The year 2020 has been a rough year, by all accounts. A global pandemic devastated entire societies and economies, and Pakistan was not spared. New phrases entered our lexicon: lockdown, community spread, viral load.

That is why when investment bank Arif Habib Limited releases a research report on Pakistan’s economy titled “Symptomatic! But likely to test negative”, no one bats an eye. Oh, of course, the economy is symptomatic. This year has prepped me for such inanities.

Wordplay aside, the report, prepared by analyst Sana Tawfik, is actually a good indicator of where the country might be headed. It is also a useful reminder of that somehow, amazingly, Pakistan always manages to scrape by. Despite worldwide lockdowns and the temporary halt of the IMF program, Pakistan managed to close the fiscal year 2020 with a 78% lower current account $3 billion, and an 88% jump in foreign direct investment (FDI).

“The global economy continues facing turmoil in 2020, but we remain largely optimistic in our outlook for Pakistan’s external account, given the continued attempts to find a resolution to dwindling trade position and continuous inflows of remittances,” noted Tawfik.

Tawfik’s report analysed a few key sectors: the current account, imports, exports, remittances, and reserves. We will take a look at each.

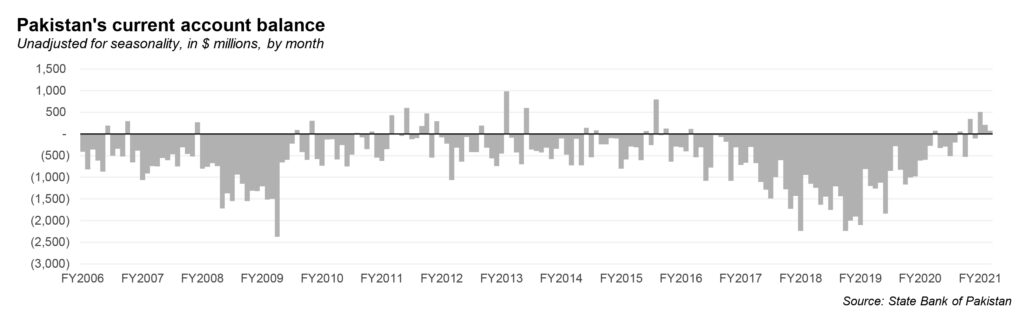

Current Account

First let us look at the facts: the first three months of fiscal year 2021 could not have gone better. Consider: in the first quarter of 2021, Pakistan had a current account surplus of $792 million. In the same period last year, that was a deficit of $1,492 million. To further highlight the jump: this quarterly surplus is the first in five years (with the last being in the third quarter of fiscal year 2015, at $514 million). This is also the highest surplus after the first quarter of fiscal year 2004 ($1.1 billion), or 17 years. Indeed, just in September alone, the balance stood at a respectable $73 million; it was a deficit of $278 million in September 2019.

So what happened? According to Tawfik, September saw a 31% year-on-year increase, or $544 million rise in remittances, along with a 5.4% year-on-year increase in total exports, mostly led by export of services, which jumped 30% month-on-month. This helped the current account balance, even though imports also increased by 11.6% year-on-year, or $452 million, in the same period.

Still, that lucky streak is not enough to overcome a sense of trepidation. “For the remaining period of the current fiscal year 2021, we are of the view that the trade balance is still on a shaky ground as global uncertainty escalates,” says Tawfik. That is why she thinks trade balance may swing into deficit in the second half of fiscal year 2021, with the current account posting a deficit of $2.5 billion, or 0.9% of the gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of 2021.

Why so bleak? Well import growth is still likely to outstrip export growth – despite the government following a policy of limiting the import of certain products, rationing imports and increasing reliance on local production. Ultimately, there might be a 2% jump in imports, or $52 billion in fiscal year 2021, while exports are to grow 3%, or $29 billion.

Imports

Tawfik somewhat drily notes that, that any so-called ‘growth’ phase of Pakistan, often means the external account will suffer. The country’s growth is really just import-led, as evidenced by the fact in the last five years, imports have contributed an average of 17% to the GDP, while exports have contributed just 8% during the said period.

And it is the same case this year. In September 2020, imports jumped by 18% month-on-month, to $4,358 million, compared to $3,696 million in August 2020. On a yearly basis, imports in September jumped 15%.

The Covid-19 pandemic initially meant that there was somewhat of decline in imports, due to dampened aggregate demand in the economy. That is how in the first quarter of the fiscal year 2021, total imports recorded a decline of 8% year-on-year to $12,374 million.

Still, this is expected to creep up as lockdowns have eased. Furthermore, the government is expected to start an ‘expansionary fiscal policy’, code for expect more imports. Tawfik expects goods’ imports in 2021 to expand 4% year-on-year $44 billion.

What do those imports consist of? Some are expected, such as the machinery imports increasing by 9% in 2021, as the cement and steel sectors are expected to kick off, especially considering the construction package announced by the government earlier this year. Transport imports will also growth of 22% this year.

Others are less expected. Far from exporting textile, Pakistan’s imports of textiles will jump by 26% year-on-year. The locust attacks, well documented in this magazine, and monsoon rains have severely affected the cotton crop in Pakistan this year. Locusts are also responsible for food imports to increase by 13% year-on-year; as is, Pakistan has begun to import essentials like wheat and sugar.

As for our weak spot, oil, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that we are currently experiencing lower crude oil prices, with fiscal year 2021’s prices at $45 a barrel, compared to the $54 a barrel in 2020 (one can thank the pandemic with the slump in oil demand). This should help Pakistan make a savings of around $2 billion.

However, the pandemic will end (it has to, one day). And with that, aggregate demand will creep up again, offsetting the impact of those savings. If oil imports made up 22%of the 2020 import bill, they will make up 19% of 2021’s bill.

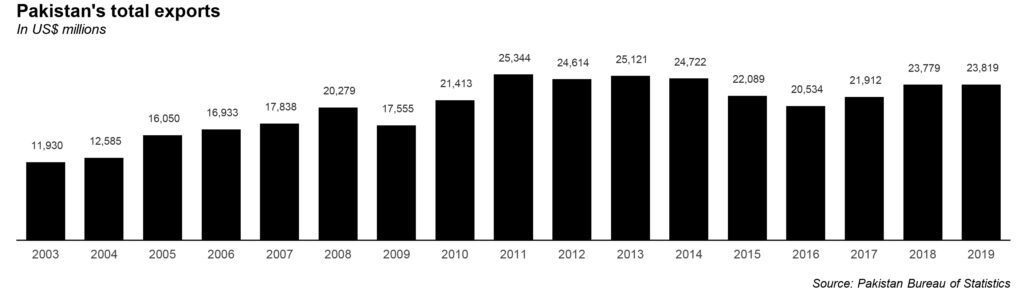

Exports

To our government’s credit, it is not like it was not aware of the precarious state of our exports, particularly because of the pandemic. The State Bank of Pakistan started a bunch of measures in March 2020, such as availing cheaper credit under the Export Financing Scheme, and more relaxed conditions for Long Term Financing Facility.

According to Tawfik, these measures bore fruit eventually. In September 2020, total exports increased by 29% month-on-month to $2,414 million, compared with $1,867 million recorded in the previous month. On a yearly basis, total exports increased by 5% in the same month. Specifically, the export of goods increased 4% year-on-year, while export of services jumped 30% year-on-year in September.

And that is how total exports during the first quarter of fiscal year 2021 stood at $6,583 million. This is 9% short of the figures in the same period last year, but Tawfi is nonetheless relieved. She notes: “Nonetheless, we have so far limited the long-term damage and facilitated the recovery, backed by SBP’s monetary stimuli and liquidity support. Going forward, we expect exports of goods to improve by 3% YoY to USD 23bn in FY21.”

According to Tawfik, that would depend on the world, and trading partners step up. Since the pandemic is still very much in its second phase around the world, she recommends Pakistani exporters on catering to demand for medical instruments, health clothing, pharmaceutical products, bed linen, towels, and simple garments and clothing. Similarly, Pakistani exporters could focus on food items, vegetables and fruits, due to rules relaxations.

What about Pakistan’s problem child, the textile sector? Though it accounts for 55% of our total exports, the sector relied too heavily on raw material, dyes, and chemicals from China – unfortunate, since the pandemic caused a slowdown in that country. Still, in the first quarter of 2021, textile exports rose 13% year-on-year, or $3.4 billion. While Tawfik dubbed this promising, she did not mince words regarding the litany of risks that still exist: supply constraints from the locust attacks, monsoon problems, costs of productions, fluctuation interest rates, or even energy tariff hikes.

Meanwhile, the rupee’s stability, or lack thereof, threatens to derail the textile sector. If it remains at Rs161 to a dollar by the end of the year 2020, then the sector can breathe easy. However, if it appreciates (which, let’s face it, it will) it could put pressure on textile exports.

Still, it is not all doom and gloom, “Our expectation is that the textile segment will post a 6% YoY higher export growth during FY21,” says Tawfik.

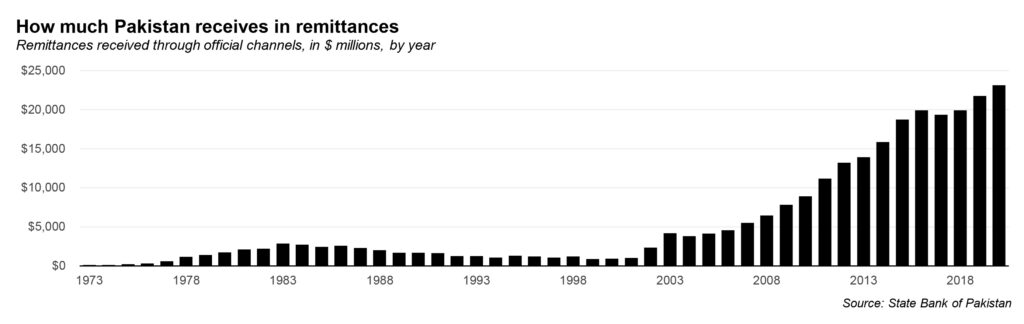

Remittances

If one goes by PTI’s enthusiastic tweets, it would seem expatriate Pakistanis had never sent money before the party was in power. The gleeful tweets aside, remittances have been rising (erratically, according to Tawfik) in the calendar year 2020. In fact, September was the fourth consecutive month Pakistan reported over $2 billion in remittance inflow, at $2,284 million, or a jump of 31% year-on-year compared to $1,740 million in September 2019. In total, in the first quarter of fiscal year 2021, remittances clocked in at $7,144 million, an increase of 31% year-on-year.

Most of the inflows were from the usual suspects: Saudi Arabia, UAE, United States, and the United Kingdom.

The inflows have been so consistent, that it has confounded many analysts. Several theories are put forward, including by Tawfik herself: the suspension of international travelling, and workers sending money to their families more than usual during the pandemic. There has also been a crackdown on unofficial channels such as “Hundi” and “Hawala”. Turns out less ‘suitcases full of money on planes’ and more ‘official bank accounts’ makes a difference to the country’s current account.

While Tawfik expects the norm of over $2 billion to continue till the end of the year, the fiscal year 2021 is another story altogether.

“As the year unfolds, we expect remittances flow to weaken with international economies returning to normalcy…In our opinion, the declining trend in remittances will have adverse repercussions on the economy, not to forget that our Current Account stability is heavily reliant on it,” notes Tawfik worryingly.

She explains that less remittances will mean the government will have to borrow more to keep reserves alive. On a micro level, less remittances means less income for families back home. A whole 4% of Pakistanis receive remittance income, according to the Asian Development Bank. And if Pakistanis don’t have enough money in their accounts, that will affect aggregate demand.

Still, history shows that Pakistan is well placed. Pakistan’s 10 year CAGR for remittances stands at 10.8%, higher than our neighbours Sri Lanka at 7.3%; Bangladesh, 5.4%; and India, 4.9%. Most of these counties have seen a rebound in remittances, and resilience to the global health crisis. Pakistan should be fine, too.

Reserves

Finally, our reserves. Pakistan’s international forex reserves rose to $19.4 billion in October 2020, up from $17.9 billion at the end of December 2019. Pakistan is just struggling to meet the minimum three month threshold for reserves (we are stuck at 2.9 months). On the bright side, Pakistan has generally had a higher average import cover than our neighbours between 2011 and 2019 (we have also had other problems in that period, so it’s not exactly a win).

The net foreign assets (NFA) of the banking system witnessed an inflow of Rs992 billion during fiscal year 2020. Then, in the first quarter of fiscal year 2021, an increase of Rs248 billion in the NFA in the country’s banking system was also added in our reserves, buoyed by a current account account surplus and the deferment of some repayments of foreign loans.

Still, in fiscal year 2021, Pakistan will have to pay up $10.3 billion, meaning the pressure is on. According to Economic Affairs Division’s September bulletin, Pakistan received $2.7 billion in the second month of fiscal year 2021: around $1.3 billion, as budgetary support assistance to restructure the economy; $149 million to repay maturing Sukuk and foreign commercial loans; $317 million as assistance for development of the economy, and $1 billion as safe deposits.

Around $798 million has already been repaid in the first two months of fiscal year 2021, and the remaining amount, that is $9.5 billion will have to be paid in the next 10 months. That is mildly alarming.