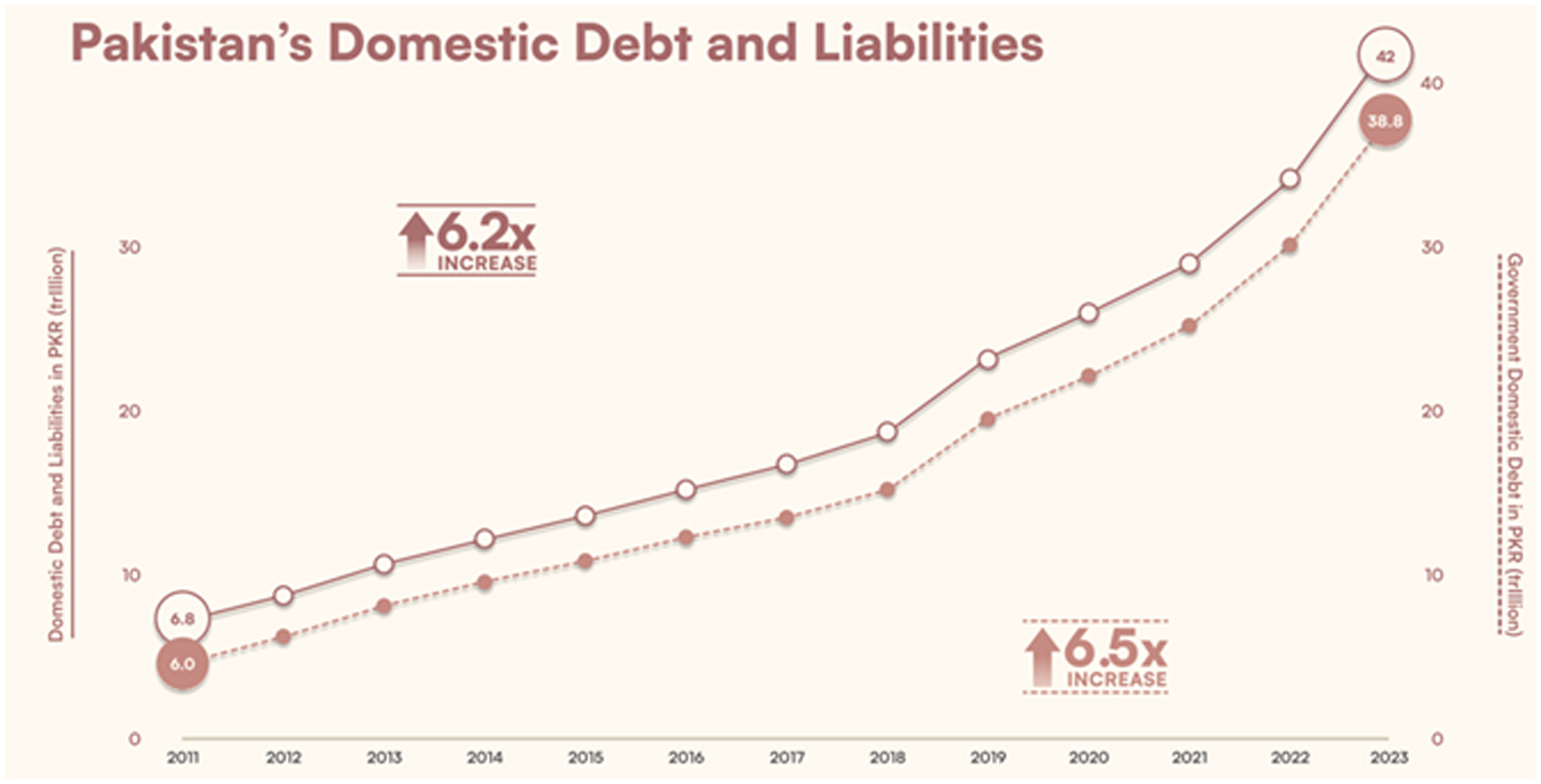

The debt dilemma in Pakistan has worsened as its borrowing has reached unsustainable levels. The escalation in debt, especially domestic debt, has been significant, surging by 6.5 times from 2011 to 2023. The details have been reported in a recent report by Tabadlab authored by Zeeshan Salahuddin and Ammar Habib Khan which describes the situation as “a raging fire.”

A matter of greater concern is that Pakistan’s debt burden is growing at a pace faster than the expansion of the economy’s net output (gross domestic product or GDP). This imbalance limits the economy’s ability to boost output. “This is unsustainable. It demands transformational change. Unless there are sweeping reforms and dramatic changes to the status quo, Pakistan will continue to sink deeper, headed towards an inevitable default, which would be the start of the spiral,” read the report.

Source: Tabadlab

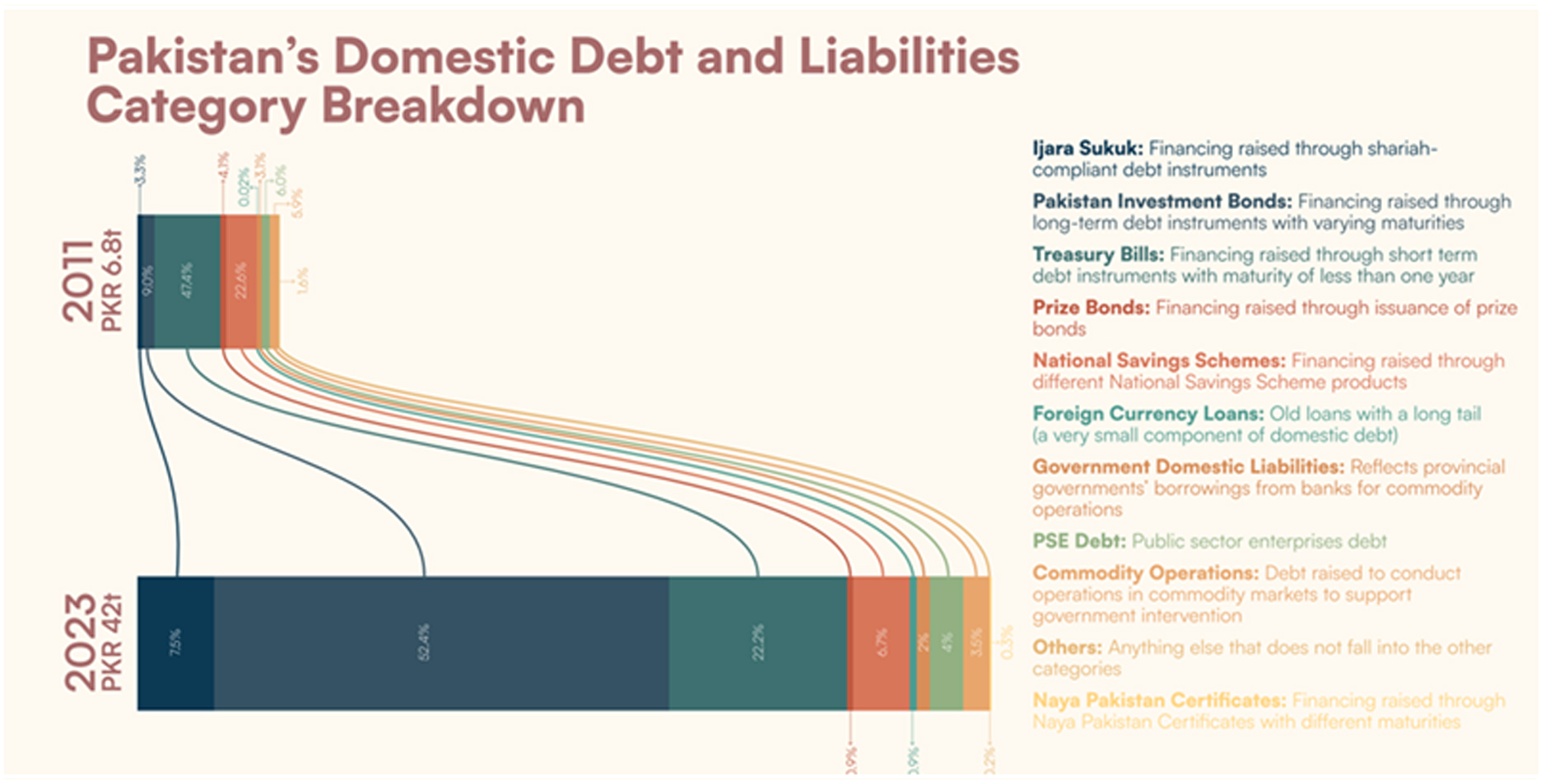

The government frequently engages in substantial borrowing from both domestic banks and international institutions to fund various expenditures, including ambitious infrastructure projects such as motorways. Domestic debt refers to the portion of debt owed to domestic creditors, primarily commercial banks. According to the think tank report, domestic borrowing is predominantly allocated to bridging the fiscal deficit, which arises from the disparity between government expenditure and revenues generated from taxes and other sources.

As per the report, in the last thirteen years, Pakistan has had a fiscal deficit every year. “Low tax-to-GDP and high revenue-to-debt-servicing numbers serve as the root causes for reduced revenues, and increased expenses, both of which contribute to the fiscal deficit.”

However, the government has surpassed the revenue target set for the first half of the current fiscal year. Despite this achievement, the fiscal deficit has been on the rise due to increased federal expenditure. According to the January 2024 report of the Ministry of Finance, the consolidated fiscal deficit stood at 2.3% of GDP (Rs 2407.8 billion) in the first half of fiscal year 2024 against 2% of GDP (Rs 1,683.5 billion) last year.

What explains this is the meteoric rise in the price levels. Average inflation in the first seven months of fiscal year 2024 has been hovering at 28%-29% which has increased spending as well, forcing the ministry to increase borrowing from banks. As per the Finance Ministry’s January 2024 report, total expenditures surged by 45% to Rs 9,261.8 billion in the first half of fiscal year 2024, compared to Rs 6,382.4 billion the previous year. This increase was primarily driven by a 41% rise in current spending (day-to-day operational expenses).

Pakistan’s domestic debt

At the end of fiscal year 2023, the government’s domestic debt stood at Rs 38.8 trillion. According to the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) latest debt statistics released on February 13, 2024, the government’s domestic debt stock has increased to Rs 42.6 trillion in December 2023, implying an increase of 10% in the first six months of the fiscal year 2024.

The government’s significant appetite for deficit financing through short-term domestic borrowing, coupled with record-high interest rates, has resulted in a dual crisis of elevated interest expenses and short maturity terms. Over the past year, the government has strategically focused on borrowing through T-bills and floating investment bonds (PIBs). Both options have led to substantial costs of debt servicing due to the prevailing high interest rates over the past year.

However, to address this issue, it appears that the government is now transitioning towards issuing longer-term bonds, which has been made possible by positive bids from market participants who anticipate forthcoming interest rate reductions.

According to the statement released by the Ministry of Finance on 22nd February 2024, the government was able to achieve a reduction of borrowing through government securities via the banking sector by 67% compared to the preceding period. The successful retirement of short-term Treasury Bills amounting to Rs 1.6 trillion further reduced the government’s gross financing needs.

Additionally, the caretaker government shifted its domestic borrowing to long-term debt securities, focusing on floating-rate securities while borrowing fixed-rate instruments at rates averaging 3- 4 % below the policy rate. This strategic move increased the average time to maturity of domestic debt to around 3.0 years by January 2024, aligning with targets set in the Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy.

Source: Tabadlab

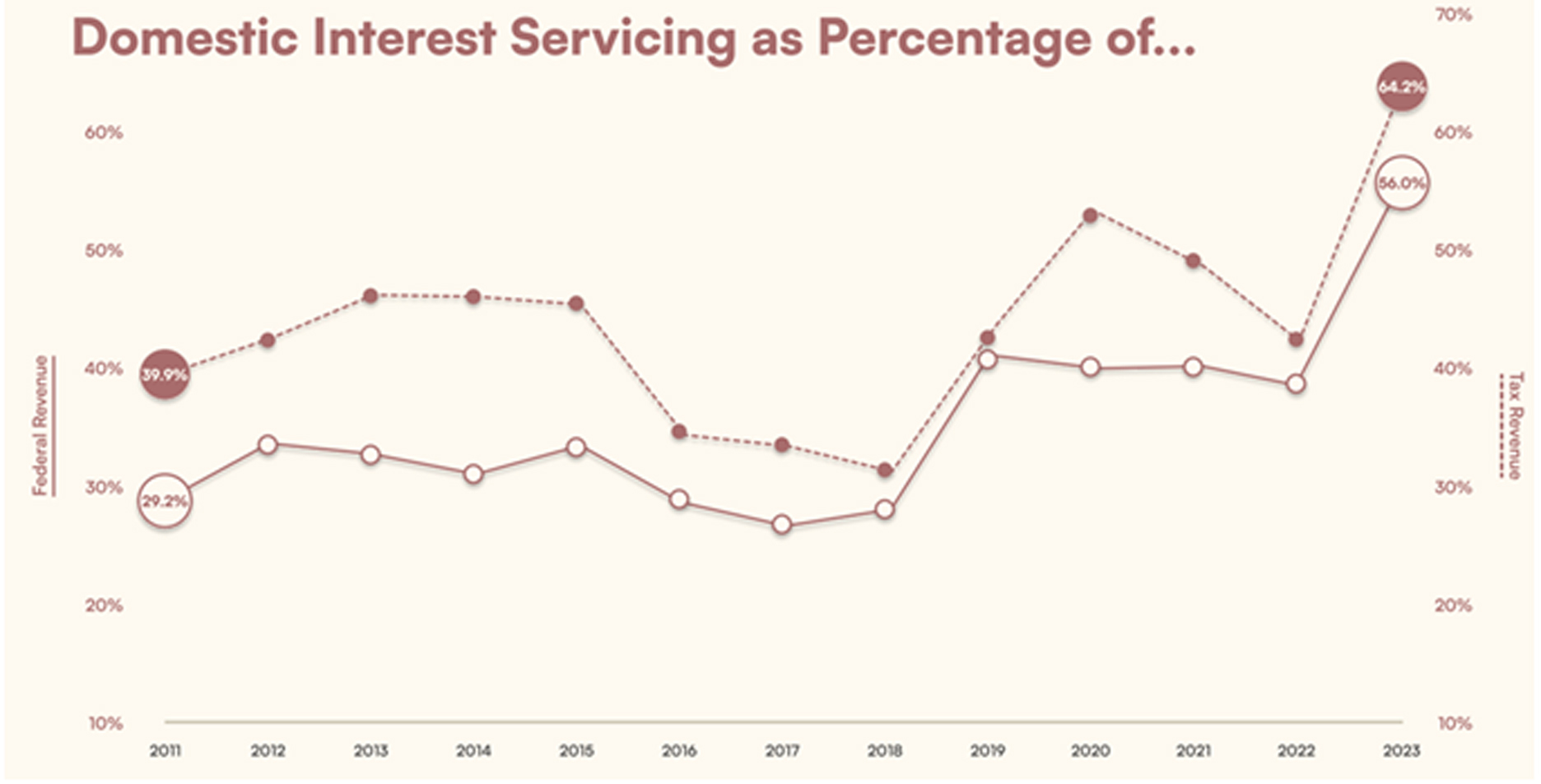

However, domestic debt servicing consumes over half of the federal budget, resulting in a significant fiscal burden. As per the report by think tank, in fiscal year 2023, domestic debt interest servicing as a percentage of federal revenue and tax revenue stood at 64.2% and 56% respectively.

This means since debt servicing is prioritised, other sectors that need focus are often ignored. Similarly, “Climate financing takes a back seat to domestic debt servicing, further deteriorating climate vulnerability profile,” read the report.

Source: Tabadlab

Who is responsible for high domestic debt?

The roots of this debt escalation trace back to previous administrations. In the last fifteen years (2008-2023), domestic debt has cumulatively grown at the rate of 18%.

Following the victory in the 2008 general elections, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) assumed governance in late March 2008. By the conclusion of fiscal year 2008, the domestic debt amounted to Rs 3.26 trillion. However, by the end of the PPP’s tenure in fiscal year 2013, this figure had surged to Rs 9.5 trillion, (almost 60% of the GDP) reflecting a substantial growth of 23.9% over the span of five years.

In June, the reins of government were handed over to the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N). By the conclusion of their governance in fiscal year 2018, the domestic debt had reached Rs 16.4 trillion. This indicates that during the PML-N’s tenure, the domestic debt experienced a growth of 11.6%.

The difference in debt pattern was explained by economist Uzair Younus in an earlier article for Dawn. “The PPP’s borrowing policy relied more on domestic than external borrowing. Much of this had to do with the prevalent economic conditions around the world, where the Great Recession significantly reduced the ability of economies like Pakistan to borrow money from the international bond market,” wrote Younus.

Following the victory in the 2018 general elections, the Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf (PTI) assumed governance in August 2018 until April 2022. During this time period, domestic debt increased to Rs 31.1 trillion, a cumulative growth of around 17% in four years.

Following the ousting of Imran Khan, the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) took charge. During their tenure, domestic debt escalated by 25% in just one year, rising from Rs 31.1 trillion in June 2022 to Rs 38.8 trillion in June 2023.

By the end of September 2023, domestic debt had reached around Rs 39.7 trillion, indicating a 7% increase under the caretaker government within four months.

Unfortunately, the bulk of debt accumulation has been used towards perpetuating a consumption-oriented economy with insufficient investment in productive sectors or industrial development.

Restructure domestic debt?

Experts believe that the country lacks the capacity to effectively manage the economic consequences of domestic debt restructuring.

In a previous conversation with Profit, economic analyst Ammar Habib Khan opined that the chances of domestic debt restructuring remain low. Instead, according to Khan, the government will be content with inflating away the debt due to gradually reducing the real value of domestic borrowing through the impact of high inflation.

Khan emphasised that the primary challenge does not lie in the current debt, but rather in the pressing need for liquidity to bolster reserves and support economic growth.

Similar sentiments were echoed by Yousuf Farooq, director of research at Chase Securities who opined that domestic debt restructuring is not required. In fact, he believes that domestic debt restructuring would permanently damage the financial system. Farooq emphasised on taxing untaxed sectors like agriculture and real estate instead of debt restructuring with the banking sector which already pays heavy taxes. The banking sector of Pakistan is one of the highest-taxed sectors in Pakistan, with effective tax ranging between 40-50% on average.

Shahid Kardar, former governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, wrote in his article for Dawn that banks might suffer as a consequence of domestic debt restructuring: “Banks being the largest lenders to a bankrupt borrower will also have to bear the burden of this pain. The reduction of this debt will require a gradual approach, involving a combination of negative real interest rates, a moratorium/suspension of interest payments for, say, two years, an extension of the maturity period and even some write-down of its face value.”

He added that a substantial reduction in face value might erode the equity of banks, whose restoration will likely require loans to them at concessional rates and/or a short-term relaxation of the State Bank’s prudential regulations on capital adequacy.

What else can be done?

As suggested by Tabadlab in its report, the government needs to ‘de-risk the business environment’ to attract investors by bringing a stable legal framework to reduce risk. This entails implementing fiscal reforms to address the sovereign’s risk, which is exacerbated by uncontrolled spending and reliance on debt. Demonstrating the capacity for fiscal discipline is essential to lowering overall risk and fostering investor confidence. Similarly, maintaining policy consistency is vital, as investment tends to gravitate towards environments offering higher returns adjusted for risk. Political volatility and fluctuating policy decisions heighten risk levels.

Government discipline through prudent spending, prioritising public investments, and resource efficiency holds the key to mitigating the fiscal deficit. Another frontier is to expand the direct tax net and include retailers and wholesalers in the tax net while simultaneously increasing property taxes.

Analysts at Tabadlab also stress the importance of privatising State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Similarly, expanding public-private partnerships with rigorous governance can help combat inevitable elite rent-seeking behaviour. Doubling down on its efforts, the government should also consider establishing an export-oriented industrial policy, reducing trade barriers, and incentivizing the redirection of credit and capital to local firms to enhance productivity, boost exports, attract increased foreign direct investment, and improve the current account balance.

While all the suggestions from the think tank are valid and supported by sound analysis, implementing even half of them would necessitate a firm and decisive approach from the government. However, in the current political climate where questions persist regarding the clarity of mandates, the feasibility of carrying out such measures seems like a distant prospect.

The country needs serious fiscal reforms.

I agree with your points you have mentioned.