Startups all have their quirks. It is either because they are trying to disrupt something, trying to draw attention to themselves or just trying to be a different kind of presence in their industry. Sometimes however, these quirks sound a little bizarre at first glance. Take Ricult for example. It is an agritech fintech company that has its major operations in Thailand and Pakistan and is headquartered in the United States.

While that is the best way to describe what Ricult does, it is an explanation-and-a-half and there is a lot to unpack here. Being an agritech company, of course, means that the startup focuses on using technology in agriculture to maximize yields and efficiency. Since it focuses on the financial services side of the agriculture business, it also falls into the category of being a financial technology or ‘fintech’ company.

That in itself is a mouthful, but add to that where it operates and even more eyebrows are raised. With its major operations in Thailand (middle-income) and Pakistan (lower-middle income), Ricult is headquartered in the high-income United States, and thus surfs a strange web.

The strangeness of the entire venture and how it is organised, however, makes more sense when you look at its origins. You see, it all happened at an entrepreneurship class at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where the Pakistani American Usman Javed first met the Thai-American Aukrit Unahalekhaka. The two quickly became friends, and discovered they had very similar ideas and inspiration.

While both were American raised, the idea of giving agriculture a technological boost came naturally. Pakistan is an agrarian economy, and Thailand is among the largest exporters of rice in the world. And while Thailand is considerably more developed and modern than Pakistan, it also has many of the same agricultural problems as here.

The solutions for both countries would then be similar. And since the two met at MIT, the world’s leading university in technology, that is where Ricult was incubated. Even today its headquarters are a couple of blocks away from the MIT campus, where Ricult continues to collaborate closely with MIT and relies heavily on data sciences and employs experts in data sciences that are all also based in the US.

Together, the two want to end the exploitative relationship that farmers have with middlemen predominantly, helping increase yields and incomes of small farmers in their respective home countries by entrenching technology into the agricultural ecosystem. Usman Javed currently operates as the CEO of Ricult Pakistan, and Aukrit Unahelekaka, who comes from a family of generational farmers in Thailand, is his Thai counterpart. With their headquarters in the US, the two hope it will be easier to attract institutional investors. This is their story.

Predicting the future of agriculture

Here is what the life of a small scale farmer looks like in Pakistan. In all likelihood, he does not own his own land and is a tenant farmer. This means that every year he has to pay rent to the owner of the land, no matter what the crop that year has been like. This means that the farmer sustains himself on the little that he can save for himself after the crops have been sold to pay off the rent. Since the owner has no responsibility or interest, the thought of using technology or modern techniques is a distant one.

In case you are a small scale farmer lucky enough to own your own piece of land, you suffer from the informality of the sector in Pakistan. Local middlemen remain important players in the entire agricultural value-chain that offers arbitrary prices to farmers for their produce. The middleman sells cheap and low quality farming inputs to the smallholder farmer on credit at exorbitant rates.

On this lent amount, he charges an annual markup of 60 per cent to 150 per cent, a variance which is subject to his generosity. But it doesn’t stop here. Come harvest time and the creditor takes all the produce from the farmer at a lower rate than the market rate, sells it to the market at the market rate, and then deducts the amount owed to him by the farmer to return the remaining amount to him. In most cases, the middleman refuses to release the full amount he owes to the farmer, thereby exploiting the farmer even further.

And what recourse does the middleman adopt when a natural disaster like floods hit the crop? Lend some more to the farmer and make him pay the outstanding amount next year. Always keeping him dependent and entrapped in the never-ending cycle of falling profit margins and rising debt. It is a vicious and never ending cycle.

The dependence on these middlemen and their exploitative practices is exactly what Ricult wants to put an end to. The company was the subject of a Profit profile back in 2017. The way they operate is to connect farmers with relevant stakeholders to buy inputs for crops, like fertilizers, and subsequently connected farmers with potential buyers of their crops.

The startup has since broadened its product offerings for farmers, like connecting farmers with banks to apply for loans, AI-based services that help farmers predict weather patterns and monitor crop health. Essentially, earlier Ricult was cutting out the middlemen that exploit farmers.

Now, they are doing that as well as acting as the middlemen between farmers and the banks.

Let us look at an example of how this works. If you are a farmer growing sugarcane in Pakistan, Ricult will be your partner throughout the lifecycle of the crop. From pre-sowing until the selling of the crop, the platform enables farmers to make insightful decisions about the farm and the crops through remote sensing that it uses to monitor the farms. This helps farmers take the right decisions in terms of what kinds of inputs to apply, at what time they should be applied, all to improve the yield of the crop.

Now, there is also the additional benefit of having access to loans and financing. Usually, a farmer can simply use Ricult to see what inputs they should be using and when. This is important because it gives small scale farmers access to modern farming techniques that only large scale farmers in Pakistan are currently using.

But sometimes these inputs can be expensive, or the weather can cause problems. In such a situation, these farmers can connect with banks and apply for loans through the Ricult application. Finally, the application connects farmers with mills or middlemen to sell the crop to, giving them the best rates in the process, also eliminating delays in the transaction.

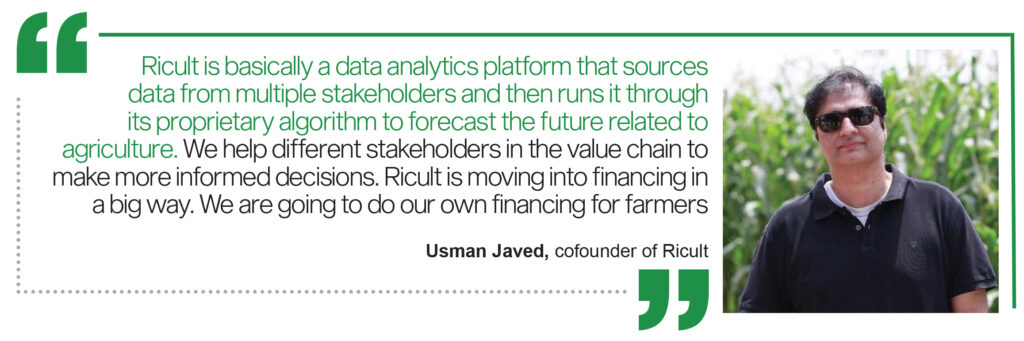

“Ricult is basically a data analytics platform that sources data from multiple stakeholders and then runs it through its proprietary algorithm to forecast the future related to agriculture,” explains Usman. “We help different stakeholders in the value chain to make more informed decisions. Ricult is moving into financing in a big way. We are going to do our own financing for farmers.”

“We are working on introducing a model where we will pay off the farmer at the time of his harvest. He would not need to find buyers and wait for payments that would eventually hurt his cash flows. This model will be a three way arrangement between Ricult, farmer and a mill where the farmer will have an option that if any mill accepts his product and he wants money instantly, he can take the money from us and we will recover the payment from the mill,” Usman, who also heads agritech initiative at National Incubation Centre Lahore (NICL), explains.

Agriculture is among the five key initiatives launched at NICL, as part of its broader strategy to overhaul the technology incubation centre, to promote entrepreneurship in education, environment, healthcare and financial inclusion, besides agriculture.

“Unfortunately, in Pakistan, nobody really focuses on output financing even though it is a concept that is practically implemented in all parts of the world,” Usman adds. Ricult is doing all that it is doing, and more that is in the pipeline, on the back of $5 million that it raised from institutional investors in the US, Singapore and Thailand between 2017 and today.

Ricult Pakistan vs Ricult Thailand

It has been a strong-growth journey for Ricult so far. The startup has signed up farmers that now run in hundreds of thousands in numbers that use the Ricult application. The startup has witnessed more growth over the years in Thailand as compared to Pakistan.

Thailand’s GDP in 2019 was $543 billion whereas Pakistan’s GDP for the same year was $278 billion, which is almost half of what Thailand’s gross domestic product was in 2019. This is despite the fact that Pakistan spans over a much larger area, 881,913 km², against Thailand that spans over an area of 513,120 km². The Southeast Asian country is among the biggest rice exporters in the world. It has a 16.2 million labor force that works in agriculture. In contrast, almost 40 million people are farmers in Pakistan, of which, 60 per cent or 24 million are smallholder farmers, according to the latest census.

But with the adult literacy rate above 90% against Pakistan’s 59%, the Thai farmers are generally considered very progressive and have been able to stay ahead of Pakistani farmers when it comes to adopting technology. Hence the better performance of Ricult Thailand despite the fact that Pakistani agriculture is bigger than agriculture in Thailand.

The Thai government takes digitisation and technology in agriculture very seriously as well. “The Central Bank of Thailand invited us over to understand what we were planning to do in agriculture. They were actually keen to learn themselves about the technologies that we were using and how it all worked,” says Usman Javaid.

The general opinion about Pakistan is that it is a nation with people that are resistant to change. Startups have complained about how technology adoption has become a challenge for their growth in rural Pakistan because people sometimes don’t understand or don’t want to understand how technology can improve their lives.

Sometimes, however, this is little more than an excuse people use when they fail to capture the imagination of these farmers living in rural areas. Go to a village in South Punjab and they will tell you about their newfound love and fascination for TikTok and Facebook. They know and love these platforms because they are intuitive to use, and these people are intelligent and interested in what the world has to offer.

However, they will not know about agritech and fintech applications because they have perhaps been badly marketed to them and they do not trust lofty promises. It is also because applications like TikTok and Facebook have proliferated in the rural expanses in Pakistan, Ricult markets its platform through these applications besides through field agents and training programmes.

The proliferation of the internet out of urban centers means that a technological revolution is possible, but it will not happen if the people leading it turn up their noses and say it is the fault of the farmers that they are not coming to their platforms. The platforms must be taken to the farmers. The expectation that somehow these companies are doing a favour to the farmers is painfully banal. The farmers are the customers in this case, and they must be wooed, not scoffed at.

The general lack of interest and knowledge about apps like Ricult is why Ricult Thailand has been able to stay ahead of Ricult Pakistan. It is true that farmers in Thailand might be more aware of these possibilities, but that is because the scale of the issue is different in both companies, and that is something Ricult Pakistan must understand and work accordingly with.

In numbers, the startup’s Thailand operations boast 180,000 registered farmers using the Ricult application whereas in Pakistan, the number stands at 120,000 farmers on the application. The overall numbers are higher and in Thailand presently even though Ricult Thailand started operations in 2017 whereas Ricult Pakistan started operations a year earlier.

“The farmers in Thailand is progressive. The cell phone penetration is also slightly better in Thailand and that reflects in our numbers,” says Usman. “Where we add a thousand farmers on our platform every week in Pakistan, in Thailand, we add a thousand farmers every day. We started from tehsil (sub-district) Kasur and farmers on our application are not concentrated in Kasur only. We have expanded towards at least 17 tehsils in Punjab now where farmers use our application,” he adds.

While the company has expanded its geographical footprint and moved beyond Kasur, it has not yet gone beyond Punjab into other provinces. And it has not gone beyond the usual cash crops that its AI system can monitor even in Punjab. “These are small crops that we want to introduce on our platform that can be monitored for a farmer. We are looking at chillies, soybean; crops that are majorly imported into Pakistan,” says Usman.

Now how does Ricult make money? It does not charge the farmers anything. It charges the institutions that it works with. Banks for instance. Whenever a farmer applies for a loan at a bank using the Ricult mobile app, Ricult makes money out of that by charging the bank.

Revenues at the company have also swelled since 2017. The CEO, Usman, says that the year-on-year growth in revenue has remained between 40-50% and expects a further increase as new services like financing for farmers are rolled out. “By 2021, as new interfaces are launched on the Ricult app, we aim to hit 1 million number of farmers using the Ricult platform in both Thailand and Pakistan,” Usman says.