The landscape of microfinance banking in Pakistan is a complex one, combining both skepticism and optimism. The sector faces challenges due to its exposure to economic shocks that can impact low-income borrowers. It is essential to carefully analyze the vulnerabilities of institutions operating in this segment.

Nevertheless, the pivotal role of the microfinance banking sector in providing financial services to underserved populations in Pakistan is a notable accomplishment. This underscores the critical importance of microfinance in promoting financial inclusion and economic empowerment within the country’s most vulnerable communities.

Microfinance banking in Pakistan dates back to the inception of Khushali Bank in 2000, which was established under a special ordinance. The subsequent MFI Ordinance of 2001 laid the regulatory foundation for microfinance institutions, with a specific focus on providing financial support to micro-enterprises and marginalized individuals as part of a sustainable poverty alleviation strategy.

What sets MFIs apart from traditional commercial banks is their unique approach to lending. They provide a substantial portion of their financing without collateral, catering to various economic activities, including housing.

This model allows them to serve clients who might otherwise be excluded from formal financial systems. MFIs typically deal in smaller loan amounts compared to commercial banks, with general loans capped at Rs. 350,000 and housing loans limited to Rs. 3 million.

But, the sector has had its own share of troubles over the past few years and there is no respite in sight.

The state of play

Currently, there are 12 Microfinance Banks (MFBs) in the country, with HBL Microfinance Bank, UBank, and Khushali Bank being the largest in terms of lending book size. The industry’s prominent sponsors include commercial banks, NGOs, and telecom operators, reflecting a diverse range of stakeholders.

MFBs have demonstrated significant progress over the past five years. The asset base of MFBs has shown robust growth, with an average year-on-year growth of 19.1%. Equally impressive is the substantial increase in the gross loan portfolio, which has doubled from Rs. 214 billion in December 2019 to Rs. 427 billion in December 2023.

This growth is not just financial; it’s also reflected in the sector’s expanding reach. The number of active borrowers has increased significantly, rising from 3.6 million to 6.3 million during the same period.

But, there is more to it

Though the expansion numbers might seem impressive, there’s a significant caveat: MFBs have recorded losses for the fifth consecutive year in 2023. While this might surprise those unfamiliar with the segment, industry observers are well aware of its inherent vulnerabilities.

Remember the unique characteristics that set microfinance operators apart from commercial banks? It seems this very uniqueness is now pushing the sector into troubled waters. At the core of MFBs’ business model is unsecured lending – money lent without collateral, relying solely on personal guarantees and expectations of borrowers’ future cash flows. Currently, it constitutes more than 50% of the sector’s lending.

This model functioned relatively well until 2020 when the pandemic unleashed economic chaos. The situation worsened with the catastrophic floods of 2022, which dealt a severe blow to the agri sector – the primary borrower base for MFBs. Consequently, banks had to restructure loans twice: first in 2020 and again in 2022. The recoverability of these loans remains questionable, and as MFBs provide for potential losses in their financials, it has pushed earnings into negative territory.

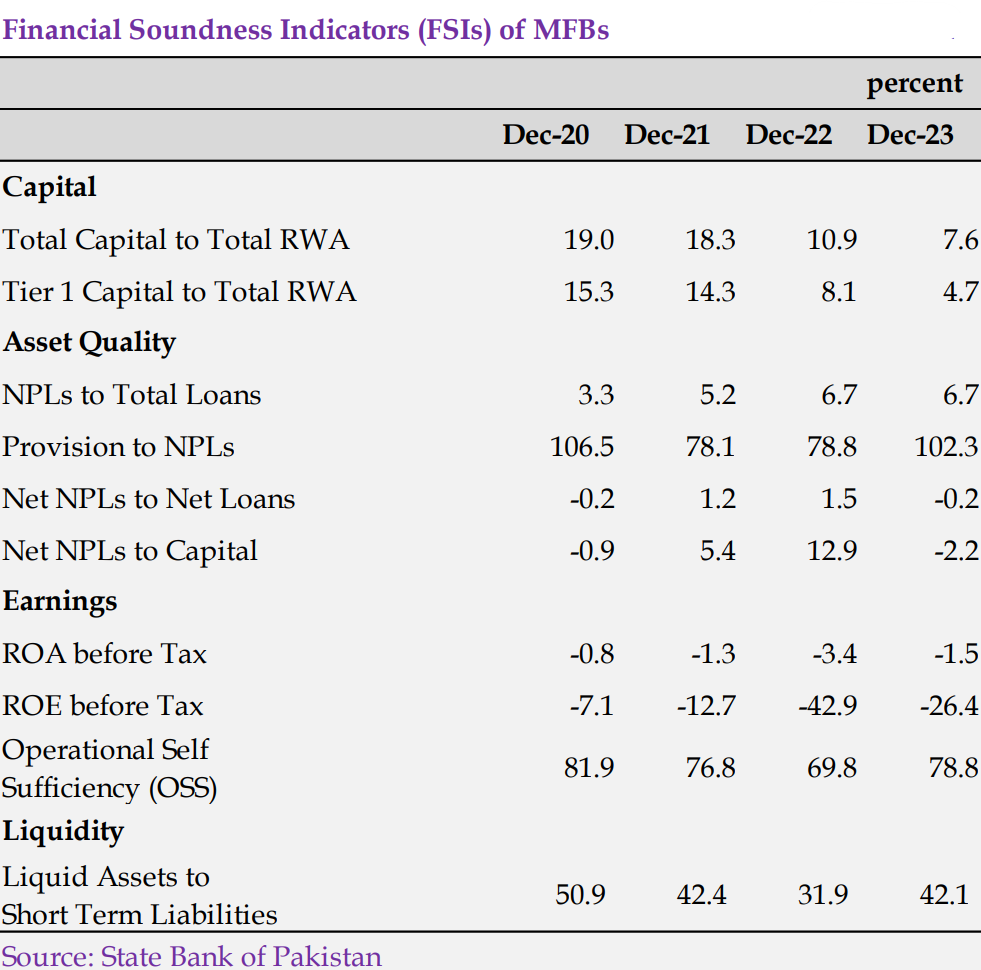

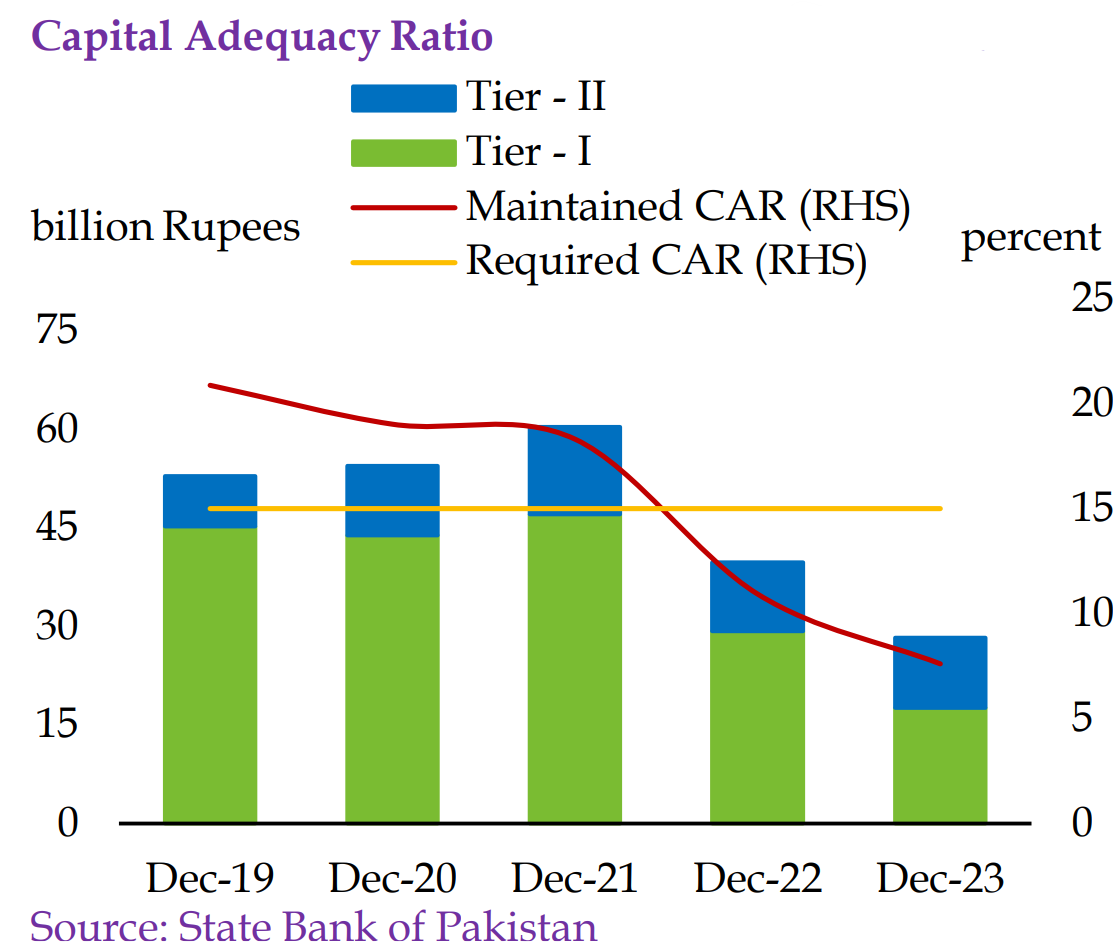

This financial strain has taken a toll on the MFBs’ capital base. Unsurprisingly, the sector as a whole is now undercapitalized, with a Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) of 7.6% – almost half of the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) regulatory limit of 15%.

Adding to these concerns, both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have flagged vulnerabilities in the segment. The IMF went so far as to block the government from extending deposit protection insurance to MFB customers. Their rationale? Undercapitalized banks in the sector pose a real risk of failure, which could result in a significant fiscal hit for the government if such insurance were extended.

Who’s sick? The business model!

Who’s sick? The business model!

While it’s true that not all MFBs are undercapitalized, it is the conventional business model of MFBs that is struggling in Pakistan. As of the end of 2023, several major players – Khushali, Ubank, NRSP, FINCA, and APNA – remained undercapitalized, highlighting the widespread nature of the challenge.

The MFBs that have maintained relatively better capitalization fall into two main categories. First are the telecom-backed institutions like Mobilink Bank and Telenor Bank.

These have shifted their focus away from conventional microfinance banking to digital financial services products such as Jazzcash and Easypaisa, leveraging their parent companies’ technological infrastructure and customer base.

The second category comprises provincial or district-level banks with significantly smaller lending books.

HBL Microfinance Bank stands as a notable exception to these two categories. The MFB barely met the capitalization threshold with a CAR of 15.3% at the end of 2023. However, this comes at a cost. The bank has required almost Rs. 10 billion in equity injection over the past four years, including a recent announcement of Rs. 6 billion. To put this in perspective, Rs. 10 billion is the amount required to set up an entirely new commercial bank in Pakistan.

So where are we going with this?

Before delving into potential outcomes, it’s crucial to reiterate the importance of the microfinance sector. Despite representing only 1.3% of financial sector assets, these banks serve over 70% of all borrowers in the financial sector and account for approximately a third of all outstanding agriculture loans.

Now, turning to the troubled players in the sector, different strategies are emerging. For some, equity injections are likely to continue. Take Ubank, for instance. Its CAR further declined to 9.4% in the first quarter of 2024.

Subsequently, its board approved the conversion of its sponsor’s (PTCL) preference shares into ordinary share capital of Rs. 1 billion, and subordinated debt of Rs. 1.2 billion was also converted into ordinary share capital. Additionally, there was a cash equity injection of Rs. 1.2 billion.

For banks like NRSP and Khushali, which carry negative equity, the road to recovery appears longer and more challenging.

NRSP, for example, obtained in-principle approval from shareholders last year for the issuance of rights shares amounting to Rs. 3.5 billion. Of this amount, Rs. 1 billion has already been injected through advances against the bank’s rights issue. However, the issuance of the remaining Rs. 2.5 billion remains uncertain.

While Khushali Bank’s Board of Directors has approved two major plans to address recent losses: the Long-Term Strategic Plan 2024-2030 and the Self-sustaining Restructuring Plan 2024-2030.

The Long-Term Strategic Plan aims to boost growth and profitability of the Bank with Rs. 8 billion in capital injections. The Self-sustaining Restructuring Plan serves as a backup strategy in case new capital cannot be secured. The Bank is currently raising fresh capital from existing shareholders through a right issue.

For smaller players, it seems like the end of the road. Egypt-based fintech MNT-Halan has already acquired Advans Microfinance. While not officially confirmed, MNT-Halan is likely to leverage Advans’ license and operational infrastructure to enter Pakistan’s digital financial services market, rather than expanding microfinance operations.

Meanwhile, another fintech company ABHI, in partnership with TPL Corporation, is considering the acquisition of FINCA Bank.

Could it have been any better?

Looking back, it’s easy to spot where things went wrong. What really jumps out is how fast MFBs were growing. Sure, they were following the SBP’s push for financial inclusion, but they seemed to forget about the “sustainably” part of that directive.

Now it’s pretty clear that this growth was kind of reckless. These banks didn’t have solid risk management in place and were handing out loans left and right without much thought. When two major crises hit within just two years, it really exposed how shaky their foundation was.