Six hours away from Manila, the bustling capital of the Philippines, a Pakistani from Azad Kashmir rules over an empire of garbage. Here, Azhar ‘Bill’ Khan, claims his international advisory firm has set-up the only waste-to-energy plant in the Philippines.

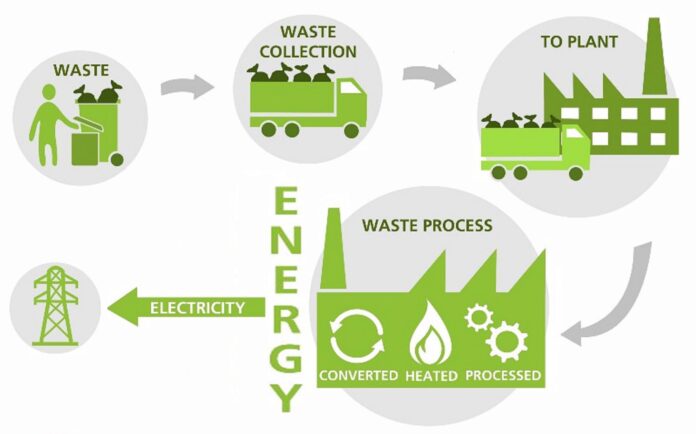

A waste-to-energy plant is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a waste management facility that burns wastes to produce electricity. For a country like the Philippines, where there is an acute energy shortage despite being a middle income country, the Waste-to-Energy (WtE) model is attractive. The archipelagic country with a population of 109 million and GDP of $376 billion (compared to Pakistan with 220 million people and GDP of $278.2 billion) produces 41,000 tonnes of garbage everyday, (Pakistan produces 71,000 tonnes).

WtE is attractive exactly because there is plenty of waste to go around, the government is always looking for ways to dispose of it, and as the Philippines continues on its path of accelerated economic growth, the demand for energy is increasing. The initial efforts made to bridge this gap have been through sustainable sources of energy, particularly renewable sources, that are rapidly growing in a number of projects and spreading across different regions in the country. At present, renewable energy accounts for 25% of the total energy generation mix and is expected to increase the capacity in the next few years by investing in localized resources.

But other than renewable energy, WtE has also become a promising avenue for energy production. And while the Zharbiz plant solves two problems, waste management and energy production, the project has lacked financing at a city level, and has also suffered from conflicts with the prevailing “Clean Air Act,” which prohibits incineration of municipal solid wastes – something central to the WtE model.

With its global outlook and international partner’s relationships, Zharbiz International Holdings says it specialises in government and private sector projects, along with operations in renewable energy, education, hospitality, innovative technology-based development, printing, commodity trading, and infrastructure, with business interests in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

But is the WtE model they are trying to sell in the Philippines outdated, and why does Azhar think Pakistan has something to gain from the model Zharbiz is employing overseas?

Garbage to energy

With more than 25 years of business experience, Azhar Khan has spent most of his life away from his home country. From working as an advisor to the President of Sierra Leone on energy, to consulting for different oil, gas, mining, computer, and waste management companies. He has also spent a lifetime in the Philippines. To hear him speak of it, WtE is not just a solution to a problem, it is the need of the hour.

“In Baguio city in Philippines, we have been putting up a WtE plant which requires anywhere from 4-5 hectares, based on gasification technology, eliminating garbage completely and creating energy out of it,” Azhar Khan tells us. “So the two issues being solved are eliminating waste and creating energy for shortages. We are processing around 500 metric tons of garbage presently and for Metro Manila, we are in talks to set up a plant that can process around 7,000 metric tonnes of waste.”

Zharbiz is solving a two fold problem, energy production and waste management. Naturally, both for Azhar Khan and for Profit, the mind goes immediately to Pakistan, another country that suffers chronically from both a lack of waste management solutions as well as an energy shortfall. And as with any starry eyed expat, solving the problems of the motherland is something Khan has been thinking about at some length for some time.

“In Pakistan, the garbage or the trash that we create, where does it go? Let’s say Karachi or Lahore or Islamabad, landfills where the waste is disposed can create deadly diseases with far reaching consequences,” he says. “This should scare us more now than ever with what we have seen Covid-19 doing. It is a real health issue. Plastic creates more environmental issues than any other form of garbage. Then everything is being dumped there so it makes issues worse,” says Azhar.

Of course, for all the talk of being environmentally friendly and protecting our ecosystem, there is the fact that one of the criticisms against WtE plants is that they are not environmentally friendly. These plants are expensive to set up, and when the garbage is collected in a disposal dump, it releases harmful fumes, mercury, dioxins, lead, and other pollutants. In terms of climate impact, when the incinerators burn, they emit more carbon dioxide per unit of electricity than coal-fired power plants.

However, Khan says that Zharbiz’s proposed WtE plant does not rely on landfills to convert garbage, and will instead have it delivered to them directly. “What we have done to solve this problem is a zero-landfill solution. The current practice is to burn the garbage in incinerators, creating more emissions and climate change problems. Then you have individuals who basically pick up plastic and sell it to others creating a market for resale of plastic instead of disposing of it. It creates a lot of issues, it is bad for the water and the air,” Azhar stresses.

The Pakistan equation

A zero landfill initiative has a single, finite goal: to divert 100 percent of industrial materials from local landfills. A zero landfill initiative may consider recycling a satisfactory solution for non- product outputs and stop there without exploring options that are higher on the waste solutions hierarchy. And how does he propose something like this play out in Pakistan? For Azhar Khan, the only answer is public-private partnership.

“I am acutely aware of the problems that one has to go through to tangibly realise the WtE project for Pakistan. Political engineering for one,” he says. “There needs to be a public-private partnership. Government departments from the energy and environment are involved which requires a lot of political engineering to complete the project. It requires expertise in engineering, technology, finances, and politics, which we have a good grip of here, where we are trying to specialise.”

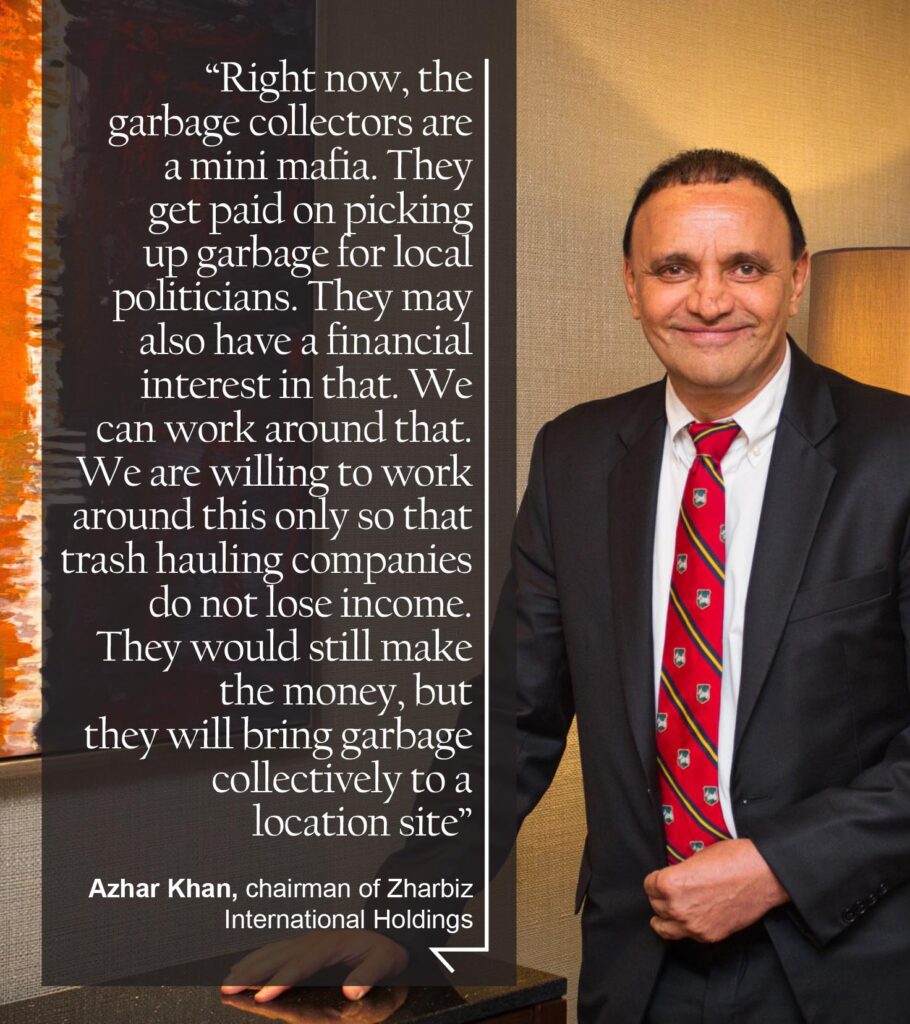

Whether Zharbiz’s business experience, being a company associated with the government in Philippines that has previously carried out vehicle inspection projects, will be translatable to Pakistan is not a given. The vested interests in Pakistan are totally different. However, Azhar claims that he can probably find a way around it with everyone comfortable with the project.

“The problem, at the end of the day, is waste. And if it is not managed properly, it will end up in places where it does not belong, for example, in the sea. Karachi’s beaches are not clean. It eventually becomes an issue for tourism as well,” he says. “Right now, the garbage collectors are a mini mafia. They get paid on picking up garbage for local politicians. They may also have a financial interest in that. We can work around that. We are willing to work around this only so that trash hauling companies do not lose income. They would still make the money, but they will bring garbage collectively to a location site.”

The plant’s feasibility as a business, because it is a for-profit project after all, also depends on the type of waste. Azhar says that plastic creates more energy, so the waste is also analysed, besides the location, the type of machinery for the actual type of waste from the area where it is created and, more importantly, the total waste production of that area where the plant is going to be located will all be contributing factors.

“You are looking at an over $50 million investment for a small plant, 500 tonnes. The big ones, from 5,000-7,000 tonnes, those would be the major projects of around $250 million,” Azhar said. The obvious question here is whether Zharbiz has the financial muscle to pull something like this off. The answer is that they do not, but with a consortium, they hope they can get things done.

“The financial muscle we can create with our consortium, but we would need the basics clarified how much waste is available in a certain area and then the guarantee of the waste, agreement with the trash hauling companies, that they will be providing that waste on a long-term basis because the plant life cycle is 25-40 years,” he explains. “The land required initially would be five hectares, and then we would have to see how far from the landfill is that plant. If the area is able to create 500 metric tonnes of waste, then it becomes workableOur funding will come from a consortium of investors from the private sector. The government would only be providing the land. It is going to be a public-private partnership project.”

The Drones

For now, Khan is dreaming big for sure. Coming into Pakistan as a business with money is hard enough, but coming in with middling financial muscle and expecting the government to be a fair and understanding partner in a public-private partnership is a hard sell. But if Zharbiz manages to achieve what they claim they can, they won’t just be bringing a WtE plant to Pakistan. No, their plans go beyond that. And they are very different from anything you would expect: passenger drones.

Within a few years, the automobile sector will be vastly different from what we see today. Autonomous cars are already hitting the roads, and while Pakistan is usually the last to catch up, the government’s Electric Vehicles policy gives hope for the future. More importantly, these changes will come with the birth of an entire new ecosystem of industries.

Preparing for this kind of future, Zharbiz feels that Pakistan will be an ideal market to introduce their passenger drones, with its Guangzhou, China-based partner EHang that specialises in autonomous drones.

But why would China, which is already making huge investments in Pakistan, choose to do so through Zharbiz? The answer lies in the fact that Zharbiz is introducing these drones in the Philippines for passenger travel and firefighting, and then plans to enter them in the Pakistani market, giving them the market edge of pioneering.

“How will drones change the future? Let’s say you are at the Lahore Airport, and you are trying to get to the main city or a hotel. There may be a lot of traffic, but we have the solution for you,” explains Khan. “We may have a small hangar, let’s say, at the airport, so people, from the high- income group, can be picked up and dropped off at Pearl Continental or Avari. The drone will be unmanned, operated through a command and control centre that will be established in the city. You just have to put in the address of the person to be picked up with their details, and then the drone takes off and picks up that person and drops him off at the location.”

Azhar believes that passenger drones will have many use cases, with greater implications for the future. It costs less than a helicopter, you do not need to spend money on the pilot, or having any fuel cost, and very expensive annual inspection costs.

“This one, we would be setting up for both the private sector and the public sector. They would be passenger taxis for people, and we could also introduce them privately for tourism. In the Philippines, for example, the fire chief plans to use it for firefighting instead of having firetrucks because of the traffic congestion that can multiply the damage many times over. The firefighting drone can be programmed to be in that location in five minutes. We are currently negotiating terms of reference with the government of Philippines,” explains Khan.

The company plans to establish manual control centres where the drones cover a 60-mile radius. And, as Azhar claims, it is cost-effective. For a two-passenger drone, a one-way trip might cost $100. That is not a small amount for a Pakistani commuter, but the service does not target the average commuter. “Yes, it is costly, but not for someone who’d be spending two hours on the road, stuck in a traffic jam, getting late to sign a lucrative business deal. That’s the sort of people we will market it to,” Azhar says.