to the concept of its services and building a sustainable business. In this story, we take a look at how Careem has evolved in Pakistan, and how the super-app is likely to build on the features the company has been able to add onto its platform in the four years that it has been in operation in the country.

For this story, Profit was given exclusive access to Careem’s internal data, which provides a never-before-seen look at how this business has changed from when it opened its doors in Pakistan in 2016.

Building a market out of thin air

Careem started off in 2012 as an app that simply provided access to existing cab and limousine services, initially in Dubai and then in other cities around the Gulf Arab region. It always had the ambition to become the region’s answer to Uber (which ultimately bought the company in early 2019 for $3.1 billion). But it was operating in a region that was very different from the United States, the home market for Uber.

Uber had started off in 2009 in the middle of the biggest recession in nearly 80 years in the United States. It was a unique moment in a unique country. The US at the time had three key ingredients that allowed Uber to succeed:

- A large workforce that was out of work at the time and actively looking for sources of income

- That population owned, or otherwise had access to, cars

- They, and the wider US population, had access to both smartphones and 3G/4G mobile broadband internet connections.

Of those conditions, the United Arab Emirates market had two of the three: plenty of people in the UAE are there for all sorts of employment, and by 2012, smartphones and mobile 3G connections were widespread in the region. What it did not have – at least at the start – was the second factor: in the UAE back then, there was a disconnect between the people who owned the cars, and the people who would be willing to drive them around for an income.

Careem bridged that initial gap by partnering with existing rental car and limousine services, and extensively marketing its services to customers, proving its ability to connect cars with riders. Once it was able to demonstrate that it could do that – and do so profitably for the drivers and car-owners – it then branched out to allowing owner-drivers to offer services on its platform as well, which was the initial plan all along.

Something similar happened in Careem’s evolution in Pakistan. The company waited to launch in Pakistan until 2016, around the same year that 3G and 4G connections started becoming widely available in the country. And when it did so, it partnered with car rental companies or with small business owners who would be willing to own multiple cars and hire salaried or fare-sharing drivers to operate them on the platform.

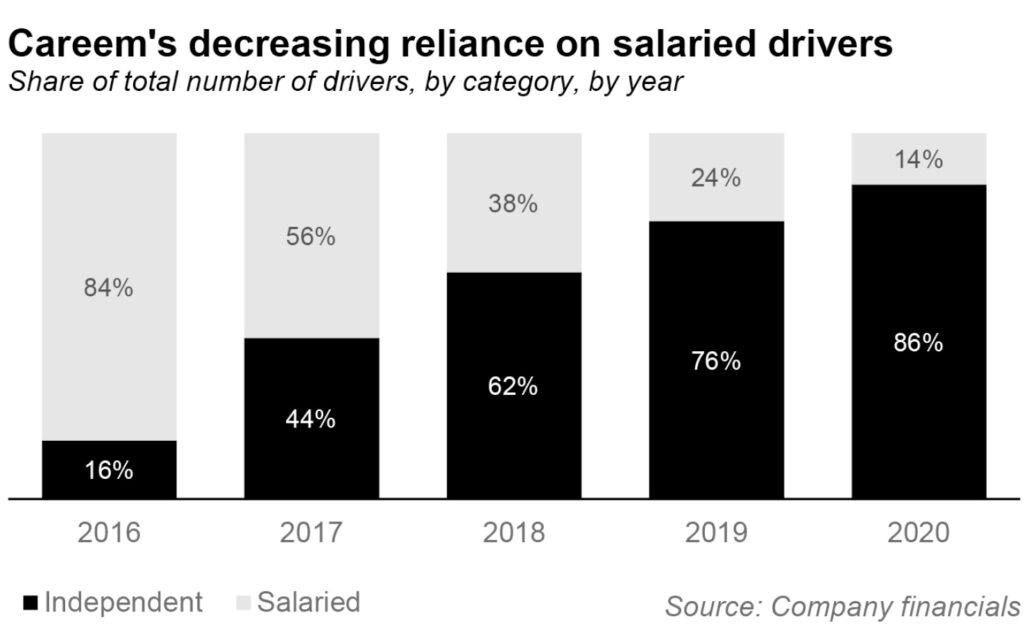

In 2016, according to the company’s internal data, about 84% of the cars on its platform were driven by drivers who were salaried employees of a car rental company or other small business that had signed onto Careem. Only 16% were people who owned their own cars. This model got the company off the ground, but it had its limits.

“When we started operating here, the easiest thing for us was to go to rental companies and offer them our platform,” said Baig. “They already had the fleets, drivers and everything. But that model means a lot of shares to lots of parties. The margins are already low in this type of work and that model further diluted it.”

Needless to say, Careem wanted to move to a business model more similar to that of Uber in its mature markets, and that meant spending intensely in order to grow, offering artificially low fares to customers and bonuses and all sorts of other cash incentives to drivers.

“As with any startup and anywhere in the world, in the initial days there is the ‘buying growth’ phase,” said Baig.

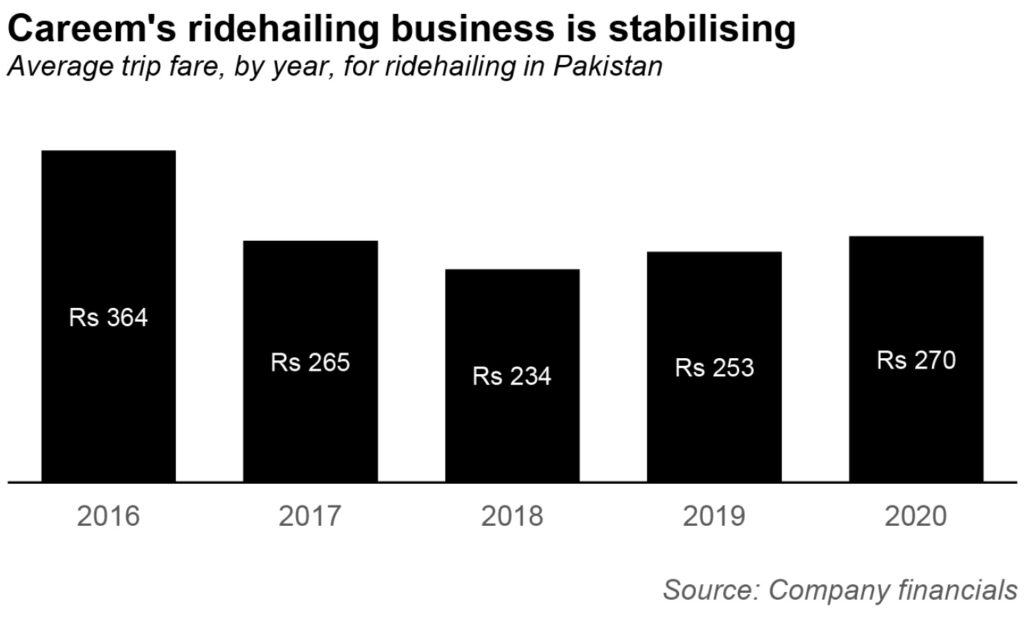

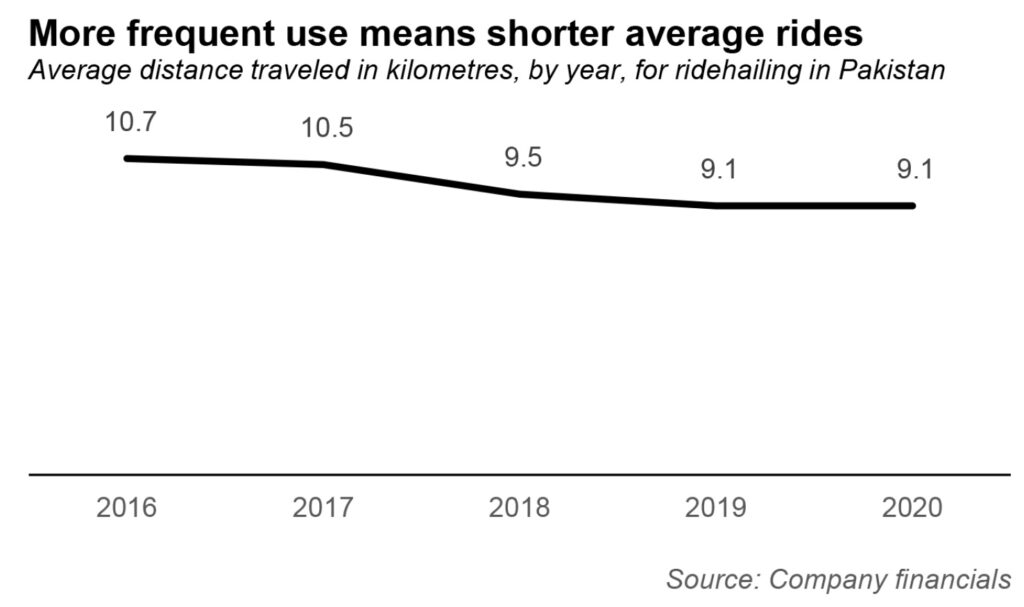

And Careem was aggressive in its effort to buy that growth. Between 2016 and 2018, average fares per ride for its ride hailing business went down by 35.7%, from Rs364 per ride on average, to just Rs234 per ride. And this was not driven by people using the app for shorter rides: while the average distance traveled did decline somewhat – from 10.7 kilometres in 2016 to 9.5 kilometres in 2018 – the bulk of the difference came from a 27.6% reduction in average fare per kilometre, which went down from Rs34 per kilometre in 2016 to Rs24.6 in 2018.

Drivers during this time, meanwhile, kept getting higher compensation to continue driving on the platform so that there would always be enough cars for people whenever they needed to hail a ride. In other words, Careem did not care if it made money on each ride. It cared about the total number of rides, the number of customers, and the number of drivers using its platform, and it was willing to spend the money to get them.

That growth strategy – termed ‘blitzscaling’ by LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman (blitz is German for lightning) – does not come cheap. In the first four years of the company’s operations in Pakistan, Careem has invested $85 million in this market, the bulk of which has gone towards that blitzscaling strategy of ‘buying growth’.

It did work, however. By the end of 2019, Careem was the largest e-commerce business in Pakistan, by a wide margin. During a year when Daraz was doing close to $50 million in annual revenue, Careem was handling closer to $250 million in annual bookings, according to sources familiar with the matter.

(The company’s management did not confirm these numbers. While they shared many data points about their operations, they were not willing to discuss revenue or profitability numbers.)

More importantly from the company’s perspective, the growth came as a result of more independent drivers signing onto the platform. By 2018, well over half of the drivers on the platform – 62% to be precise – were independent drivers who owned or leased their cars. That number has since grown even higher to 86% as of early 2020.

“It makes more economic sense to have independent vendors with their own cars to work with us,” said Baig. “From the quality point of view as well, a salaried driver has less opportunity cost when it comes to being efficient and following rules.”

Having more independent drivers also lowers Careem’s own operating costs in Pakistan. “We used to manage vendors very strictly when we had more salaried drivers, but with independent vendors with their own cars and own investment, they are more motivated as well. So, this model also means better cars, better services, and obviously makes more economic sense,” said Baig.

The platform now has 150,000 monthly active drivers across Pakistan, according to Careem’s management, out of 700,000 registered drivers, a number the company hopes to grow aggressively.

“The goal is to reach the number of 1 million [registered drivers] by the end of 2020,” said Madiha Javed Qureshi, Careem Pakistan’s spokesperson, in an e-mail to Profit. “Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad happen to be our main centres.”

Growing the business… and profitability

After Uber acquired Careem in early 2019, the company was able to begin taking away those incentives for drivers and raise fares for customers. The average fare per kilometre rose 12.9% in 2019, and by another 6.7% in 2020. While those increases are roughly in line with inflation for both years, it does represent a shift in Careem’s business: it no longer needs to spend money to convince users to start using its core ride hailing services and can raise prices in line with costs.

The change in approach has not gone unnoticed by both riders and drivers. Many riders have noticed the rising fares, and drivers complain that the bonuses and other incentives that they used to get, and expected to continue getting, were no longer available to them, attributing the change to the Uber acquisition, which has significantly reduced competition in the Pakistani market for ride hailing services.

Management, however, believes that it was time to make those changes, and insist that the Uber acquisition has not shaped their decisions on this matter.

“At some point, businesses need to start making economic sense,” said Baig. “We consider both the captains and customers when we make our model, and our pricing is done after including fuel prices and other cost factors for captains so they can still earn from it, and then that pricing is offered to customers. The discontent comes when businesses move from buying growth to actually running a business. But we are confident that our model is still efficient for both captains and customers and they will stay on board.”

Yet while the management sought to downplay concerns around competition, the government did not share that view. In approving the merger, the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) placed several conditions on Uber. These include a “no contractual exclusivity” clause to ensure that drivers can continue to offer their services on any platform of their choosing. It also capped Uber and Careem’s service fee at a maximum of 27.5% to ensure that it could not use its monopoly power to decrease drivers’ earnings. And it even capped the surge prices at no greater than 2.5 times normal fares.

All of these conditions limit the extent to which Careem and Uber can use their combined market dominance, with limits on prices charged to both riders and drivers. These limits are set to stay in place for three years, or until another ride hailing service enters the market and gains at least a 25% share of the market, or if multiple competing ride hailing companies enter the market and collectively gain a 33.3% share of the market.

Of course, this was all before the pandemic.

Covid-19 strikes

At some level, the business suffers from both bad luck and good timing. Just as Careem’s business in Pakistan was stabilising and had achieved sustainable scale, the coronavirus pandemic hit the country – and much of the world – earlier this year, dramatically reducing the need for mobility by most of Careem’s customers. Worldwide, Careem’s business declined by 80% during the month of April, causing the company to lay off a large portion of its employees.

“There is no easy way to say this, so I will get straight to the point: starting tomorrow and for the next three days, 536 of our colleagues who make up 31% of Careem will leave us. We delayed this decision as long as possible so that we could exhaust all other means to secure Careem,” wrote Careem founder and CEO Mudassir Sheikha in an e-mail to the company’s staff in early May 2020.

Careem caught its fair share of flak on social media forums for making this unpopular decision. But as difficult as this time has been for many businesses – including Careem – it also represents an opportunity to streamline operations (nothing like a crisis to make you realise about which job functions you can do without) as well as more keenly look for new revenue opportunities.

In the case of Careem, that new revenue opportunity has been the delivery business. In 2017, Careem acquired the Karachi-based startup Delivery Chacha, and fully integrated it into its operations by 2018, allowing it to diversify its revenue streams.

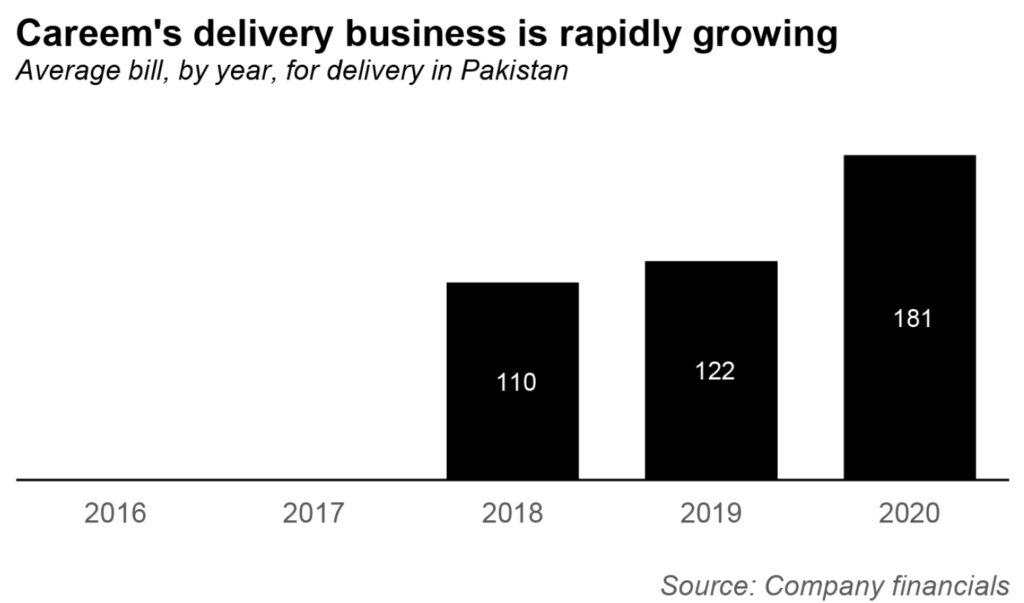

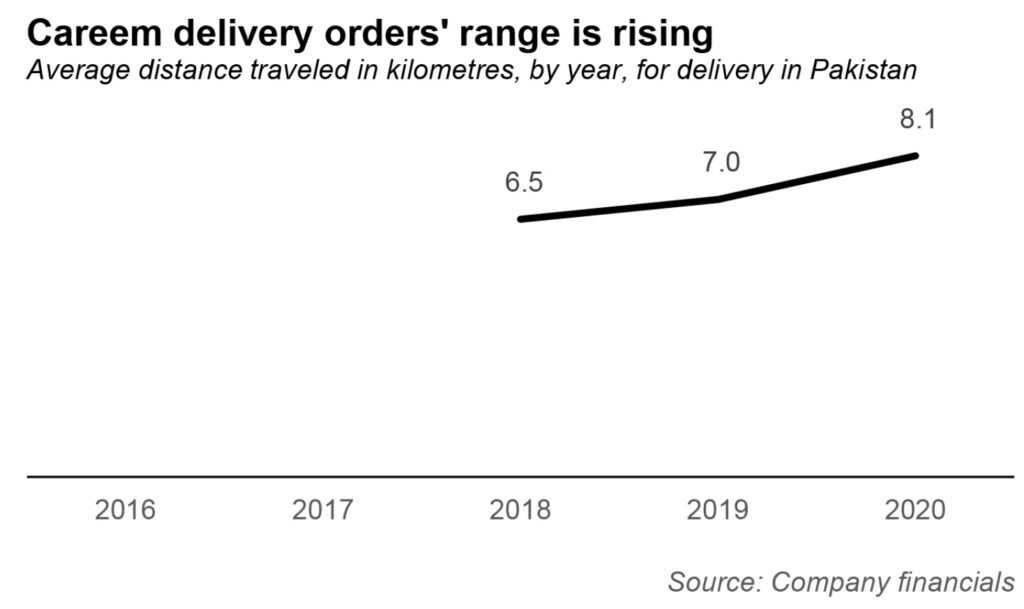

Delivery revenue, however, did not seriously start growing until earlier this year, when it skyrocketed. The average fare per delivery rose from Rs110 in 2018 to Rs181 in 2020, an increase of 65% in just two years, helped in part by the fact that the app now does more than just restaurant delivery.

“The current Covid-19 crisis made the demand for home deliveries shoot up by a great deal. Careem thought it was a prudent time to enter into the delivery business – food and other deliverables,” said Baig. “The lockdown and the conditions changed consumers’ behaviour significantly and it was the right time to start these extra services.”

In other words, this was as good a time as any for Careem to launch its super app.

The super-app pivot

The tech world has been obsessed with the idea of a super app ever since Tencent’s Weixin (known internationally as WeChat) hit more than half a billion users in China in 2014. WeChat is the ultimate super app. It combines social media, messaging, maps, mobile payments, e-commerce of all sorts, all into a single app. In Pakistani terms, it would be as though Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Google Maps, Daraz, and EasyPaisa were all a single app.

Veon, the parent company of Jazz, had high hopes of launching Pakistan’s first super-app, but the app tried to add too many things too quickly that it died before it ever got off the ground.

Careem, however, is different. Unlike Jazz, it already has a relationship with its users where they are used to paying for its services online, through their Careem wallets. And it is launching at a time when people are getting more comfortable with the idea of non-physical ways of purchasing goods and services. Offering itself as the platform for that marketplace to flourish and grow – particularly if it can do so with a better payment mechanism than currently on offer – could unlock tremendous value for Careem from its existing digital assets.

In the Pakistani context, this could be the equivalent of Apple’s use of the iTunes store to become the base for the iOS App Store on iPhones: an existing digital payment relationship successfully extended to a bigger marketplace.

“The super app will solidify Careem as a brand that aims to ‘make people’s lives easier’ and it will be above and beyond ride hailing,” said Baig. “Every new app installed in Pakistan is deleted within the first seven days, but the retention rate of customers on super apps is stronger. We have evidence from similar models in South East Asia and China, even though in China there is a part to be played by government support. But even without that government support, these apps succeed.”

While the optimism about Careem’s super app may be somewhat warranted, there is reason to be cautious: digital payments in Pakistan are not yet as ubiquitous as they would need to be in order for these apps to succeed. Indeed, even on Careem, cash payments remain not just an option, but one of the most frequently used methods of payment.

For the super app to work, Careem will need its digital wallet – Careem Pay – to succeed. On that front, there remain some regulatory hurdles that are still standing in the way.

“We are in talks with the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) for a license to completely turn Careem Pay into a digital wallet, and we have already gotten these licenses in Jordan and Saudi Arabia,” said Baig. “But in Pakistan, so far we only have closed-loop offerings for now.”

Closed loop offerings mean that Careem can accept money into its digital wallet and only allow people to send money to other users within its app, or other vendors who have signed on to use the app.

“We have opened ‘Daily Wallet’ for captains. Previously captains used to refuse rides on credit because of complaints that they get paid later. Now with this daily wallet they can withdraw their earnings on a daily basis,” said Baig.

“For customers we have recharge and mobile top-ups, and peer to peer transfers. They can also make donations through our app, and with Super App we aim to have utility bills payment on board very soon too. And eventually we may also offer Careem cards as well.”

–Additional reporting by Syeda Masooma

Hello sir I am Asad Ali from Lahore sar main aap ki company mein kam karta hun careem captain sar main aapki kya company mein do sal kam Kiya hai jismein mujhe kafi achcha laga acchi aamdani thi the lekin waqt ke sath aapki policy change ho gai chin policy mein captain account block hue jismein aapane bonus bhi khatm kar diya bare dukh se kahana paraha hai jiski vajah se kafi captain berozgar hue lihaza main aapse Durga khast karta hun ke hamara bonus on kiya jaaye a car ka aapka 25% bhi hamen dena padta hai uske alava government tax bhi hamen dena padta hai FIR fuel bhi hi FIR car ki maintenance bhi hai main aapse fast karta hun is bare mein aap kuchh Karen captain ke liye mujhe ummid hai hai aap jald is bare mein jawab denge aur captain ke liye ye koi acchi policy laenge thanks khuda Hafiz