When Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi landed in Islamabad last week, the weight of the world would have been on his shoulders. His country had just ordered missile strikes inside Israel in retaliation for the bombing of Iran’s embassy in Syria by the Israelis.

Pressure and condemnation from the Global North was immediate and powerful. All of this at a time when the Genocide in Gaza has captured global attention. Already a pariah, the Iranian President was arriving in Pakistan at a time when the world’s ire was focused upon him. To make matters worse, Iran and Pakistan had been caught in a tit-for-tat airstrike exchange not four months before the visit.

One could say that the visit was at a tense time.

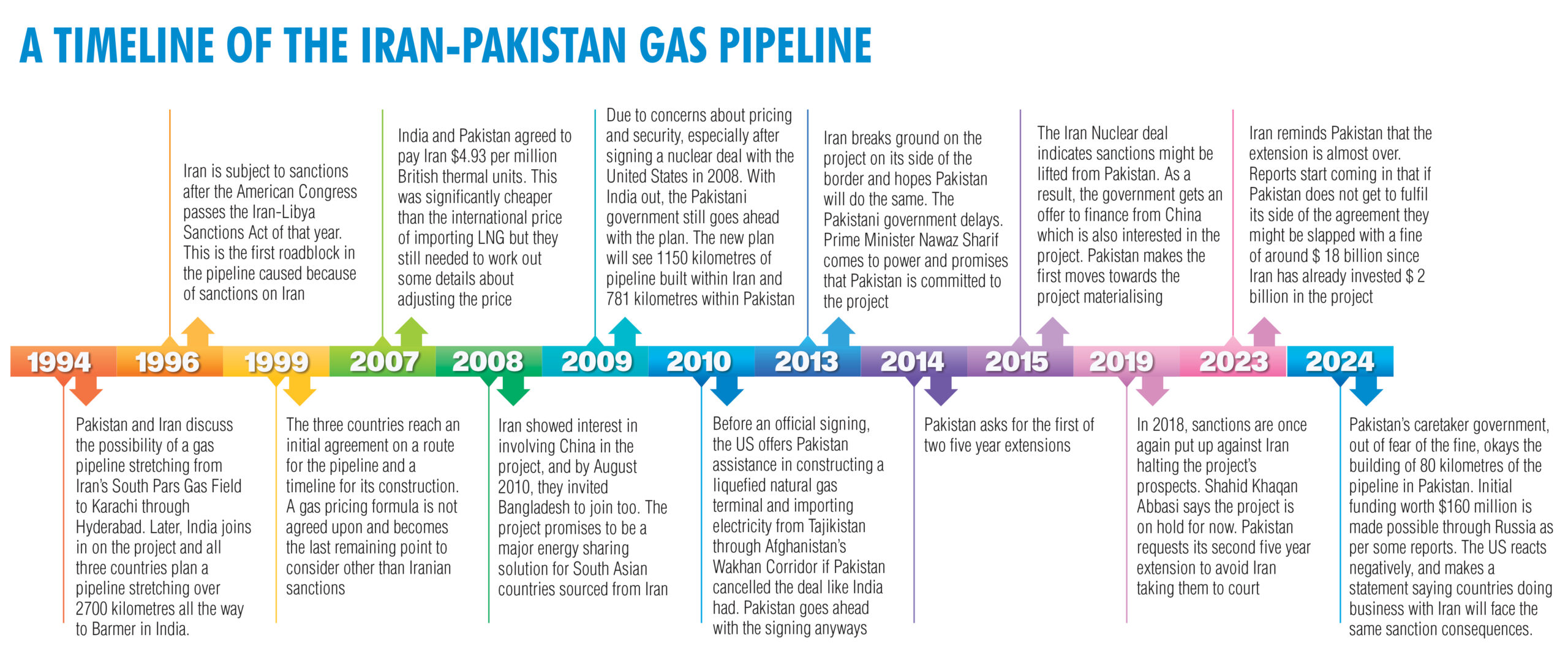

Yet somehow the missiles, the airstrikes, and war in the middle east and Europe were not the most awkward points of conversation between President Raisi and the Pakistani government. That was reserved for the Iran-Pakistan Gas Pipeline project. First proposed in the early 1990s, the pipeline remained a pipedream for the first couple decades. The idea was for a gas pipeline to run from Iran, through Pakistan, and all the way to India. It would give Iran buyers for its vast gas reserves and provided a steady and reliable supply of cheap gas that wouldn’t need to be imported through sea-ports.

Things haven’t quite gone according to plan. India dropped out of the plan in 2009 but Pakistan and Iran went ahead with the deal. Since then Iran has built its side of the pipeline but Pakistan has time and again delayed its participation in the project out of fear of sanctions from the United States. But it isn’t so simple. By not holding up its end of the bargain, Pakistan risks being slapped with a massive fine.

That is the equation that stands before the government of Pakistan. Risk having to pay an international fine or risk the ire of the United States and the economic difficulties of a sanction. So what should the Pakistani government be doing in such a situation? The answer depends entirely on what they plan to do with the gas.

An idea that stayed an idea too long

In the 1990s, Iran was looking for avenues to sell its gas. The sanction-stricken country had by then discovered it had some of the largest natural gas reserves in the entire world. They were able to give cheap rates, but because of international relations, they had no buyers. Normally, there are a few ways to go about exporting natural gas. The preferred method is by liquifying the gas (LNG), transporting it in special vessels across the sea, and unloading it in special floating ports that convert the gas and eventually transport it to pipelines.

But because international markets were unavailable to Iran, the other possibility was to sell to their neighbours. The idea was to set up a gas pipeline that would run from Iran and transport gas from their reserves to Pakistan and possibly onwards towards India. Not only are gas pipelines convenient, they also make transportation significantly cheaper and reduce the cost of the gas. Since building the pipeline is a one time investment, and maintenance is cheaper than one would expect, such a project with neighbours essentially cuts the transport cost out of the equation entirely.

Although these pipelines have associated concerns like inflexibility in delivery points and risk of sabotage, the econom-ics of overland gas pipelines have justified their presence in almost all continents. Existing literature has extensively documented this. The consensus is that natural gas pipelines are economical over shorter distances. When it comes to very large distances, such as over 4000 kilometres, the LNG option has the advantage. For distances under about 3200 kilometres in particular, pipelines are less expensive than LNG, and the network characteristics of pipelines also ensure added reliability and economies of scale for gas pipeline transportation.

A pipeline coming from Iran through Pakistan and all the way to India was perfect for this. The gas would come from the South Pars Gas Field. Easily the largest gas field in the world, ownership of it is shared between Iran and Qatar. To understand the geography of it better, the field actually exists 9800 feet below the seabed — a distance that is one third the size of Mount Everest.

From here the gas would be transported through the South of Iran, run through Balochistan via Gawadar, and then go on to India. But to get the ball rolling, a level of cooperation was required that didn’t exist between the three countries. Many different plans were also made. In 1993, India and Iran discussed a bilateral arrangement to commission a pre-feasibility study in early 1995 for a shallow water offshore pipeline from Iran to India. At the same time, India also explored its options including deep-sea pipelines from Oman and Qatar. However, these did not materialise due to high costs and political hiccups.

The only project that made sense was building a pipeline from Iran through Pakistan to India.

Initial feasibility studies for this showed great potential. The plan for the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline dubbed the “Peace Pipeline” was that Iran would build from its gas field a pipeline 56 inches in diameter over an area of over 1000 kilometres. It would have its offtake point in Hyderabad Pakistan, around 800 kilometres from the Iran-Pakistan border. It would then extend up to Barmer in India, and a further 250 kilometres into the third country. The total length from the South Pars field in Iran to Barmer in India would be around 2700 kilometres, which would make it just the right size to be economically viable.

The hiccups of timing

The only problem was the numerous hurdles. For starters, in 1995 Pakistan refused to grant access for a feasibility study. This was at a time when diplomatic relationships with the Americans were at an all time low and tensions were high with India. Pakistan feared they would support India in a conflict. At the same time, Iran came under sanctions in 1996 when the US Congress passed the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act in response to the Iranian nuclear program and Iranian support for Hezbollah, Hamas.

This meant that only Iran was sanctioned, Pakistan was also going to have a hard time finding financing for the pipeline since international banks and lenders were not going to participate in business with the Iranian regime given the recent sanctions.

Despite this, an initial agreement between the three countries was decided on in 1999. But then the matter stalled for a while and no progress was made.

By February 2007, India and Pakistan agreed to pay Iran $4.93 per million British thermal units. This was significantly cheaper than the international price of importing LNG but they still needed to work out some details about adjusting the price. In April 2008, Iran showed interest in involving China in the project, and by August 2010, they invited Bangladesh to join too.

This was clearly a project they were keen on and wanted to expand.

However, India backed out of the project in 2009 due to concerns about pricing and security, especially after signing a nuclear deal with the United States in 2008. With India out, the Pakistani government under the PPP administration of President Zardari signed an agreement with Iran to build the pipeline anyways between just the two countries.

What followed was Iran enthusiastically jumping on the agreement. The new agreement held that a length of 1150 kilometres within Iran and 781 kilometres within Pakistan was to be implemented by each country in their respective territories. The first gas flow was to start from 1st January 2015. Iran has completed construction of over 900 kilometres within Iran. Meanwhile Pakistan has continued to stall them.

Why has Pakistan been stalling?

The agreement between Pakistan and Iran was signed in 2010. Even as the two countries reached an accord the pressure from the United States was palpable. The US went so far as to offer assistance in constructing a liquefied natural gas terminal and importing electricity from Tajikistan through Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor if Pakistan cancelled the deal like India had.

The Zardari administration went through with the plan. The agreement envisaged the supply of 750 million to a billion cubic feet per day of natural gas for 25 years from Iran’s South Pars gas field to Pakistan to meet Pakistan’s rising energy needs. But over time Pakistan consistently kept stringing Iran along.

For example, while both countries broke ground on the project in 2013, Pakistan did not even acquire the land on which the project was going to be constructed let alone start working on it. In May that year, Iran through official channels wrote a letter to the Pakistani government expressing its concern over the lack of commitment on display. Pakistan, on the other hand, was hesitant to get things started because of the threat of US sanctions. The Zardari administration rode out its tenure and was voted out of power.

In 2013, when the government of Nawaz Sharif came to power, he assured Iran allayed any fears regarding the abandonment of the project and said that the Pakistani government is committed to the fulfilment of the project and targets the first flow of gas from the pipeline in December 2014. The premier also stated that his government is planning to commit to the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline project as well. Still, because of sanctions, it was going to be hard to find financing for the project.

So in 2014, after delaying everything for the time being, Pakistan made it clear that it was being indecisive by asking Iran for a 10 year waiver in breaking ground on the project. There were also reports that Saudi Arabia, a country Pakistan was relying heavily on to manage its debt situation, had expressed its concerns regarding the pipeline being built. And from 2014 up until the beginning of this year that was that. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, then the petroleum minister, said in parliament that sanctions meant the project was being hit with delays.

Some hope was revived in 2016 when sanctions were lifted on Iran and the then President Rouhani visited Pakistan, where the gas pipeline was under discussion between him and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. With the sanctions gone, Pakistan decided to go ahead with the project after securing funding from Chinese institutions. China was providing 85% of the total financing for the LNG pipeline project and wanted to emulate the same model for building the remaining portion of the pipeline from Gwadar up to the Iranian border.

But by 2016, the Iran Nuclear Peace Deal seemed destined to be doomed. Brokered by US President Obama, his successor Donald Trump took the US out of the deal by 2018 and reimposed sanctions on the country. Pressure was once again exerted on countries doing business with Iran and the pipeline project was once again under scrutiny and came to a halt. At the time, there was also a great lack of political will. Nawaz Sharif had been ousted, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi had seen a brief premiership, and Imran Khan had just come to power. It was now the new PTI government which would continue or stall work on the project.

What they did instead was follow the same will-they-won’t-they attitude that the previous governments of the PPP and PML-N had adopted. In 2019, Pakistan urged Iran to explain in-writing its interpretation of sanctions that resulted in a massive delay in completion of the mega Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. The problem was Pakistan could not abandon the project at this point.

Tehran says it has already invested $2 billion to construct the pipeline on its side of the border, making it ready to export. – Pakistan, however, did not begin construction and shortly after the deal said the project was off the table for the time being, citing international sanctions on Iran as the reason. The 10-year extension Pakistan had asked for in 2014 ended in January 2024, and Iran was once again knocking at Islamabad’s door. Reports started coming in that if Iran took Pakistan to international arbitration court, the country could be fined up to $18 billion for not holding up its half of the agreement.

The potential of the fine set things straight. A meeting of the Cabinet in February finally approved the construction of the first 80 kilometres of the Pakistani side’s pipeline to avoid the fine. Reports started coming in that Russia was providing funds for this initial construction which would cost Pakistan somewhere around $160 million. But the response from the United States has not been favourable, and the US has threatened consequences in the shape of sanctions.

The state of electricity in Pakistan

The only question that really matters is just how badly Pakistan needs this gas. The answer lies in how the government intends on using this gas. If the purpose is to provide cheap gas to households for domestic consumption then the rewards for taking on the risk of US sanctions is quite high. But if the purpose is to generate electricity, provide it to industrial customers, produce goods and decrease Pakistan’s import bill then it might make sense.

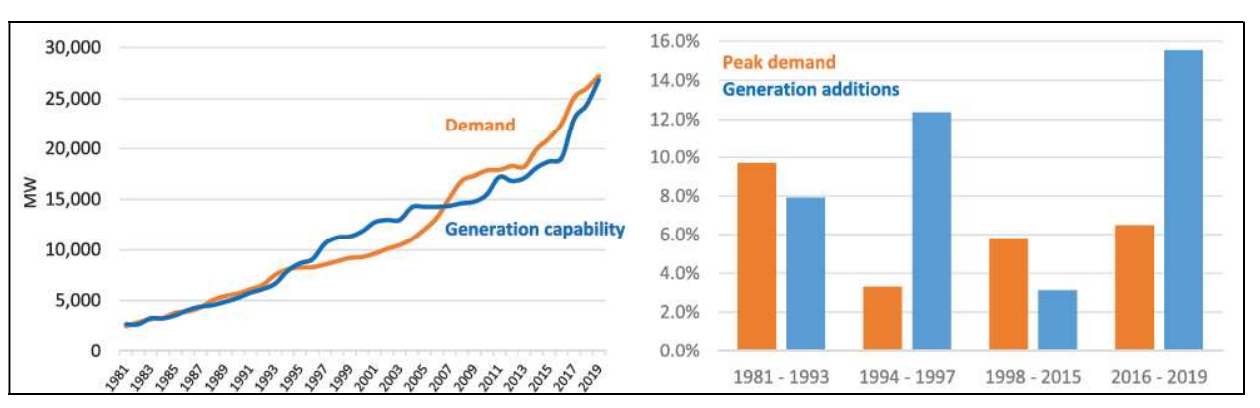

In the early 1990s, it wasn’t quite apparent that Pakistan was heading down a path that would lead to an energy crisis. At the time, a majority of the country’s electricity generation was coming from hydroelectric power through the Mangla and Tarbela dams. But the government was also on an expansionary path.

The problem for Pakistan was finding a source of energy that could be used to make cheap electricity that could then be used by commercial and domestic consumers.

In the 1980s, the government of Pakistan did start setting up oil-fired power plants.

At that point, with international financing difficult to procure owing to Pakistan’s poor relations with the United States, the government instituted a policy that allowed for more private sector players to set up independent power plants (IPPs) that were reliant mainly on oil. Over the next decade, this increased Pakistan’s reliance on imported oil as a fuel for its electricity generation.

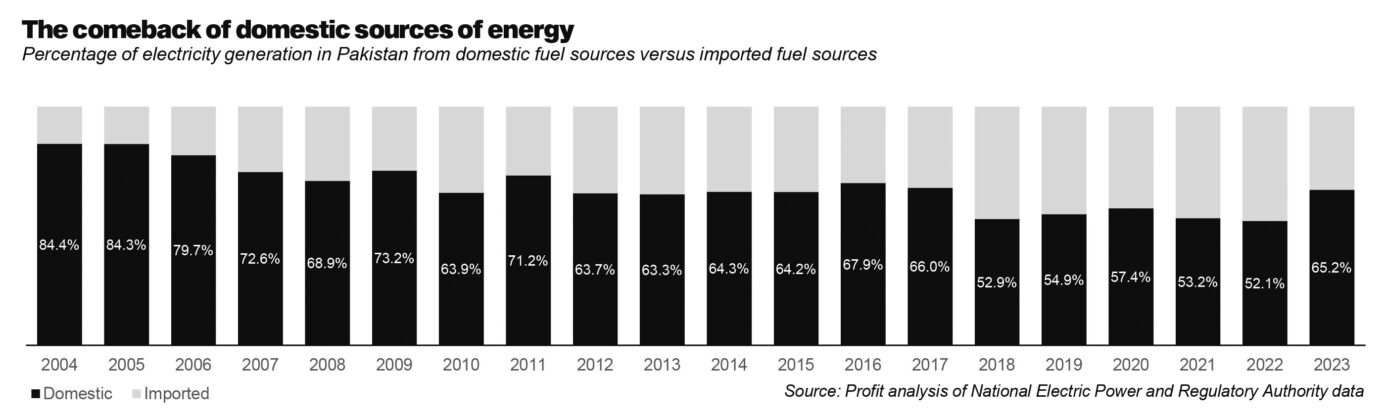

In the early 2000s, the Musharraf Administration decided to convert at least some of that thermal power generation capacity from imported oil to domestic natural gas, under the assumption that Pakistan had abundant domestic reserves. This assumption was wrong and it didn’t require great foresight to know that it was wrong. As early as 1995, the government of Pakistan had access to estimates that suggested that Pakistan’s natural gas production was predicted to peak in 2010 and precipitously fall thereafter.

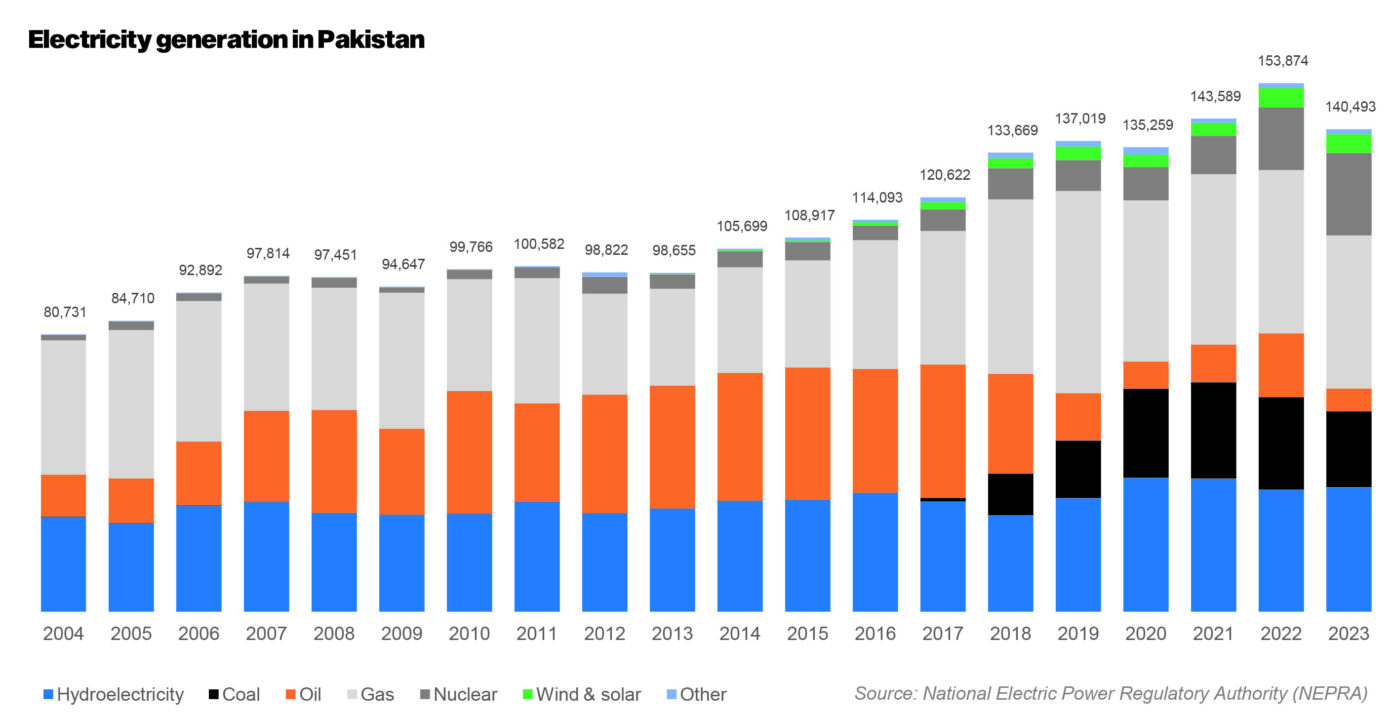

It was the Nawaz Administration in 2013 that pursued a solution to part of the problem, and actively sought to commercialise power generation in Thar, replace the waning domestic natural gas with imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Qatar, and above all, incentivize the private sector to build lots and lots of thermal power plants, while simultaneously embarking on a massive government spending spree on increasing hydroelectric power generation. Those policies are now bearing fruit, and after nearly a decade and a half of almost consistent decline, the domestic share of primary fuels for electricity generation in Pakistan rose substantially in fiscal year 2023, and may continue to rise in the coming few years.

Over the past 10 years – since the Nawaz Administration began dramatically altering Pakistan’s electricity generation mix – the country has increased its power generation output by 42%, from 98,655 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in fiscal year 2013 to approximately 140,493 GWh in fiscal year 2023. The aggregate increase, however, is not the full story. During that time, imported LNG replaced imported oil, and imported coal replaced the decline in natural gas. And when we say replace, we mean that almost literally. Between 2013 and 2023, electricity generation from oil-fired power plants declined by 29,162 GWh, and that generated by LNG-fired power plants went up by 29,282 GWh, an almost exact one-to-one replacement. Power plants run on domestic natural gas saw production decline by 12,942 GWh and replaced almost exactly by an increase of 12,457 GWh in imported coal-fired power production.

Now, the addition of cheap Iranian gas into this mix would not just increase power generation capacity but also provide a cheaper energy mix. The only trouble is that Pakistan has managed to find alternative sources for this energy at home. While Iranian gas might have been a game changer in 2014, the past nine years have not been quite bad. For starters there is Thar Coal. From 2013 to 2023 power plants run on domestic natural gas saw production decline by 12,942 GWh and replaced almost exactly by an increase of 12,457 GWh in imported coal-fired power production (which itself is now being replaced at least partially by Thar coal).

Then there is nuclear energy. As recently as 2009, Pakistan got less than 2% of its electricity from nuclear energy and now that number is above 17% of the total electricity generated in the country, largely on the back of Chinese-backed nuclear power plants at Chashma, and a substantial increase in the generation capacity at the nuclear power plant in Karachi. So important is nuclear to Pakistan’s increase in electricity generation that the net amount of nuclear energy added to the grid is about equal to the total added by Thar coal, wind, and the new hydroelectric power plants combined.

This means that while gas from Iran could be used to bolster Pakistan’s electricity production, the country has found other ways to do this. As such, it is not so important that Pakistan should risk its ties with the United States for, particularly at a time when Pakistan is dependent on the IMF and others to fulfil its external debt obligations.

Natural gas supply

But the importance of cheap gas cannot quite be understated. Just look at the crisis that has been ongoing in Pakistan’s gas sector since the start of the year on the instruction of the IMF.

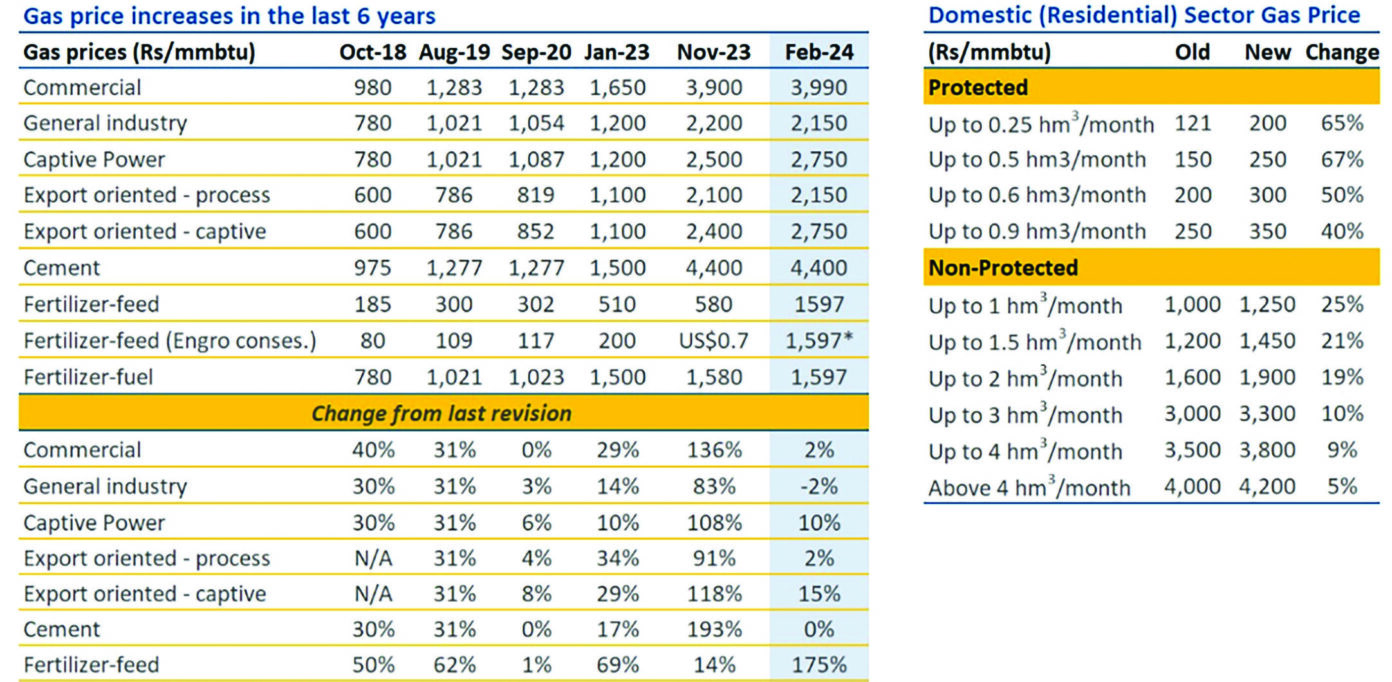

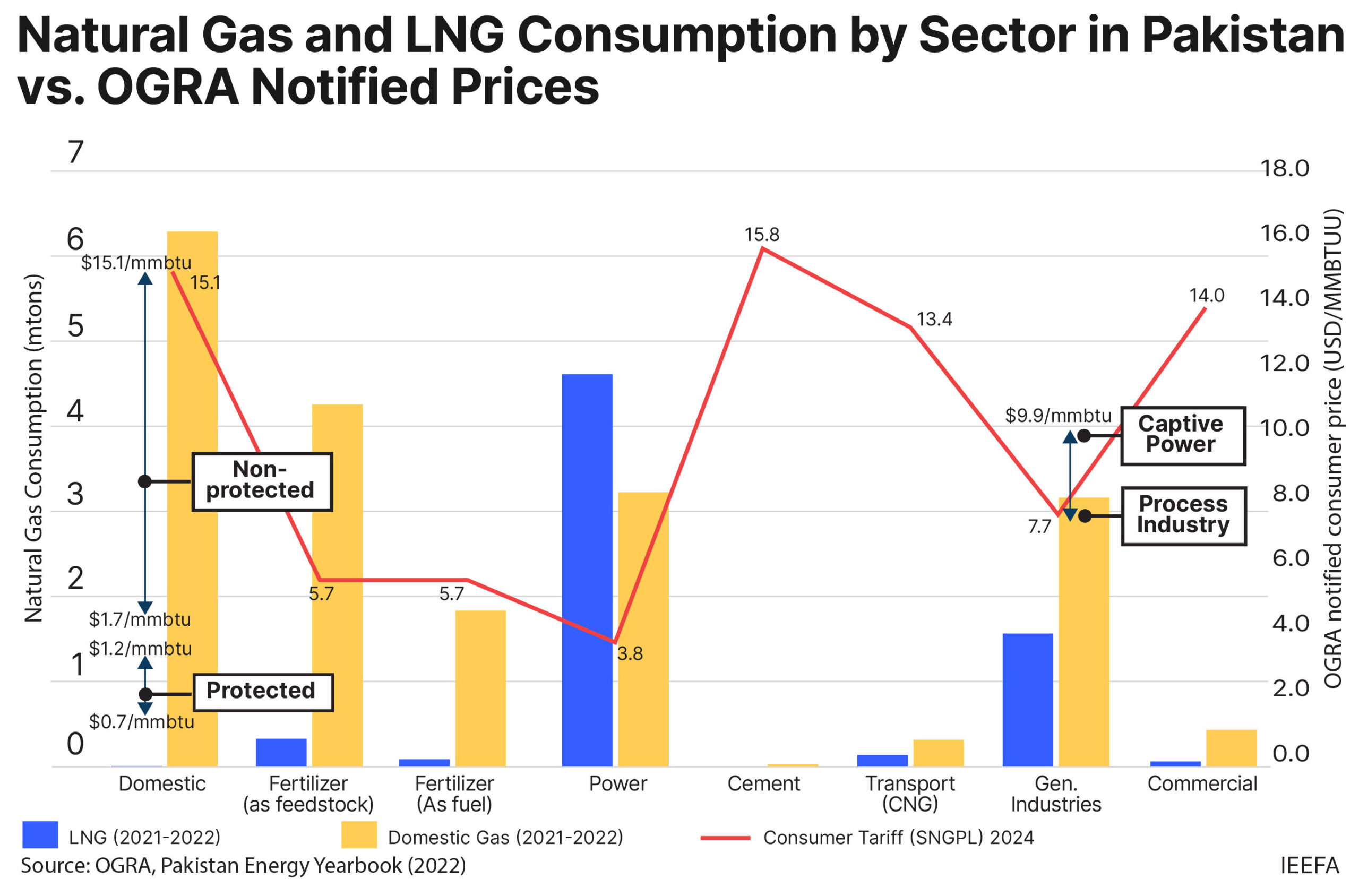

There is a reason the IMF wants to increase gas prices in Pakistan. Very briefly put, Pakistan does not have a lot of gas but we use it like we do. The IMF, as part of the ongoing programme, wanted to increase the price of gas for all domestic and commercial consumers. You see, Pakistanis have gas cross subsidised. This means that the natural gas we produce is given to different consumers at different rates. There is one category of protected consumers which get it at the cheapest possible rate. These are small domestic consumers that use gas below a certain amount and tandoors that make rotis. Even within this protected category there are slabs and everyone is charged differently based on how much they consume. Essentially, bigger consumers end up subsidising smaller consumers.

And while this is a people friendly policy and popular for political decision makers, it is also unproductive. Because we don’t have a lot of gas available, the IMF and other bodies such as the World Bank have always felt that gas should be used by industries for productive purposes rather than by domestic consumers to power stoves and heat water. This particularly becomes a problem in the winters, when the domestic need for gas increases, governments end up cutting it to industrial users. The gas industry circular debt is a relatively new situation caused by rising LNG costs and delays by the government in announcing the new and higher tariff consistent with the international gas price hikes. Another contributing factor is the government’s inefficient utilisation of this commodity coupled with untargeted subsidies.

The fundamental cause of the circular debt is the unpaid government subsidies intended for residential and export-oriented consumers for the consumption of LNG. This has hampered Sui Northern Gas Pipelines (SNGPL) and Sui Southern Gas Company’s cash flows (SSGC) as they are not able to recover the actual cost of importing LNG from their respective customers. To make the point clear, LNG costs a lot more than domestically produced gas, therefore naturally the price should be set at a level that would allow the recovery of the costs. But that is not the case as the government diverted the expensive LNG to domestic consumers which cannot afford to pay for it. This has resulted in ballooning receivables from the twin gas distributors on the balance sheets of energy exploration corporations, primarily the Oil and Gas Development Company (OGDC) and Pakistan Petroleum Ltd (PPL). To summarise it, the government has not paid up the subsidy amount it owes to SNGPL and SSGC for providing gas at lower rates than what it actually costs. The debt is parked within other state owned enterprises, as is the common practice of the government.

Because of this, the IMF ideally wants gas to come to its original price instead of being cross subsidised, which might result in domestic consumers in particular switching to electricity. In fact, one of the most ideal scenarios for the IMF and indeed for industrial consumers is that domestic consumers switch from using gas to cook their food and heat their water to using electricity. The only problem is that domestic consumers are used to cheap gas. Electric cooking ranges, for example, are a rarity in Pakistan. Similarly electric geysers and water heating systems have simply not developed. This is despite the fact that at their real prices, and particularly with solar solutions, electricity is much cheaper than gas. The gas price hikes reflect this. Just take a look at how the prices have increased. Domestic protected consumers and tandoors have had their rates hiked by up to 70% in some cases. Similarly the non-protected category has seen an increase in prices of up to around 25%. But the real shift is in the subsidies that were being provided to industrial consumers.

The first round of gas price increase took place back in November 2023. Back then commercial connection rates were raised by 136%, and the biggest increase was in the cement sector which saw a hike of around 193%. The fertiliser industry was still protected, however. This particular price hike has been gentler on these sectors and has instead focused on the fertiliser industry which has seen an increase of 175% in gas prices.

A big part of why these changes were implemented were the constant insistence of successive governments to provide gas to domestic users at cheap rates. If the government intends on importing gas from Iran for this purpose, then it would be folly. However, if the government can ensure that every unit of gas coming from Iran would be used for its most productive purpose then it might be worth it. The gas could be provided to captive power plants, to the fertiliser sector without subsidies and could help ease inflationary pressures.

Furthermore, there is the issue of supply security. While LNG prices are anticipated to decrease in the future with an influx of supply expected after 2025, Pakistan may still face challenges competing with larger consumer nations for this surplus supply. This competition may result in Pakistan continuing to pay elevated prices due to oil-indexed contracts and high credit risk.

This scenario unfolded in 2020 when LNG spot prices plummeted as a result of the economic repercussions of COVID-19. Despite the market conditions, Pakistan honoured its long-term supply agreements and paid a premium price. Locking in additional supply under the same conditions may impose a financial burden on consumers that could be unsustainable.

Going the waver route

So what exactly does Pakistan do in this situation? On the one hand there is the risk of sanctions. On the other hand Pakistan could be slapped with a massive fine twice the size of its foreign exchange reserves. The first step, which even the government of Pakistan is not incompetent enough to not to take, is attempting to ask the US for a special waiver.

Back in March when they started work on the project, the US immediately expressed its displeasure. Last month, Donald Lu, the US assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asia cautioned Pakistan against importing gas from Iran, as it would expose it to US sanctions.

In response, Pakistan’s Foreign Office spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch made a case for national sovereignty; since the pipeline is being built within Pakistani territory, “we do not believe that at this point there is room for any discussion or waiver from a third party”, she said. Nonetheless, Thomas Montgomery — the acting US mission spokesperson in Pakistan — offered the following words of caution: “We advise anyone considering business deals with Iran to be aware of the potential risk of sanctions.” The US has been pushing Pakistan to seek green alternatives; through its development agency it has helped add almost 4,000 MW of clean energy to Pakistan’s grid since 2010.

The government also said they would seek a U.S. sanctions waiver for the pipeline. However, later that week, the U.S. said publicly it did not support the project and cautioned about the risk of sanctions in doing business with Tehran. And as reported in the international media, “Washington’s support is crucial for Pakistan as the country looks to sign a new longer term bailout program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in coming weeks. Pakistan, whose domestic and industrial users rely on natural gas for heating and energy needs, is in dire need for cheap gas with its own reserves dwindling fast and LNG deals making supplies expensive amidst already high inflation.”

The choice ahead

Pakistan must choose carefully what it does from this point on. There are many benefits to going ahead with the Iran gas pipeline project. The gas can help in electricity generation and can also be a major source of relief for export oriented industries. The goal, however, must be to ensure that it is used in the most productive and efficient manner possible.

Because if different governments start providing cheap gas to domestic consumers as a publicity gimmick there will be very little point to risking sanctions from the United States. It is a path Pakistan has gone down before and it does not end in a pretty destination.

The matter from this point onwards needs to be handled diplomatically. Iran has shown great patience over the past two decades and has persisted with the pipeline project. They have done so because they have to, but policymakers would do well to remember that it is looking like Tehran is running out of patience. If they choose to go to international court, Pakistan will be staring down a very steep penalty. The best bet is to get the United States on board, but the timing is particularly bad because of the war in the middle east and condemnation of Iran coming from America and its allies.

Up until now, Pakistan has tried to maintain a balance. President Raisi received a very warm welcome from Islamabad but the issue of the pipeline remained one talked about in hushed tones and no formal statement was made. One can assume that this means no decisions have been made up until now. But if the economic benefit is in building the pipeline, Pakistan should not fear US sanctions and needs to instead present its case diplomatically and lobby for an exemption from sanctions. Ideally the case for building the pipeline should be presented by India and Pakistan together, but it is unlikely that prevailing diplomatic tensions will allow that. In the absence of this joint strategy, Pakistan’s diplomatic corp have some brainstorming to do.

Excellent. Wow. Great research.