Drive down the old Victoria Road (now called Abdullah Haroon Road) in Karachi towards Saddar, about one kilometer down from Frere Hall, and you will get to a place that used to be called Victoria Market in the colonial era (and now has no real name), the kind of bazaar that would be commonly found in just about any part of Pakistan, with many small shopkeepers selling their wares – clothes, sporting goods, etc. – to lower middle class retail consumers who walk by.

Here, in a building labelled International Business and Shopping Center, is the ostensible global headquarters of a business that has billions of rupees in annual cash flow, and dealings with some of the largest businesses and political figures in Pakistan and the Middle East. It is called A-One International, and it is owned by a man named Tariq Sultan.

At least that is what the official bank documents say.

Tariq Sultan is no billionaire. He does not know any politicians or wealthy businessmen. He has absolutely no connection to the Rs4.5 billion worth of transactions that have allegedly taken place in his name. He is the victim of the kind of identity theft that takes place in Pakistan’s banking sector every day: his computerised national identity card (CNIC) has been used to create a benami (anonymous) account.

Benami accounts are commonly used in money laundering, and are illegal, but are such a common practice in Pakistani banks that many banks even have under-the-table procedures for how to handle them, often keeping forms that instruct branch employees to ignore the difference in the signature of the person who actually operates the bank account and the signature on the CNIC of the person whose identity is being stolen.

Sultan’s case, in other words, is more common than it looks. What makes his case unique, however, is the fact that the people using his identity to allegedly conduct these money laundering transactions are people who sit at the nexus of money and political power in Pakistan, and more specifically, in Sindh. And the account in Sultan’s name involves payments between parties who are about to engage in the largest bank merger in Pakistan this year.

The Sindh Bank merger with Summit Bank

In November 2016, the provincial government-owned Sindh Bank announced that its board of directors had decided to begin the process of merging the bank with Summit Bank, itself an amalgamation of three slapdash mergers that took place between 2009 and 2011.

The merger makes a certain amount of sense from the perspective of Summit Bank: Sindh Bank is a bank that has a large branch network, a steady and growing deposit base, and surprisingly healthy profitability considering the fact that it is a state-owned bank and most government-owned banks in Pakistan tend to be financial basket cases.

However, from the reporting around the issue, it seems somewhat clear that the acquiring entity is Sindh Bank, and why they might want to acquire Summit Bank is less clear, other than the fact that Summit may be the only bank that Sindh Bank can afford to buy. Sindh Bank may be profitable, but it is still one of the smallest banks in the country.

What is astonishing about this turn of events is that, in 2010, when Sindh Bank was conceived and about to be launched, nobody could have anticipated this turn of events.

The story of Sindh Bank

In later 2010, almost every provincial government had established a bank. The government of Punjab was the majority owner of the Bank of Punjab, which it had created in 1989. The government of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa had created the Bank of Khyber in 1991. Even the government of Balochistan, Pakistan’s poorest province and smallest by population, had created its own bank, Bolan Bank, in 1992, which it then sold off in 2005. The bank was later renamed Mybank.

Ironically, the provincial government whose capital city is also the financial capital of the country and therefore chockful of financial talent was the one government that had not yet created its own bank. And so, in 2010, two years into the Pakistan Peoples Party’s (PPP) return to office in Sindh, the provincial government in Karachi undertook the task of creating its own bank.

Fairly or not, the PPP-led government in Sindh has a reputation for being corrupt even by Pakistani provincial government standards, and so when they submitted an application for a banking licence to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), there was an informal betting pool among a certain segment of the SBP staff as to when this new bank would require its first bailout. The longest anyone was willing to bet it could last without a bailout was five years.

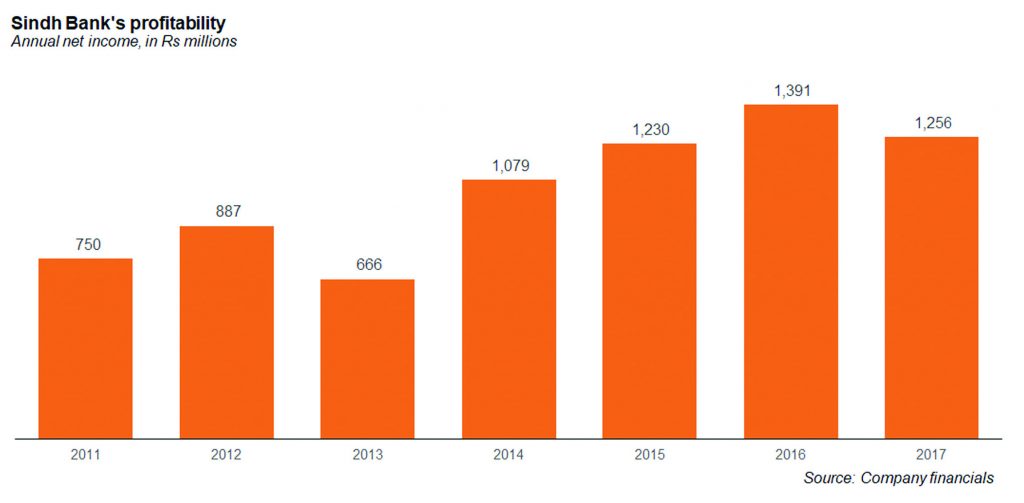

But, so far,, Sindh Bank appears to have confounded the sceptics. The bank has been profitable for every one of the seven full years it has been in existence and while its non-performing loan ratio (proportion of the total lending book that has defaulted on their loans) is high by international standards at 8.1% as of June 30, 2018, that number is positively respectable by Pakistani standards.

This is despite the fact that the bank has gone on a very rapid expansion drive and currently has 300 branches, and also owns its own microfinance bank.

Of course, it helps that nearly 60% of the bank’s Rs122 billion deposit base comes from the provincial government and that it deploys most of those deposits into federal government bonds. Nonetheless, the bank does have a Rs75 billion loan book, and of that, over 83.3% goes towards private sector borrowers.

It is, of course, theoretically possible that Sindh Bank is able to hide its losses (most banks around the world can hide their losses quite easily if they choose to do so), though we have no reason to believe that they have done do. But the profitability numbers look better than one might expect from a state-owned bank. For the twelve months ending June 30, 2018, the bank had a net income of Rs1,046 million. This represents a decline of 32.7% over the same period in the previous year, but is at least still a positive number instead of a loss. The return on equity (ROE), the key measure of bank profitability, however, was a paltry 6.3% compared to the robust double-digit ROE figures enjoyed by most larger banks in Pakistan.

Summit Bank: the sausage limps on

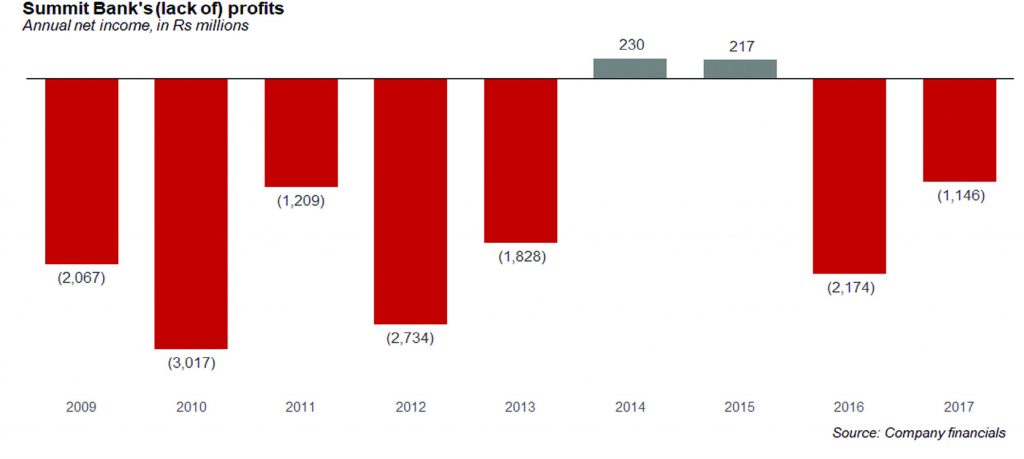

Yet even if Sindh Bank’s profitability numbers are somewhat below the Pakistani median, Summit Bank is doing significantly worse. In the nine years that it has been in existence, Summit Bank has posted a profit in precisely two years and has otherwise continued to hemorrhage money. For the twelve months ending March 31, 2018, the latest period for which financial data is available, Summit Bank had net losses of Rs1,359 million. Try as it might Summit Bank has just not been able to make money.

The reason, of course is that Summit Bank was always something of an orphanage for banks in Pakistan, having acquired what were previously the three smallest banks in the country that were effectively abandoned and left for dead by their previous owners: Arif Habib Bank (2009), Atlas Bank (2010), and Mybank (2011). None of those three banks was ever a viable bank on its own, and while the theory was that they might be more economically sustainable when put together, so far that hypothesis does not appear to be true.

The lack of profitability is not for a lack of trying. The founding CEO of the bank, Husain Lawai, made a valiant effort to make the bank profitable, undertaking several initiatives to improve the bank’s operations.

Of the 160 branches he inherited, in his first two years, Lawai had 47 of them moved. This, of course, had the effect of increasing his cost base for those years. In 2010, the bank was spending Rs40 million per branch, a number that came down to Rs26 million per branch by 2013.

In addition to the inherited branches, in the first two years he also added another 26 branches, taking the number up to 186. However, he appears to have realized soon enough that trying to grow the bank too fast, without having fully stabilized it, was probably not a good idea and since then, the bank has only added seven more branches.

On the liability side, Lawai struggled with a critical problem: he effectively had hardly any retail deposits, only high-cost corporate ones (in 2009, the bank’s percentage of retail deposits was actually close to 0%). This resulted in a cost of deposits of 14.5%, the highest in the industry by a long shot. So another order of business was to unwind those costly long-term deposits and get cheaper ones in their place.

The branch relocation helped with at least some new deposits, but Lawai had to do more. And so, in order to attract retail deposits, Summit Bank went nuts, formulating a three-pronged strategy: staying open later in the evenings than their competitors and on weekends, introducing co-branded and prepaid debit cards (then still unusual in Pakistan), and focusing on the remittances business.

In areas of Karachi and Lahore with high net-worth depositors, the bank kept branches open till 8 pm. At the fanciest mall in Karachi, the branch stayed open till 11 pm, basically until the mall itself closed, to attract the accounts of the shops located there. And at the Fish Harbour in Karachi, the branch stays open 24/7. And 77 of its 193 branches stay open on Saturdays and two on Sundays.

The bank also introduced a prepaid debit card and co-branded some of its debit cards with some of the best-known consumer brands in Pakistan.

And in order to ensure that it gets truly retail deposits, Summit Bank focuses heavily on the remittances business. Despite being only the 17th largest bank in Pakistan by assets, it is the seventh largest in terms of handling inward-bound remittances to Pakistan. While the fee income on remittances is nice to have, the real advantage of the remittance business is having the deposit accounts of the families of expatriate Pakistanis, who tend to be slightly better off than similar families in any given geographic region.

It was a valiant effort, but clearly not enough to build a viable bank. Lawai was able to eke out two years of profitability for Summit Bank – in 2014 and 2015 – which was enough for him to declare victory and retire to the life of an emeritus presence in Pakistani finance. Summit Bank continues to struggle with massive losses in both 2016 and 2017 – Rs2.2 billion and Rs1.1 billion respectively, and the year 2018 is not off to a much better start either, with a loss of Rs328 million in the first quarter.

A home for money laundering?

So what does the merger of these two banks – struggling to varying degrees – have with the identity theft mentioned at the beginning of our story?

Well, the account in Tariq Sultan’s name is one of 29 allegedly fake accounts that are being investigated by the Federal Investigation Agency’s (FIA) State Bank Circle, the division of the country’s premier law enforcement agency that is responsible for investigating financial crimes. The FIA alleges that these accounts are being used for money laundering and illicit payments between politically connected businessmen and high-ranking politicians, including former President Asif Ali Zardari, and his sister Faryal Talpur, a current member of the Sindh Assembly and widely regarded as the de facto Chief Minister of Sindh.

The FIA’s investigation report – made available to Profit – reveals a pattern of flouting the law against money laundering on the part of Summit Bank employees, who appeared to be operating under direct orders from Husain Lawai, who served as CEO of the bank from 2009 through the beginning of 2016. Lawai and Zardari are old friends, and Lawai spent a considerable portion of the 1990s and 2000s in exile, fighting charges of money laundering on behalf of Zardari. He was exonerated of those charges in the UAE in 2002 and the charges against him in Pakistan were dropped in 2008.

But if the FIA’s version of events is accurate – and they have assembled considerable evidence that it may well be – it appears that Lawai is not done helping Zardari flaunt the law with respect to money laundering.

The account in Tariq Sultan’s name, for instance, was operated by another person entirely (and one not identified by name in the FIA’s charges), and was used to receive and make billions of rupees in payments to large businesses as well as well-connected individuals.

Here is how it worked: the person operating the account in Tariq Sultan’s name would come and conduct transactions with the operations manager at the DHA Khayaban-e-Tanzeem branch of Summit Bank in Karachi. The operations manager would then pass on the documents as being verified to the relationship manager, who would then clear them and forward them to the branch manager. The branch manager, knowing that the operations department of the bank may catch the forged signatures, would write on the documents “Referred by Husain Lawai” so as to let the bank’s staff know that the scheme was cleared by the CEO himself, and that any forgeries should not be questioned.

The use of the DHA Khayaban-e-Tanzeem branch is interesting in itself. For those unfamiliar with Karachi’s geography, this branch is 6.2 kilometers away from the market in which the business that owned the account supposedly resides. What makes it even more suspicious is that there is a Summit Bank branch on Elphinstone Street (now called Zaibunnisa Street) less than a 3-minute walk away from the shop in Victoria Market. Why on earth would a busy shopkeeper go to a branch so far away when there was one virtually next door?

Incidentally, the bank maintained documents in its “know your customer” (KYC) records that indicated that they knew that the account for A-One International did not really belong to Tariq Sultan, but rather to the Omni Group, a sugar and real estate conglomerate supposedly owned by Anwar Majeed, a close associate of Zardari and widely suspected to be a businessman who acts as the front for the former president’s commercial interests.

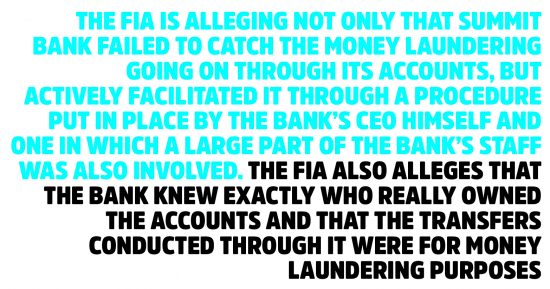

In other words, the FIA is alleging not only that Summit Bank failed to catch the money laundering going on through its accounts, but actively facilitated it through a procedure put in place by the bank’s CEO himself and one in which a large part of the bank’s staff was also involved. The FIA also alleges that the bank knew exactly who really owned the accounts and that the transfers conducted through it were for money laundering purposes.

So why would the bank facilitate this? The FIA alleges – with some evidence – that bank’s majority shareholder, Nasser Abdulla Hussain Lootah, a member of one of the oldest and wealthiest families in Dubai, may have been a beneficiary of the money laundering himself.

Whose money flowed through the accounts

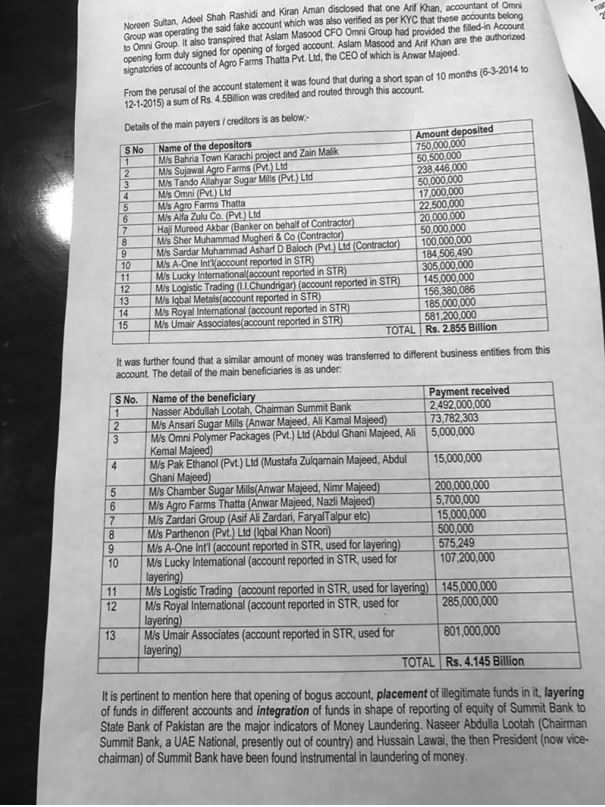

The FIA offers very detailed descriptions of exactly who received how much money from the accounts. For instance, in the case of the A-One International account, the FIA alleges that a series of transactions took place in the 10 months between June 3, 2014 and December 1, 2015 that involved up to Rs2,855 million entering the account and Rs4,145 million leaving the account.

The list of who sent money and who received it is also fascinating. There was, for instance, Rs750 million received from Bahria Town Karachi, the massive new suburb being built by real estate magnate Malik Riaz Hussain. There are several hundred million rupees received from sugar mills known to be owned by the Omni Group and Anwar Majeed.

The payments are particularly fascinating as well, such as the Rs2,492 million paid out to Nasser Lootah and several million rupees paid out again to companies controlled by Anwar Majeed, and one company directly owned by Asif Zardari and Faryal Talpur (Zardari Group).

Who owns the bank?

The payment to Lootah in particular is interesting. The amount represents a sizeable amount of money being paid to the owner of the bank itself and raises several questions as to what the transaction was about and why it was conducted in such a suspicious manner.

There have been rumours circulating since the very beginning of the Zardari administration that something was off about the ownership structure of Summit Bank. The fact that it was owned by Lootah, who previously had no businesses in Pakistan and still does not list his ownership of Summit Bank on his own group’s website, was seen as suspicious, raising questions that Lootah was perhaps acting on behalf of an undisclosed third party. That undisclosed third party was often speculated to be Asif Ali Zardari, though no hard evidence of his ownership of the bank ever emerged.

Those rumours are lent some degree of credence by the money laundering investigation by the FIA, which appears to have caught vast sums of money flowing back to Lootah, almost as though they were payback for having put up the money to buy the bank and shore up its capital reserves to the levels required under the law by the State Bank of Pakistan.

The A-One account, for instance, is just the tip of the iceberg. The FIA is investigating 28 other accounts, which saw suspicious transactions worth a total of Rs35 billion to various entities. Of the total of 29 accounts, 16 were at Summit Bank, eight were at Sindh Bank, and five at United Bank.

A total of seven people’s identities were used to open these accounts, which the FIA believes were mostly fraudulent. Of the seven people who have been issued subpoenas, only three have responded, said FIA Director General Bashir Memon in a hearing at the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Meanwhile, in connection with the investigation, the FIA is currently prosecuting Husain Lawai, Taha Raza, former head of corporate banking at Summit Bank, Anwar Majeed and his son Abdul Ghani Majeed, as well as former President Zardari and Faryal Talpur. The latter two were able to post bail and are thus not in jail during the ongoing investigation.

If the merger between the two banks were to go through, the owners of Summit Bank, whether it be Lootah or someone else, will become shareholders in Sindh Bank, a bank that will remain majority owned and controlled by the Sindh government.

One can see why a person who has strong political influence over the Sindh government currently and expects to retain that control over the next several years would be in favour of such a merger. And one can see why there may be questions as to whether such a merger is appropriate, which is where the Supreme Court’s investigation on the matter comes in.

The Supreme Court’s role

The FIA investigation was completely separate from the litigation surrounding the announced merger between Summit Bank and Sindh Bank, though it surfaced during the course of the suo motu hearings that took place in the court about the matter.

The court was investigating the matter after allegations surfaced that the merger may not be above board and since it involved public money in the form of the Sindh Bank’s ownership, the apex court decided to look into the merger. It was during those hearings that the FIA’s four-year -long ongoing investigation of money laundering came to light.

Meanwhile, the boards of directors at both banks appear to be moving ahead as though nothing has happened. They have both approved the all-equity merger, which will see a share swap ratio of 8.37 to one, where Summit Bank’s shareholders will receive 1 share of Sindh Bank for each 8.37 shares of Summit Bank that they own. The merger is still subject to final approval both by the a meeting of the shareholders of Summit Bank as well as the Supreme Court, which has yet to issue a final ruling on the matter.

The court, however, does not appear to be in the mood to let the case go. On September 5, it ordered the creation of a joint investigation team (JIT) to investigate these allegations, which may well drag out the case even longer, and may well result in the merger not being approved.

The banks’ responses

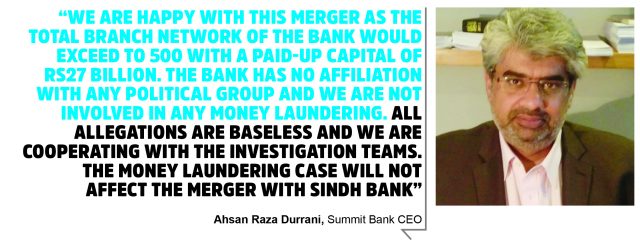

Summit Bank CEO Ahsan Raza Durrani said: “We are happy with this merger as the total branch network of the bank would exceed to 500 with a paid-up capital of Rs27 billion.” He went on to add: “The bank has no affiliation with any political group and we are not involved in any money laundering. All allegations are baseless and we are cooperating with the investigation teams. The money laundering case will not affect the merger with Sindh Bank.”

Bilal Sheikh, the former CEO of Sindh Bank, said: “After merging Summit Bank with the Sindh Bank, the Sindh government may further enhance its investment of Rs 10 billion in the bank.”

He added: “The Supreme Court never opposed the merger of the banks, but it asked us why we are merging Summit Bank with it. We replied to the SCP that after this merger Sindh Bank will be listed on stock market, we will have over 500 branches network and will have other businesses like Summit Bank.”

“After completing necessary regulatory work, we will have to take final approval from the Supreme Court and Inshallah we will get it before September 30,” he claimed. “The merger process would be completed by the end of 2018 and we will also issue the initial public offering [IPO] of Sindh Bank before the end of 2018.”

Where the investigation goes next

As may be evident from the CEOs’ statements, the banks themselves do not appear to see the Supreme Court investigation as being a significant hurdle in completing the merger. And there are some within the FIA who believe that optimism may well be warranted.

One FIA source familiar with the investigation told Profit: “This money laundering investigation was being used to rein in the Pakistan Peoples Party in the run up to the 2018 election. Now that the election is over, the case will be shut down again.”

Great article!

Mr. Lootah…. true to his name, just like Mr. Zardari!

How someone with this surname even passed the KYC – Know your customer?

Comments are closed.