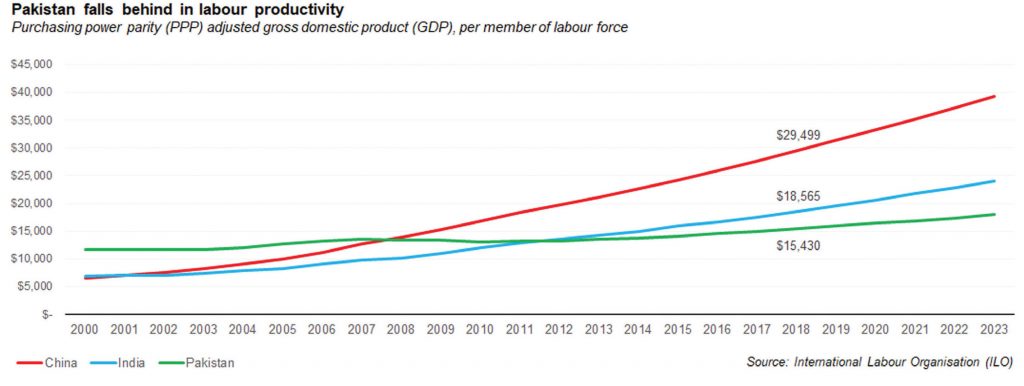

In the year 2000, Pakistan’s labour productivity exceeded that of both China and India. A decade later, China had more than doubled its labour productivity and surpassed Pakistan in 2008, while India had caught up and eventually exceeded Pakistan in 2012. So what happened? How and why did Pakistan fall behind? And what exactly is labour productivity and why is it important?

Economists define labour productivity as the amount of economic output per worker in the economy. As a mathematical matter, it is calculated by dividing the gross domestic product (GDP), adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), by the total size of the labour force.

Pakistan’s labour productivity is estimated at $15,430 in 2018, according to data from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), having grown at an average of 1.5% per year since the year 2000. India’s labour productivity is 20% higher, at $18,565, having grown at a much faster average of 5.7% per year during that same time period. China’s labour productivity is $29,499, having grown at 8.8% per year since 2000.

Labour productivity is one of the hallmarks of development. It drives economic growth and affects everyone in the economy. A highly productive economy will be able to produce more goods or services with the same amount of resource, or produce the same level of goods and services with less resources. For businesses, higher labour productivity will bear greater profits whereas for the workers, it can translate into higher wages and better working conditions. For a government, a higher level of productivity can bring in more tax revenues.

So where did Pakistan fall short?

Profit’s conversations with business owners and experts suggest that Pakistan’s workforce, in all its classifications, lack two big things: skills, and a strong work ethic, relative to labour in developed economies.

Pakistani employers, by and large, are too short-sighted to invest in the productivity of their labour force, which in turn means that the labour force is paid very little, which results in both shirking and a lack of sustained effort, which in turn results in a low level of trust between business owners and labour, and therefore the business owners continue to not invest in their labour force.

Moreover, firms in Pakistan mostly reek of structural flaws that make the businesses and ultimately the whole economy less productive.

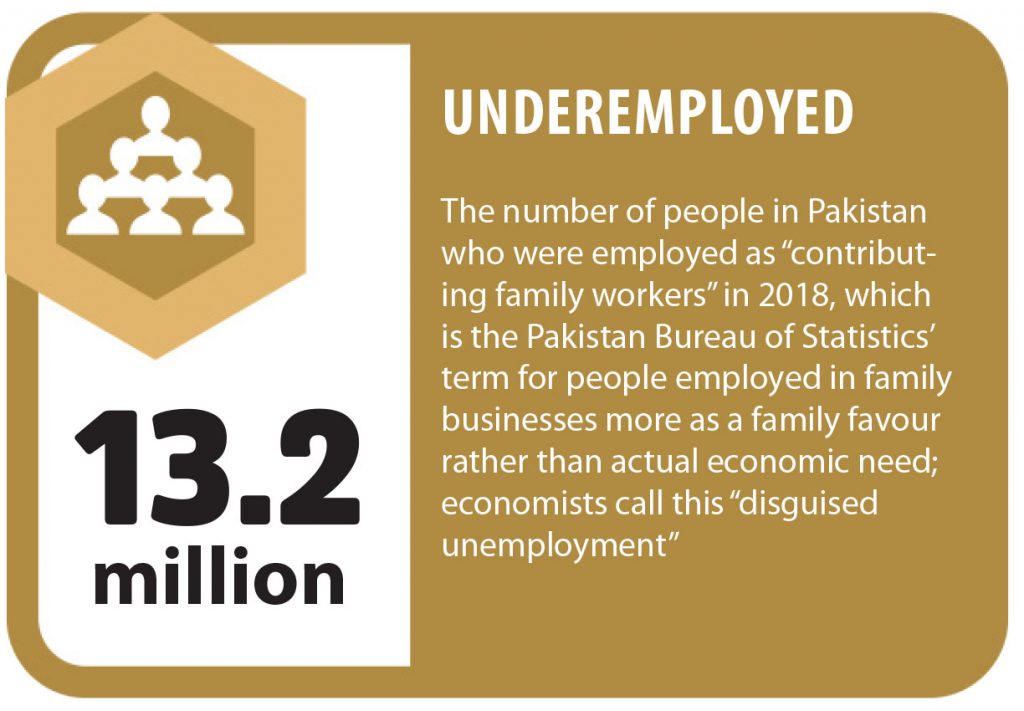

And then there is the problem of what might be called ‘disguised unemployment’. That describes a scenario where a person is employed, but does not have much to do, and hence is not really working. That can happen in circumstances where a person is employed by a business run by members of their immediate or extended family. While the business does not need their labour, it is employing them as a form of family support.

“That person is not contributing towards productivity and even if he is removed from his post, labour productivity will not come down. The practise is common in the services sector of Pakistan, which forms about 53% of our GDP. The sector is large enough to absorb the labour employed on the basis of relationships rather than qualification or productivity. While an extra person might not increase the productivity of the business, his employment will bring down average productivity,” Dr S Akbar Zaidi, an expert on economy told Profit, terming such a form as non-productive employment.

One might think that this is a relatively uncommon phenomenon, but it is so prevalent that the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics actually measures it, calling it “contributing family workers”, who form 21.4% of the total labour force, or 13.2 million people.

In the manufacturing sector, productivity needs to be seen as the number of people needed to manufacture a product. If a product is being produced by, for instance, 20 people at one place and the same product is being made by 8 people at another place, it means that the 12 extra people can be engaged to do something else.

Pakistani businesses tend to have a significant over-staffing problem, and at times it renders them uncompetitive relative to their foreign peers. It can even result in them being unable to raise capital from overseas investors.

Shehzad Ilahi, owner of garments manufacturing company Mushrooms, gave the example of a Pakistani textile company that was selling one of its manufacturing units: “The Chinese were considering buying the unit. They were, however, appalled when they got to know about the number of managers running that unit. They could get the same work done by a smaller number of managers. The sale eventually did not go through.”

“Another example is the government departments. If you reduce the workforce to half in these departments, their productivity will not be halved. It might improve actually. When half of these people will leave, the remaining half will have to be more productive,” Dr Zaidi says.

Lack of skills and training

It is no surprise that the Pakistani business owners, especially the ones operating export-oriented industries such as textiles, are dreading the thought of competing with the international players because they never invested in training and developing the skills of their labour force.

Productivity is intimately linked with the skills of a labour and is particularly important in the manufacturing sector. It is indispensable because if somebody is skillful in operating a machine, he’ll produce more products from it as compared to the one who is not that skillful. To improve skills requires putting the workforce through training and skills development programmes; a taboo in the Pakistani economy.

“Without requisite training, a labourer cannot be deployed on the [production] floor,” says Yameenuddin Ahmad, CEO of Timelenders, a firm that provides strategic and time management trainings to organisations. “In China or Philippines or Europe, workers have certifications, qualifying them for a certain job. However, if you go on the production floors of factories here in Pakistan, you won’t find such training certificates. A machine operator works on the basis of experience. It has put a whole set of industries at the risk of being entirely wiped out because the labour they had is about to retire but the new labour has not been trained.”

“Industrial owners in Pakistan admit that they did not realize that the textile industry will go through such massive technological changes. We don’t have a long-term vision. So, you cannot blame labour alone for the low productivity. Owners have played their part as well. There is no time management or training. Because trainings incur a cost; learning is expensive. The results are in front of you now,” he says.

Besides trainings, access to technology and the ability to leverage it are crucial for productivity. In the absence of technology, only traditional tasks can be performed but since the world is moving towards new value added and upstream products, technological savviness is a must.

“That requires literacy. If you can read things, you can better use technology. In the absence of literacy, you’ll only be able to do outdated tasks. Creating an iPhone in Pakistan would be more time consuming since technology is limited here and literacy is low. Where literacy is high and technology is advanced, it will take less time to produce a similar product,” Dr S Akbar Zaidi says.

A matter of work ethic?

Another core problem is the lack of a strong work ethic. From the moment they are small children, Pakistani students enter an educational system that does not require of them a strong work ethic. It does not require consistent hard work, and tends to focus only on end-of-year or end-of-semester examinations, rather than requiring students to work diligently every day.

The problem starts at home, according to Yameen, as parents have no vision about where they want their child to be. Furthermore, they have no mechanism to make the child a productive individual.

Sajidoon Nadeem, co-founder at a software firm, MindBlaze Technologies, sees lack of ethics as an issue involving not only work, it also includes how a person behaves with his/her peers and one’s demeanor towards his/her superiors, in general. He sees irresponsibility or un-professionalism as a product of negligence on part of parents to build strong ethos during a person’s childhood. “Why a worker does not work efficiently can simply be because of unprofessionalism or irresponsibility that he has developed over childhood,” he says.

But if we are to hold the above argument true, why is it that the same person, when he moves abroad, becomes more productive for the same sort of a role that he had here? It is not seldom that Pakistanis move abroad chasing lucrative careers and surprisingly attain stellar levels of work performance there. The same workers over here would give lethargic productivity and slack overwhelmingly.

The answer lies in the work balance offered by foreign employers with monetary motivations that include better compensation and incentives, in tandem with intensive monitoring protocols and accountability to keep the workers from slacking.

“Over there, people are worried about losing their jobs. In Pakistan, they’ll simply say that we’ll find another one. If you have spent money to go to work in another country, you’ll be serious about your job,” says Dr Zaidi. “Another reason is that when people see others are slacking about their work, they slack too. If they see everybody is doing a good job, they’ll work harder as well.”

While slacking is a global phenomenon, it is extraordinary in Pakistan. It is contagious and trickles down a hierarchy. “To start with, our business owners are slackers. Most of them are absolutely unproductive. They arrive at office at noon when they should start their work early,” says Yameen.

Sajidoon argues that lower productivity can be seen as a consequence of low monetary motivation or simply because an employee is not satisfied with his job. That is topped-off by a corporate culture that also lacks ethical values.

“Labour laws are not implemented here properly. Employers treat employees like slaves. That’s the sort of culture due to which a tussle erupts between employer and employee, leading to employee ceasing to care about the employer. The companies, instead of solving the problem at its root cause, hire managers on top of it and they start playing politics. This is the sort of corporate culture which leads to slacking. If you take care of your employees, they’ll take care of you. And if you’re doing that and your employee is still not working efficiently, he is not worthy of the job then,” he says.

“Monetary motivation is low to the point of tyranny in Pakistan. If your labour does not have enough money for everyday needs of his family, how can you expect productivity from him? Business owners have made money but did not spend it on their own people. They were neither spent on their competency nor on their financial stability,” says Yameen.

So given the right motivation, monetary and other forms such as respect and value, Pakistanis can be equally hard working, according to Sajidoon.

Working under such motivations, however, does not imply that a person has better work ethics. “In Pakistan, government workers are hedged from losing their jobs. That alleviates the fear and they do not work diligently. In the private sector as well, if you’re not working, you have a threat of getting fired. But working under a ‘threat’ does not count as having a good work ethic,” Dr Zaidi says.

How can firms curb slacking?

So how can firms crack down on shirking, or the act of not working during hours that are meant to be for work?

MindBlaze’s Sajidoon says that cyber slacking has reduced over the years because of certain supervision and monitoring protocols that they have implemented. “There are software and tools that they have installed to monitor the activities of their employees that has helped improve productivity,” he says.

Software firm Soft Pyramid’s CTO Farooq Khalid said that his firm has also deployed monitoring tools that keep an eye on how much time an employee spends on a certain task. “That helps keep a track on the employees. The tools take screenshots of employees’ activity on the computer when they are in the office and tracks how much time an employee spends on a certain task. Our employees have access to social media sites such as Facebook and they use it for certain durations. But as long as the client’s targets are being met and projects are being completed on time, there is no issue with that.”

Profit also inquired what should be the long-term strategy for the businesses to improve productivity.

“Businesses need to have a long-term vision decide their course of action after analyzing where the world is going to be in the next 10 years. Once the long-term vision is clear, the workforce should be developed on that line,” Yameen says, stressing that businesses should train new people and start accommodating them in the industries. There should be concomitant efforts to extenuate the problems faced by their labour and bring them at a monetary level where they do not face fundamental existence problems.

On a personal level, a worker needs to understand how his job aligns with the vision of the company and how he can add value to his job. The fourth industrial revolution that we are experiencing right now is all about adding value. Since the competition is tough, it is plausible to work on competencies to improve the weaker ones and develop the ones that are not there but are needed, he says.

Introspection at both the individual and organizational levels will improve the overall productivity of the businesses, which will eventually translate into higher productivity for the overall economy.