Once a digital phenomenon, an online buzzword, and a place where students competed for the number of friends they had, Facebook appears to have been undertaken by competitor social media platforms such as Snapchat and Facebook-owned Instagram and Whatsapp. Research says that these platforms are more popular with younger internet users, a demographic once dominated by Facebook.

Where did Facebook go wrong? It’s a combination of what experts have called “hypergrowth”, unpopular product enhancements and bad publicity in the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. From the recent data privacy scandal to the infighting between senior executives in the company which plummeted investor confidence, Facebook is in dire need of an image overhaul.

Has Facebook become too large?

Seeing Facebook’s growth, it seems as if everyone is a user. Indeed, Facebook reported a total of 2.2 billion global users by the end of March 2018. This might be both a blessing and a curse for Facebook: when you ask teenagers why they use Instagram or Snapchat more than they use Facebook, their answer is usually the same – “Our parents are on Facebook, and maybe even our grandparents. We don’t want them to see what we post.”

Facebook remains extremely popular in Pakistan, where 44.6 million people are connected to the internet through mobile phones and/or computers. Of these, 35 million people use Facebook according to the Global Digital report prepared by We Are Social and Hootsuite that was released in April 2018.

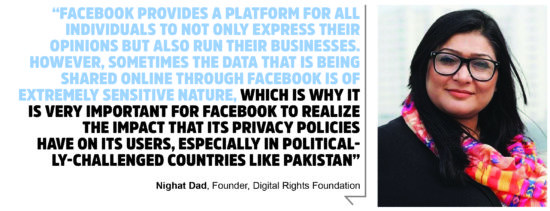

“Facebook is an integral part of not just our day-to-day lives but also e-commerce,” says digital rights activist Nighat Dad who founded the Lahore-based non-profit organization Digital Rights Foundation.

Product enhancements that need work

The year 2004 witnessed the birth of Facebook from the glorified halls of Harvard University. Two years later, the company launched a feature called the ‘News Feed’, which presented information collected from a user’s friends list in a single window. The feature, now considered extremely popular with Facebook users, shocked the platform’s users at that time who felt that it was a violation of their privacy. Founder Mark Zuckerberg issued an apology, saying, “We really messed this one up. We did a bad job of explaining what the new features were and an even worse job at giving [users] control of them.”

Facebook had barely gotten over this hump when one year later in 2007, it launched “Beacon” with 44 partner websites. Beacon, which became a fundamental part of the company’s advertising system, sends data from external websites to Facebook to allow targeted advertisements. It also allows users to share their activities with connections.

Beacon would report to Facebook on its members’ activities on third-party sites which were also participating with Beacon. These activities would be published to users’ News Feed. This would occur even when users were not connected to Facebook and would happen without the knowledge of the Facebook user.

One of the main concerns was that Beacon did not give the user the option to block the information from being sent to Facebook. When word got out and this feature became public knowledge, Zuckerberg was again forced to apologise, this time saying, “We simply did a bad job with this release, and I apologise for it. People need to be able to explicitly choose what they share.”

Dad believes that this is a core problem that Facebook needs to tackle if it is to survive as a leading social media platform. “I don’t have any doubts about Facebook’s survival if they are more accountable and transparent to their users. Facebook needs to realize the huge responsibility it has towards its users and how data that is shared with them by the users is on the basis of trust,” she stresses. “The world was shocked when the Cambridge Analytica scandal happened and have still not really grasped the consequences of it. But this is the best time for Facebook to work on its data protection policies and ensure that their users’ privacy is not compromised.”

When asked how aware the Pakistani population is regarding its online rights and digital security, Dad said Pakistanis have not yet realized the impact of how their data can be used against them. “We are just beginning to realize its impact by seeing very extreme cases of online violence in recent years,” she says. “Facebook provides a platform for all individuals to not only express their opinions but also run their businesses. However, sometimes the data that is being shared online through Facebook is of extremely sensitive nature, which is why it is very important for Facebook to realize the impact that its privacy policies have on its users, especially in politically-challenged countries like Pakistan.”

After revealing that Cambridge Analytica had received unauthorized data on up to 87 million Facebook members and that nearly all Facebook users may have had their public profile scraped, Zuckerberg said, “We’re an idealistic and optimistic company. But it’s clear now that we didn’t do enough. We didn’t focus enough on preventing abuse and thinking through how people could use these tools to do harm as well. We are going to do a full investigation of every app that had a large amount of people’s data”.

In the aftermath, shares plummeted; thousands deactivated their Facebook accounts, and the U.S. government got involved and eventually called Zuckerberg into a congressional committee hearing and demanded answers to questions everyone wanted to ask.

Can Zuckerberg use the hate to turn things around for the company?

Following increased scrutiny in the United States and Europe after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook has made efforts to improve its ads and content verification practices particularly around elections. Ahead of the 2018 General Election in Pakistan, Facebook published a blog post detailing the steps they had taken to detect and prevent what they called “abuse” of the platform. In particular, they addressed their targeted ads feature which had received significant criticism for exacerbating political polarization by showing users political ads that corresponded with their political views gleaned through data that users shared on their Facebook profiles.

If the internet is to be designed, operated, and governed in a way that protects and respects human rights, we must all play our part. Companies, governments, investors, civil society organisations, and individuals – as employees of companies, as citizens of nations, as consumers of products, and as users of a globally interconnected internet – must all take responsibility and act.

Corporate transparency and accountability are incomplete without transparent and accountable governments that fulfill their duty to protect human rights. Meanwhile, companies should be held responsible for all the ways that their products, services, and business operations affect user’s rights.

Governments, regulatory bodies, digital rights and consumer protection associations worldwide are trying to scrape out balanced policies that can allow tech companies to continue to operate, and guarantee greater or perhaps, ‘complete’ rights and access to users of their own information. Governments must impose stringent regulations on companies which fail to protect people’s data from cybercriminals. Companies must employ experts to stop any data breaches or hacks on their systems.

Users are often oblivious to the data being collected about them and what happens to this information. Providing personal data is a necessary evil for the convenience of accessing goods and services online. Consumers must automatically consent to requests for information and cannot always fully restrict the type of details that they hand over to advertisers and third-party websites. And when it comes to dealing with companies online, individuals are faced with the organisation’s privacy and the settings that it has determined.

Facebook needs a drastic change in the way people use it. It needs change of a significant magnitude that makes people want to try out the new Facebook, know that their online activity is safe, and that they can depend on Facebook to not share it with anyone without their explicit consent.