There is an excise levy known as the ‘Sin tax’, and a few months ago, it was the talk of the town. Notwithstanding Pakistan’s obsession with giving everything a religious twist, a sin tax is essentially just the concept that if you are causing harm to society as a result of your choice to consume certain products, you need to pay the cost for that harm as well.

The question often raised with a ‘sin tax’ is what determines a sin, and whether it is the government’s job to be deciding what does and does not constitute a sin. Without moral proselytizing, the answer lies somewhere in basic, second chapter, A levels economics: positive and negative goods. Here, the important bit is negative goods or negative externalities, those goods which cause harm to society around you. The classic example, and rightfully so, are cigarettes.

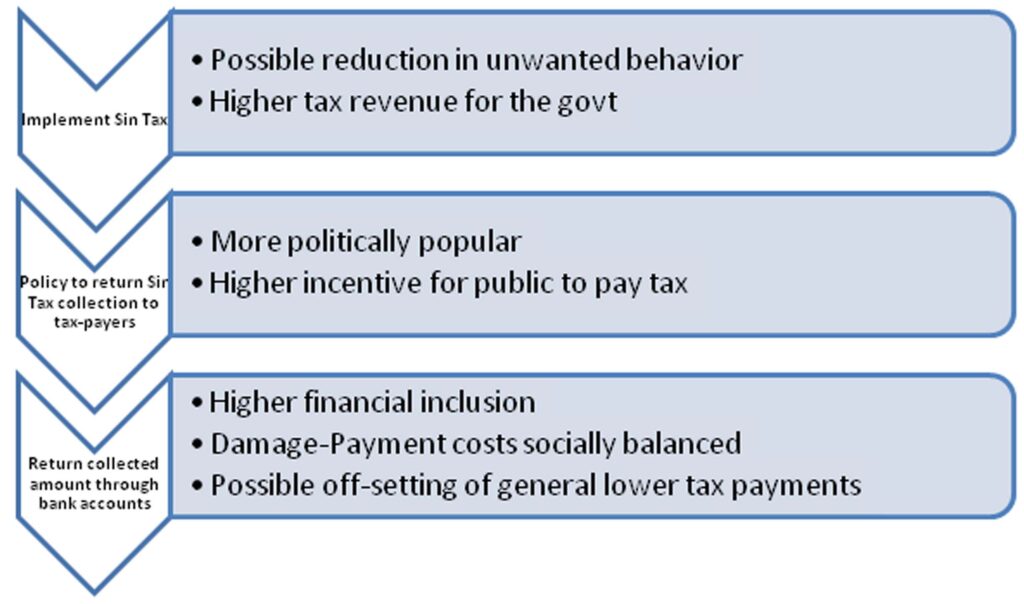

While most governments around the world use the tax collected under this policy on health and environmental cleansing projects, one country decided to return all tax money back to its citizens. The process they chose was to do so through tax refund. It turned out to be a massive success. Could the implementation of a similar policy be possible in Pakistan?

Profit discusses sin tax; it’s merits, demerits, and effectiveness; and how it holds an incredible opportunity to resolve the unbanked population problem.

A short history

Let’s go back to A levels economics just for a moment. Think about all those graphs, supply and demand crissing and crossing and areas underneath the lines to calculate. Think about the types of demand, and go back to one particular king: inelastic demand. These are products that are either addictive or necessities, so no matter how high their prices go, it will not affect demand. Yes, competition may affect certain demands, but overall the product continues to sell. The classic example, once again, are cigarettes.

“I have sold a Rs 100 pack for Rs 350, when the price hiked or when the supply went down, and still my sales were not affected,” said Qasim Ali, the owner of a paan shop, a usual cigarette selling spot in Pakistan. He sits in a semi urban area of Saddar, Karachi, and has frequent customers ranging from the ages of fifteen upwards and belonging to different social classes.

The Ministry of National Health Services and Regulations had announced on December 4, 2018 that a ‘sin tax’ would soon be imposed on cigarettes and sugary beverages. A summary was forwarded to the Cabinet Division in this regard. The ministry recommended imposing a tax of Rs10 per cigarette packet and Rs2 per 100ml of soft drinks. The intention by Pakistan’s health ministry was to reduce smoking rate and increase tax revenue with one policy. Fast forward to February 20, 2020, and the federal cabinet rejected this proposal, citing legal and administrative problems in its enforcement.

But the reasons cited for rejecting the policy had nothing to do with the policy, rather it was a matter of who would get to implement it. The ministry had proposed the Sin Tax to “finance the health insurance scheme and fatal diseases programme” of Prime Minister Imran Khan. But the then-finance minister, Asad Umar, raised concerns that since under the Rules of Business, it is Revenue Division’s prerogative to propose tax measures, it was not appropriate for any other ministry to make taxation proposals.

Imposing a levy through a finance bill may not have withstood judicial scrutiny, and then there was the added issue that revenue generated through a levy instead of a tax could not become part of the federal divisible pool that is shared by the provinces and the centre.

However, even if this policy had somehow gotten to the implementation stage, the government might still not have achieved either objective. And while the thought is a double whammy of failure, there are lessons from around the world that we can use to craft a better, more successful way to generate this sort of revenue while discouraging social ills.

When the news of this proposal first aired, hysteria broke out on social media with many primarily concerned with the title of the tax. Those ascribing to the viewpoint of the ‘sin tax’ being a hilarious or inappropriate title included government officials as well as the tobacco industry.

PTI Minister Faisal Vawda, no stranger to sickening displays of adolescent machismo, was naturally the first to share his views on the issue, taking to twitter, where he said “I’m a chain cigarette smoker myself and I appreciate all the measures taken by the government to discourage smoking and I understand it’s injurious to health but this term ‘Gunnah Tax’ is inappropriate,” he complained. “If this is gunnah then what would we name and term the actual gunnahs.”

And while his hurt sentiments could be set aside for the greater good, the stakeholders that did matter in this situation were the tobacco farmers. Many of them, particularly from several regions in the KP province, put forth the argument that the government using this terminology was an attempt ‘to create a negative image of their work.’ They decried the government for “calling their earnings gunnah”.

Another short history

‘Sin Tax’, as it came to be known, was first introduced in 1643 Britain as an excise tax on distilled spirits. So for starters, if people like Mr Vawda find the term offensive or judgemental, that is exactly how it was meant in Restoration era England. But some words are mere relics

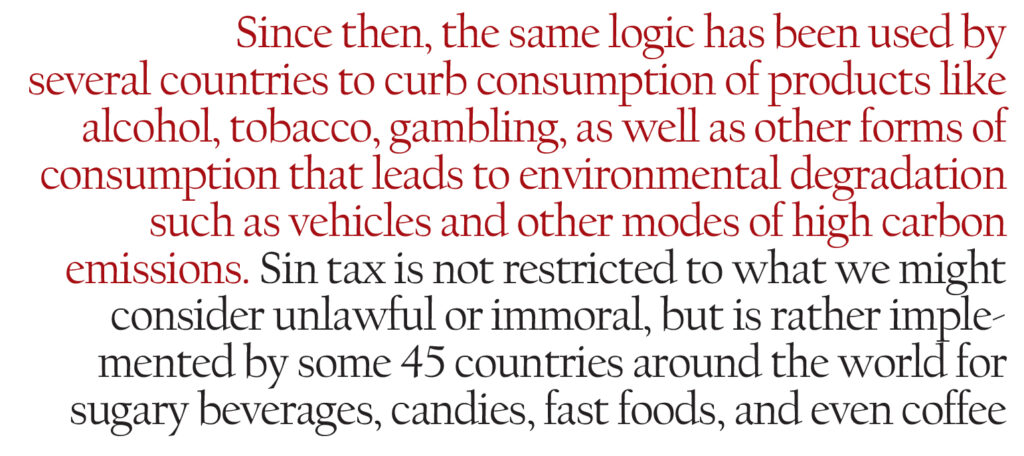

It was not until 1776 then that Adam Smith gave his approval to the policy, saying that taxes on cigarettes, rum and sugar are appropriate since they are not essential for life but are widely consumed. The US started taxing tobacco products during the Civil War and by the 1920s these taxes had become widespread as advertising also doubled the number of smokers. Needless to say, sin taxes have worked better for them than prohibition.

Since then, the same logic has been used by several countries to curb consumption of products like alcohol, tobacco, gambling, as well as other forms of consumption that leads to environmental degradation such as vehicles and other modes of high carbon emissions. Sin tax is not restricted to what we might consider unlawful or immoral, but is rather implemented by some 45 countries around the world for sugary beverages, candies, fast foods, and even coffee.

In December 2018, the National Health Service (NHS) Director General, Dr Assad Hafeez, told Dawn that Thailand, as well as a number of other countries, have similar taxes that are earmarked for healthcare services. He cited India’s example that imposes a sin tax on gutka and paan masala, and the tax collected from there are then spent on the healthcare sector. Pakistan’s aims were not any different.

This sin tax was to be collected and then spent on our own healthcare expenditure by the government, at least that is what was claimed. The general public rarely trusts the government (rightfully so), and in Pakistan, even less so. So you still cannot expect wide ranging support for a sin tax simply based on the argument that the government will spend it on healthcare. But it is still a place to start.

How does it work?

Let us take the examples of a smoker and a car owner. When one person smokes, it is not just their own money and health at stake, but people around them also inhale smoke passively and the breathing space around them also becomes toxic. Likewise, when someone drives a car, it is not just their money on car and petrol, but the carbon emissions from their vehicle contribute to environmental degradation, and possibly road congestion as well as noise pollution.

A sin tax, therefore, becomes a policy to make the individual causing these effects on non-users pay for these extra negative impacts as well. So when someone pays extra on cigarettes or fuel, and that money is spent on public healthcare and green policies, even those people benefit who have not directly paid this tax, and thereby the harm and payment are balanced – at least in theory and economic means.

Such taxes are collected from retailers and sellers, which in turn increase the retail price for the end consumer. So if anyone does not want to pay extra for smoking or driving, their only option then becomes to not smoke or drive at all, which is the other side of this tax – discouraging consumption of goods with negative externalities. This form of excise taxes makes up for considerable tax revenue for governments all over the world. According to “The Balance”, the American state Rhode Island depends on sin tax for approximately 16 percent of its revenue. It also shows that in 2014, revenue from sin tax was $32.5 billion which soared to $98.3 billion in 2015.

In a democratically managed economy where healthcare is taken seriously and tax collection is regulated and strongly implemented, sin tax can have three main arguments in its favor: it reduces consumption of unhealthy products, pays for society’s costs, and is popular with voters. Out of these three, there is evidence available for the last two consequences to be true and effective, but as for the first one, the jury is still out on that one.

The rules and effects are pretty much the same in Pakistan too. Dr Ismat Tahira, a medical doctor and health expert at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre said that such taxes may be useful to discourage only new smokers. “The measures taken by the government such as higher costs, or printing images of disturbing medical conditions caused by smoking on cigarette packs can be useful in stopping new smokers from entering the customer base of tobacco companies but I don’t think it has any impact on those who are already addicted.”

Qasim Ali, the shopkeeper from the beginning of the article, said that he has cigarette products ranging from Rs 50 to Rs 280, and he has also sold the lowest costing cigarettes for twice their usual price at times such as in rainy weather or during a shutter down strike, and he still did not experience any change in the smoking behavior of his customers. “Cigarettes are not a luxury product, not for smokers at least. It is like food or other staple products. They will pay whatever the price. Very few, if any, even change the brand they smoke due to cost changes.”

Qasim makes 3.5 percent profit on local cigarette brands and at least 5 percent on international brands, with no upper limit, often reaching up to 12 percent. He said, “My customers who smoke international brands, expensive ones, are usually affluent to begin with. An increase of 10, 20 rupees doesn’t mean anything for them. Those who smoke the lower brands also rarely show any change in their behavior.”

Going by this, we can estimate the economy wide impact of this sin tax as well. And the true impact of such taxes is in fact the actual reason the PTI government came forth with this suggestion, not the protection of health or reducing rates of smoking. According to the summary sent to the cabinet by the health ministry, around 4 billion cigarette packets are sold every year in Pakistan. It has been estimated that the annual income from the additional tax to be around Rs70 billion.

As far as popularity with voters is concerned, there is an obvious moral justification attached to the argument of sin taxes, and discounting Pakistanis’ obsession with adding religious interpretation to every word and phrase, it is usually a popular policy, even from those who are going to pay for it.

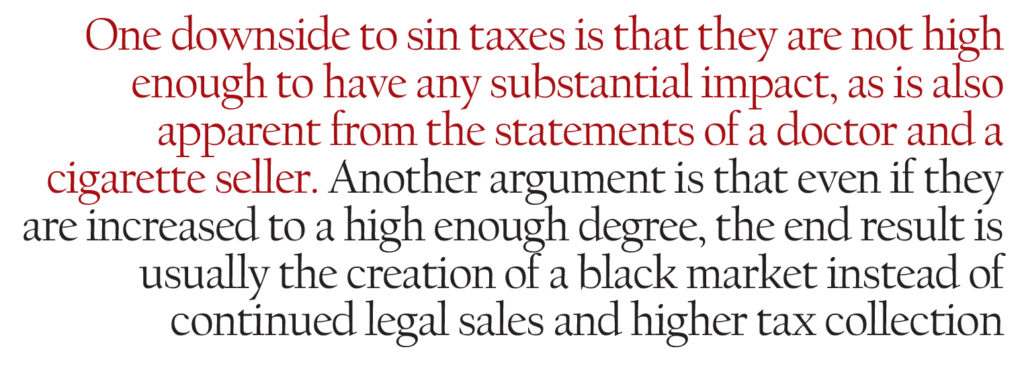

The flipside

Now let’s move to the downsides of sin tax. Taking help from The Balance again, one downside to sin taxes is that they are not high enough to have any substantial impact, as is also apparent from the statements of a doctor and a cigarette seller. Another argument is that even if they are increased to a high enough degree, the end result is usually the creation of a black market instead of continued legal sales and higher tax collection.

Another negative aspect of sin tax comes from the inherent inequality in the policy. Benjamin Lockwood, a professor of economics at Wharton conducted a study along with Dmitry Taubinsky from Dartmouth College examining the impact of sin taxes in 2017. In a conversation with Wharton’s podcast Knowledge@Wharton showed he shared that there have been studies that show that poorer consumers tend to consume things like cigarettes and soda at a higher frequency than richer consumers.

Sometimes this stems out from higher costs of alternative options, while sometimes it is simply because of lack of availability of healthier products in rural areas. “Survey evidence suggests that at the bottom of the income distribution, people drink about twice as much sugary soda than at the top of the income distribution”, Lockwood said. This is how all indirect taxes behave, by creating a regressive effect on lower income groups. To understand it in layman’s terms, if two people earning Rs 1,000 and Rs 10,000 a week have to pay the same amount of Rs 100 per week in taxes, the impact of the tax would be 10% for the lower income person while it will be 1% for the higher income group.

There is one more interesting factor to consider, above and beyond the positives and negatives of sin taxes, which may be understood as “elasticity”. Irrespective of the inherent effectiveness of a sin tax policy, the final impact depends on the products that these taxes are being implemented on. This might be the make or break factor where Pakistan’s policy fell short while a particular Canadian policy shot through the roof. One such scenario arises when sin tax seems to do little to cut down smoking but has a massive impact when implemented on carbon footprints.

Why hasn’t it worked yet?

While it is important to note that this term is neither coined by PTI nor bears any link to religious definition of sin, it is equally important that this sin tax would have done little if anything to lower the rate of smoking or smoking related diseases in the country. There is no denying that such taxes, especially when applied on cigarettes, add massively to the national kitty and are also politically popular, as opposed to, say, property taxes.

But the changes in prices of tobacco products do not bring about any change in the smoking behavior of the people. More on this later, for now let’s take an example of something similar from another part of the world, which in fact did turn out to be a success and not just politically but also economically.

Despite all the benefits of the policy in general, there is a flipside to even this potential benefit of sin tax for Pakistan’s economy. Such tax is going to add twice the tax burden on the international brands of cigarettes being sold in the country. According to an article published in Profit magazine on December 8, the two multinational (tobacco) companies, with a market share of 67 percent, contributed Rs89 billion (98 percent) in excise duties and taxes during the fiscal year 2017-18. On the contrary, the locally-registered companies were paying only 2 percent in taxes despite having 33 percent of the market share.

The impact for these international companies will be double because imported cigarettes are already subjected to ‘sin tax’ in the form of excise duties, and any further taxation would be a case of duplication that would result in a repetitive increase in the tax on cigarettes. This, if leads to any fall in the sales, will cause the production volume to decrease, reducing the government’s revenue. In fact the illicit trade of cigarettes in the country could rise.

Therefore it can be seen how this sin tax is self-defeating in both its targeted results, achieving either reduction in smoking or increase in revenue, but not both. If this sin tax leads to an increase in the revenue, then it will mean that the smoking rate has not gone down. And if the smoking rate decreases then there is bad news for the net tax collected from this industry.

A case study

Let’s zoom out for a moment. We have talked about how the sin tax was received with Pakistan and what the sin tax is. But where in the world exactly has it worked before, after all, there is something about it that we find important enough to discuss and bring to the table. More importantly, how has the concept been moulded and sculpted to make it work, and how and could it ever work in Pakistan? One example that we would urge you all to explore can be heard on Episode 949 of Planet Money on NPR.

The brilliant episode follows economist Arthur Cecil Pigou who, almost a century ago, came up with the idea for fixing enormous problems like carbon emissions and products like cigarettes with negative externalities. Pigou was the only economics professor at Cambridge for 35 years and was living near London in the early 1900s. This was also the time when air pollution was starting to become a huge problem. Coal was being burnt heavily and smog had covered the city, known as London fog back then. It was thick. It covered everything. It was an oily substance that covered furniture, enter your rooms. You would breathe it. It killed people. It killed animals.

Pigou took it on as an economist. He also saw the cost of the infamous London fog. He thought it would increase health care costs. It would affect vegetation, livestock. It would wreck your furniture. Everyone would have to buy new furniture. Everyone had to wash their clothes more often. Those are all costs. And the people burning the coal weren’t going to be paying for this; innocent bystanders would. Pigou’s contribution was not the realization that private companies add to problems for society, rather he came up with a solution that he explained in his book “Wealth and Welfare”. That is where he defined negative externalities and graphically explained personal marginal costs and social marginal costs, and putting them together came up with sin taxes. Fast forward to 2016, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Canada was to have a carbon tax. From January 1, 2019 there is a $20 tax per ton of carbon, with an added feature of adding $10 for each of the next three years, making it go up till $50 by 2022. (50 Canadian equals approximately USD 38).

Discounting the political decision of how pollution was valued at this much and not lower or higher, the fact of the matter is that where does this carbon emission come from? That would be gasoline, coal, and natural gas. So the tax would be implemented on all these products, which in any modern economy would lead to an increase in prices of almost everything. This, however, will be more progressive than let’s say tax on a cigarette pack or a coke bottle.

That is because while even baking a loaf of bread uses some type of fuel, the consumption and therefore carbon release by an aircraft or a luxury car far exceed the ultimate carbon emission of regular everyday products. So, if you are buying baked goods, you would be paying at most in pennies, but if you are taking a flight, your tax amount would be much higher. This will also translate to potentially switching a personal car for a bus ride, or investing in a fuel efficient car instead of a shiny racing vehicle. However, when it came to Canada, Trudeau introduced one more element to this policy overcoming the tax resistance by the general population in one single sweep.

The Trudeau government said that they will give all the money back. Not invest in healthcare or any public policy, but return back cold hard cash – in equal amounts to all those who have paid this sin tax. This means that let’s say $1,000 was collected from 5 people with one of them paying only $10 while another pays $400. When this money is returned, they both will receive $200, along with the other three people irrespective of their individual contributions. It came out as a policy of “free money” for most people rather than a tax amount that they needed to pay.

Now, since writing everyone a check was also not the most practical idea, the Canadian government came up with another additional feature – simply check a box on your income tax filings if you wanted your pollution refund. In Canada, where it is much more likely than Pakistan that people do indeed pay their taxes, when they started checking this box they found the balance on their income tax to start to drop.

People had started to get their carbon tax rebate back. Looking at the entire policy we see so many motivations that actually work – incentive to support the policy, incentive to file taxes, incentive to spend less because irrespective of the rebate the prices are now higher, and finally choosing to spend less and less so you can get more and more in return from those who continue to spend more without regards to this tax. Research conducted afterwards revealed that 8 out of 10 Canadian households received more in carbon tax rebate than they spent on goods with this tax. The reason is simple – wealthier people pollute more, which is why they should pay more.

The math

To understand how this policy would work in Pakistan, let’s use some numbers. Let’s assume there are 150 people in a locality. 100 of them own petrol-run cars. Out of these 100, 30 people consume 25 liters per day on average while 70 people consume an average of 10 liters of petrol per day. The remaining 50 people do not use petrol at all.

Let’s also assume that only 120 of the total 150 people have bank accounts, or any sort of digital or traditional record of their finances, tax payments, and so on. Now the government imposes, Rs 20 per liter of additional sin-tax petrol. The costs and tax calculations will become as follows:

Total petrol consumption (30*25 + 70*10 + 50*0 = 1250+500) = 1,450 liters per day

Total sin tax (1,450*20) = Rs 29,000

Now the individual additional costs would something like this, everyone using 25 liters per day would be paying additional Rs 500 per day (25ltr*Rs20) while people consuming 10 kms per day would be paying Rs 200 per day. This means that 30 people would contribute Rs 15,000 while 70 people would contribute a total of Rs 14,000 into the tax. And the remaining 50 would not be paying anything.

However, when this collected amount is returned back to the same 150 people, everyone gets around Rs 193 (29,000/150 = 193.3333). This means that those adding more to the carbon emission would in fact be paying a net of Rs 307 (500 -193) while those who are creating lower pollution comparatively would be paying lower net tax of Rs 7, while those who are not contributing anything towards environmental damage will receive net Rs 193. This way, those who are responsible for a large chunk of the damage will be directly compensating those who are being damaged, and social costs will be balanced as well.

This leaves us with the very final step of financial inclusion. If the 30 people who do not own bank accounts wish to receive their individual Rs 193 per day, they will have to get included in the financial records. And if they do not, the government gets to keep Rs 3,860 in sin taxes. Their share of sin taxes, which could have been refunded now stays with the government, off-setting to some extent, however minimal, the effect of non-payment of taxes otherwise.

For now, we are planting trees, sometimes those that soak up the entire underground water of a city, as we saw in Karachi’s case. We are offering money backs on mobile wallets to make more people open digital accounts. We are also – almost constantly – extending deadlines for filing tax returns. Right, left and center, the current government is trying to react to and resolve issues like global warming and tax evasion with little to no success. We also struck down a sin tax policy which might have actually done us a favor, but that might be good news, because rebranding and redesigning that very policy might now be the ultimate success story for the PTI government.

Admittedly, it is usually not enough and it is not equitable despite the seemingly simple math. The problems with Pakistan is always going to be a deep rooted distrust of government policies, and especially with trusting them with tax money to actually spend the collected amounts on healthcare projects that end up helping the larger population. Resistance to taxes is always a condition to consider. But replicating Canadian model would resolve all these issues in one go.