You do not have to be young to grow a business, but you do have to be hungry. But founders of a company – after a long run of success – can find themselves in a position where they are no longer as driven as they once were, but competing against those who are.

That, it seems, is the position Shan Foods finds itself in. Its founder and chairman – Sikandar Sultan – has an extraordinary story of building a business – and a brand that is now a household name in several countries around the world – almost completely from scratch alongside his wife over the past 40 years. (Citing privacy concerns, Sikandar’s wife, through him, declined to be identified by name.)

Now, however, comes the moment of truth: Sikandar knows he needs to do the hand off to a new generation of management, and is currently orchestrating the transition, but faces a challenging competitive environment.

It comes down to this: Shan’s biggest competitor is larger by overall revenue, has a broader product portfolio, and is growing faster. All of this is happening while the company is still in the midst of deciding its future direction, one of the central questions of which – until recently – was whether or not to go public through a listing on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Shan Foods’ management has publicly stated in the past that they were considering an initial public offering (IPO), though in a recent interview with Profit, the company’s chairman made it clear that an IPO was no longer on the cards. As we will demonstrate through the analysis presented in this story, however, it is our contention that – far from ruling it out – Shan Foods should actively pursue a public listing. Because one of the biggest advantages their competitor National Foods has over them, in our opinion, is that it is a publicly listed company.

How Shan got its start

Before diving into that analysis, however, we would like to lay out how Shan became such an iconic brand, from its humble origins to its current heyday.

The story starts with Sikandar, who comes from a family that had historically been in completely different business lines. His grandfather made carriages, some of which the family claims were even used in the ceremony for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation ceremony in 1953. And his father was in the carpet business.

Sikandar, however, was different. Upon completing his college education at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) Karachi in 1982, he started off as a photographer and a filmmaker. Whilst pursuing this passion he made a livelihood by conducting training sessions in photography, in addition to creating films for the corporate sector. A religious experience soon after college, however, persuaded him to give up photography and filmmaking.

In the meantime, however, Sikandar stumbled upon a talent for making spice mixes. In the late 1970s, in the absence of air-tight jars that could keep out the humidity, households would keep jars of common combinations of spices in solidified masala patties in their homes, breaking off a small piece to add to food during cooking.

While he was still young, Sikandar’s mother traveled to Lahore for a few days, and in her absence, the household ran out of the masala patties. His sisters tried to replicate his mother’s recipes, but were unsuccessful. Frustrated, his father asked Sikandar to give it a try, and he had better luck. That was the first time Sikandar considered going into the spice business.

However, despite his amateur success, it was his wife who was instrumental in helping Shan get off the ground. Sikandar and his wife started making masala mixes in an empty servant quarter that they converted into a home office in 1981.

“In the beginning, we started off as a one-room operation where my wife and I spent countless hours perfecting our recipes. From the get-go, the response was great, maybe because he launched right before Eid, a time when most people buy masalas,” said Sikandar, in an interview with Profit.

As business took off, Sikandar needed capital to expand, and turned down an offer from his father to help provide the necessary funds. “I sold everything I had except for my shoes,” he said. The bulk of the initial capital for Shan, however, came from the family-funded real estate business that Sikandar – like many upper middle-class men – had: buying and selling properties, using part of the profits to fund Shan Foods’ operations.

“My wife is the custodian of the recipes,” he said. During the initial days, Sultan and his wife would go in and mix the masalas themselves. “Now that the business has expanded to such a level, we do have certain highly trusted members of the team who know what ingredients we use and what the perfect ratios are that make our recipe mixes distinct. There are no secret ingredients.”

The recipes themselves are a product of the cultural background of the couple. “While I am Sindhi because I was born in Karachi, my family migrated from Delhi. My wife’s family migrated from Bombay.” Both regions have deep traditions of spice mixes unique to Muslim families that were originally developed in the kitchens of Mughal emperors and nawabs. That specific regional origin may play a role in the market positioning of the company today.

“Taste preference is definitely something that results in brand loyalty. You can see this in how we are a market leader in Sindh but not in Punjab because of their varied taste palate. So definitely taste preferences surely does play a big role in brand loyalty,” said Sikandar. And that certainly stands to reason: Muhajirs from Delhi, Bombay and other areas of Northern India primarily settled in Karachi and Hyderabad after Partition and may prefer Shan because it tastes similar to their family recipes.

Fast forward to the present, Shan has grown manifold. Far from being a one-room operation, it has manufacturing facilities in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

“We have about 88 different recipe mix masalas. Out of these, our top running mixes across the globe include Bombay Biryani, Karahi, Achar Gosht, and Korma. We are now a global brand, present in over 75 countries, and we have a strong resonance in terms of top of mind recall with the kind of communication that we put out,” said Sikandar.

The company’s impact on Pakistan’s corporate landscape is quite literal: the roundabout on Korangi Road in Karachi near the Shan office is called Shan Chorangi.

Yet despite all that growth, Shan Foods’ aversion to external capital sources remains a constant, particularly avoiding debt. “We’ve never taken a loan out for the business. Religion plays a role in this but also the fact that we do not make profits our lifestyle. We reinvest that into the business,” said Sikandar.

That austerity may have worked well in the past, but the market today is tougher than it was when Shan first started in the early 1980s. And while Shan has grown significantly over the last several decades, and remains the market leader in masala mixes, it is not the biggest company in the broader condiment market. That would be the publicly listed National Foods, which is not only larger, but also growing faster and, more worryingly for Shan, evolving somewhat better with the market.

Specifically, the main source of growth for the Pakistani condiments industry is to serve the increasing Pakistani diaspora, particularly in North America. And on that front, Shan is losing badly.

North America: the battleground for the Pakistani condiment market

As we stated earlier, Shan has a higher market masala mix market, but National – by virtue of its larger product line of condiments such as ketchups and achaars – has had higher aggregate revenues since at least 2009, the earliest year for which Profit has been able to obtain financial data for both companies.

If you look at the aggregate numbers, the disparity is not that huge. On a consolidated basis across all subsidiaries, Sikandar says that Shan’s revenue in 2020 was approximately Rs24 billion. That is smaller than the Rs29 billion in revenue for National Foods that same year, but not worryingly so. The problem appears once one drills down into the details of the numbers.

While the spice market within Pakistan is growing respectably, the key driver of growth has been exports to serve the Pakistani diaspora overseas, specifically the one in North America, driven by everyone and their cousin moving to Canada. For both Shan and National Foods, revenue growth in exports has consistently been higher than that of local revenues in five of the six years between 2013 and 2019, the latest period for which Profit was able to obtain detailed financial data for both companies.

However, National’s share of the export market has been growing significantly faster than that of Shan, a fact that can best be summarised with a single statistic: in 2013, Shan exported more than twice as much as National Foods in terms of revenue, but by 2019, the numbers had reversed, and National exported nearly twice as much as Shan.

The numbers are not paltry: in 2019, Shan Foods exported Rs5.6 billion worth of products, mainly to North America, while National Foods exported Rs9.4 billion. Shan does not break out the precise geographic mix of its exports, but does state that North America is its most important market.

“Our North American market is the biggest one for us, making up for the largest segment of our international consumers,” said Sikandar.

National Foods, being a publicly listed company, offers significantly more detail about its exports. In 2020, exports to the United States and Canada accounted for 92% of all exports by National Foods. And if National Foods’ numbers are a reasonable proxy for the market (and we at Profit, based on the National data and commentary from Shan’s management, believe that they are), then exports to North America drive a plurality of the growth in the market for Pakistani condiments.

Here is how it breaks down at National Foods: between 2015 and 2020, National Foods saw an increase of Rs22.9 billion in gross revenues. Of that, Rs10.3 billion – 45% of the total – came just from the rise in exports to the United States and Canada. The domestic market accounted for Rs12.5 billion. Yes, those numbers are correct: growth in exports to serving Pakistani expats in North America nearly equaled the growth that came from serving 200 million Pakistanis living inside Pakistan.

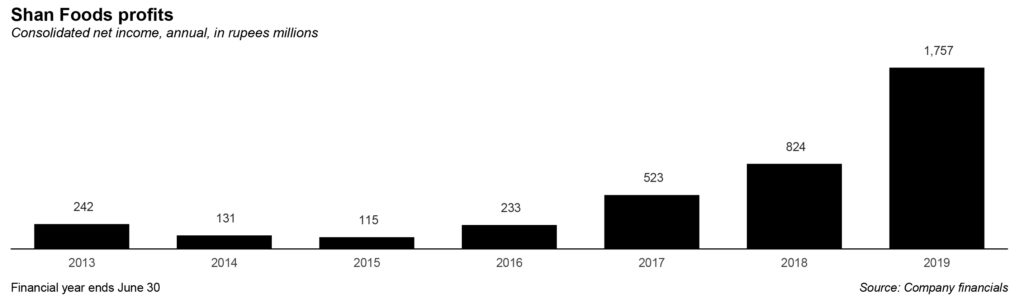

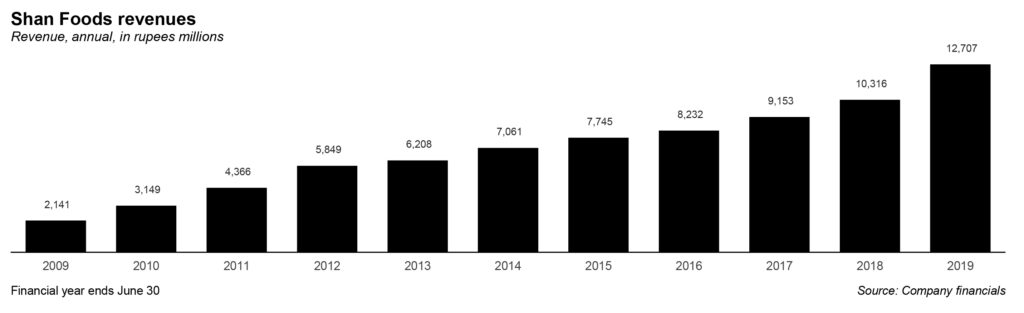

That spectacular growth in North America has been powering National Foods to grow faster than its rival Shan. In the five-year period between 2009 and 2014, Shan was handily crushing National Foods in terms of growth numbers, posting an average revenue growth rate of 27% per year during that period.

That was before National turned on the turbo-boost engine on its North American sales. As recently as 2015, National sold just Rs391 million worth of products in the United States and Canada combined. Since then, however, its growth has skyrocketed. In the subsequent five-year period spanning 2014 through 2019, National has handily beaten Shan in revenue growth, averaging a 20% per year growth rate compared to Shan’s more modest average of 12.5% per year.

It is true that Shan owns some manufacturing and trading facilities abroad, which may artificially decrease its numbers somewhat, but even by the numbers that Sikandar gave Profit for the company’s global consolidated sales, National has higher revenues than Shan: Rs29 billion for National to Rs24 billion for Shan.

And the details in Shan’s financial statements indicate that the bulk of its manufacturing abroad still relies on ingredients exported from Pakistan, numbers that show up as export revenues for the Pakistani company, suggesting that the foreign subsidiary’s earning power is largely accounted for in the Pakistan numbers.

This is not to say that Shan has not had wins in the international market, particularly on the branding front. In December 2020, Gigi Hadid’s featured her spice collection on her Instagram stories, which included a few boxes of Shan masala. This, of course, is not entirely accidental: Gigi’s partner is Zayn Malik, formerly of British band One Direction. Zayn’s father is of Pakistani origin and Zayn himself grew up in Bradford, which at this point is more Pakistani than Chak Shahzad.

“It was in fact heartening to see that a famous personality like Gigi Hadid is a part of our loyal consumer base across the globe. Such exposure brings more awareness to the brand and its effect cannot be measured in a short period,” said Sikandar.

That branding win aside, however, the money is in getting on the shelves of Walmart in Mississauga. And on that front, National appears to be ahead. How did National manage to turn the tables on Shan Foods? It is our contention that National is helped by being a publicly listed company, consistently accountable to minority shareholders – including long-term foreign shareholders like the Singapore-based investment firm Arisaig Partners – who view National Foods as a growth stock, and therefore demand that it continue to invest in expansion and growth opportunities.

Public vs private: a difference of perspectives

The public company has fallen out of favour in recent years in the United States and Europe, but the corporate form retains several advantages, foremost of which is transparency which brings with it a level of scrutiny and accountability that, at its best, can spur a company’s management to perform at their best. This is not to suggest that well-run private companies cannot do just as well, or even outperform, their public counterparts, but merely to suggest that there is more pressure to perform well in a public company.

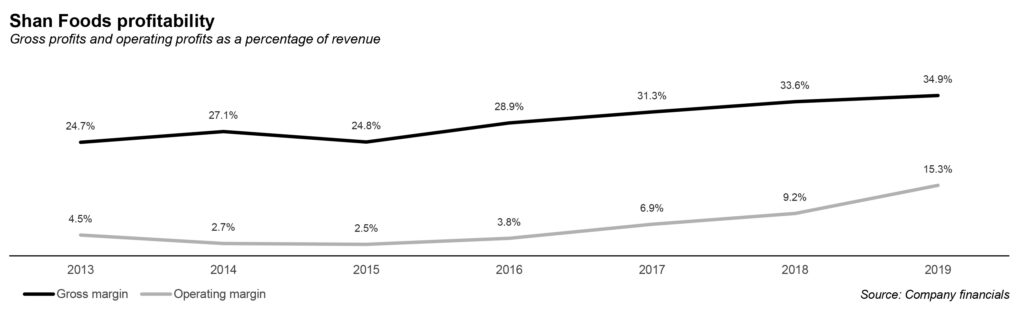

And, to be clear, Shan Foods is a well-run private company. Its management pays itself salaries that are well within the norms of comparable companies their size (perhaps even slightly on the lower side) and Profit’s revenue of their detailed financial statements from the past five years did not turn up any of the kind of lucrative perks that the owners of private companies often pay themselves.

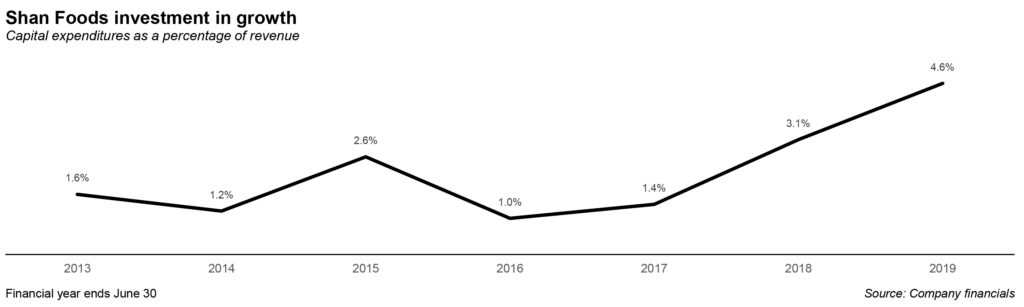

There are also no unnecessarily large dividends either, with the company dutifully plowing back a respectable amount of its free cash flows into the business. Measured by capital expenditures as a percentage of earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA), Shan Foods reinvested a healthy 28.4% of its free cash flows into its own business during the five-year period between 2014 and 2019.

No, Shan’s problem is not that it is not well-run, just that its competitor is doing even better. For instance, while Shan does well in terms of reinvesting for future growth, National does even more: capital expenditures as a percentage of EBITDA at National averaged 58% during the same period.

And it is not just things like capital expenditures. National is clearly willing to get aggressive in terms of its growth strategy in other ways as well, pulling all sorts of levers to ensure its ability to command a greater share of its target markets. For instance, between 2015 and 2018, the company doubled its spending on marketing and distribution – even at the expense of temporarily depressing its operating profit margin – in order to be able to achieve the kind of international growth it wanted.

Again, Shan has not been a slacker in spending on marketing and distribution. It just faces a more aggressive competitor.

What does National being public have to do with its aggressive stance on growth strategy? National’s management own only about 39% of the total stock in the company compared to 82% of Shan’s shares owned by Sikandar and his family. National’s management, in other words, are more vulnerable to irate shareholders demanding changes to the way they do things, and generally value being viewed positively by their institutional shareholders.

Shan’s management, by contrast, face less pressure and thus act with less urgency, a factor that shows up in the relatively lower levels of investment into growth compared to their rivals.

Then there is the approach to succession and control over growth assets. Shan – unlike many other family businesses – does not have the problem of the next generation being uninterested or incompetent at running the family business.

Sikandar’s daughter and son-in-law, for instance, have started a new brand of sauces called Dipitt, The brand is doing very well with Pakistan’s upper middle class consumers as well as restauranteurs, and the couple – emulating her father – have gone on to build on that success and opened Wingitt, a chicken-wing-themed restaurant that utilises sauces developed by Dipitt.

Both Dipitt and Wingitt are a natural extension of Shan’s product line and the fact that they came from the next generation of the family’s owners is even better. The problem? Neither Dipitt nor Wingitt are owned by Shan Foods the company, but instead a separate company that is owned by Sikandar’s daughter and son-in-law. The best innovation coming out of Shan will not be part of the company itself.

Compared to that, National’s new business lines – including its new packaging business called A-1 in Canada – all of which have been added as wholly-owned or majority-owned subsidiaries to the publicly listed company, thus adding to the company’s strength.

Of course, one model is not necessarily better than the other: the difference in public and family-owned business models is one of perspective. The National management see it as their obligation to forward the interests of the company, whereas in the family-owned Shan, there is an additional layer of concerns about family well-being and relationships.

Why a public listing could solve (many of) Shan’s problems

Shan’s management – and its chairman Sikandar – are of course intimately familiar with every issue we have laid out above, in greater precision and detail than we have. And they have publicly toyed with the idea of an IPO. As far back as January 2014, the company participated in the Pakistan IPO Summit, organised by the country’s leading investment banks as a conference meant to increase interest in public listings by prominent private companies.

And in a May 2018 interview with Profit, CEO Sikandar Tiwana said: “We are definitely considering an IPO… we are evaluating the advantage of an IPO. Do we need the funds, is the question.”

But in the most recent interview, conducted by Profit in March 2021, Sikandar said there was no plan to list the company. “We’re exploring our procedures and systems. However, there is no plan for an IPO. We don’t want to lose our control, nor do we have a major project in mind for which we need public money.”

As is indicated in both statements, the company’s board and management are both looking at the question of an IPO as one of whether or not they need the money. That, in our opinion, is too limiting a question to ask. Instead, the broader question should be: Would a publicly listed Shan Foods be a stronger company than a private Shan Foods? In our view, the answer is yes.

There are three main advantages of doing so: succession planning, incentives for management, and better recruitment that comes with the greater visibility of being public.

Firstly, Shan is clearly going through a transition as Sikandar has effectively moved into a semi-retired phase after having spent over four decades building out a strong business. He has handed over management to a professional, non-family management, led by Tiwana. That whole process of a new management taking control would be much easier if the equity being offered as incentive to that management was publicly traded and had a price they could easily look up and calculate.

Secondly, and relatedly, even if the management is given shares in a private company, it is not as powerful an incentive as shares in a public company, which offer both transparent pricing and ease of liquidity: if the managers need the money for personal reasons, they would easily be able to cash it out.

And lastly, if the company wants to remain an engine for innovative products after its founders move on to other things and their heirs build businesses of their own, it needs to attract the best talent. And the only companies that attract the best talent are either the multinationals, or else publicly listed local companies.

In short, when faced with an aggressively expanded, publicly listed competitor, Shan Foods can no longer afford to remain private. Even if it does not have a specific plan of what to do with the money, it should raise the capital anyway. Money has a way of finding uses for itself. But in the condiments business, National Foods has now made being publicly listed table stakes. Shan either needs to call the bet, or watch its competitive position slowly be eroded away. One of those options is clearly preferable to the other.