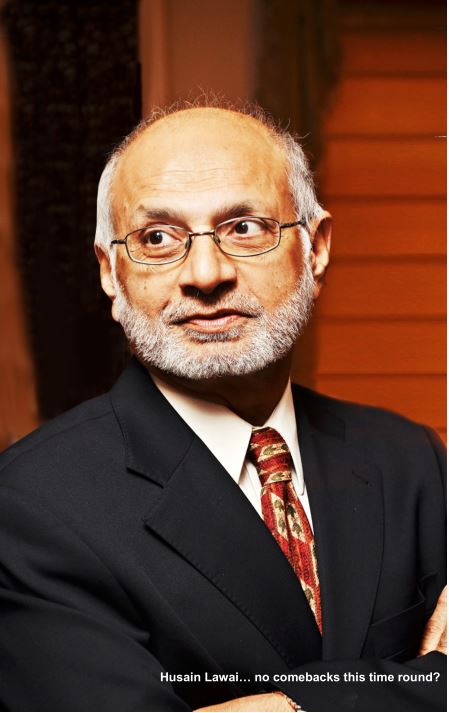

In early 2008, the party in the Pakistani financial services sector had been going on for just under a decade but one man who could easily have been at the apex of it all was missing out on it. Husain Lawai was present – indeed one of the founding architects – of the transition of Pakistan’s banking system from a nationalized, sclerotic mess to the dynamic, privatized sector it was about to become.

Lawai, 73, graduated from the Institute of Business Administration in Karachi, then Pakistan’s only business school, with an MBA in 1967, and started working for MCB Bank, rising through the ranks in corporate banking. By the 1980s, he had moved on to leading Emirates NBD Bank in Pakistan and East Asia before moving on in 1987 to help set up Faysal Islamic Bank’s branches in Pakistan.

In November 1990, Nawaz Sharif took office as prime minister of Pakistan for the first time and almost immediately set about trying to reverse the disastrous nationalization policies that former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto put in place in 1974.

Among the first banks to be put up for auction was MCB Bank, which was privatised in January 1991 after a consortium of 12 leading industrialists was declared the winner of the auction. Lawai, who was the then CEO of Faysal Islamic Bank, was serving as one of the institutions advising this consortium on the transaction.

Once the bank was privatised and the consortium assumed management control, Lawai was invited to become the CEO of MCB Bank.

It appeared to be a moment of triumph for Lawai, having gone from leading the tiny operations of a foreign bank to becoming the 46-year-old CEO of the fourth largest bank in the country. However, in retrospect, it may have been too early to celebrate.

While Pakistan’s banking sector was beginning to be privatised, it had not yet completely shaken off the shackles of political interference. And by most accounts, Lawai, having spent most of his career in nationalised banks, was used to cultivating relationships with politicians. Among the politicians with whom Lawai developed a close relationship was Asif Ali Zardari. That resulted in Lawai’s first fall from grace.

In October 1996, shortly after the second Benazir Bhutto administration was removed from office by then-President Farooq Ahmed Khan Leghari, the government began investigating corruption allegations against several members of that administration, including Zardari. Among other accusations was the allegation that Zardari had laundered and illegally remitted billions of rupees outside Pakistan with the help of businessman Abdur Razzaq Yakoob (known more famously by his initials, ARY).

Lawai got caught up in that investigation, and it was alleged by the governments of both Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates, that he had willingly allowed his bank to be used as a vehicle for laundering money from Pakistan to the UAE.

The money laundering charges against Lawai were never proven, and in 2002, a court in the UAE exonerated him. But when they first surfaced in 1996, they were serious enough for him to have to leave the country, first to the UAE and then on to London.

It probably does not help that, after the allegations surfaced, he was fired from his position as CEO of MCB Bank and the man who was widely perceived to be his political patron, Zardari, had been thrown in jail on charges of corruption.

Lawai spent 12 long years in exile, years that could have been the peak of his career. At the age of 46, he had become the CEO of the fourth-largest bank in the country. By the time he was 51, he was out of a job and facing money laundering charges. It was a stunning fall from grace.

He was on the outside, looking in, and hungry to prove his mettle.

Finally, by early 2008, matters had turned in his favour. Having already been acquitted in the UAE in 2002, he was finally acquitted of the money laundering charges against him in Pakistan in 2008.

And he seems to have been observing Pakistan’s banking system closely enough to realise the opportunity that presented itself that year: the smallest banks were struggling to survive, not having enough scale to be interesting enough to the best sources of corporate credit and hence collapsing under the dual weight of high operating costs and bad loans.

Lawai’s time in Dubai had not been spent idly, and he had provided his consulting services to several of the Middle East’s wealthy families. In late 2008, he persuaded one of them to back him in his idea: merge the smallest three banks of the Pakistani banking system, and shore up their capital, which would give them the scale and the stability to compete with at least the mid-tier banks.

His first target was Arif Habib, for which he bid in October 2008 and completed the transaction in July 2009. He then used this vehicle to bid for Mybank (October 2009) and Atlas Bank (November 2009). The last of the three transactions closed on June 30, 2011, by which time the bank had already been renamed Summit Bank.

A product of pure ego, magnified three times over

Summit Bank is a sausage of a bank, strewn together in a slapdash series of three mergers that took place between 2009 and 2011 when Suroor Investments, began buying out the smallest, crappiest publicly listed banks in Pakistan. Suroor is a Mauritius-registered special purpose vehicle owned by Nasser Abdulla Hussain Lootah, a member of one of the oldest and wealthiest families in Dubai. It is still the majority (51%) shareholder in Summit Bank and it was Lootah’s money that Lawai used to make his comeback in the Pakistani banking market.

Dawood/Atlas Bank

In 2004, when the Bank of Ceylon decided to close down its tiny operations in Pakistan, Hussain Dawood bought them and renamed them Dawood Bank. However, while he bought the bank, it appears that he never had a clear strategy for running it.

The bank, if anything, was a distraction and in 2006, he sold it off to somebody who clearly valued the prestige of owning a bank far more than he did: Yusuf Shirazi’s Atlas Group.

Strictly speaking, the Shirazis should not have felt the need to own a bank. They were and are one of the top five richest families in Lahore, probably in the top three, and easily part of the social elite of Pakistan. The problem for them, however, appears to have been the fact that the other two of the top three did own banks: Mian Muhammad Mansha owns MCB Bank now, while the Sheikh family possesses Allied Bank. In addition to owning Atlas Honda (motorcycle manufacturing) and Honda Atlas Cars, the Shirazis owned other financial institutions, such as an insurance company (bought in 1980), an investment bank (created in 1990), and a leasing company (created in 1989).

Maybe that is what made them think: how hard could owning a bank be?

It turns out that it could be extremely hard, especially with the family remaining focused largely on their industrial interests. For one thing, they got the timing wrong. They bought Dawood Bank in February 2006, which was just in time for their two-year expansion drive to land right in the middle of the worst financial crisis in Pakistan’s history. For another, while they did not seem to be completely terrible at lending (non-performing loans were around 10% of the lending book when they sold the bank), they seemed to be in an undue rush to get deposits and were willing to give the house away to get them, meaning their net interest margin was essentially zero.

Needless to say, it did not end well.

By the third quarter of 2008, Atlas was looking for a buyer for their bank, with the first candidate being KASB Bank in October 2008, though that deal never went through, largely over price disagreements (although that is probably code for ‘KASB had less money than they were willing to let on’.) In April 2009, the Shirazis tried to sell the bank to Saudi-Pak Bank (now Silkbank), but even that transaction did not go through. Finally, in November 2009, they sold Atlas Bank to Suroor Investments for Rs4.50 per share, or 0.84x its book value at the time.

Arif Habib Bank

Meanwhile, the bank that actually became the legal predecessor company to Summit Bank started its life as Arif Habib Bank.

Arif Habib, not related to the Habib family, was born in 1953 as the youngest of nine children. Arif’s father was a tea merchant based in Bantva, a small town in the Indian state of Gujarat. While the rest of the family migrated to Pakistan in 1948, Arif’s father stayed behind to run the family business and sent money to take care of Arif and his siblings. In the early years, it was not much money, and as a result, Arif did not get much of an education, only ever passing 10th grade by the time he was 17. That year, 1970, was when his father sent enough money to his elder brother to buy a seat on the Karachi Stock Exchange (the value of which had plummeted as Pakistan was ravaged by the civil war that ultimately led to the creation of Bangladesh). Young Arif was recruited by his brother to start working there.

Arif excelled at the brokerage business, currying favour with the old men who dominated the exchange at the time. While nearly everyone there was literate, not all of them were comfortable reading, so Arif’s ability to read financial statements for his elders came in handy.

Throughout the 1990s, Arif Habib continued to focus on his brokerage business and gain influence at the exchange, though he was never really a truly wealthy individual back then. He got his big break in May 1998, when India conducted five nuclear tests, prompting Pakistan to follow suit. The threat of Western sanctions caused the Pakistani equity market to crash. Between May 8, 1998 – the last trading day before India conducted its tests – and July 14, 1998, the KSE-100 Index fell by 50.7%, losing more than half of its value in just over two months.

To add to the financial panic, the government had frozen all foreign currency accounts, which at the time accounted for nearly half of all bank deposits in Pakistan. Nobody was in the mood to buy.

Except Arif Habib.

He guessed, correctly, that once the political panic wore off, prices would rebound and anyone who had bought at the bottom would make a killing.

While everybody else was hoarding cash, Arif was buying everything he could get his hands on. Everyone, including his old cabal of friends, called him a madman.

But ultimately, he was proven right.

Within a year, the market was up 47%, and within two years, it had doubled, regaining its pre-nuclear test levels. Arif’s nerve paid off. Within a few years, he had gone from being just one of the many brokers on the exchange to being one of its wealthiest members.

Flush with the new-found wealth, Arif began expanding his financial services empire. In 2000, he set up the country’s second private sector asset management company (JS set up the first one in 1996). And in 2005, confident with his spate of recent successes, and cozy in his relationship with then-Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz, Arif bought himself a bank. Rupali Bank of Bangladesh (which itself was created with the seized operations of pre-1971 Pakistani banks) was shutting down its operations in Pakistan and Arif decided to buy them up, creating Arif Habib Bank.

That year was probably Arif’s best. His financial empire was expanding, he had begun construction on a massive new headquarters building on Queens Road in Karachi’s financial district, and was on the verge of building himself an industrial empire as well, by buying out the state-owned Pakistan Steel Mills.

In hindsight, however, it was also the beginning of the end of his charmed run. In 2006, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ruled that his acquisition of Pakistan Steel was illegal. And his bank was not off to a great start either. Brilliant though he was in the equity markets, Arif knew nothing of fixed income and did not appear to have hired people who did know. The result was a predictable calamity, with more than a quarter of loans ever given out by Arif Habib Bank eventually written off as bad debts.

Unlike the Shirazis, who seem to have dispassionately disposed of their bank, Arif took the failure of his ability to run a bank personally. In late 2008, he suffered a heart attack. The cause was never disclosed, but the stress from the losses of 2008 cannot possibly have been easy.

In October 2008, while the Shirazis were negotiating with KASB Group, Arif reached an agreement with Suroor Investments to sell his stake in the bank named after him. The transaction closed at Rs9.00 per share, or 0.77x the bank’s book value at the time.

Mybank

The third predecessor institution to Summit Bank was Mybank, which started its life in 1992 as Bolan Bank, created as the state-owned bank established by the government of Balochistan. You can guess how this baby never really had a chance.

But Iqbal Ali Mohammad wanted to give it a try. Iqbal was the CEO and one of the major shareholders of Gul Ahmed Textiles, arguably one of the best-known brands in Pakistani clothing.

By 2005, Gul Ahmed was one of the top five textile companies in Pakistan and one of its leading exporters, in addition to becoming a household name in Pakistan’s domestic women’s clothing market. Naturally, somebody in the family had the idea to buy a bank.

Iqbal took charge of this mission, buying out Bolan Bank in 2005 and renaming it Mybank. It is not immediately clear what exactly Iqbal or his brother had in mind when they bought the bank, because they do not seem to have done much with it.

By the time the bank was sold to Suroor Investments, in what can now be described as a mercy killing, more than 38% of all loans it had ever underwritten had to be classified as bad loans, unrecoverable and gone for good. Miraculously, the family managed to hold out until October 2009 before selling their shares in the bank for Rs8.00 per share, or 0.73x its book value at the time.

Mybank was the last acquisition completed by Suroor Investments before they created Summit Bank, the theory being that all of these banks were really crappy separately, but maybe together somehow they would be awesome. It was not an unreasonable theory, and the man who came up with it certainly had reason to hope it was true.

Inheriting the sausage

When you have a sausage in your hands, the best you can do is hope for a really good hot dog. Lawai knew he was not inheriting the best bank in the country, and he knew he had to craft a strategy for improving its operations because Summit Bank was losing money hand over fist. The bank he inherited was hemorrhaging money to the tune to Rs3 billion ($35.9 million) a year during his first year as a CEO, on a balance sheet of Rs72 billion ($853 million).

For the bank succeed in the segment of the market he wanted to, he first had to physically move the branches to where his prospective customers were. Of the 160 branches he inherited, in his first two years, Lawai had 47 of them moved. This, of course, had the effect of increasing his cost base for those years. In 2010, the bank was spending Rs40 million per branch, a number that came down to Rs26 million per branch by 2013.

In addition to the inherited branches, in the first two years he also added another 26 branches, taking the number up to 186. However, he appears to have realized soon enough that trying to grow the bank too fast, without having fully stabilized it, was probably not a good idea and since then, the bank has only added seven more branches.

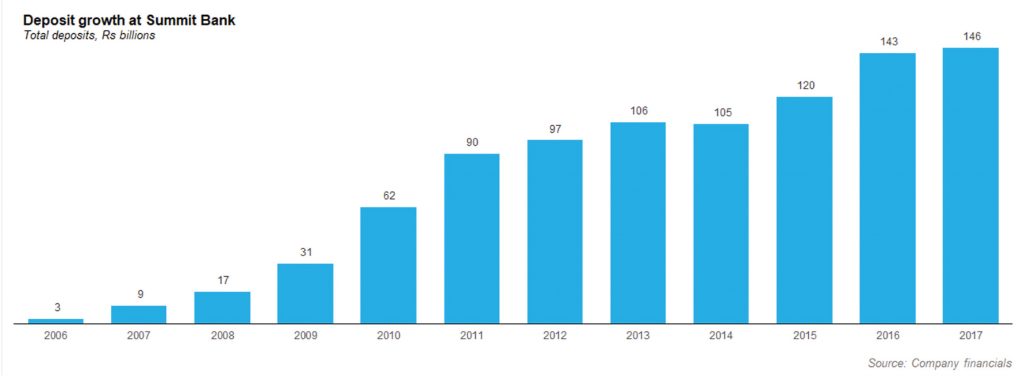

On the liability side, Lawai struggled with a critical problem: he effectively had hardly any retail deposits, only high-cost corporate ones (in 2009, the bank’s percentage of retail deposits was actually close to 0%). This resulted in a cost of deposits of 14.5%, the highest in the industry by a long shot. So another order of business was to unwind those costly long-term deposits and get cheaper ones in their place.

The branch relocation helped with at least some new deposits, but Lawai had to do more. And so, in order to attract retail deposits, Summit Bank went nuts, formulating a three-pronged strategy: staying open later in the evenings than their competitors and on weekends, introducing co-branded and prepaid debit cards (then still unusual in Pakistan), and focusing on the remittances business.

In areas of Karachi and Lahore with high net-worth depositors, the bank kept branches open till 8 pm. At the fanciest mall in Karachi, the branch stayed open till 11 pm, basically until the mall itself closed, to attract the accounts of the shops located there. And at the Fish Harbour in Karachi, the branch stays open 24/7. And 77 of its 193 branches stay open on Saturdays and two on Sundays.

The bank also introduced a prepaid debit card and co-branded some of its debit cards with some of the best-known consumer brands in Pakistan.

And in order to ensure that it gets truly retail deposits, Summit Bank focuses heavily on the remittances business. Despite being only the 17th largest bank in Pakistan by assets, it is the seventh largest in terms of handling inward-bound remittances to Pakistan. While the fee income on remittances is nice to have, the real advantage of the remittance business is having the deposit accounts of the families of expatriate Pakistanis, who tend to be slightly better off than similar families in any given geographic region.

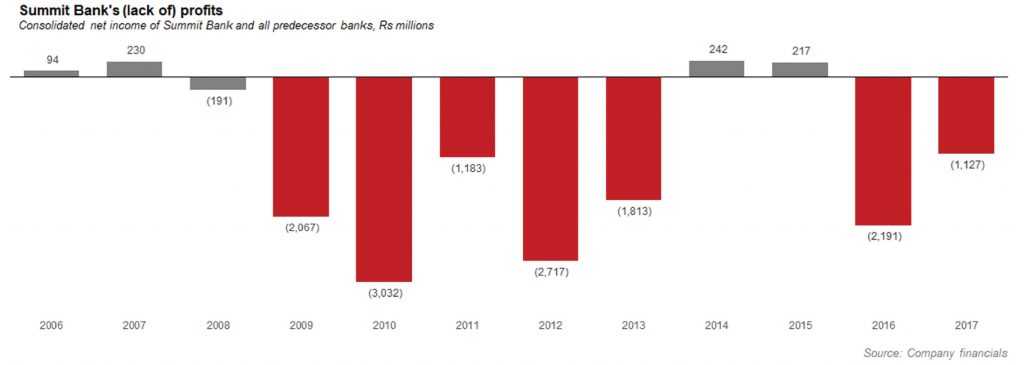

It was a valiant effort, but clearly not enough to build a viable bank. Lawai was able to eke out two years of profitability for Summit Bank – in 2014 and 2015 – which was enough for him to declare victory and retire to the life of an emeritus presence in Pakistani finance. Summit Bank continues to struggle with massive losses in both 2016 and 2017 – Rs2.2 billion and Rs1.1 billion respectively, and the year 2018 is not off to a much better start either, with a loss of Rs328 million in the first quarter.

The second fall

It appears, however, that history repeats itself, and the past continues to haunt Husain Lawai. Having gone into a semi-retirement, Lawai was taking on board positions across corporate Pakistan, including the prestigious appointment of becoming chairman of the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Once again, however, Asif Ali Zardari is in political trouble, and once again, Husain Lawai appears to be part of the collateral damage. Earlier this month, allegations of money laundering by leading political figures surfaced in an explosive investigative report in The News. Soon afterwards, Lawai confirmed to that newspaper that he had been prevented from leaving the country and was under investigation – once again – for assisting money laundering.

Lawai was acquitted on those charges in the past, and it is possible he is still innocent of these allegations now. But once again, Pakistan’s financial services sector watches as the once-high-flying CEO faces yet another fall from grace.

And this time, there may be no more room for a comeback.

Note by Editor: An earlier version of this article had claimed that the Nishat Group had won the bid for MCB bank in 1991 and Mian Mohammad Mansha had come to know Hussain Lawai during its privatisation process.

Clarification by MCB Bank: The bid document for the privatization of Muslim Commercial Bank Limited was submitted in the name of “Abdullah & others” comprising of 12 renowned industrialists (1. Mr. Mohammad Abdullah c/o Sapphire Textile Mills Ltd., 2. Mr. S. M. Muneer c/o M/s S. Mohammad Din, 3. Mr. S. S. Saleem c/o M/s Universal Leather & Footwear Industries Ltd., 4. Mian Mohammad Mansha c/o Nishat Mills Ltd., 5. Mr. Hajee Bashir Ahmad c/o Sitara Textile Mills. Ltd., 6. Mr. Tariq Rafi c/o Siddique Sons industries (Pvt) Ltd., 7. Mr. Mohammad Naseem c/o Mohammad Shafi Tanneries, 8. Mr. Mohammad Arshad c/o Arshad Textile (Pvt.) Ltd., 9. Mr. Sheikh Mukhtar Ahmed c/o Ibrahim Textile Mills Ltd., 10. Mr. Saqib Ellahi c/o Be Be Jan Pakistan(Pvt.) Ltd., 11. Mr. Bashir Jan Mohammad c/o F&B Bulk Storage (Pvt.) Ltd. and 12. Mr. Khawaja Mohammad Jaweed c/o Kohinoor Spinning Mills). The bid was approved in the name of “Abdullah & Others” which was later on renamed as “National Group”. Mr. Mansha knew Hussain Lawai as Country Manager Faysal Islamic Bank of Bahrain before the privatization of Muslim Commercial Bank Limited in his capacity as a Banker. Once the Bank was privatized the National Group assumed management control and Lawai became CEO of Muslim Commercial Bank Limited.

Great, informative article. Well done to the author for correctly presenting the facts.

Brilliant write-up

I have seen during last several years, that instead of watching the country interest all legal and financial experts whether Naik,Eitzaz ,Lawaee or who ever invariably have battled to save the looters and even assisted them in furthering their political and financial interest through their witty and cunning tactics.The one associated factor is the week prosecution from govt. Side because the prosecution lacks the protection from big guns.The glaring example are murder of Inspector Yakoob in case of Murtza Bhutto and in recent past the brazen murder of custom inspector who caused the Arrest Of Ayaan.we all feel the pain and disgust of all such atrocities but are silient spectators.my passionate appeal is the protectors whether in guise of law of Finance that they will also held guilty before ALLAH for patronising the crime.please take pity on yourself before the day of judgement comes, which they certainly have to face.

Mr Lawai was Country General Manager of Massraf Faysal Al Islami Al Bahrain, Present Faysal Bank Ltd. On his orders Bank Gurantee of Rs 890 million issued in favor of Privatization Commission to buy out MCB without any MARGIN or Security from applicant National Group..Later Bank Gurantee was bounce back and State Bank of Pakistan debit the amount from MFIB the first Islamic Bank in Pakistan been established with great efforts by Prince Mihammad Al Faysal on the request of General Ziaul Haq. Mr Hadi Ali Khan and Mr Qazi signed the guarsntee. While guarantee was in progress The CEO of Bank Mr Nabil Nassif and General Manager Imtiaz Pervez were present in adjacent room. Later they accuse Mr Lawai of this violation but in fact they were accomidated. Mr Qazi was victimize and force to leave the bank and Mr Hadi Ali Khan and Mr Saleem Qureshi were tsken to MCB on prestigious jobs as SEVP and SVP respectively.

This is the story that has mysteries, myths and fact that could shake the entire bankimg practice of lending against bank guarantee.

We are some who know all what happen and because of such information I have to leave the bank who was the only academic qualified Islamic Banker in Pakistan joined MFIB in 1982 with degree in Islamic Banking. I served the bank 14 years and been founder member forced to resigned. Think to umearth the realities but remain quite. Mr Lawai started rising from MFIB in October 1987 to reach Adyala in 2018. Diring the period is a myth?

Journey to Adiala jail started in October 1987! There must be much more against him than a bank guarantee of mere Rs.890 million which have caused the law enforcers to act so aggressively against him. His over a decade long going in exile too shed volumes bringing bad name to country. Proper course to deal with economic and financial crimes being committed against nation and country is to charge miscreants under the treason laws with award of capital punishment and confiscation of all assets by the state. Only than things would be controlled. Sooner the better to extricate the country from the morass of despondency and from near to disastrous situation.

I like the way Profit articles are written. Extensive details, up to the mark language.

Having worked for Summit Bank, I can safely say that the Bank’s culture & systems were never competent and competitive. It has one of the highest employee turnover due to having probably the most underpaid staff for its qualification. While Mr. Lawai was a bully with the top management. The RGMs too were good for nothing.

Overall, I realised that the bank served a specific purpose for specific people. It was never inclined towards growth & success. And it’s plan to convert wholly into Islamic banking fell on its face.

The whole purpose of Summit Bank was to be involved in illegal money transfers for big shots

If Mr. Lawai has so much of reputational baggage, why was he (s)elected as the PSX Chairman? Was SECP asleep? Also, he is on the boards of a number of MNCs like GSK — do they not care about ethics and reputational risk? He is also the CEO of IBP — couldn’t SBP find a better person to head this institute than Mr. Lawai?

Further, this time round, IBP’s powers-that-be must have a transparent selection process for the CEO rather than taking a decision in a “club” style and the SBP Governor just rubber stamping it!

Comments are closed.