Some time within the next two years – and quite possibly by the end of this year – something extraordinary will happen in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry: the largest pharmaceutical company by revenue will be a local one, rather than the subsidiary of a foreign multinational corporation. This may be the first time in Pakistani history that this has happened.

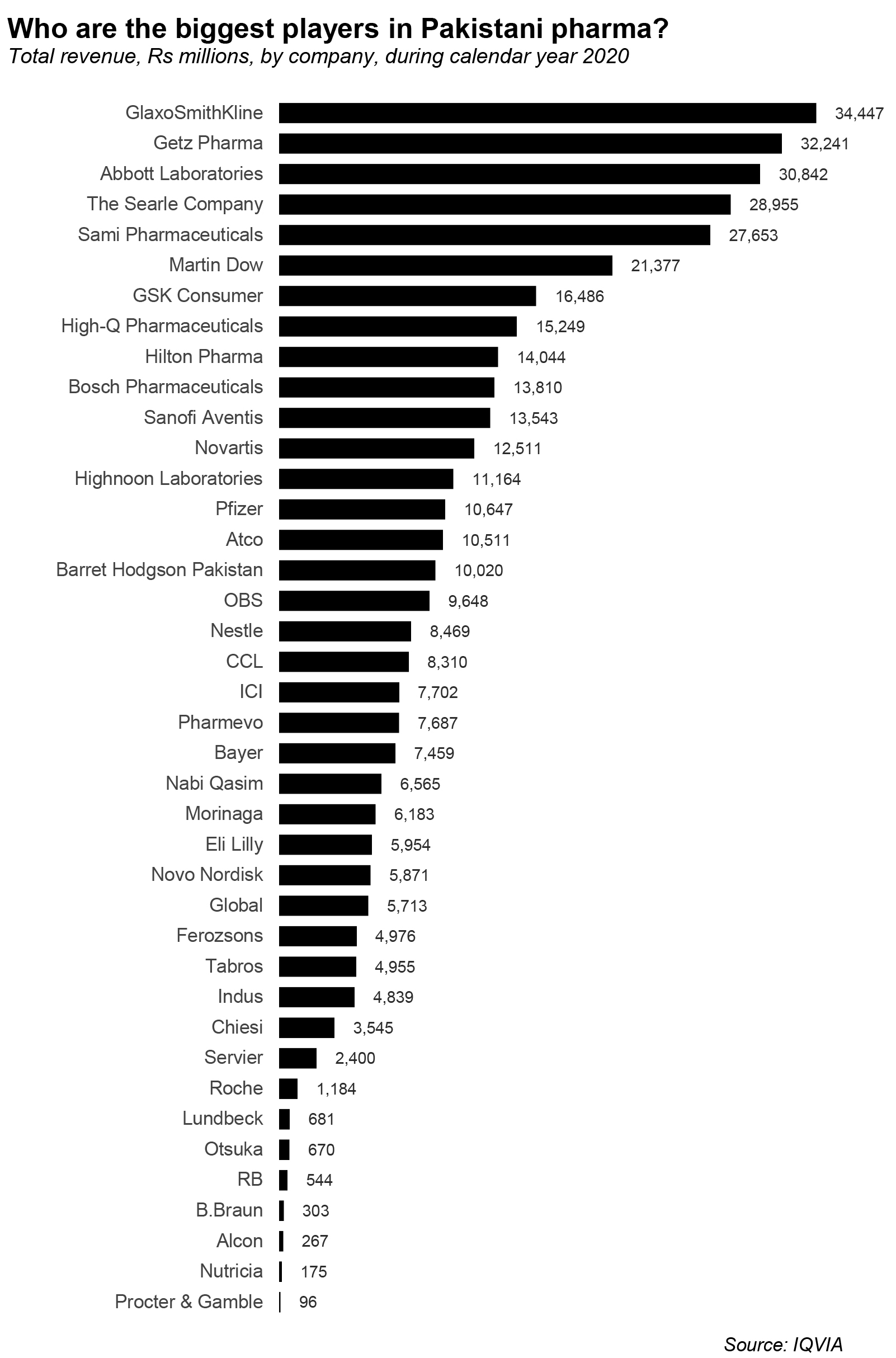

As of the end of calendar year 2020, the largest pharmaceutical company in Pakistan is GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan, the local subsidiary of the UK-based global giant, with Rs34.4 billion in local revenues. The second largest is Getz Pharma, owned and operated by CEO Khalid Mahmood, is a local company that manufactures mostly generic drugs, with Rs32.2 billion in local revenue, according to data from IQVIA, the global pharmaceutical data provider.

While GSK is currently bigger than Getz, the latter is growing significantly faster, with 2020 revenue growth numbers clocking in at 6.4% for GSK and 14.0% for Getz. In other words, the local company is rapidly gaining on the global giant and may soon overtake it in aggregate local market share. (The global parent of GSK will likely remain the largest player overall in Pakistan, owing to the fact that it operates a second subsidiary in the country called GSK Consumer Health.)

This story, however, is not about Getz versus GSK. It is about the broader trend that is taking place in Pakistan where the local pharmaceutical industry is growing faster than their foreign counterparts operating in the Pakistani market. This is despite the fact that the foreign pharmaceutical giants that have Pakistani subsidiaries have – at least in theory – access to far more innovative and new products than the largely generic products sold by the local companies.

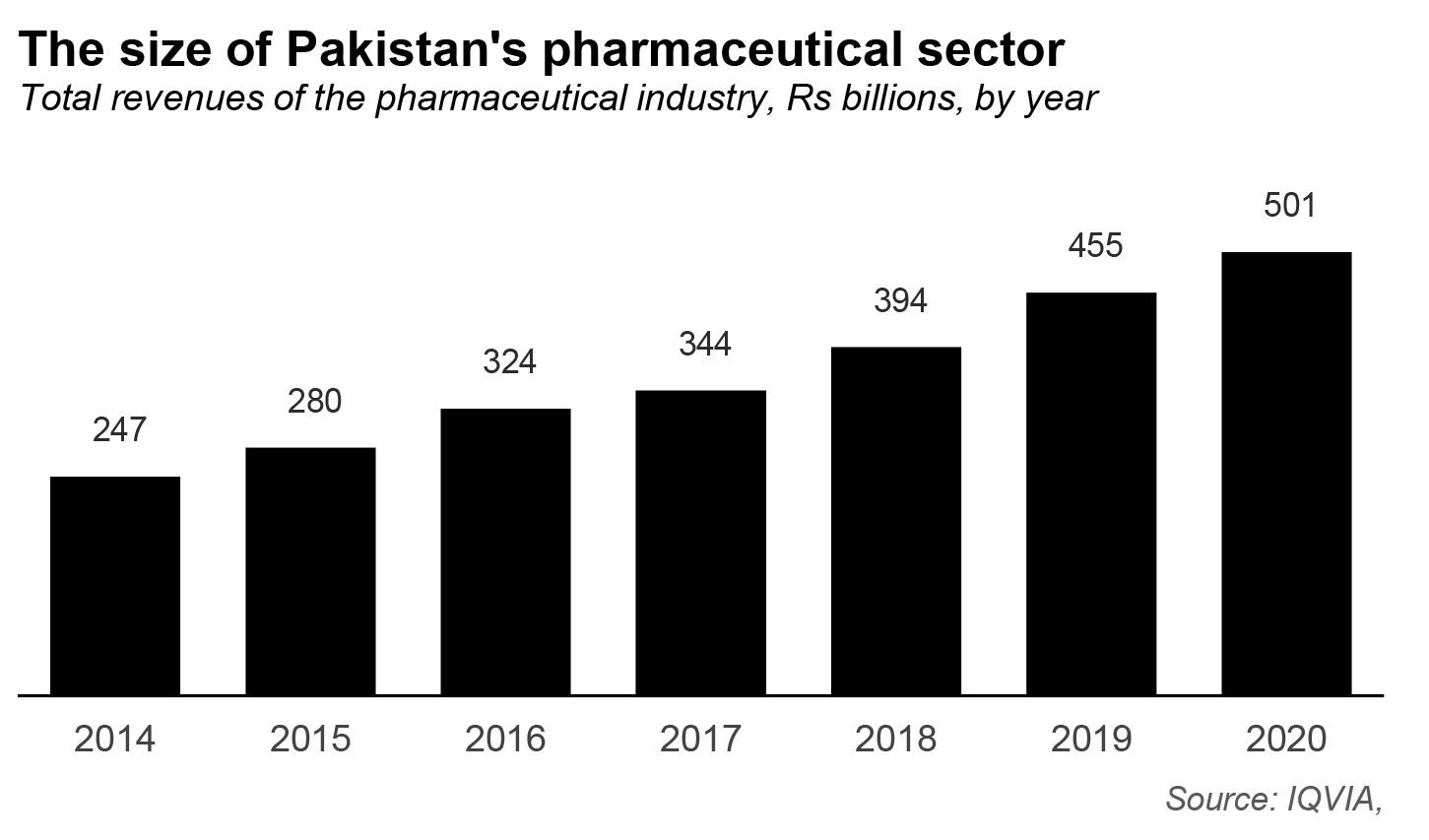

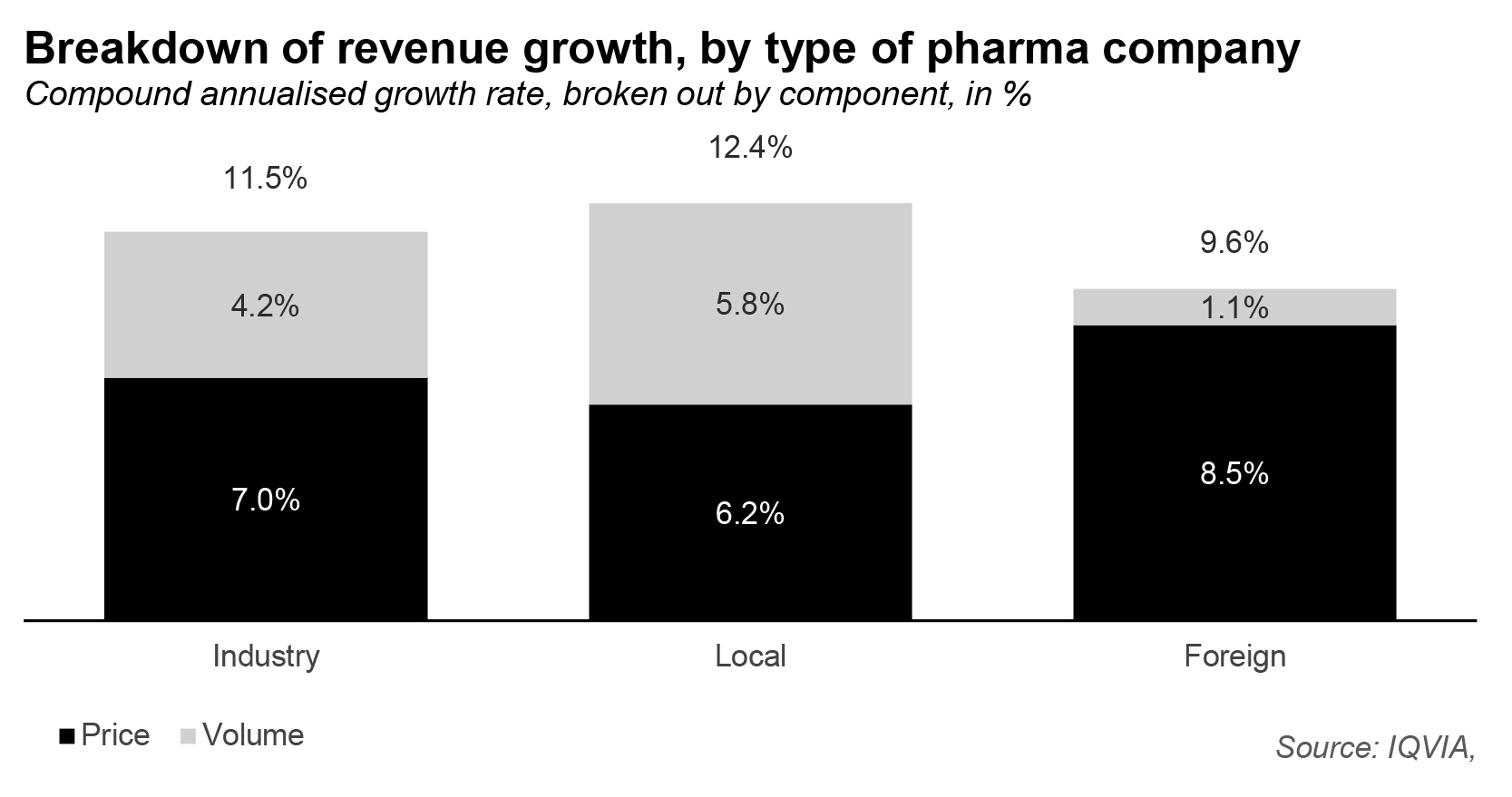

But the data tells an unmistakable story: if you bifurcate the Pakistani pharmaceutical industry into local versus foreign players (as IQVIA does in its data sets), one gets a very clear picture: between 2016 and 2020, the aggregate industry grew its revenues by an average of 11.5% per year to reach Rs501 billion for the financial year ending December 31, 2020. But during that period, the local industry averaged 12.4% growth per year, whereas the foreign companies averaged 9.6% per year.

How have the local companies done this? What are they able to navigate better than the foreign companies? And how stable is the advantage of the local companies? But first, a brief introduction to the industry in Pakistan.

Industry structure

There are 775 pharmaceutical manufacturers in the country. However, of those, the top 15 have an approximately 59% combined market share and the top 100 command close to a 97% share of the total revenue of the industry.

In terms of market share, the local companies have about 68.8% of the industry’s revenues, whereas the foreign companies have approximately 31.2%. That is down slightly from the 33.3% that they used to command in 2016.

While the largest pharmaceutical company in Pakistan is GlaxoSmithKline, the country also has a local presence of some of the biggest names in pharmaceuticals: Abbott, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, Novartis, etc. all have a presence in Pakistan, and often quite substantial ones at that.

The local companies include names like Getz Pharma, The Searle Company, Martin Dow, Hilton Pharma, etc. The overwhelming majority of these, even the largest ones, are generic drug manufacturers with very little by way of local research and development capabilities, though some of these companies do participate in global drug trials for products developed by global pharmaceutical giants.

The drug pricing problem

The single most important thing to understand about the pharmaceutical industry is the fact that the government sets its prices, and decides how much they can increase their prices by each year. The entire pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan is regulated by the government under a legislative framework first created by the 1966 Drug Act, which also created the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP).

DRAP has introduced pricing policies first in 2015 and then in 2018 that were designed to ensure that pharmaceutical companies are able to continue to make profits on their products while also not increasing the prices too much for the public. Coming as it did after a 15-year effective moratorium on drug price increases, that change was considered welcome by the industry.

But the structural problem is this: the government sets both the retail price as well as the retailers’ margins, which effectively means that gross profit margins for the entire industry are set by regulatory fiat. The manufacturer is able to receive a price between 20% and 25% below the retail price, which means that the entire supply chain operates on margins contained in that 25% margin.

This gets us into an age-old debate when it comes to drug prices. Pharmaceutical companies argue that they need both patent protection for the newly researched drugs that they have produced, as well as the ability to charge whatever prices they deem fit in order to be able to cover the cost of the research and development that goes into producing new and innovative therapies.

Critics of the pharmaceutical industry – at least the ones that know what they are talking about – that pharmaceutical products are not like other products where a consumer has many other choices, including the ability to choose not to buy the product. A life-saving product is something that the person who needs it values very highly and would be willing to pay even extortionate levels of prices to secure access to something that will keep them alive. But it is in society’s interest that as many people as possible have access to the healthcare products they need, and hence they advocate for price controls.

The approach advocated by the pharmaceutical companies is one adopted pretty much only by the United States. Virtually every other country in the world has some form of price controls over and above any public health insurance program they may have. That means that most countries not only offer free or highly subsidized healthcare to their citizens, they also force the pharmaceutical companies to charge prices determined by government bureaucrats, and not the market.

In effect, this means that the large multinational pharmaceutical companies – whether they be American or European – make their money in the United States to help pay for the research and development activities they conduct for breakthrough therapies. The United States is subsidizing the development of advanced treatment for the whole world.

(That, by the way, is why the US government did not even blink before making sure that the US had adequate vaccine supplies first, before then allowing them to be shipped to other parts of the world. If they pay for the development, they feel like they deserve access before anyone else.)

Why is all of this relevant to the Pakistani pharmaceutical sector? Because it illustrates the kind of market environment the multinational companies face globally, and it affects the choices they make locally.

Pakistan is like almost every other country in the world in that it has government-mandated price controls for pharmaceutical products. And the government not only mandates the initial price, it mandates just how much they can go up each year, and how much each participant in the supply chain is allowed to keep as their profit margin.

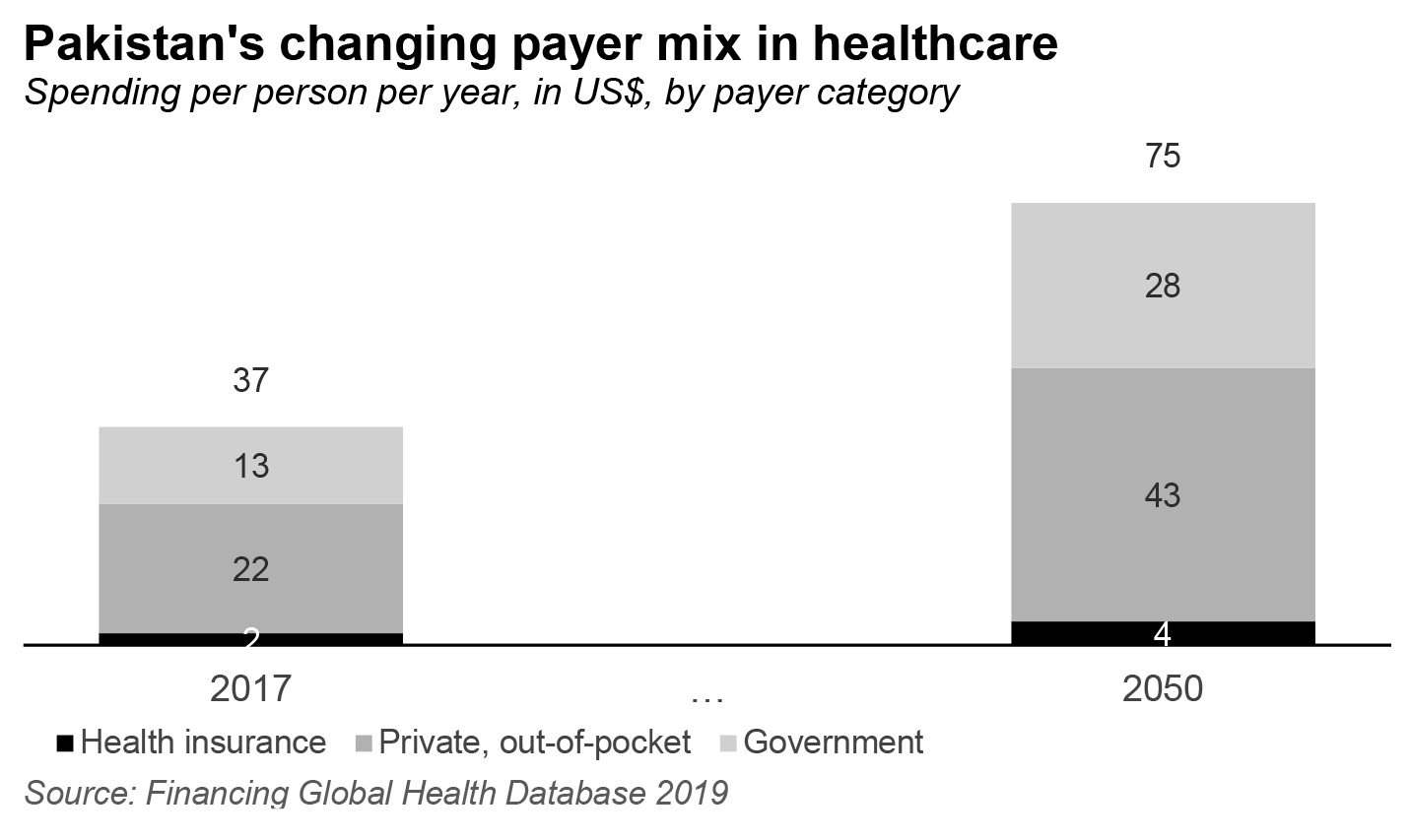

All of that means that, even though healthcare spending in Pakistan is going up substantially – and Pakistan is undergoing a revolution with respect to increased public financing of healthcare – the market is not one where the global pharmaceutical companies see big profits for themselves. It does not help that Pakistan is right next to India, which is both a much larger market, and also a much more important component of the global pharmaceutical supply chain.

Price versus volume

If you are in a business where you cannot increase your prices by as much as you would like, the best way to improve profits would then be to increase volumes, and hope that scale allows your business to squeeze out higher margins, in addition to higher overall cash flow.

It appears that the local pharmaceutical companies have understood this, whereas the foreign ones appear to still be reliant largely on price increases.

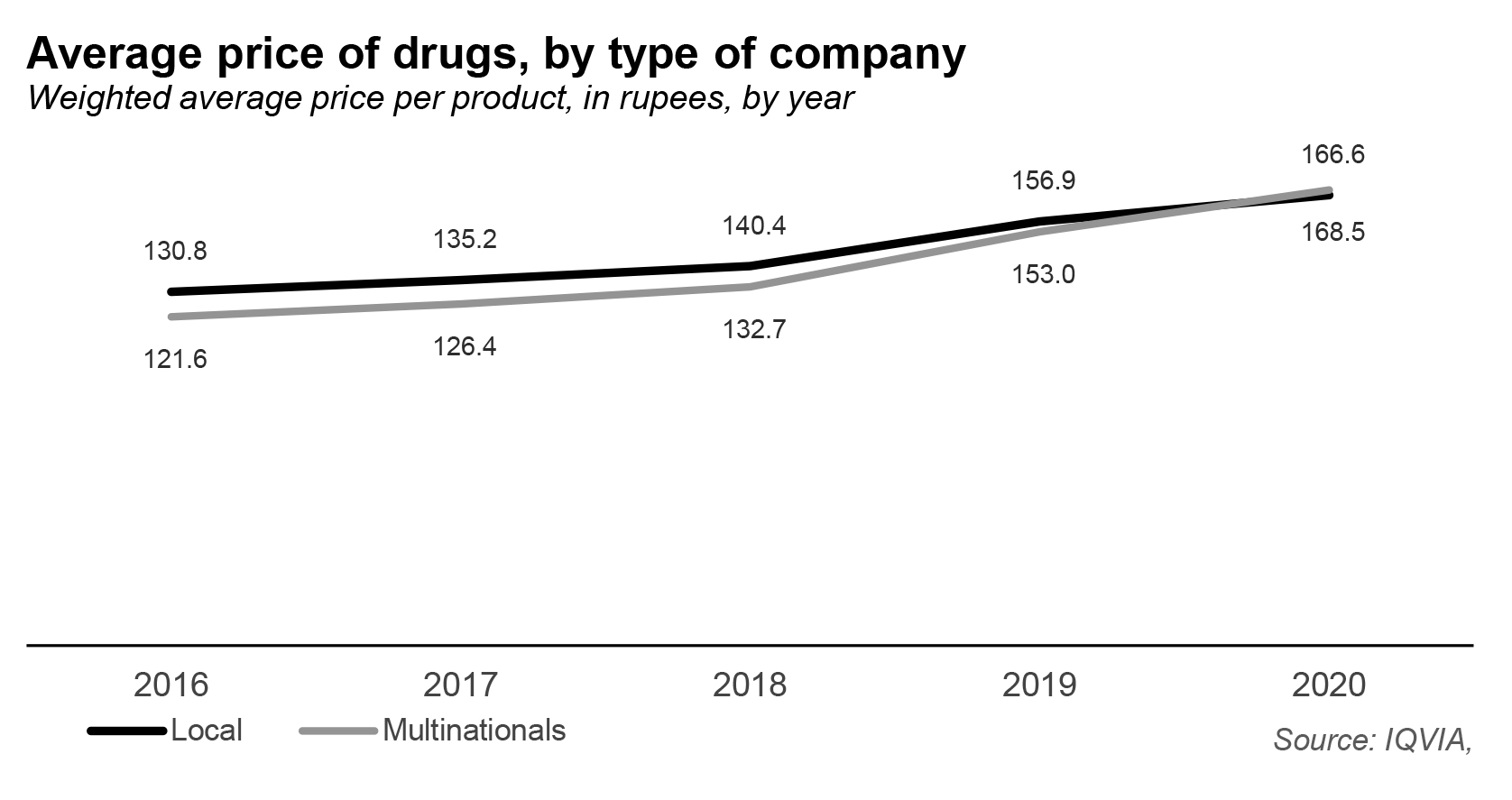

Break out the growth rates of both the local and foreign pharmaceutical companies into their components and you can see a fascinating pattern. That 12.4% revenue growth rate for local pharmaceutical companies is split almost exactly evenly between price increases (6.2% per year on average between 2016 and 2020) and volume growth (5.8% per year). For the foreign pharmaceutical companies, the numbers are very lopsided: that 9.6% per year average growth rate is 8.5% price increases and only 1.1% volume increases.

Simply put, the local companies are growing their topline by selling more products and accepting the fact that they will not be able to substantially increase prices. The foreign companies are reliant almost entirely on price increases, even though they theoretically have far more new products that they could be offering in the market that could increase their volume growth.

How did we arrive at this breakdown? We used IQVIA data on both total revenue and total volume, divided the former with the latter, and arrived at the weighted averaged ‘price’ per product that both categories of pharmaceutical companies are selling. The actual level itself is less relevant than how the two different categories of pharmaceutical companies fare relative to each other and relative to their own past data.

The weighted average prices of local products have grown at a significantly slower rate than those of the foreign products. Given the fact that both sets of companies face the exact same drug pricing regulatory regime, the reason why the local companies have seen the weighted average prices of their products go up slower than their foreign counterparts is most likely due to their introduction of lower priced products into their mix.

We specify this because it is easy to spin conspiracy theories about foreign companies being able to engage in price gouging, when the reality is that their prices are just as much determined by the government as that of local companies. Nobody is particularly happy with the prices the government gives them.

The local-foreign partnerships

So how have the local companies managed to increase their volumes if the new products are mostly controlled by foreign companies? After all, if you are a generic drug manufacturer, you have to rely on the patent expiring before you can start manufacturing new products.

There is certainly at least some of that. As patents expire in the United States, Pakistani generic drug manufacturers are free to begin producing those and offering them to local consumers are relatively affordable prices.

But at least a significant part of the new products being offered by local drug manufacturers are in partnership with innovative pharmaceutical companies in the United States that have no wholly owned subsidiary in Pakistan.

For instance, in 2014, Gilead Sciences – the US-based pharmaceutical giant – announced a partnership with Ferozsons Laboratories for the manufacturing of Sovaldi and Harvoni, two drugs that can cure hepatitis C, a disease that was previously thought of as a chronic condition that could only be managed, but not cured.

In 2020, at least three Pakistani companies – Horizon Pharma, Bio Labs, and Ferozsons – were able to begin manufacturing remdesivir, a broad-spectrum antiviral medication developed by Gilead Sciences and found to be somewhat effective in the treatment of Covid-19. And Pakistan was part of the global drug trial network for the Covid-19 vaccines developed by pharmaceutical companies based in other parts of the world.

Indeed, of the top 10 new products introduced into the Pakistani market last year, only one was introduced by a foreign pharmaceutical company. The rest were all introduced by Pakistani companies, and most were either in partnership with companies based abroad, or were generic versions of drugs whose patents have expired.

How sustainable is the local advantage?

While the local companies have done well in terms of being able to grow their toplines, particularly relative to their foreign counterparts, you will have noticed something: they are reliant entirely on research and development of drugs done elsewhere, usually in the United States and Europe, and occasionally in other parts of the world.

Either they are introducing generic versions of drugs that have lost their patents, or they are entering into partnerships with companies like Gilead, which are based in the United States and conduct most of their research there, and occasionally share it with manufacturers in countries like Pakistan. At no point are Pakistani drug companies developing innovative new products that they conducted the research to develop themselves.

This, obviously, is not entirely their fault. The pricing policies introduced by DRAP – the original 1966 law, as well as the 2015 and 2018 regulations – effectively assume that the vast majority of research and development will not be done inside Pakistan and hence barely even address the possibility of how to price an innovative product.

What that means is that if the foreign manufacturers decided one day to start importing or manufacturing more of their innovative products in Pakistan, the growth spurt that the local generic manufacturers have been able to experience over the past five years is likely to be replaced by an increase in the market share of the foreign players.

So why does that not happen? The reasons for this are complex and have to do with the production supply chain in Pakistan and the fact that a significant proportion of the world’s most complex precursor ingredients for pharmaceutical products are manufactured in India and are difficult, if not impossible, to import into Pakistan.

Why would any global pharmaceutical company invest in manufacturing complex ingredients in Pakistan? It does not have a large enough market to justify the high investments needed to make those ingredients for domestic consumption alone, and why would you set up export capacity in Pakistan when India is right next door and it is will cost just as much (and perhaps slightly more) to ship goods from Pakistan than it would from India?

Well, could the government decide to allow multinationals to import more from India, but that would run into two problems. First, the local companies would complain since it would diminish their cost advantages. After all, if the Indian generic manufacturers can export their products to Pakistan, the Pakistani generic manufacturers would likely face difficulty in maintaining their market share of their own market.

And the second biggest factor, of course, is the fact that this is something that directly pits the welfare of Pakistani citizens against our misplaced sense of ‘national pride’ against India. When, exactly, in our history, have we ever chosen the former over the latter?

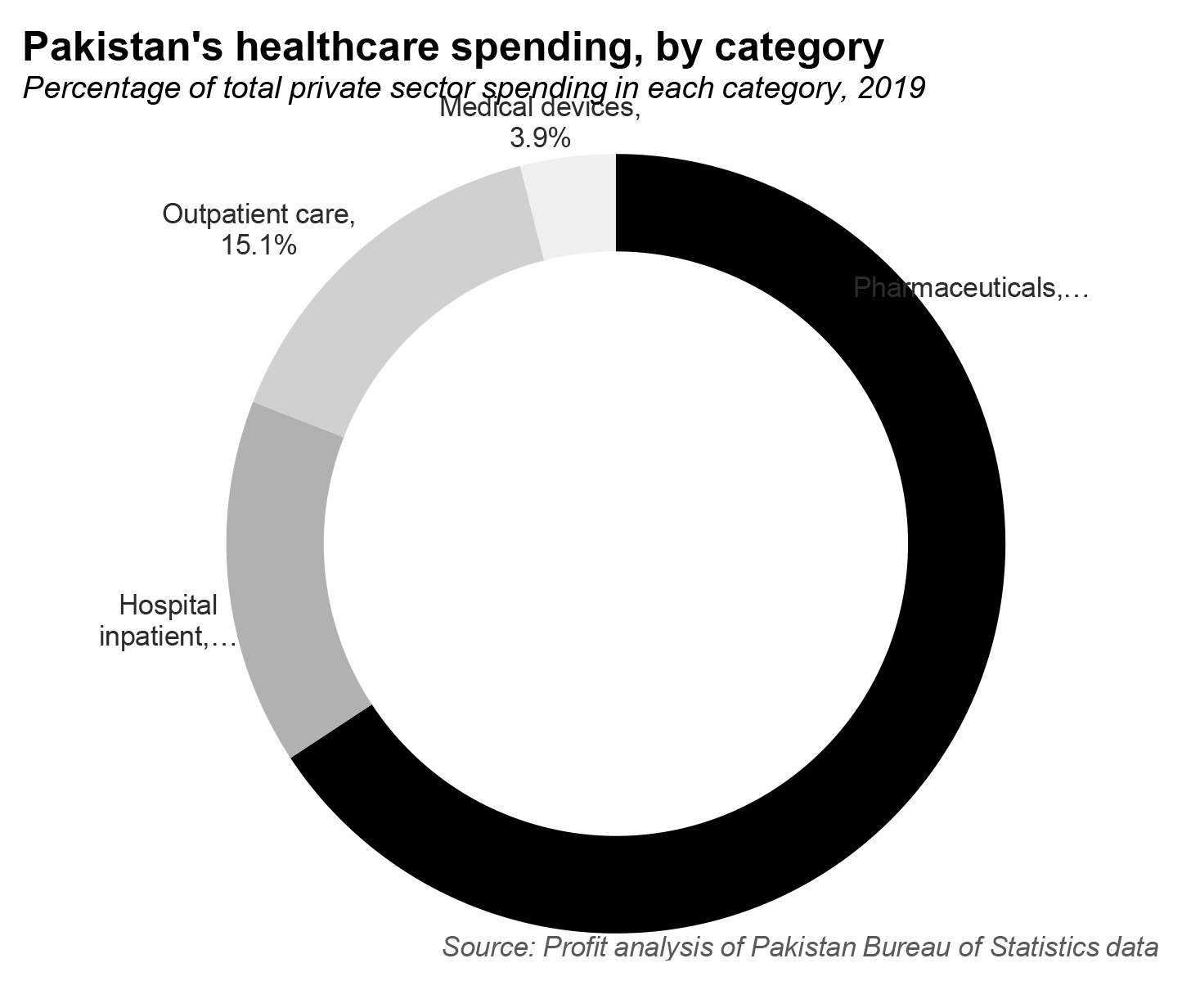

Is pharma’s dominance of healthcare itself under threat?

Pharmaceutical drugs account for approximately 62% of total healthcare spending in Pakistan, based on Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Needless to say, that makes it the single most important component of Pakistan’s healthcare sector. But with the advent of the Sehat Insaf card, which provides government-subsidised health insurance to the poorest Pakistanis, that may change.

See, the reason why pharmaceuticals are such a large part of the healthcare spending in Pakistan has to do with the fact that most Pakistanis cannot afford much else. Drugs are cheap, and readily available. And while laws exist to not allow the use of prescription drugs without a valid medical prescription, those laws are too often flouted by pharmacists.

Going to see a doctor or, more expensive still, getting a surgery are far more expensive propositions. Of course, a pill is not a substitute for a surgery in most cases, but when you cannot afford the surgery, you have to make do with the pill.

That, however, is about to change. The government’s health insurance scheme means that the poorest of Pakistanis will be able to walk into the most expensive of hospitals and get medical treatment that they need, paid for by a government insurance program up to quite generous limits.

The Sehat Insaf program will cover up Rs600,000 per year per family (Rs300,000 defined as ‘initial coverage’ and another Rs300,000 as ‘additional coverage’) for high-cost hospital procedures, and up to Rs120,000 per family per year for other types of hospital-based healthcare coverage.

These amounts may not be sufficient for the most expensive hospitals or the most expensive diseases, but they are a lot more money than what most low-income people currently have access to. And instead of begging their employers for help, they now have access to a government program that gives them similar access to healthcare services.

Given the fact that the prices of inpatient and outpatient hospital services have been reduced by government subsidy, demand for such services will increase markedly, meaning the growth segment in Pakistani healthcare will become hospitals, not pharmaceuticals.

Of course, this does not mean that drugs will not continue to grow, and indeed, some of the biggest users of drugs are hospitals themselves. But it does mean that the nature and composition of care availed by the average Pakistani is about to change in a material way, and the drug companies should expect that they will not be on the winning end of that shift.

It is likely, however, that the drug companies themselves would welcome such a shift. They have been the crutch used by the Pakistani public for a long time, and as a result, their pricing policies get extra scrutiny from the government. As other areas of healthcare get more prominence, perhaps the regulatory pressures on pharmaceutical companies will diminish, allowing them indirect growth opportunities that are currently closed off.

Losing the top position, in the end, may not be such a bad thing after all.

There is zero R&D in the local pharma sector. Not a single FDA approved manufacturing facility compared to multiple facilities in India and Bangladesh should be a wake up call for the regulatory body. Exporting to low income countries does not show that out pharma has come up the curve when all APIs have to be either imported from India or China!!!

yeah u r right no approvals from recognized global bodies and no r and d

I THINK NOW LOCAL COMPANEIS HAVE MORE fda approved plants in pakistan as well

all data here are so useful we also know best website about these information vision pharma pk