What’s in a name? One sugar mill in Punjab has tried them all, but nothing seems to have stuck just yet.

In May 2007, a sugar mill was set up by the Colony Textile Mills. Colony owned 46.98% of the company in 2009 (the earliest available financial statement), while the CEO of Colony Textile Mills himself, Fareed Sheikh, owned 20.7% of the mill. While the office was based in Lahore, the two manufacturing facilities were located at Tehsil Phalia, District Mandi Bahauddin, and Tehsil Mian Channu, District Khanewal.

Colony Sugar Mills continued to be known as such, all the way until May 2015, when it was rebranded as Imperial Sugar. The mill not only distanced itself from the Colony logo and brand name, but got a brand new logo: gold swirly lettering, and a purple and gold crown to go with the name as well. (It did not, however, distance itself from Colony Textile Mills, which in 2015 still owned 16%, while three Sheikh relatives held 28%).

This name would then last another five years, before switching to Imperial Limited in August 2020. This time, the logo is an intricately designed I and L next to each other (no crown in sight). The change is recent enough that the link to Imperial Limited’s website still leads one to Imperial Sugar’s previously designed website. One can also still find Imperial Sugar in PSX’s listings.

The change of name last year was a deliberate move: the latest incarnation of the sugar mill is determined to not exist as a sugar mill at all. In a notice issued to the Pakistan Stock Exchange on January 4, 2021, the company said that the board of directors had discussed to consider and approve selling the land, building, plant and machinery at Tehsil Phalia, District Mandi Bahauddin (this is subject to the approval of shareholders in the forthcoming annual general meeting). That plant has a sugar plant that can refine 7,500 million tons a day, and an ethanol distillery with a production capacity of 135,000 million tons a day.

Except, of course, the mill has not really made any sugar for a while now. Profit took a look at the company’s financials to try and piece together what happened.

Perhaps the signs were always there. In the company’s earliest financial statement from 2009, the company had noted worryingly, that despite a higher revenue and higher profits that year, “Sugar and ethanol are both projected to be in short supply for the year 2009–2010, globally. Growers are claiming much higher prices ….In light of the prevailing situation, the company is also procuring sugarcane at higher rates. This will result in significant increase in the cost of production. Unless there is a corresponding increase in the sugar selling price, the profitability of the sugar divisions may be affected.”

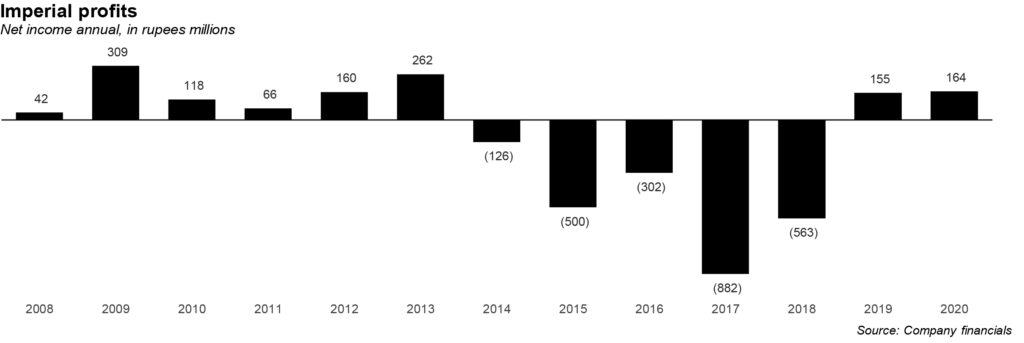

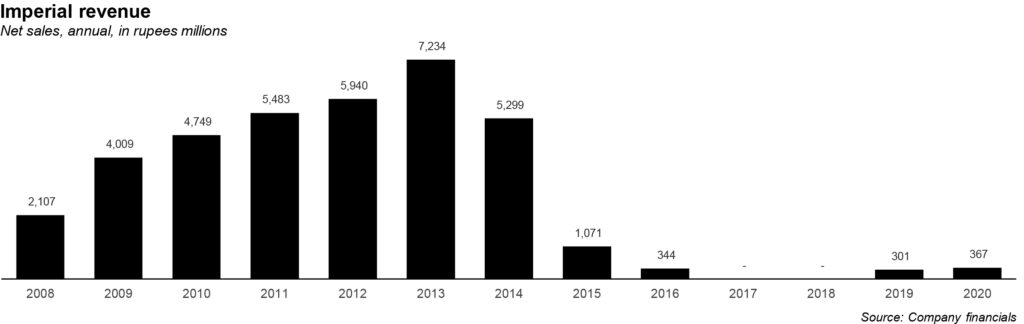

And that is exactly what happened. Between 2008 and 2013, objectively, the sugar mills revenues climbed, from Rs2,107 million to Rs7,234 million. And yet net income peaked in 2009 at Rs309 million, dropping to below Rs200 million between 2010 and 2012, and hitting Rs262 million in 2013.

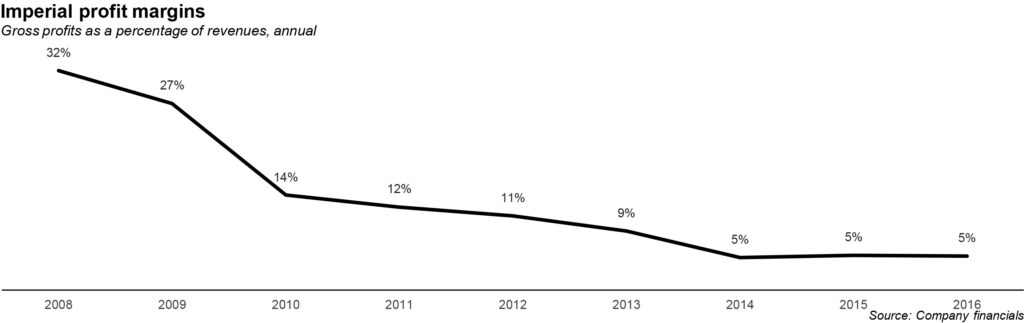

What explains this irregularity? One can look at the company’s gross margins during the same time period. In this case, the gross margin in 2008 stood at 32% – yet by 2013, that figure stood at 9%. In other words, in 2008, Imperial earned Rs32 in gross profit when compared to their costs of goods sold, but it earned Rs7 in gross profit by 2013. If a company’s ratio is falling (which it is, in this case), it means the sugar mill sold its inventory for a lower profit ie. it has to pay the farmers more for their sugar cane. That is exactly what Imperial predicted would happen, driving up costs of production and hurting the company.

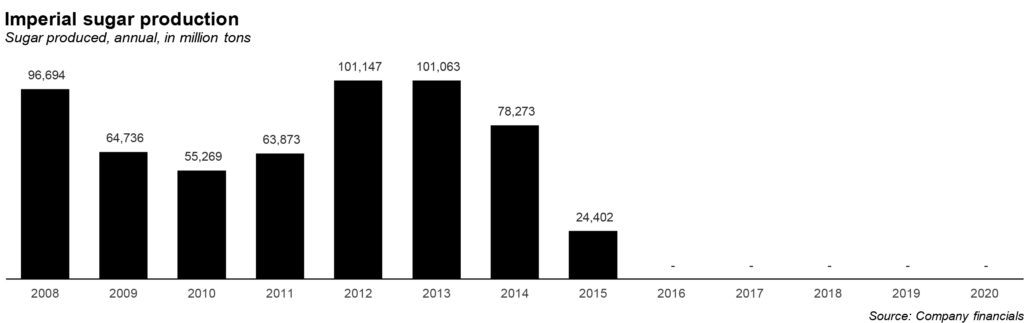

In 2014, the company made a loss for the first time, of Rs126 million, and the gross margins dipped again to just 5%. But things were only about to get worse. In 2015, the company made a loss of Rs500 million. The Phalia facility was temporarily shut down, while only intermittent crushing was going on at the Mian Chanu facility – both due to a lack of working capital.

It was to be the last year that the mill produced any sugar. In 2016, both units remained suspended, and the company took the decision to dispose of the plant’s properties and assets. It managed to execute at least half of that decision the next year, selling the Mian Chanu unit for Rs5,000 million in 2017. The proceeds from that sale were used to pay off loans from the National Bank of Pakistan, The Bank of Punjab, Habib Metropolitan Bank Limited and BankIslami Pakistan.

But the Phalia unit remains, as there seems to have been no agreement in the last four years. According to the company, the total current market value of the land, building, and plant, comes out to Rs8,765 million. In the meantime, the company has transformed into its current phase: “to carry on the business of buying, selling, holding or otherwise acquiring or investing the capital of the company in any sort of financial instruments.” In its recent annual report, it had only one line about potential future plans: to set up a hydroponics project. One wonders what the name of that project might be.

“….and an ethanol distillery with a production capacity of 135,000 million tons a day. ”

Whoops… the proof reading wasnt good enough…

Comments are closed.