To a person living in a remote area where bank branches are few and far between, it is a blessing. To law enforcement, it can be a nightmare. The mechanism in question is hundi, also known as hawala, an Arabic word which means transfer. In common parlance both words refer to an alternative channel to send money that operates outside the formal banking system.

This ‘shadow banking’ system has existed for centuries, and will likely not go away anytime soon. Profit explains what hundi is, how it is conducted, what the problem with it is, and why it is hard to get rid of.

How does hundi work?

Hundi is an informal way of transmitting money from one country to another without using a financial institution, such as a bank or a money exchange. It has been operational for centuries, but as concerns arose globally about its potential use in money laundering and terror financing, some countries, including Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, outlawed it. On the other hand, countries such as the United Arab Emirates with a large number of foreign workers, regularised it.

The hundi business is based entirely on trust and relies on a network of Hundi dealers (in Arabic, these dealers are known as Hawaladars).

Let’s say you are a Pakistani working in Dubai and want to send a portion of your salary to your family member back home in Karachi. You go to a Hundi dealer, Mr A, and inform him about the amount you want to send and the city. You and Mr A agree on a password or code, which you will tell to the family member.

Meanwhile, Mr A contacts another hundi dealer, Mr B, who is based in Karachi, and informs him about the amount and the password as well. Your family member will then go to Mr B’s shop, tell him the password and receive the amount. This entire process can be done as soon as a few hours and requires little to no documentation. The dealers will settle their accounts at a later date either through money or goods.

Remitters choose hundi primarily because of its speed and low cost compared to financial institutions. According to the International Monetary Fund, discussions between officials have “tended to confirm that this system often has advantages compared with banks, money exchanges, Western Union, MoneyGram, and other providers of this service”.

The World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief released in June 2023 also confirms this. According to the report, banks are the costliest channel for sending remittances, with an average cost of 11.8%, followed by post offices (6.3%), money transfer operators (5.4%), and mobile operators (4.5%).

Hundi can also be an attractive option because it may provide better exchange rates compared to the official ones, especially if the government has imposed a cap, such as when it did in September 2022 (the cap was lifted in January 2023).

Since it is an informal system that does not require documentation, hundi also becomes a far more viable option to send money to relatives in far-flung areas, or those who cannot access the banking system.

There are two types of hundi dealers. The first type already run cash-intensive legitimate businesses, such as travel and tourism, gold, import and export, or foreign currency trading. In this case, they are able to ‘mix’ their legitimately earned money with proceeds from their hundi business, and can even make it a part of the formal system through international payments or transfers for their legitimate business.

Zafar Paracha, general secretary of the Exchange Companies Association of Pakistan (ECAP), elaborated the role of jewellers in the hundi business. He said jewellers who were a part of the hundi network would give the recipient the money, and receive payment from the other hundi dealer in the form of gold. The original dealer would send or smuggle gold to the jeweller, with the latter claiming that it was simply sent from a country such as the UAE so he (the jeweller) could modify it and add value, and then “export” it back. In reality, however, the jeweller or local hundi dealer would get fake documents showing the gold had been ‘exported’; it was later sold in the market, according to the ECAP general secretary.

“The entire gold business in Pakistan is unregulated. There is no bank transaction or money trail for such instances,” Paracha said, adding that when the government launched a crackdown on illegal foreign exchange trading in September, people had initially gone to gold jewellers who also dealt in it, which is why the crackdown was later expanded to the gold sector.

The second type of hundi dealers are those directly involved in just illegal foreign exchange trading.

Both types make their money through fees (which are lower than the fees charged by banks and money changers), and by bypassing the official exchange rates.

Hundi dealers settle their accounts in several ways: through future reverse transfers, import or export of goods, smuggling, or property purchases on behalf of the receiving dealer (to whom the money is transferred) in the country the money is sent from.

Hundi’s popularity in Pakistan

Shahid Mehmood, an economist and research fellow at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, explained that hundi is a trust-based system that has historically catered to the diaspora, particularly the manual labour force in Gulf countries, whose hometowns have lacked viable banking services.

“For example, in erstwhile FATA, now part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, there is still little presence of formal banks, which is worsened by very poor service standards. Cash, for example, is often in short supply in the branches there, and the security situation is such that going to a bank carrying cash is a risky venture. So, why not avail the services of a reliable person in the area, who has got loads of cash stacked at his place?” he questioned rhetorically.

He added: “The relative or family member working in a foreign country can pay that reliable person’s relative there, and in return, his family members avail ready cash without all the hassle and risk associated with availing a bank’s services. Additionally, anonymity remains intact, which could be of real value not only in far-flung areas of the country, but also in risky cities such as Karachi where extracting cash from ATMs or carrying cash from banks increases the risk of muggings substantially.”

After all, the system became popular in South Asia centuries ago mainly because of security concerns. According to ‘Ancient Banking, Modern Crimes’, a research paper by Joseph Wheatley, hundi became famous in the subcontinent because it removed the inconvenience of carrying large amounts of cash and the risk of robbery for Arab traders travelling along the Silk Road.

In more recent times, Mehmood said, some of Pakistan’s biggest foreign exchange firms initially started out as small hundi businesses. “It is not that their business was not known to the governments at the time, but that they generally turned a blind eye since dollar inflows were not a big issue back then [during the Soviet-Afghan war]. However, as it came to an end, dollar inflows dried up, and the issue of terrorism took centre stage. This brought pressure to close down informal channels, and there was this sudden urge to preserve as many dollars as possible to shore up reserves as inflows dried up. It was at that time that the first big wave of formalising the ‘hundi companies’ began.”

He added: “However, one would have to be really naive to believe that the same companies have completely given up their informal channels. Just as ordinary folk always take the prevailing risks into account, forex suppliers such as these companies do as well. The biggest risk comes from government policies, especially from policies like the ones followed assiduously by [former finance minister] Ishaq Dar,” he commented.

“His infatuation with controlling the forex rate through administrative actions created a huge gap between the market and the administered rates, as we witnessed recently during the time of the PDM government. No forex company or bank would like to sell at official rates given such a wide gap. In the case of forex companies, they revert to long-established informal channels, something that the government finds difficult to track. In other words, keeping informal channels open is a kind of an insurance for these companies against administrative measures that could lead to losses on forex exchange.”

An official at the Federal Investigation Agency, who covers financial crimes, also told Profit that whenever there is a wide difference between the rates in the interbank and open markets, or the exchange rate is artificially fixed, hundi transactions start rising as the dealers offer better rates.

He also explained that while one of the primary purposes of hundi in cities such as Peshawar and Quetta was smuggling, in Karachi, it was trade-based transactions. “For instance, an importer wants to get solar panels or clothes from abroad. He undervoices the payment [to dupe] Customs officials and pays half of it through formal channels and the rest through hawala. He gets a few benefits: he is able to buy dollars for cheaper, he doesn’t have to do the complete transaction through a banking channel as he has cash on hand which he has not declared, and he also has to pay less duties. So, it’s a very convenient situation for him. This is why a portion for almost all imports, other than those by large, registered firms, is done through hawala,” he added.

The problem with hundi

While hundi may have some advantages, especially for countries with underdeveloped banking systems, there are several concerns, including exchange rate manipulations, money laundering and terror financing.

For a country like Pakistan, when inflows in the form of remittances are not sent through formal channels, it affects the foreign exchange reserves, which in turn puts pressure on the exchange rate, and the current account deficit.

[For those who may be a bit bewildered about what this means: when remittances are not sent through legal channels or the amount is low, the foreign exchange reserves are affected and a shortage of dollars in the legal currency markets emerges. This weakens the rupee, since the demand for dollars outstrips the supply, making the latter more expensive. And since the foreign currency is not being sent via legal channels, official data shows a widening gap between all the money Pakistan earns through exports and remittances and the money it loses through imports and loan payments (called the current account).]

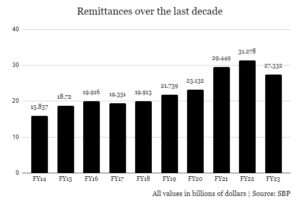

In 2022, when the government imposed an artificial cap on the dollar to rupee exchange rate, a large chunk of remittances were diverted to the hundi market. This was one reason annual remittances in fiscal year 2023 fell for the first time since fiscal year 2017. Last fiscal year, remittances declined by $4.25 billion, with analysts and currency dealers attributing it primarily to the hundi market.

Since the hundi market was offering much better rates — up to Rs 25 more per dollar — than the interbank and open markets, buying or selling of currency was also diverted to it, creating a shortage of dollars in the legal currency markets.

In the first week of September, law enforcement agencies launched a crackdown against illegal foreign exchange trading. Dozens were arrested in one month alone. A PTV report shared on October 1 stated that 239 people had been arrested across the country in September over hundi and currency smuggling. According to a report from APP dated November 3, the crackdown is still ongoing.

What do the laws say?

Hundi is illegal in Pakistan under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) of 1947, which prohibits any person not authorised by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) from trading in foreign currency. Section 23 of the Act states that anyone found to be involved in illegal foreign currency trading shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years or with fine or both. In addition, the law states that any currency found with such a person shall be confiscated.

Since illegal foreign exchange trading, especially if the transaction spans two or more countries, is also considered money laundering, the Anti-Money Laundering Act 2010 is also applicable. It states anyone convicted of money laundering shall be punished with rigorous imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than one year but may extend up to 10 years and shall also be liable to fine which may extend up to Rs 2.5 crores and shall also be liable to forfeiture of property involved in money laundering or property of corresponding value.

If that money laundered through hundi ends up being used for terror financing, then the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 will also be applicable, which lays out different punishments for different crimes.

Why is it so hard to eliminate?

According to the FIA official, eliminating hundi is difficult, because the crime in question is highly organized, and it is hard to present evidence for it in court. “There are no specific places where these dealers conduct their business, and we can simply go there and arrest them. These are ordinary people. If we arrest someone, we have to show that the person had dollars [or other foreign currencies] in his possession, and that he was doing hundi,” he said.

“What can this evidence be? Consider how hundi transactions are done. You give your local dealer the money and he asks his offices in the US, UK, or UAE to give that money to whoever you wanted. Around 10 to 15 years ago, the dealers would maintain registers, which we would seize and we would say, ‘look here is the evidence of those transactions’. Those registers are no longer there.”

As digitisation increased, hundi dealers methods of recording transactions changed. This makes it much more difficult to collect evidence, the FIA official said.

Another problem, he continued, was that the law was outdated. FERA does not explicitly define hundi, and states that the person can be jailed or fined or both. “The law is weak. The judges are not aware of [the scope and complexity of] hundi either. They will know what it is by definition, but our society in general does not consider hundi a crime. The judges do not really understand this crime or its consequences, and there is societal support for it.”

The FIA official said that in his knowledge, no one has ever been imprisoned after being convicted of being a hundi dealer. The fines are not prohibitive as well, he said, adding that the money recovered from the arrested dealers never makes it to the treasury because the law does not have a specific provision for it.

“In a way, we are only a deterrent. We arrest the person and give them warnings,” the FIA official said. The weak laws and the judiciary’s limited understanding of how hundi can be harmful for the economy or eventually result in financing of a terror attack is one reason the illegal trade has continued to exist, and at times, thrive.

He said the onus to crack down on hundi dealers also lay on customs officials, who should be more vigilant about under and over-invoicing issues. “Let’s say a company requests SBP that it wants to remit dollars abroad for imports or services, but the central bank refuses. However, the transaction still happens and imports are received or services are taken. Nobody investigates how it happened. Of course, the transaction was done through hundi.”

“This is not about one institution. The problem is everywhere,” he pointed out.

The SBP, FIA, and Customs would have to work together to ensure that hundi is minimised, if not eliminated. However, as the official himself noted, “hundi had, in a way, become a necessity for the country.” He was, perhaps, referring to the import restrictions imposed by the PDM government last year shortly after coming to power, and which were eventually completely lifted in June 2023.

“The laws need to be updated. It is not one institution’s job,” he iterated. “Hundi is a transnational crime. It originates in one country and ends in another. It does not only happen in Pakistan but other countries as well,” he said, bringing up the UAE specifically – the Gulf country mandated hundi dealers to register in 2020. Thus, efforts to end hundi would by necessity have to be international.

Thanks For this information i really like it

Assalamolaikum