This is the story of a rise, a fall, and possibly a second act. Over the past fifteen years the Chenab Group has faced a gamut of challenges. Once one of the largest exporters in Pakistan, and owner of the popular ChenOne stores locally, they faced consistent losses as the country’s textile industry suffered in the aftermath of the 2008 energy and financial crises.

Many waited and watched to see when Chenab and its owner, Mian Muhammad Latif, would call it quits. However, either completely through an act of inertia or through sheer determination, somehow the vertically integrated textile exporter clung on. And now an opportunity may just have presented itself from unlikely quarters.

The company has been given some quarter to breathe thanks to its lenders. Amongst them, HBL was Chenab’s biggest lender. And now the bank is spearheading the restructuring of the company’s Rs 10 billion overdue debt to the banking sector.

There seems to be belief within HBL that the Chenab Group will succeed in turning their company around. Where does this faith come from? It might have something to do with the company’s origins and its history.

Big dreams

We start off in Toba Tek Singh. With a young man and a big dream. Mian Latif was the son of a leading cotton industrialist. Latif’s family had come to Toba Tek Singh back in 1883 and were agriculturalists. In small towns like Toba Tek Singh, land-owning farmers realised cotton was an important crop for the ruling British Empire. And for much of his childhood Latif saw as his family’s fortunes grew. Within the tiny agricultural community, cotton farming and ginning were lucrative businesses. Mian Latif’s family were large landholders in Toba Tek Singh, a district roughly halfway between Faisalabad and Multan.

But as a young man Mian Latif’s ambition lay far beyond Toba Tek Singh. In the 1970s many of Punjab’s large rural land holding families were making a transition: moving their main source of wealth away from farming the cotton – and other crops, such as sugar – and towards setting up the industrial units that would process and sell finished goods. And for this purpose Mian Latif, along with three of his brothers, set his eyes on Lyallpur.

The city had still not been dubbed Faisalabad when Mian Latif first started establishing a business there in 1973. At the time the city was still developing and far from the industrial hub it is today. But Latif had a belief that his family’s future lay in manufacturing textiles rather than just farming and selling cotton. Remember, the 1970s were marked by mass nationalisation. The independence of Bangladesh in 1971 also meant Pakistan lost many of its industrial units and there were no exports to speak of.

Latif set about establishing a production unit which could not only manufacture but also export. The company started off by producing textile goods for the local market. In 1985 they began exporting goods starting from the Far East from where they moved to Europe and then USA, eventually exporting goods to around 42 countries.

Events leading up to the crisis

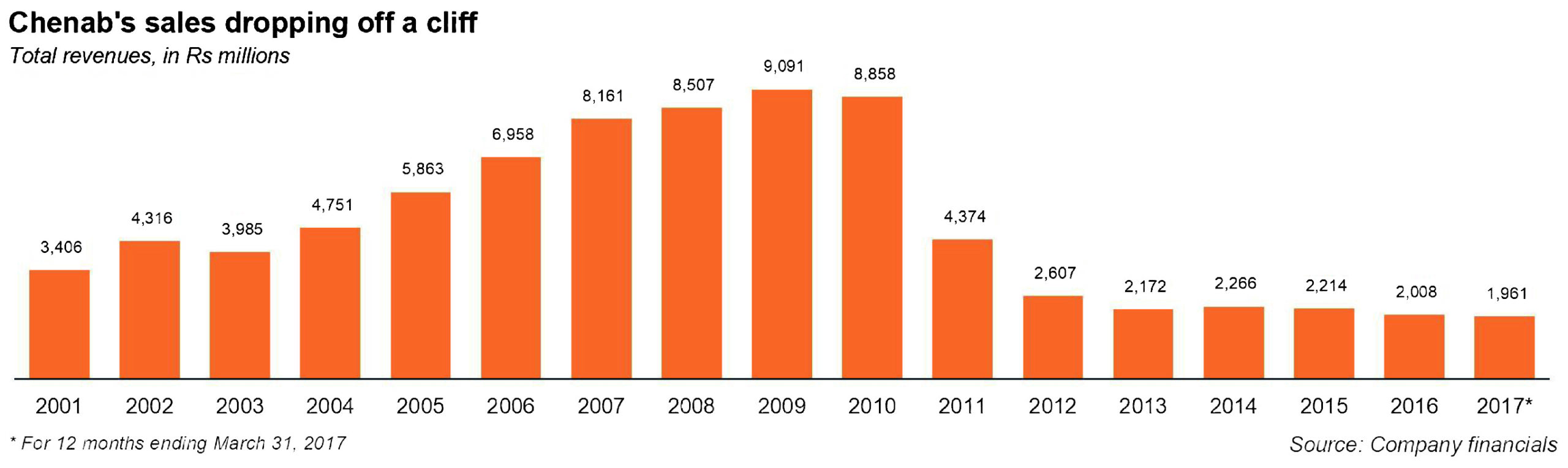

To understand the downfall of the company, it is important to understand the time leading up to the crisis. In 1999, when Gen Musharraf took power in a military coup, the Chenab Group was still a lower middle-market business in terms of size. And ChenOne at the time only had three stores, though its fourth store opened up in Karachi that year. During the Musharraf Administration, however, as the government privatised the banks and encouraged private sector lending, particularly for industrial growth projects, the Chenab Group started expanding aggressively. For the financial year ending June 30, 2001, Chenab Ltd, the group’s main publicly listed company, had revenues of Rs340 crores. Over the next six years, the company more than doubled its revenue, ending the financial year 2007 with Rs816 crores in revenue, which represents an average annual growth rate of 15.7%. At one point in time, the company was making $30 million worth of exports on a monthly basis and employed 12,000 people.

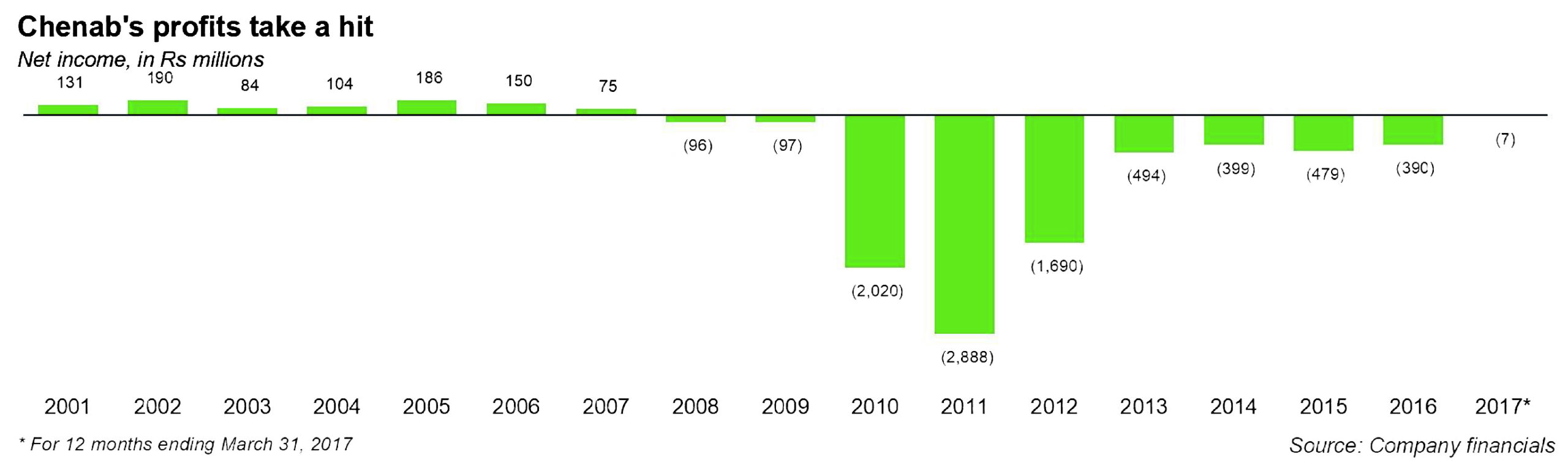

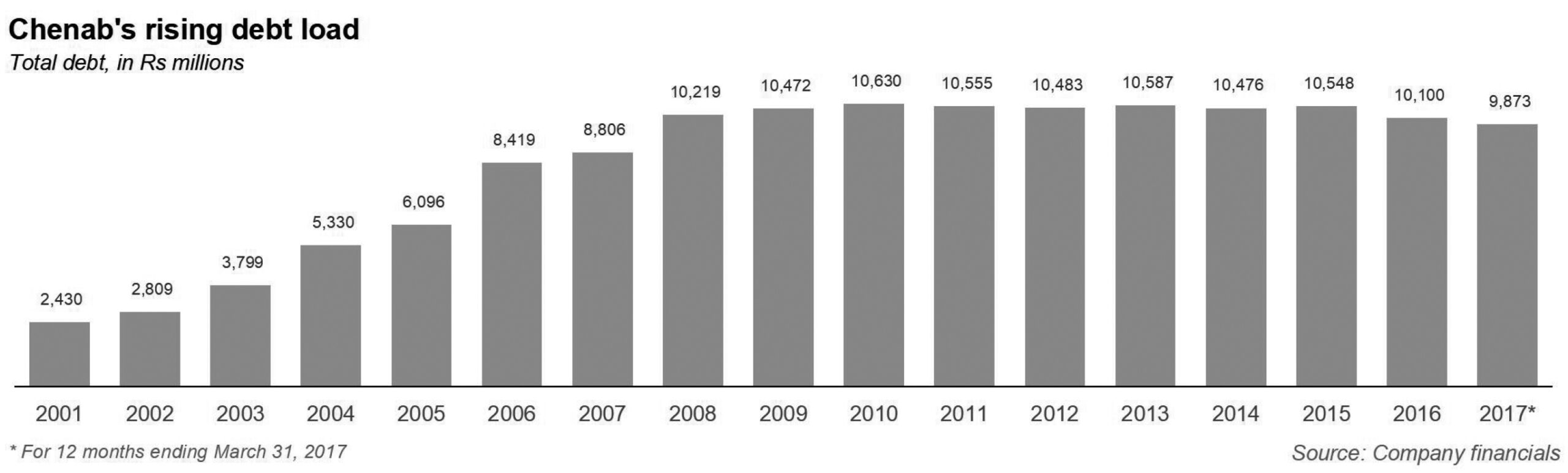

That growth, however, was fueled largely by debt. In 2001, the company had just under Rs70 crores in long-term debt. By 2007, that number had ballooned to Rs332 crores, a nearly five times increase. Yet cash flows were not keeping pace: Chenab Ltd’s net income in 2007 was just Rs7.5 crores, even less than the Rs13 crores it had earned in 2001.

Yet the group kept expanding, particularly its retail chain, which opened up more stores throughout urban Pakistan, particularly in the smaller metropolitan areas of Punjab, where it took to developing not just its own stores, but large shopping malls and complexes under the name ChenOne Tower. The first ChenOne Tower opened in 2005 in Multan, followed by another in Sargodha, which finally opened in 2009.

At the same time, even though the company was growing, stiff competition from China and India was being faced. These countries were providing subsidies to the textile industry while Pakistan had no such programme for its own industry. Not at the same scale, at least.

In domestic terms, the finance costs were already ramping up as interest rates were being used to address inflation which were also being translated to higher energy and labour costs. Even though profitability was down, it was expected that as the conditions would improve, the company would be able to rebound.

The crisis sets in

The year 2008 was supposed to be a stellar year, in terms of sales, for the company as it had already forecasted sales of more than Rs. 800 crores for the year. The company was able to earn revenues of Rs. 850 crores but it was the first year in decades that the company made a loss.

The cause for this was two events. First of all, the country started to see wide scale gas and electricity load shedding which forced production to slow down and created an added pressure on the costs being incurred. In addition to that, the assasination of Benazir Bhutto saw the whole country shut down. With railway lines and road infrastructure being impacted, exports stopped with containers waiting at the ports for days.

Between 2007-8 Pakistan was hit by the global recession. The textile industry faced challenges due to high energy costs, rupee depreciation vis-à-vis the US $ and other currencies, and a high cost of doing business. As a result, there was a reduction in the number of textile mills operating in the country from about 450 units in 2009 to 400 units in 2019. This decrease has simultaneously seen the domestic demand for cotton dip in the country.

The ethos of the company became a haunting call as the company was not able to follow through on its promise of commitment. Rising costs and fall in revenues were already having an impact on the company. However, something much more damaging was also taking place. Clients were not getting their orders and the trust that had been built bit by bit over years came crashing down in a matter of days.

Latif himself explains the situation thusly. “The trust we had built with the clients is built inch by inch. When it comes down, it comes down in meters.”

The loss of brand name and image for clients was going to have a devastating impact on the future revenues of the company and would have a long lasting effect. The period from 2009 to 2014 saw the company face consistent losses. The inertia built into the system saw sales of Rs. 900 crores in 2009 decline to only Rs. 220 crores by 2014.

As the losses started to accumulate, the equity of the company turned negative in 2011 and stood at minus Rs. 400 crores in 2014. In real terms, the company saw a loss of Rs. 730 crores in a span of 5 years which comes to around average annual losses of Rs 150 crores per year.

The impact of losses had a two fold impact on the company. At one hand, the company relied on taking on more debt in order to fund its working capital requirements in order to carry out some form of manufacturing. Even though orders had fallen, still the company needed to make sure it could retain some form of exports to the clients who had still stuck with the company. The company hit its lowest point when, in 2014, it announced that it would not be able to pay back its debt obligations which led to many of the creditors filing recovery proceedings against the company.

As the case proceedings started, Latif still felt that his dream should not die. Even in the darkest times, he had the belief that given the right support and resources, his dream will become reality once again.

In 2017, the Lahore High Court asked winding up proceedings to be initiated against the company in order to allow the banks to sell the assets of the company and get back some of their money. This would have felt like the end of a journey that started 43 years ago. Latif still persevered and fought. The case was litigated to the fullest extent and in 2021, the court reversed its winding up orders. The company was going to be allowed to operate once again.

The unlikely hero

In many ways Chenab is not unique. Like many of Pakistan’s upper middle-market companies – the ones just on the cusp of being large but not quite – Chenab tried to grow too fast with too much debt during the easy money era of the Musharraf years, and crashed hard after the financial crisis of 2008, and has yet to recover since. Yet unlike some of the other financial carcasses of the 2008 crash, the owners of Chenab have continued to try to revive their business.

It has perhaps been that tenacity that is now paying off. After some favourable bankruptcy case rulings in the Lahore High Court (LHC) back in 2020, the company has now found an ally in HBL. At this point, there were 22 creditors who had lent to the company. Among the biggest lenders was HBL. In such dire circumstances, HBL provided an opportunity for the company to get back up on its feet.

HBL spearheaded the effort to consolidate the total debt of the company and to restructure its short term borrowings to allow it to convert them all into long term liabilities. With assurances from the bank, the company felt that it could regain its lost glory and attain the heights that it once had.

The bank has also provided much needed backing to the ailing company. The Rs. 9.5 billion debt was restructured for a period of 14 years. The bank believed in the fact that once the company was given an infusion of fresh financing, it would be used to fund the working capital requirements of the company. This would allow the company to meet its current orders and any excess capacity could be used to further broaden its sales and profits.

In addition to the banks restructuring the loan, the directors of the company gave a loan of Rs. 42 crore and 50 lakhs to the company and it was decided to sell some of the non core assets of the company in order to fund the working capital requirements.

The restructuring plan

Based on the court filings, Chenab Limited contested that it will execute a revival plan for the company and its competitors in order to turn the company around. The courts had already ordered winding up proceedings to be started against the company on the back of recovery lawsuits filed by some of the creditors. The Chenab Group felt that in order to put any plan into action, the first step was to get a stay on the winding up proceedings. Habib Bank, the largest creditor, joined together with some of the other creditors to provide some breathing space to the company.

Chenab group had short term loans of Rs. 4.3 billion while its long terms loans stood at Rs. 5.1 billion. From this, Rs. 1.7 billion was held by Habib bank followed by United bank held Rs 1.3 billion, Bank of Punjab held Rs. 1.2 billion and Askari and Allied Bank holding Rs. 1.4 billion collectively. In addition to that, the Group also owed to an additional 17 banks and financial institutions namely BankIslami, National Bank of Pakistan, Albaraka Bank, Habib Metropolitan Bank, Silkbank, Standard Chartered Bank, MCB Bank, Citibank, Faysal Bank, Saudi Pak Industrial and Agriculture Investment Company, Pak Oman Investment Company, First Punjab Modaraba, Pak Libya Holding Company, Pak Kuwait Investment Company, Orix Leasing and Orix Investment Bank, First Credit and Investment Bank and First National Bank Modaraba.

The total debt of the company was going to be divided into two parts as Tier I and Tier II with both tiers having an amount of Rs. 4.7 billion each. The Tier I loan was going to be paid over 30 quarterly installments which would elapse a time period of 7 and a half years and would start from the time the proposal was sanctioned and put into place. Once the Tier I loans were paid off, the amount owed to Tier II would be paid off over a period of 6 and a half years with 26 quarterly installments.

The markup on the loan was set at 5 percent per annum for Tier I initially while during this time the Tier II will accrue markup at 3 percent until the Tier I loan was paid off. Once this was done, the markup on the Tier II loan would also rise to 5 percent until all of it was paid off.

In addition to that, the family also sold a third of its holdings of 60% to an investor in order to meet their working capital needs at a rate of Rs. 15.2 per share. This investment totalled to around Rs. 35 crore of additional funding which was used towards the company and its restructuring. The company also committed to selling some of its non-core assets which were expected to raise Rs 1.4 billion which would be used to pay off some of its loans while also look to meet the working capital requirements of the company.

Looking towards the future

The company seems to have turned the page. In the last 18 months, the company has been able to earn Rs. 2.5 billion in revenue and has hired 3,000 of its former employees back. It is a blessing for the 3,000 households whose futures and hopes are now attached with the future of the company again.

From the total loan of Rs. 9.5 billion, the company has already paid back Rs. 1 billion and expects to keep on track of the Agreement that has been made with the banks. This mirrors Latif’s words when he says that “We will give every drop of blood but will follow through on our commitment.”

An important fact that needs to be mentioned here is that, even though the company has been following the payment plan that has been agreed upon, the company according to Latif is yet to reach profitability. The performance of the last 18 months has shown promise, but the company still needs some time before they turn profitable in the long run. In addition to that, the company is a listed company and was trading in the stock exchange, however, as it has not filed its annual accounts, it was delisted and put into the default counter. The company is correcting that by publishing some of its financial statements and the latest accounts that can be accessed are from 2021.

Restructuring creditors/management might seen some light after depression. Short term borrowings/ long term borrowings needs to be paid.

In order to pay the debt company must earn enough not only to keep it’s working capital liquid but also need money to repay debt.

Business may fluctuate but payment of debt will remain same.

One do wish that company may get successful but history and experience tell it is difficult. Change of management and reduction of debt is the answer. Bankers have reduced mark up. Any hair cut taken by creditors. Not clear. Banks see some return of their bad money and lend good money only in the shape pledge. That will be problem to raise current assets and make them free for utilization in production/ sale to earn revenues.

Plant remained closed for long time. How the teething problems in running of plant will be addressed. You might have prepared rosy paper but reality is very difficult to face.

I believe as per restructuring conditions no further concession will be given. We can pray for the success but writing is on the wall.

Pure Scammers they’re .

Started venture in Food and education industry to sell franchise and franchisees failed miserably .Closed down all and now few left only company run

very well paid article to mislead Public, why don’t you have the journalistic ethics of stating facts,actually it was ” Seth Culture ” and poor governance which led to Downfall of Chenone

This is a very interesting article without amy evidences, banks opted for reduced markup because tjey were getting a very meager principal amount or may be they are losing money so they agreed now while analysing sponsors put not a single peeny in this business rather sale their stake on a hefty amount so after all who is losing certainly banks.

There are millions of victims of financial fraud every year – and the problem is getting worse. Yet, because financial fraud normally occurs out of public view, many victims feel isolated and ashamed. The United States Department of Justice estimates that only 15% of victims of financial fraud report the crime because they are embarrassed, feel guilty or think nothing can be done.

It’s typical for victims of financial fraud to experience all these emotions according to Dr. Traci Williams, a board-certified psychologist and certified financial therapist. She adds that victims may also feel angry, violated, anxious, shocked, sad, and hopeless. Moreover, even a small loss can have a profound impact on victims.

Be careful of people asking for your money or investment platforms promising huge returns. They lure victims into fake programs. I was scammed over ($345,000) by someone I met online on a fake investment project. I started searching for help to recover my money and I came across lots of recommendations on a Bitcoin Forum about RestoreChef an Ethical Hacker. I contacted him via his email on RESTORECHEF@GMAIL. COM and he helped me recover my stolen funds. If you’ve also been a victim, don’t hesitate to get in touch with him.

A fault on banks part why they lend so much money to a single institution, their risk department was sleeping or they were too busy meeting their lending targets

secondly, owners should sell their big houses, big cars and commercial properties and reinvest in their company to show they are serious in getting the company back on its feet rather than just selling some of their unattractive properties.

Article not showing the actual picture