If you grew up in a middle class household anywhere in South Asia, the odds are high that your grandmother owned a Singer sewing machine. You may even have had a Singer water heater in your home. Singer, the company that started off manufacturing sewing machines in Boston in 1850, has had a presence in the subcontinent since 1877.

When it comes to household brand names, Singer is as old as they come in this part of the world.

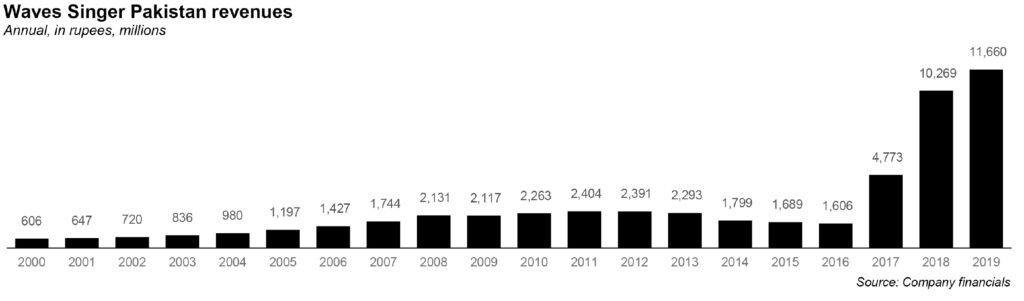

And then there is Waves, a new brand, but nonetheless one that has managed to make its way into the minds of many households, if not necessarily actually in those homes. The white goods company was established in 1971 by a Lahori family, and began to produce refrigerators in 1976. It began to make air conditioners in 2002, microwaves in 2003, and washing machines in 2004. It was then bought out by Singer Pakistan Ltd (the sewing machine company), in 2017.

The combined company owns brands and manufactures products that have a major presence in most middle class households in the country, an enviable platform upon which to build its growth story.

So why is one of Pakistan’s iconic refrigerator and freezer companies deciding to pivot, and enter the real estate market? On August 11, the company announced that it would be entering the business of developing affordable housing units and other related real estate activities. And on August 13, the company said that the new real estate venture would be part of the principal lines of business for Waves Singer, subject to the approval of shareholders and the Securities and Exchanges Commission of Pakistan (SECP).

Why would Waves consider this? The company’s current business is doing rather well. It has a significant presence in the country, with 2,398 dealers, warehouses, and service centers across Pakistan. Sure, it has a measly 5% share of refrigerators in Pakistan, compared to Dawlances’s 27% share, or Pak Electron’s (PEL) 25% share. But it has still made positive net income for the last four years straight, earning Rs382 million in 2018, and Rs378 million in 2019.

There are two ways to look at this decision.

The first is the obvious one. Ever since the federal government announced an incentive package for the real estate and construction industry in April 2020, it has become incredibly lucrative to enter the real estate market, especially the affordable housing segment.

The scheme is considered somewhat controversial, since investors no longer have to declare the source of income for their investments until the end of the year. But investors will also be granted a waiver of up to 90% on tax, if they are investing in construction projects under the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme. The industry will also have a fixed tax regime – more akin to a sales tax – instead of taxes on profits. The government even allocated Rs30 billion for the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme in the new budget for fiscal year 2021.

Additionally, the central bank has asked commercial banks to allocate 5% of their total lending to the construction sector. This will hopefully improve lending in general: as is, banks’ current exposure to the sector is only at 1% of overall loans.

So far, so good. One can see why Waves, or any entity, might be interested in this sphere. But there is another interesting reason, one not so readily apparent, and for that, you have to look at a sugar mill in Faisalabad. It has to do with how businesses think about the best use of their assets and capabilities.

The Crescent Sugar Mills and Distillery was not just Faisalabad’s oldest sugar mill, but also probably one of Pakistan’s, as it was first incorporated in 1959, and listed on the exchange in 1965. Yet, in 2010 the board made the decision to sell the sugar mill. In 2012, the company’s name was changed from ‘Crescent Sugar Mills & Distillery Limited’, to ‘Crescent Cotton Mills Limited’, to reflect the company’s new found interest in cotton yarn.

The sugar mill was sold off not because the sugar industry was not lucrative: it was that something else was just making more money. And in this case, it was the land the sugar mill was sitting on. The factory was located at a 100-acre complex in Nishatabad. This neighbourhood of Faisalabad used to be on the outskirts in the 1960s, when the factory was first set up. However, as the city of Faisalabad grew and became richer, Nishatabad became an upper middle class neighbourhood.

And what do upper middle class neighbourhoods around the world have in common? Sky-rocketing real estate value. Eventually, the owners of Crescent Sugar Mill realized that they would actually make more money just from the land itself, rather than go through the hassle of operating a whole factory, and then trying to sell sugar.

So on this prime real estate, located just 10 minutes away from the city’s center, the company in 2012 decided to bulldoze the factory and create a residential colony. It is another matter, that the company is still waiting for government approvals to convert this industrial land into residential real-estate.

There is a key difference from Waves (Crescent converted its existing asset into real estate, while Waves is just entering real estate) but the logic remains the same: why manufacture goods if the margins are low, when instead there is money to be made in an entirely unrelated sector? As mentioned before, Waves only has a 5% share of the refrigerator market. Does it make sense to spend a lot of money on increasing manufacturing of refrigerators, improving marketing, competing with top players, just to get a marginally bigger slice of the refrigerator pie; or to instead try your hand at real estate development, particularly when the government and central bank have incentivized you?

If Waves succeeds, it is slightly worrying. This magazine has previously explored what happens when Pakstani individuals overinvest in real estate: it stunts economic growth. But imagine that the resulting skyrocketing land prices, means that even companies decide that to get into the real estate market is worthwhile – industrial capabilities be damned. That is a truly bizarre landscape to consider.

Waves have merely 8 acre (64 kanal) land then how will they convert it into housing scheme? Second how do you see the potential of Waves Pakistan in FY21 and FY22.

Thank You