One million, four hundred and twenty-nine thousand, nine hundred and seventy-six (1,429,976).

That is the number of taxpaying entities that the Federal Board of Revenues (FBR) says existed in Pakistan in 2017, a number that the government has spent the previous four years refining to get an accurate count of exactly who is a taxpayer in Pakistan. Except that the number is probably still not accurate.

Any government that takes office after the elections in exactly a month’s time (July 25) needs to confront the fact that it will be relying on the FBR to raise the revenue it needs to pay for any policy agenda they may have, and the FBR is an organisation that cannot even accurately answer a question as basic as: how many taxpayers are there in Pakistan?

To that end, Miftah Ismail, the former federal finance minister under the Nawaz Administration and likely future finance minister should the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) win re-election, appears to have an idea that just might work: outsourcing a substantial portion of the work currently done by the FBR to private entities that are incentivised to increase revenue collection.

The PML-N plan to increase tax collection

Ismail laid out the proposal in an interview with Business Recorder, where he outlined what he saw as a public-private partnership that might help expand the country’s tax base, using a plan that has its origins under previous administrations.

In a project that originally began under the Zardari Administration, then FBR Chairman Ali Arshad Hakeem was trying to compile a list of the 3 million or so Pakistanis who appear to have lifestyles that would justify them paying taxes, but for whom the government has no record of paying any taxes. The plan involves getting the help of an agency that, at least on the surface, appears to have nothing to do with taxation.

The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) has access to a significant amount of data about individuals since it is the issuer of Computerised National Identity Cards (CNICs), which are needed for most transactions. Using that data, NADRA is able to compile profiles of suspected tax evaders. It knows where they live, where and how often they travel abroad, what cars they own, how many bank accounts they have (but not how much is in those bank accounts), and even whether they had more than one wife.

NADRA also has significantly better capabilities in terms of being able to use Big Data analytics to not just identify these suspected tax evaders but also estimate how much they should pay in taxes. It is an audacious plan: using the power of Big Data to crack down on tax evasion, with the FBR being aided by the database and mathematical wunderkinds at NADRA.

The Nawaz Administration appears to be going one step further, however: the government would not just deploy NADRA’s data capabilities in identifying the tax evaders, it would then also try to circumvent the rampant corruption problem at the FBR by outsourcing the process of issuing tax notices, collecting taxes, and auditing financial records of tax-payers to private contractors.

The underlying assumption of this component of the plan is that tax evasion would simply not be possible without corruption at the FBR, and that the best way to get around that problem is to outsource all interactions between the government and taxpayers to a neutral third party that has an incentive structure more aligned with that of the government, and not the Civil Service of Pakistan, which dominates the ranks of the FBR. In effect, the government is assuming that the Civil Service cannot be trusted to favour the interests of the government and people of Pakistan.

How we got into this mess

Needless to say, that is a complicated plan and predicated on a series of assumptions that would be difficult to understand without first understanding just how Pakistan arrived at this mess.

The fundamental problem began almost immediately after Partition when the government of Pakistan appeared to make a decision not to impose significant amounts of taxes on the wealthy elite of the country, through a variety of exemptions and loopholes. Income derived from agriculture, for instance, was either not taxed or taxed at absurdly low rates, despite the fact that at the time of independence in 1947, the overwhelming majority of Pakistan’s wealthy elite included large rural landowners.

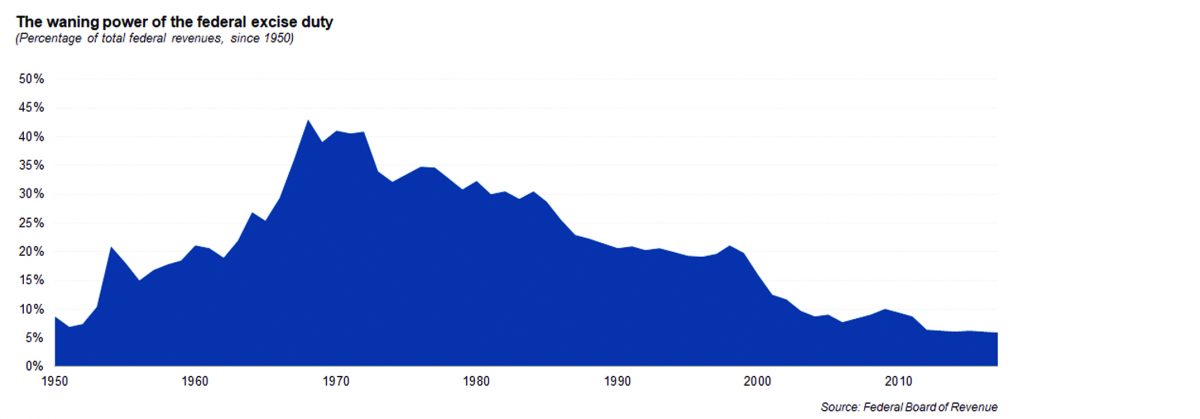

The industrial elite did pay more in taxes than the rural elite, but even they managed to ensure that the taxes – even the so-called direct taxes – would be structured in a way that they could simply pass on the burden of the tax to their customers: hence the importance of customs and the federal excise duty in the early years of the country’s existence.

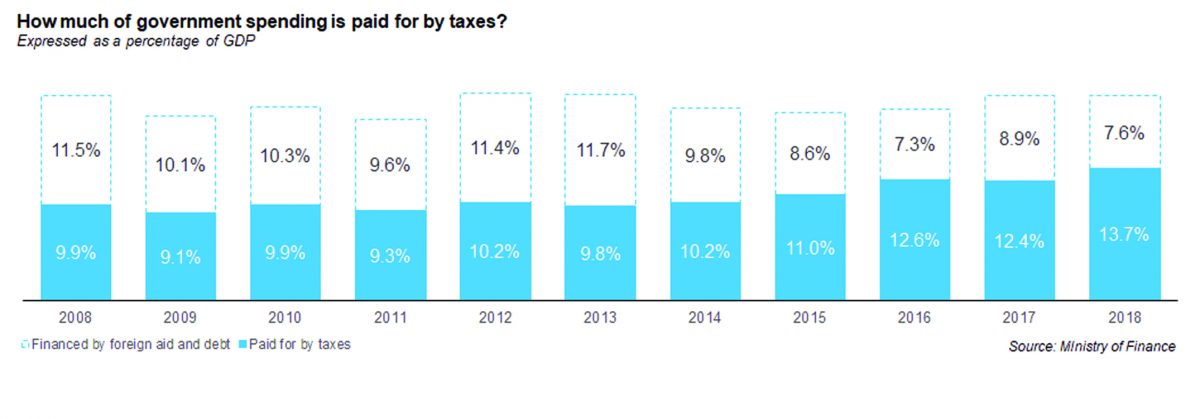

As a result of these policies, Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio was abysmally low for the first decade after Partition, hovering around the 6% mark, and dipping as low as 4.66% in fiscal years 1954 and 1955 (Pakistan’s fiscal year runs from July 1 of the previous year through June 30).

Over time, the government has begun to rely on a variety of different taxes, though at a surprisingly slow pace. For instance, Pakistan was effectively using the tax regime originally introduced by the British Raj under the Income Tax Act of 1922 until the Musharraf Administration, which in 2002 introduced a new tax law that simplified the income tax systems. (Technically, the Zia Administration introduced an income tax ordinance in 1979, but independent analysts believe that the law made no substantive changes.)

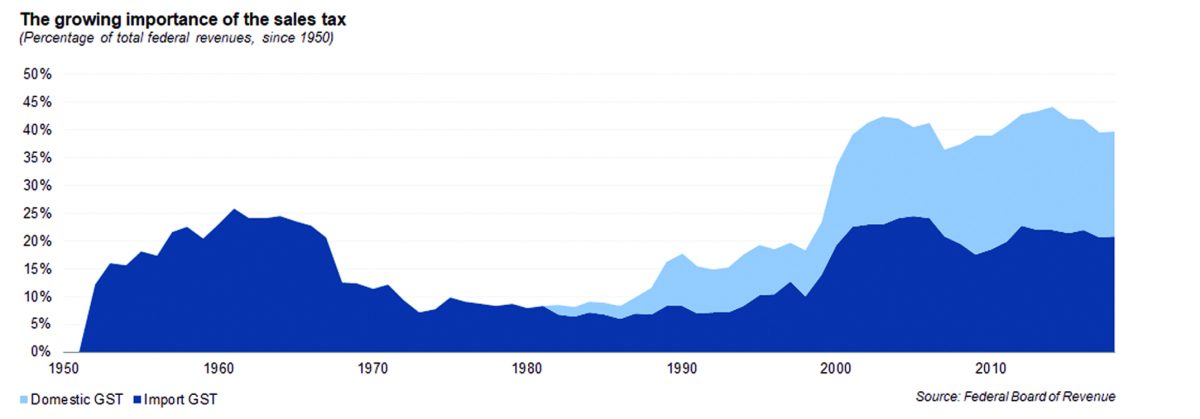

The most important innovation in Pakistan was the introduction of the domestic sales tax, which allowed the government to begin taxing domestic consumption rather than production capacity (which is what the federal excise tax is levied on).

That innovation took place in fiscal year 1982. From that point on, the sales tax went from accounting for no more than 10% of total federal tax collection in the 1970s to consistently over 40% of total tax collection today.

Another big change took place as a result of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and the 7th National Finance Commission Award, both of which passed in fiscal 2010 and went into effect from fiscal year 2011. That law allowed the provinces to start collecting more of their own taxes, and provincial governments were given more autonomy to spend that money on their own. As a result, provincial governments have finally begun collecting more of the total taxes paid by Pakistanis, a phenomenon that has improved the ability of the government as a whole to pay its own bills.

As of the fiscal year 2018, the government expects the tax-to-GDP ratio to hit 13.7%. If it is successful in achieving that goal, that would be the highest tax-to-GDP ratio in Pakistan’s history, a fact that is both an achievement for the Nawaz Administration and a travesty for Pakistan as a whole.

The problem with the FBR’s taxpayer data

Since 2013, the FBR has undertaken an effort to increase the pain of not being a taxpayer, an effort the government has aided by enacting laws that increase transaction costs and taxes for people who do not file their tax returns. As a result, the FBR has begun publishing a list of tax filers in the country, which allows them to be exempted from the measures being taken against people who do not file their tax returns.

However, the list – and the FBR’s processes that produce it – are deeply flawed.

The list published by the FBR includes hundreds of thousands of names of people who have evaded their taxes and excludes the names of hundreds of thousands of hardworking Pakistanis who pay their taxes. Indeed, the list is more useful in what it does not reveal than what it does. It says more about the FBR’s limited capabilities than it does about who pays taxes in Pakistan and who does not.

Let’s start at the very beginning: the list covers only federal income taxes for entities that filed an income tax return in the most recent year (currently data is available for fiscal year 2017), or for whom their withholding agent filed income tax information.

What it does not include are people whose income taxes were withheld by their employer, or other sources, and who did not file their tax returns. (It does include people whose employer filed their individual tax data.) And barring a few FBR and finance ministry officials who clearly had the sense to file their returns before the list was published, it does not include a large proportion of the over 700,000 government employees who all pay their taxes, but the vast majority of whom do not file their returns.

This is why you cannot find the names of many generals or judges: the Accountant General of Pakistan Revenue simply gives the government a lump sum for all federal employees, including the military, but provides no breakdown. (The FBR has no clue as to whether the income tax withholding process is even being done properly.)

This is an important distinction: there is a difference between paying your taxes and filing your tax returns. Both are legal requirements, but only failure to do the former gets you labelled a tax evader. In fact, it is possible to evade taxes and still be a tax-filer: by submitting falsified documents, something that the FBR’s electronic systems do not have the ability to catch. It is also possible to declare that you have paid one amount and actually pay a lower amount, and the FBR’s systems will not catch that either.

Hence, the database that has been released includes hundreds of thousands of entities against whom there is a “tax paid” amount of zero. Not all of these entities are, of course, evading their taxes. Some are companies that had net losses and do not owe taxes. Others are companies in sectors that are exempted from paying income taxes (such as exporters). And some individuals earn less than the amount that is taxable, or can claim enough deductions and exemptions to minimise their liabilities to zero.

The database also does not include any information about general sales taxes (GST), federal excise duties (FED), or customs duties paid by any company or individual business owner. That difference is important. On the basis of income taxes, the state-owned Oil & Gas Development Company is the biggest taxpayer in Pakistan, paying nearly Rs25 billion in 2017. If GST and FED are included, the top spot goes to Pakistan Tobacco Company, which paid just under Rs71.6 billion in 2017.

And taxes paid are not a reflection of a person’s wealth or assets. Mian Muhammad Mansha, for instance, is the richest man in Pakistan, but that is by assets. His income is high, but probably not the highest in the country, since most of his wealth is tied in the shares he owns in some of the largest companies in Pakistan, shares he is unlikely to sell any time soon. Hence, while Mansha is among the highest taxpayers in the country, but he is not the biggest taxpayer. (Disclosure: Mr Mansha is a shareholder as the publisher of Profit.)

Income taxes are levied on the actual cash flow one gets in a given year from non-exempt sources, not on the total asset base that delivers those cash flows.

So how many taxpayers should there be in Pakistan? A lot smaller than you might think.

How many taxpayers should Pakistan have?

Let us start off with the fact that the total labour force as a percentage of the country’s population is only about 38.2%, according to the Pakistan Labour Force Survey. Compare that with numbers in Europe and North America that typically exceed 60% of the total population. Why is Pakistan’s labour force so small relative to its population? We have a lot of children. The median Pakistani is 23 years old, which means that half of the population is less than or equal to that age.

Given a population of 207 million in 2017, that leaves a total labour force that is approximately 79.4 million people. And within that labour force, a surprisingly small number of people earn an income large enough to be eligible to pay income taxes, which is generally the only type of tax that most individuals are eligible to file tax returns for. (We all pay sales taxes, but sales tax returns are filed by the companies that sell those goods to us, or to the retailers and other entities from whom we buy those goods and services.)

Here is where the numbers get very interesting. Under the current law, which expires on June 30, any Pakistani individual who makes more than Rs400,000 a year (Rs33,333 per month) is eligible to pay their taxes. According to Profit’s analysis of income survey data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, an estimated 14.6 million people in Pakistan make more than that amount in a given month. That comes to approximately 18.4% of the total labour force and just over 7% of the total population.

This, by the way, assumes that none of the individuals in question derive their income from exempt sources, such as agriculture. Factoring that amount in takes the numbers down by approximately one-third, to about 12% of the total labour force and about 4.7% of the total population.

However, with the new budget that passed Parliament in April, as of July 1 of this year, the minimum taxable income has gone up to Rs1,200,000 a year (Rs100,000 a month). The proportion of Pakistanis who earn that amount as individuals is miniscule: just 650,000 individuals or 0.8% of the labour force in 2017, or 0.3% of the total population.

Of course, the dataset we rely on – the Household Integrated Economic Survey run – probably systematically undercounts the number of people who make more than Rs100,000 a year. Nonetheless, one could multiply that number by 5 and still arrive at a number that is less than 5% of the labour force and only around 3% of the total population.

These numbers, by the way, is why the government relies so heavily on sales taxes rather than income taxes: at least 93% of the people in Pakistan simply do not make enough money to pay income taxes.

But even if one were to take this greatly reduced number of eligible taxpayers, the FBR database is effectively an admission that the government is only collecting taxes from about 10% of the potential taxpayer population.

Can outsourcing help?

The PML-N plan – as outlined by Miftah Ismail – is effectively an admission that the FBR is a congenitally corrupt organisation that is simply beyond repair. But the PML-N is not proposing undertaking the difficult task of implementing civil services reforms, which they assume would be stymied by the simple fact that any reform agenda would have to be implemented by the sclerotic and perennially corrupt civil service itself.

Instead of trying to tackle that Catch-22 situation, the PML-N is proposing outsourcing the parts of the FBR’s job that are most prone to corruption: issuing notices, collecting payments, and conducting audits. In other words, any task that involves an FBR officer interacting directly with a taxpayer.

Of course, that would still leave the FBR with the task of administering the tax machinery as a whole, but with so many essential functions outsourced, the FBR would functionally turn into a near-redundant entity, and the task of tax collection in Pakistan will have effectively been privatised.

Yet it is not immediately obvious as to why this essential government function needs to be privatised. Indeed, there is evidence from Pakistan itself to suggest that simply re-aligning the incentive structures of official within the government’s existing tax collection machinery can produce significantly improved results with respect to revenue collection.

A landmark study was conducted by three academics in Punjab, who published a working paper in 2014 with the International Growth Center (IGC) outlining their results. The academics are Asim Khwaja, a professor of public policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, Benjamin Olken, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Adnan Khan, a researcher at the London School of Economics. The International Growth Centre is a research centre based at the London School of Economics operated in partnership with the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford.

These three academics were able to conduct an experiment in Punjab, where they introduced performance pay incentives for property taxes in the province. The new incentive scheme appears to have been quite successful, resulting in a 46% increase in revenue collections among those officials who were offered the performance incentives compared to a 28% increase in revenue collection in the comparison group who were not offered the incentives.

In short, it appears to be possible to improve revenue collection in even some of the most corrupt and incompetent segments of the government’s tax collection machinery without the need to privatise the essential functions of government.

It is still possible that the results of an experimental scheme in one area of tax collection will not necessarily translate into success in another area. After all, the sums of money that government officials handle at the Large Taxpayer Units in Karachi and Lahore are much higher than those handled by the property tax units across Punjab that were studied in the IGC paper.

Nonetheless, it would appear that the government should at least be attempting to improve the performance of its own civil servants through a scheme that has at least provisionally shown results before abandoning all hope and rushing headlong into privatisation of an essential function of the state. After all, the historical experience of governments that dole out contracts for revenue collection to private entities – whether it be the Nawabs of Bengal outsourcing tax collection to the British East India Company or Louis XVI outsourcing tax collection in France to private individuals – tends to not end well for the outsourcers.

Mr Ismail would do well to read up on his economic history.