Habib Metropolitan Bank has one of the fastest growing deposit bases among middle market banks in Pakistan, a branch network that has been rapidly expanding beyond its Karachi base, the leading market position in trade finance, and is led by a CEO who has previously led Standard Chartered Pakistan and Barclays Pakistan.

One would expect Habib Metro to be thought of as among the most dynamic banks in the country. And while it certainly posts stellar numbers, the bank nonetheless has a reputation for being decidedly old-fashioned.

This is no accident: the reputation for being old-fashioned relationship-focused bankers is cultivated by design by the bank’s owners, and shapes virtually everything about the bank.

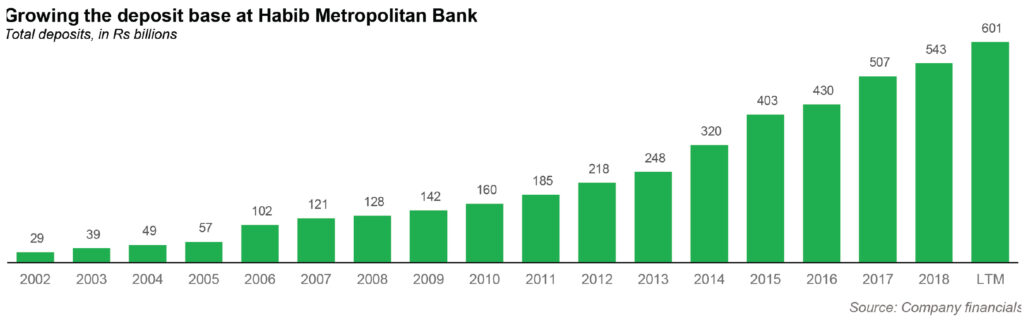

Habib Metropolitan is the smallest among the three “banks named Habib” in Pakistan, named after Habib Esmail, the founder of Habib Bank Ltd, the bank that is now the largest in the country. It is owned by the descendants of Habib’s third son, Mohammedali Habib (as opposed to Bank AL Habib, which is owned by the descendants of Mohammadali’s elder brother Dawood Habib). Its deposit growth over the past year (18.1%) is significantly higher than the market average of 7.6% for the 12 months ending September 30, 2019, the latest period for which complete financials are available.

Like most other banks, however, Habib Metro appears to do most of its lending to the government, plowing much of its deposit growth lazily into government bonds. What little money it does lend to the private sector is mostly in trade finance, where admittedly the bank has an outsize market share.

The problem with a bank so heavily reliant on (heavily collateralised) trade finance and government bonds? It ends up with a low appetite for credit risk, which may sound like a good thing until one considers the fact that managing credit risk is the entire point of the existence of a bank in the first place.

Check out our new feature – listen to the article:

History of the bank

Habib Metropolitan Bank started life in Pakistan as Metropolitan Bank in 1992, one year after the government of then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif decided to allow private sector players to re-enter the banking industry in Pakistan.

Consider the context at the time. In 1973, of the five largest banks in Pakistan, four were privately owned. By January 1, 1974, all five were state-owned, with the federal government nationalising the private banks in what was anything but a friendly transaction. The Habib family were among the biggest losers, having lost Habib Bank, which was then the largest private sector bank in the country.

That nationalisation drive was the result of the populist leftist government of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who came into office in 1972. He lasted until 1977, when he was overthrown in a military coup, led by General Ziaul Haq. In theory, Zia was more market friendly than Bhutto, but he liked state control a whole lot more so he never really reversed nationalization.

His immediate successor, Benazir Bhutto was not exactly much better than her father. It was not until Nawaz Sharif became prime minister in 1990 that the government began privatisation and deregulation.

The Habib family always had a greater share of their wealth abroad than the other Pakistani wealthy families. They owned banks in several countries around the world – mostly focused on trade finance – with the headquarters in Zurich, a bank known as Habib Bank AG Zurich.

That bank continued to operate in Pakistan as a foreign bank and was therefore left largely untouched. However, it was a tiny bank and at the time, foreign banks were under far more restrictions than they are today. So when, in 1991, the government allowed private sector players to enter the banking market again, the Habib family decided to try their luck again at a domestically incorporated bank.

The Dawood Habib branch of the family was first to take the plunge, incorporating Bank AL Habib in 1991, and the Mohammedali Habib branch of the family felt that there would be too much confusion if there were all of a sudden three banks named Habib and so they decided to name their bank Metropolitan Bank.

To lead the bank, they chose a veteran Pakistani banker named Kassim Parekh, the Bantva Memon gentleman who had originally joined Habib Bank in 1948 as a 17-year-old boy and had continued to rise through the ranks both in the Habib family and nationalised era to become president of Habib Bank in 1984, a position he retained until 1988. Soon afterwards, in September 1989, Parekh was appointed Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, where he served for just under a year.

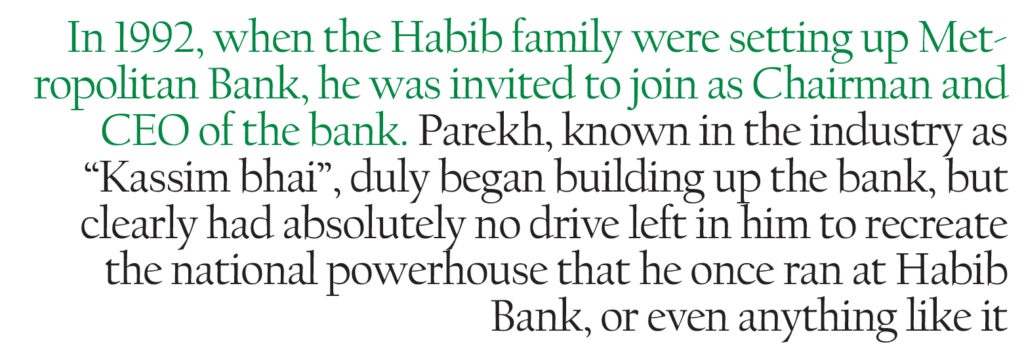

In 1992, when the Habib family were setting up Metropolitan Bank, he was invited to join as Chairman and CEO of the bank. Parekh, known in the industry as “Kassim bhai”, duly began building up the bank, but clearly had absolutely no drive left in him to recreate the national powerhouse that he once ran at Habib Bank, or even anything like it.

And why would he? After all, he took over Metropolitan Bank at the age of 61, having already worked for over 41 years, and having served as the president of then the second largest bank in the country as well as the first Memon to serve as the State Bank Governor. What could he possibly achieve at Metropolitan Bank that would be even a shadow of his existing achievements?

And so, he set about what sounds like one of the laziest growth strategies of any Pakistan bank still in existence. The branch network was heavily concentrated in Karachi, the country’s financial capital, and lending was focused entirely on trade finance (more on why that is lazy later). At the time he left the position of CEO (he remained chairman of the bank until June 2016) in April 2008, only 19% of the bank’s branches were outside Karachi and Lahore.

By 2006, the Mohammedali Habib side of the family had enough confidence in their brand name to realise that more banks named Habib would not necessarily be a problem in the Pakistani market. Consequently, they integrated the old Habib Bank AG Zurich’s Pakistan operations with Metropolitan Bank, and the combined entity came to be known as Habib Metropolitan Bank. Unlike other bank mergers in Pakistan, this one was not necessarily a big deal. No cultural issues or any other integration mess because really, it was basically one bank with two legal entities anyway.

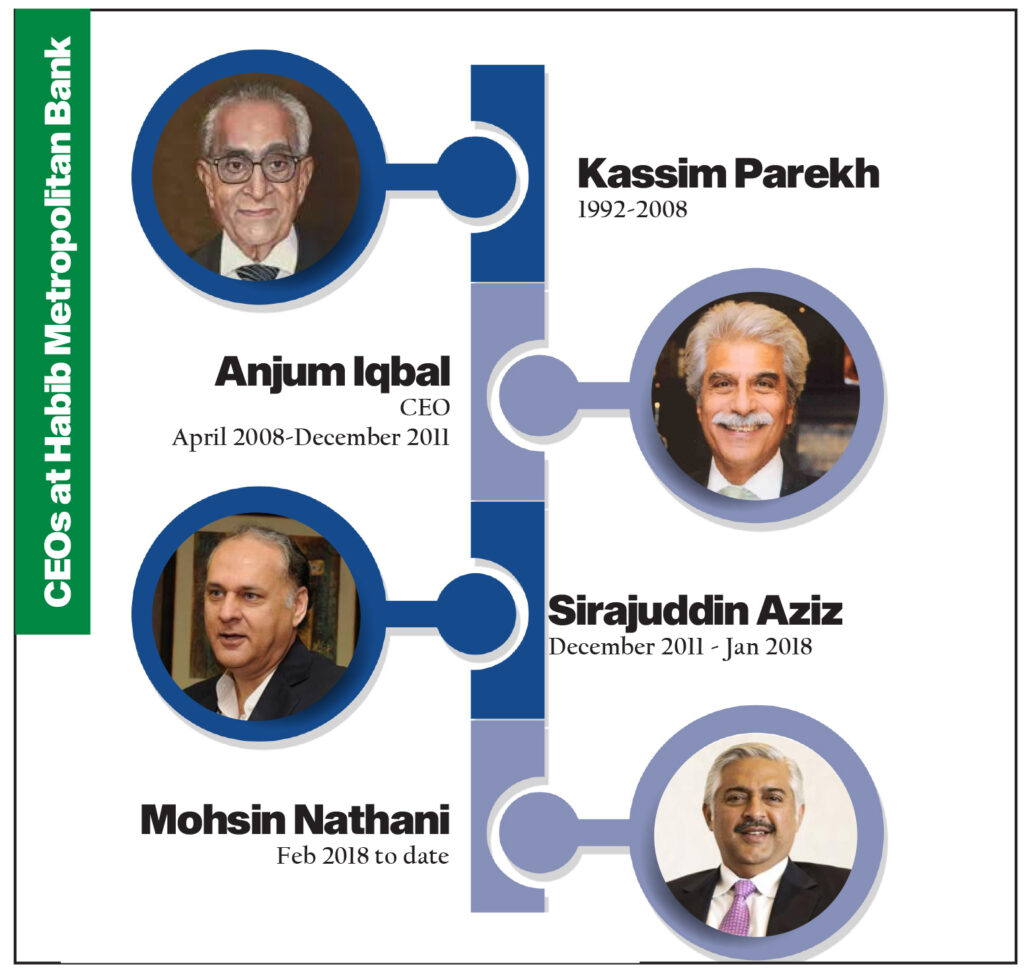

Parekh served as CEO for 16 years and finally decided to step down as CEO in April 2008, when he was replaced by Anjum Iqbal, a Citibank veteran.

The Anjum Iqbal years

Anjum Iqbal has the kind of resume that one would expect bank owners to drool over. He started off in Citibank’s Pakistan operations and quickly rose through the ranks. He headed Citi’s corporate bank in Pakistan, their investment bank in Turkey and Venezuela, before heading up their entire operations in Turkey and Africa. He then topped off his Citi career in London, leading emerging markets lending and all commercial lending in Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa.

But again, the Habib family made a mistake in choosing the man way too late in his career. Iqbal, a 1975 graduate of the Institution of Business Administration in Karachi (then Pakistan’s only real business school), had been working at Citi for more than 33 years when he was tapped to be CEO of Habib Metropolitan. Having lived a comfortable life in London for the last several years, did they really think he would have the stomach to take their bank through a turbulent democratic transition and the worst financial crisis in its history?

If they did, they were dead wrong.

Under Iqbal’s tenure, deposits grew at a rate of 9.5%, which sounds impressive until you realise that inflation during that period was running at about 15.4% on average, and even the banking industry as a whole grew by 13.7% per year on average.

He lasted barely three and a half years on the job and his only lasting legacy is that under his tenure, the majority of the bank’s lending tipped over from the private sector to the government. Following his departure in December 2011, he was promptly kicked upstairs to become the CEO of Habib Bank AG Zurich’s operations in Britain, in what we understand is mostly an emeritus position.

That is when the family brought in Sirajuddin Aziz, another seasoned banker with about 35 years of banking experience. This was a better decision than the previous two picks, but that is not saying much.

Going north: Sirajuddin Aziz accelerates branch expansion

Sirajuddin Aziz took over as CEO of Habib Metropolitan Bank in December 2011 and of the three people who had held that position until that point, he is the only one who came in with a plan of action.

Aziz began his career in 1977 as a fresh graduate of the University of Karachi. He applied for jobs at several banks, including Habib Bank. In fact, one of his interviewers was Kassim Parekh, the man who would become his boss several decades later. But on that day in July 1977, at least, Aziz was not going to become an employee of a bank named Habib.

Instead, he took an offer from BCCI, made to him personally by the bank’s founder, Agha Hasan Abedi. Aziz appears to be absolutely awestruck by Abedi, even to this day, even after all the revelations of the crooked and criminal dealings by that bank.

Aziz stayed with BCCI till the very end, serving as its country manager in China just before the bank’s collapse. He then joined the new management of a new bank being launched in the recently deregulated Pakistani banking market: Union Bank where he stayed until 2001, when he moved to Bank Alfalah. He was appointed CEO of Bank Alfalah in 2005, a position he retained until late 2011, when he was given the top slot at Habib Metro.

At Bank Alfalah, he led that bank’s meteoric rise from a small bank to becoming the sixth largest bank in the country.

Aziz’s strategy began with a simple premise: Habib Metropolitan Bank was widely regarded as one of the best lenders to Karachi’s exporters for their trade finance needs. It understood their credit profile better than most other banks. Why not, then, lend to their supply chain as well? It is not a bad thought process and would have worked well as a growth strategy for Habib Metropolitan, especially since the bank had very little presence outside of Karachi and Lahore.

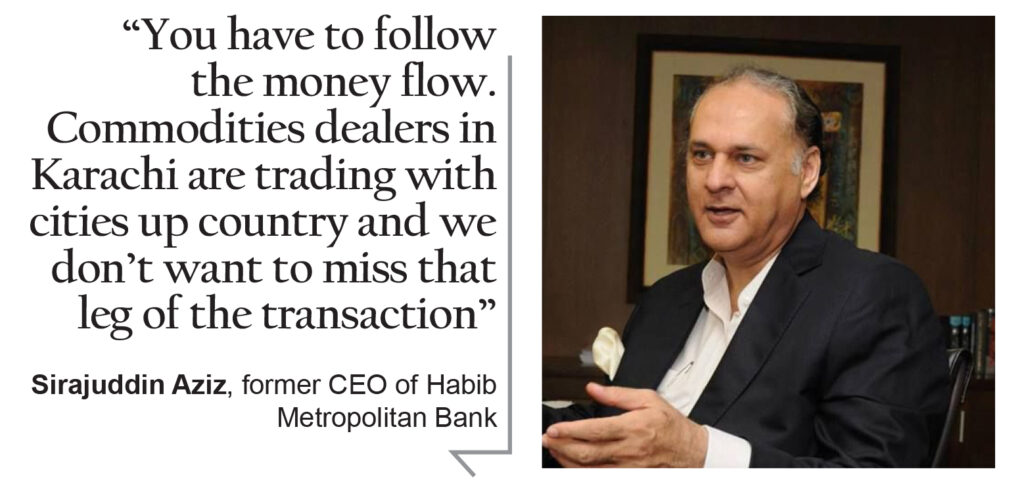

In an interview with Bloomberg soon after he was appointed to the job, Aziz said: “You have to follow the money flow. Commodities dealers in Karachi are trading with cities up country and we don’t want to miss that leg of the transaction.”

To that end, Aziz embarked on a strategy of carefully selecting where to open up Habib Metropolitan branches, focusing on small industrial and agricultural clusters, especially in the rapidly urbanising parts of Punjab. (When I first met him in mid-2012, the way he described each city he wanted to open a branch in and why – including many small towns I had never heard of – suggested that the man knew the Pakistani economy better than most people I have ever met.)

In retrospect, perhaps this should not have been surprising. After all, he had been wildly successful in growing Bank Alfalah to becoming one of the largest banks in the country in just six years. Over the course of his tenure as CEO, virtually all of the growth in the branch network has come in those small but rapidly growing towns.

Great on the deposit side, not so much on lending

Aziz said that the Habib family hired him specifically to do this job: grow them from being a middle market player focused on Karachi to becoming one of the leading nationwide commercial banks.

He appears to have delivered rather well on that: under Aziz, the bank added 126 new branches, taking the total network up to 289, a 77% expansion in the physical footprint of the bank.

The geographic spread is even more impressive: nearly three quarters of those new branches have been outside of Karachi and the bulk of those outside the major cities. From covering a total of 21 cities when he started off, the bank had branches in over 100 cities across all of Pakistan by the time he left the CEO position in June 2018.

In order to ensure that the bank’s brand name translates well into other parts of the country less familiar with English, Aziz had the name shortened on all branding to Habib Metro Bank.

What makes Aziz’s achievement even more impressive is that he more or less met the goal he explicitly set out to achieve. In 2012, he said he wanted to have 250 branches in at least 50 cities by the end of 2014. As of December 31, 2014, the bank had 249 branches in 50 cities.

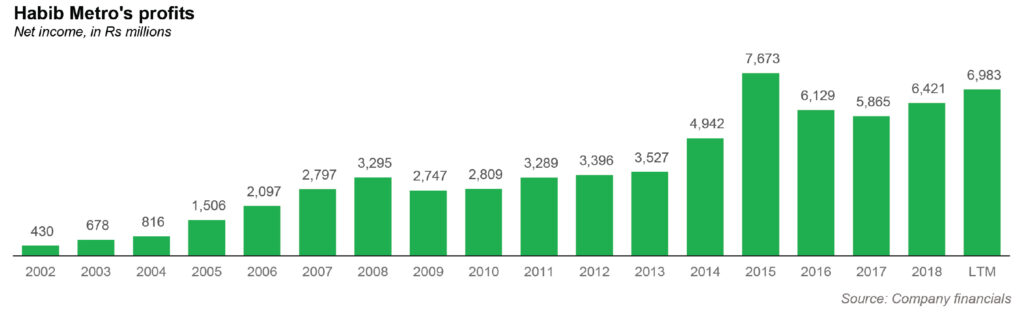

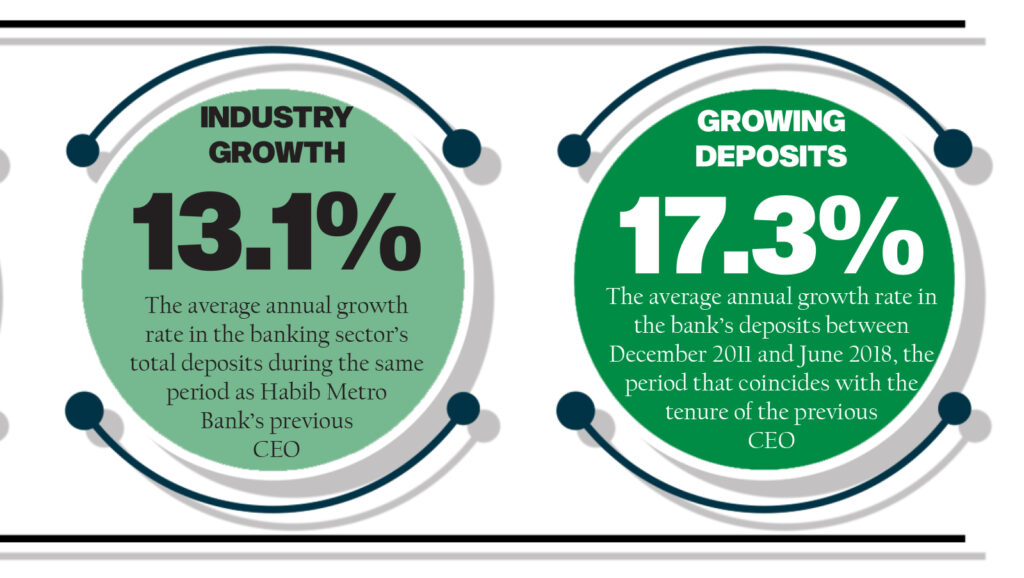

And that translated well into the bank’s financial results. Deposits grew at 17.3% per year under Aziz’s tenure as CEO, compared to just 13.1% for the industry as a whole. Net income has risen by an average of 11.4% per year between December 2011 and June 2018, compared to a 5.2% per year average for the industry as a whole during that same period.

There were, however, some drawbacks to the strategy, which – while sound in theory – did not look very sophisticated in practice. Yes, the bank knew exactly where to place its new branches in order to draw deposits, but ultimately a bank needs to know how to lend. And on that front, Habib Metro left much to be desired.

While the overall asset book of the bank grew at 13.5% per year under Aziz’s leadership, the private sector loan book has grew by an average of 9.1% per year. The bulk of the growth has come from the bank plowing its money into government bonds. And even on the private sector lending side, a substantial proportion of Habib Metro’s lending portfolio is concentrated in low-margin trade finance.

The bank’s management explicitly ruled out consumer lending and seemed to think that trade finance is a nice specialty to remain focused on. But when asked why so much of Habib Metro’s asset book was in government bonds, for a man who is ordinarily quite eloquent, Aziz was unable to give a straight answer.

That sort of evasion – and the disinterest in lending evident from the bank’s financial statements – suggests that this bank is a one-trick pony: it knows how to attract deposits, but not how to lend them out.

And at least part of the reason why the bank’s loan book did not increase substantially was because lending decisions were heavily concentrated at headquarters in Karachi.

When the bank had the majority of its branch network centered in the city, that was probably less of an issue. But as the bank grew bigger and further afield, it needed to entrust more responsibility to its branch managers and regional managers, something that the senior management had identified as a problem, but was initially slow in implementing solutions.

Then there is the fact that the bank sees its core business as trade finance. Trade finance is the oldest form of banking there is, but the way it is practiced in Pakistan, it is lazy, low-margin business. Here is how it works. If you are a new customer, you walk into the bank and they ask you to post collateral for the loan, which would be fair were it not for the absurd policy that requires the client to post 110% of the value of the loan they want in cash/treasury bonds. In effect, the bank asks you to show that you have the cash that you want to borrow from them, rather than determining ability and/or willingness to pay the loan back.

For clients who have been with the bank longer, the collateral requirements are a little less stringent, but then the margins on trade finance tend to be far lower that commercial lending for other purposes. The whole point of the northern expansion was to diversify beyond trade finance into related areas of lending and get better risk-adjusted margins.

Islamic banking: off to a slow start

Habib Metro has had an Islamic banking division since the fourth quarter of 2004, but it was a backwater that the bank’s management never paid much attention to. In August 2014, however, the bank formally gave its Islamic banking division a brand identity – Sirat (the path) – in keeping with the tradition of naming the Shariah-compliant divisions using Arabic words that vaguely sound like religious terms.

However, while other banks, both for reasons of customer preferences and regulatory relaxations, the net interest margin of the Islamic banking division tends to be higher than that of the rest of the bank.

At Habib Metro, however, that is not at all the case, with the Islamic banking division’s net interest margin nearly 63 basis points lower than that of its conventional banking business. Maybe if they paid more attention to this line of business, its margins would improve, but it appears that the bank is still not entirely ready to put its weight behind it.

For one thing, when launching a new brand, one would expect an advertising blitz to ensure that the brand catches one. For Sirat, Habib Metro pretty much did not even bother. This suggests that while other middle market players continue to invest in their Islamic banking divisions to grow their deposit base, Habib Metro risks being left behind.

Mohsin Nathani: the (relatively) new man on the job

Sirajuddin Aziz’s successor was announced in February 2018, a few months before Aziz left the job. Mohsin Nathani – then known in the Pakistani banking industry as a global banker with a career previously focused exclusively in the large multinational banks that have done business in the country – was a somewhat unexpected choice: when he had left Standard Chartered in September 2015, it was assumed that he had retired. Hence, most outside observers did not even realise he was available for the job.

Nathani’s career is the kind of success story middle class Karachiites dream of for their children. Schooled at St Paul’s and St Patrick’s, Nathani went on to attend the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) in Karachi for his undergraduate and masters degrees in business, graduating from IBA in 1987.

In 1990s, Nathani started working at Citibank Pakistan back when it meant something to be at Citibank Pakistan. These were the heady days when Citi was reinventing what it meant to be a banker in Pakistan, introducing entirely new classes of lending to the country. So trailblazing was Citi’s team back then – and such a tremendous vehicle for career growth – that Nathani left in three and a half years to become head of corporate banking at ABN Amro Pakistan, a mere six years after having started his career.

From ABN Amro, Nathani moved back to Citibank, but this time in roles across the Asia-Pacific region as well as the Middle East. From Citi, he moved on to Barclays in the UAE, which ultimately became his vehicle back home, when he returned to Pakistan as the country head for Barclays’ newly launched branches in Pakistan.

That tenure was unquestionably a disaster, though not because of anything Nathani did: it was just bad luck and bad timing. Barclays Pakistan never really stood a chance, and within three years, Nathani saw the writing one the wall and jumped ship to become CEO of Standard Chartered Pakistan when Badar Kazmi left the job to head over to SCB’s operations in Saudi Arabia.

Nathani served as CEO on SCB Pakistan for a little over three years, and then of SCB in the UAE for another year and a half before retiring – the first time in 2015.

Yet sources close to Nathani tell Profit that retirement did not suit him. He was still in his prime, at just over 51 when he left SCB. He still had at least one more solid, long innings left to play. And while his successful international banking career meant that he did not need to work again, he clearly wanted to.

The problem with being a retired bank CEO in Pakistan who wants to get back into the game is that there are not a whole lot of options. Bank CEO positions do not open up every day, let alone positions that match the career profile and character of the person seeking the position. For a person who started off his career as one of the young buccaneers who transformed Pakistani lending to then come at the later stage of his life to the oldest of old banking houses in the country, where his job is to preserve and not build, must be a surreal experience.

We say “must be” because in our interview with him, Nathani did not indicate anything other than enthusiasm for the job. And while it is still early days in his tenure, he certainly seems off to a solid start, with both deposits and profits continuing to outpace the broader sector as a whole. Also the branch network has grown to 390 branches in 130 cities.

Yet when asked to lay out the bank’s strategy going forward, Nathani said nothing new: it is the same strategy set by the owners of the bank who want nothing new and nothing different. It seems that this branch of the Habib family loves to hire capable CEOs, but sees them as mere managers, not strategists.

One could argue that such an approach is unhealthy or unsustainable in the long run, but we suspect they would respond by pointing to their financial results, which are certainly hard to refute as proof of the bank’s success.

Corrections and amplification: An earlier story in a previous issue of Profit incorrectly stated that Habib Metropolitan Bank’s compliance function was struggling to keep pace with the bank’s growth. The error is regretted.

A brief history and knowledge about HabibMetro. HabibMetro employee retention rate is higher than any other bank on Pakistan.

It’s a nice place for cushy jobs that don’t require much effort.

Well researched article. Lending is always an issue in Pakistan due to stiff competition among banks due to which the spreads are so low that it is not just prudent to lend when you can earn similar spread in risk free instruments. Reason why the spreads are so low that they are virtually equal to that in risk free investments is another interesting topic in itself.

Spreads are actually very high in Pakistan compared to other countries in the region.

That’s true but by spreads I meant the spread over risk free instruments. It’s virtually non existent in case of Corporate lending and just 1-2% on lending to SMEs. Faced with risk of default, banks are happy to invest in T-bills and PIBs and earning 4-5% spreads without taking any risk.

so lack of documentation means there’s a limited pool of potential borrowers and every bank chases those guys and that’s why there’s little money to be made lending to them. government’s appetite also keeps growing because it’s finances are perennially mismanaged. so better to just lend to the govt. no need to hire credit officers or do the legwork necessary to evaluate credit worthiness.

All banks are in the business of borrowing interest free from current account holders and lending risk free to the government. They mint money doing this. They don’t even have to keep up with technological advances. In other countries banks are shutting down branches and doing most of their business online. In Pakistan it’s the opposite! They even managed to get the SBP to put up barriers to online payment startups to prevent any competitors getting a foothold. It’s a very nice racket they have going on.

Really loved the reporting standards you guys are setting. Can easily surpass BR

Comments are closed.