On the surface, what is something interesting that can be said about Habib Bank? Even the bank’s own corporate briefing presentation on November 20 seemed like a glowing tribute (for entirely good reasons). Yes, HBL is the country’s largest bank, not just by assets (Rs3.6 trillion), but also by lending (Rs1.1 trillion), deposits (Rs 2.7 trillion), customer base (30 million), bank branches (1,709) and small and medium size enterprises finance (Rs50 billion). It was a critical partner to the government in the Ehsaas program, and is even on track to become a ‘green’ finance institution. A bank in Pakistan that can afford to be worried about its carbon footprint is clearly a bank that has other departments under control.

Still, there are some interesting numbers that pop out. Take a look at the bank’s business lines. The bank had significant jumps in key areas: trade volumes shot up, with market share increasing from 9.4% to 10.8% this year, and home remittances had an especially good run, increasing by 29% to a market share of 8.2%. Indeed, the bank has its eyes set on remittances share to increase to double digits in 2021.

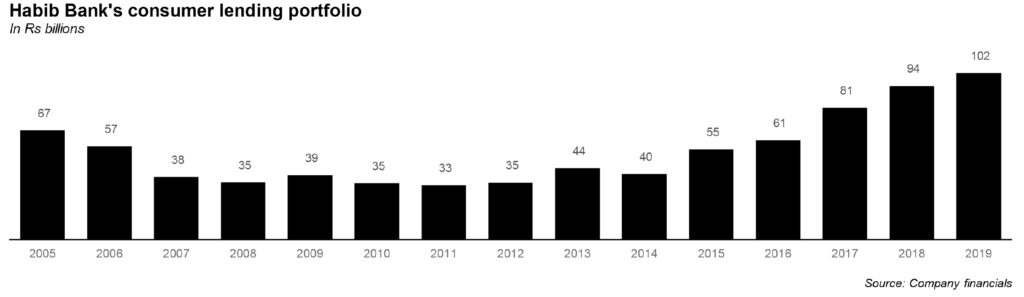

But none are as interesting as this: that the bank’s consumer lending shot up 19% year-to-date, from Rs60.7 billion in December 2019 to Rs71.9 billion in September 2020. This is noteworthy: HBL is already quite a large bank, with a sizable consumer lending portfolio, so this is potentially quite a big shift. It is also unusual: the globe, and this country has just suffered a pandemic that has collapsed economies and devastated the finances of households. Which begs the question: who is HBL lending to anyway?

It turns out that the answer actually lies in the pandemic. Let us explain.

First, it is not true that the pandemic did not affect HBL. As Syed Fawad Basir, analyst at Topline Securities, noted in his report sent to clients on November 26, under the State Bank of Pakistan’s relief scheme, the bank had to defer Rs90 billion worth of loans, while Rs23 billion was restructured. This is a full 13% of total loans that ended up having to be deferred.

Additionally, the bank’s loan book actually declined by 2% year-to-date due to lower commodity financing and corporate lending (to recall, 45% of the bank’s net loans of Rs1.1 trillion are to corporate business). HBL’s management believes there may be growth in the fourth quarter of 2020, which could potentially help the bank close the year on the same level as last year – though that remains to be seen.

Still, according to Basir, the bank’s management expects single digit growth in loan book in 2021 as industries will recover following the coronavirus pandemic (this is based on an HBL survey of around 350 its clients, where 80% said that production and sales levels would be back to pre-Covid levels by the end of this year).

And yet, though the overall loan book declined, auto financing actually increased from Rs17.1 billion in December 2019, to Rs24 billion in September 2020. This is what propelled the jump in consumer lending and also caused HBL’s market share in the auto loans corner to jump from fourth largest to second largest.

This actually solves the mystery of who HBL was lending to. According to Faizan Kamran, research analyst at Arif Habib Ltd., there was broad V-shaped recovery in 2020, following the massive cuts in the interest rates.

In the space between March 17 and June 25, the State Bank of Pakistan cut the policy rate by a whopping 625 basis points, from the relatively high 13.25% to 7%, which it has maintained since then. This recovery happened across certain sectors more affected by a cut in the interest rate, such steel, cement, and yes, car loans.

It is a view supported by Asad Ali, senior research analyst at KASB Securities, in a detailed report on automobiles sent to clients on November 30.

In it, he describes the inverse relation between lower interest rates and increase in demand for cars. The price of a new car in Pakistan starts from $7,000, which is nearly 5.7 times that of the Pakistani GDP per capita.

“Historically, any expansion in income combined with low interest rates has resulted in a surge in demand for automobiles,” says Ali. Car loans started increasing from 2013 onwards, as the unemployment rate fell from 6.3% to under 6%, and interest rates were at 6%. Indeed, automobile sales had a three-year compound annualised growth rate (CAGR) of 14% between 2013 and 2016, while the auto sector loan book increased at an astonishing three year CAGR of 27% in the same period.

The same trend is now repeating itself, after a drastic 635 basis point cut. In the last four months, auto loans have seen a stark rise of Rs29 billion. “We believe the low interest rate environment is likely to accelerate car purchases on loans as a function of lucrative vehicle affordability and revival in economic activity to improve incomes,” says Ali.

And that can only be good news for banks like HBL. Banks make money on their net interest margin, which is the difference between the interest rate they can charge borrowers and the rate they pay out to depositors. And the net interest margins for consumer lending tend to be significantly higher than for most other types of lending.

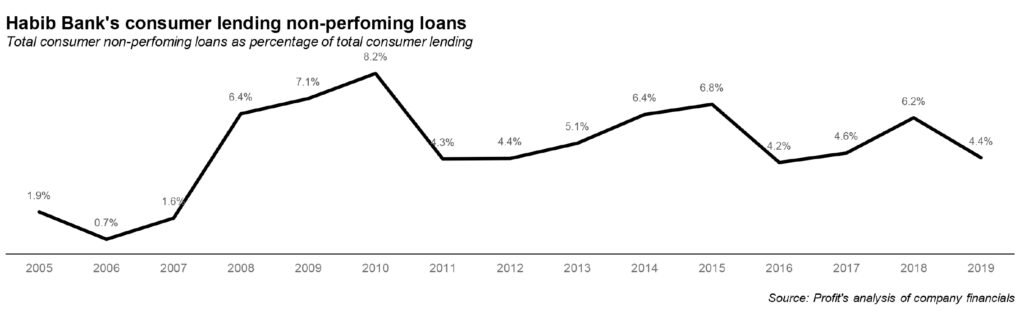

However, banks in Pakistan have been shy about expanding their consumer lending books since 2008, in large part because the financial crisis exposed just how fragile and unsophisticated the consumer lending divisions were at most banks. Prior to 2008, consumer lending typically accounted for a large chunk of most banks’ lending portfolios, with the industry average exposure to consumer lending going up to one-sixth of total lending prior to the crisis.

Post-2008, when the economic slowdown caused a massive spike in defaults on those consumer loans, banks became far more reluctant to give out such loans, despite the significantly higher net interest margins on consumer lending. The reason for this: the expected losses from bad loans more than wiped out the potential gains from higher net interest margins.

At Habib Bank, the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio – the proportion of loans that have defaulted as a percentage of the total amount of loans given out – for its consumer lending division spiked from a low of just 0.6% in 2006 to 8.2% in 2010, a sharp increase that meant booking losses on its balance sheet which carried through to its income statement. And Habib Bank’s experience was milder than that of most other banks, which saw even sharper increases in default rates.

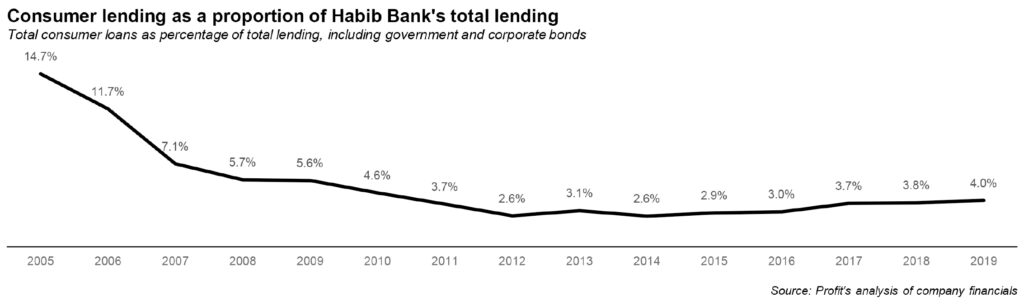

As a result, consumer lending now accounts for less than 5% of total lending at most banks, and at Habib Bank, it is only about 4% of total lending as of the end of 2019, the most recent period for which data is available. In 2005, consumer lending accounted for nearly 15% of total lending at Habib Bank. Profit defines a bank’s total lending as including its investments in government and corporate bonds, a definition that is wider than the ‘total advances’ definition preferred by most market analysts.

That 4% in lending represents an uptick from its trough of 2.6% of total lending, which the bank saw in 2012, when it was still cleaning up the aftermath of the financial crisis. And the most recent growth suggests that Habib Bank may have finally discovered a better way of ensuring that it can grow what could potentially become one of its most profitable business lines, given the fact that it has been able to take down its NPL ratio for consumer lending to below 5% in 2019.

Year wise thorough comparison would be helpful for general public to analyze the actual situation. Lot of jumps from one to other decades…..

just one question, if the auto financing was increasing, that should translate into increase in car sales, how come our car sales were decreasing as number of plants were closed due to lockdown yet in the same period HBL lent the money for people to buy cars?