To have a burgeoning solar energy industry, it can be easy to think of more complicated things that a country needs to have: a strong supply of photovoltaic panels, a robust regulatory environment, and a transmission infrastructure that can handle the distributed generation of electricity efficiently. It is easy to forget to think about the most basic ingredient of all: sunlight, and how much of it a country gets on its territory.

On that matter, Pakistan is unquestionably blessed. Solar experts believe that an area needs a minimum of four hours of peak sunlight in order for solar energy to be economically viable. Peak sunlight is not just any time between sunrise and sunset: it is when daylight is bright, and directly shining on solar panels. The goods news for Pakistan? Most of the country has 300 or more sunny days every year.

And the overwhelming majority of the landmass of the country gets seven or more hours of peak sunlight every year, according to a 2012 research paper by Saifullah Khan, Mahmood-ul-Hasan, and Muhammad Aslam Khan of the University of Peshawar. Their research examined data from 1931 through 1990 for most of the country.

Solar energy, therefore, makes all the sense in the world for Pakistan as a major source of electricity, even taking into consideration the limitations of energy storage technology. And given the precipitous collapse in the prices of photovoltaic cells, which has dropped by more than 60% over the past decade, one would assume that solar energy would be more of an energy source for Pakistan.

The numbers, however, tell a different story. For the 12 months ending January 2020, solar energy accounted for just 0.58% of Pakistan’s electricity generation, or 722 gigawatt-hours, according to data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). That is up from zero as recently as 2014, to be sure, but still a long way to go before it becomes a major source of energy for the country.

That NEPRA data, of course, does not count solar electricity that is being generated by private homes and businesses, and not connected to the national transmission grid. There is at least some evidence to suggest that there may a substantial portion of solar energy generation capacity in Pakistan that is installed and being utilised, but not counted because it is not connected to the grid.

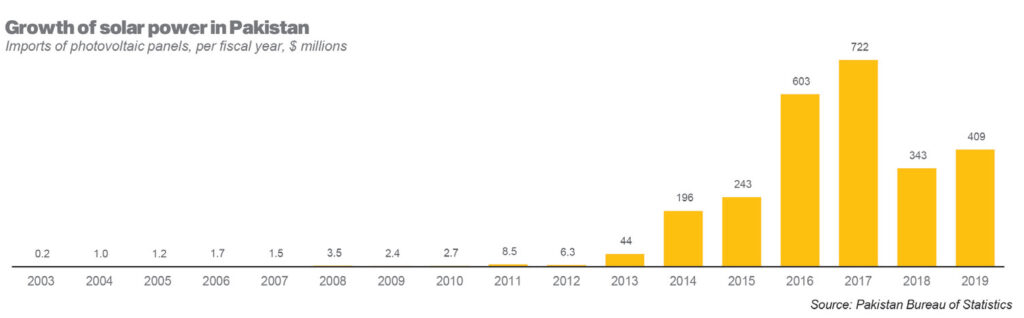

Imports of solar panels have risen from as little as $1 million in 2004 to a peak of $772 million in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2017. While they have since dropped down to $409 million in fiscal 2019, the country’s imports of solar panels appear to be a strong upward trajectory, growing at an average rate of 15.9% per year in US dollar terms (22.6% per year in Pakistani rupee terms) in the five years between 2014 and 2019.

While a substantial portion of those imports are for grid-scale projects, a significant proportion are for domestic, commercial, and industrial users who are not necessarily connected to the grid.

Given the country’s chronic energy shortages – and the public’s increasing scepticism of the state-owned utility companies to deliver a consistent supply of electricity – it makes sense that more and more Pakistanis are adopting the use of solar technology to meet their energy needs. Could solar be the future for Pakistan? Maybe, but only if the government gets out of the way.

Demand, supply and costs

For advocates of solar energy, the idea is for everything to go completely solar. Yes, there are already some houses and companies that have on an individual level gone solar.

However, expecting the government to initiate sweeping change and switch to solar is asking too much. If there is to be a switch to renewable energy, particularly to solar, it will have to be a gradual, natural switch. One that begins more as a trend than as a necessity, because implementation and execution is where all great, common sense ideas go to die. So can solar become the future of energy in Pakistan? After all, how much electricity are we using exactly?

According to the report of the International Energy Agency (IEA), the average energy demand in Pakistan is approximately 19,000 megawatts (MW) against the average generation of around 15,000 MW. This demand goes beyond 20,000 MW from May to July, when the summer is at its peak and air conditioning systems place an extra burden on the national power grid, often causing power cuts.

The IEA also forecasts in its report that the electricity demand would rise to more than 49,000 MW by 2025 as the country’s population increases and the economy grows in size. This is a crucial situation and at this time the government really needs to think of an alternate solution. Solar energy is the obvious candidate.

And once again, the government cannot be expected to go knocking on doors with solar panels installing them to houses one by one. What the government can do, however, and actually should be expected to do, is make it easier for businesses to provide solar electricity. They can also encourage consumers to switch to solar panels, rather than creating hurdles in their way as they are currently.

Almost 51 million people still do not have access to electricity in Pakistan. This gives a great challenge to the Pakistani government and policy makers, as electricity is a necessity of modern life. But why remain a stronghold for the old guard?

Nauman Khan from the Pakistan Solar Association was of the view that in Pakistan, solar was being taken as an industrial item in the consumer market. “In the prevailing conditions, solar is considered a luxury, but it will turn into a necessity soon,” he says. “People initially used solar to avoid load shedding, but this is a low cost billing system. One unit of solar costs Rs6 per unit, and if a battery is added, then it costs Rs9.5 per unit.”

“Meanwhile, we are getting electricity at the rate of Rs18 to Rs25 per unit. Different companies like LESCO [Lahore Electric Supply Company], KESC [Karachi Electric Supply Company, the old name for K-Electric], etc have different tariffs and rates. Simply speaking, solar is just cheaper, and this may just be a bigger attraction to the consumer than environmental benefits of sustainability.”

“But despite that, the future is solar,” he goes on to add. “This is not just a Pakistan issue or a capacity issue, this is global. The USA and Germany don’t have load shedding, why do you think they are shifting to solar? It’s better to get on the train now rather than hanging onto the railings when it’s already full.”

“Back when God installed the solar system, that was it. All that was needed from then was the panels, and even those are really low maintenance,” says Saeed Hussain, a veteran industry expert, who is also head of the Solar-Thermal division of the Ministry of Science and Technology.

Enter the government

So what prevents solar energy from taking off? Well, as pointed out earlier, where the government should be encouraging solar proliferation, they are instead causing hurdles. Under the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act, 1997, NEPRA is the sole regulator in the power sector.

NEPRA issues generation licenses, establishes and enforces standards, approves investment and power acquisition programs of the utility companies, and determines investment tariffs for bulk generation and transmission and retail distribution of electric power.

The Alternative Energy Development Board (AEDB) was established as an autonomous body with the aim of promoting and facilitating the exploitation of renewable energy projects in Pakistan. It has been designated as a ‘one-window’ facilitator at the federal level for processing solar projects of all sizes.

The Government of Pakistan’s first steps towards firm support of renewable energy in its energy mix came in 2006 when it made the Policy for Development of Renewable Energy Generation (the 2006 RE Policy). The AEDB has been planning to develop cost-effective alternative and renewable energy-based power generation projects through private investors under the Renewable Energy Policy 2006 on the IPP model (independent power producer).

The Government of Pakistan’s role in all of this has been offering incentives to investors for solar power development in the country. Investors have been presented with rewarding financial incentives that are of key interest for them to come to this market. Provincial governments, particularly the Government of Punjab, have taken the lead on facilitating development of solar power in Pakistan.

The goal that the federal government has set for the AEDB is to ensure 5% of total national power generation capacity to be generated through renewable energy technologies by the year 2030. That may seem like very little and very slow progress, but even that is coming along at a snail’s pace. In addition, under the remote village electrification program, AEDB has been directed to electrify 7,874 remote villages in Sindh and Balochistan provinces through ARE technologies (Alternative and Renewable Energies Technologies). However, there are certain hurdles unique to the industry that make this a difficult task and even 5% solar coverage a big undertaking.

“The future of Pakistan is in renewable energy and the solar industry is top most in this kind of energy. However, the problem in Pakistan is that the rental power station does not let the solar scene grow,” Saeed Hussain explains to us.

“The new PTI [Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf] government has also paid the rental power stations in order to reduce load shedding. If the government also pays to the rental [power companies] and to the solar then both will suffer and neither will be able to work properly. Almost the entire world is shifting to solar power while we in Pakistan are moving towards rental and coal power, which has no future.”

The rift

There are then issues beyond this, and there are questions of import quantities and market shares. For starters, Pakistan has a problem in that all parts needed to install solar panels are imported, which makes things difficult. Local industry stakeholders say that the government does not assist them in allowing them to build these materials themselves, while the government claims that the industry imports sub-par materials. And in this epic match of he-sad, she-said, the dream for 5% solar electricity coverage remains an elusive one.

“One container has a maximum of 150 to 200 kilowatts of solar energy and almost 5,700 containers of solar panels come to Pakistan each year having a capacity of approximately 150 kilowatts,” says Nauman Khan, the President of the Pakistan Solar Association. “The value of one container is minimum Rs10 rupees and this makes a market of Rs57 billion. This is only the estimate of solar panels and the average market of solar panels is between Rs50 to 60 billion,” he explains.

The numbers from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics back him up. Pakistan’s imports of solar panels was approximately Rs56 billion in fiscal year 2019.

“Inverters, batteries, cables, frames and nut bolts along with manpower is extra cost in the system and if these all are included in the panels the estimated market goes up to Rs100 billion. The market that deals with this import is divided into four sectors which we deal with and these include agriculture, home, commercial and industry.”

“Our market is importing almost 1,000 megawatts from this system in the form of solar technology. Almost 70-80% of import is from China, rest is from Germany, USA, Taiwan, Malaysia, Korea etc. The addition of coal and LNG in the production of electricity has raised the prices of electricity in Pakistan. In these summers when one house would turn on 3-4 air conditioners the consumer will have to pay a bill of Rs40-50,000 per month.”

The question then becomes, why is Pakistan not producing itself? According to Saeed Hussain, the government’s man on the issue, there is no industry in Pakistan which could convert the raw material into silicon which was found in the northern areas of Pakistan.

“Photovoltaic (PV) industry requires silicon, and while our northern areas have ample deposits of silicon, we need industry to convert the silicon raw material into pure silicon and thus we send this material to China. In China, there are four to five huge companies which convert the raw material into silicon and produce PV panels.”

Hussain also added that the inventors of photovoltaic (PV) were Germany and America and when they started working on PV it was an alien thing for all whereas in 1990s they had started installing the solar panels. “When this industry gained boom, China took the lead and now no one can beat China because of the cheap labour there.”

He is not entirely accurate there. Yes, China is the global leader in the production of solar panels, but it is not because of cheap labour. As Tim Cook of Apple stated late last year, “China ceased to be the low-labour cost location more than a decade ago.” The reason companies still manufacture such goods in China is due to the cluster effect: there are hundreds of manufacturers of all types of supplies and equipment – as well as technically skilled labour that these companies need – to produce a complex industrial product like a photovoltaic panel.

However, Hussain and the government are of the opinion that increasing competition in solar installation companies has meant that to remain competitive, companies were doing everything to bring down their prices, and the easiest way to do this is to import sub-par materials.

“With a difference of a few pennies the companies sell the material which is again substandard. If the importers maintain the quality of the product, then this is a brilliant business in Pakistan,” he says. But the if remains a big one.

Hussain claims that the imported material used in the installation of solar electricity systems was mostly of sub-standard quality. “When our businessmen import material they overlook the quality of material. Sometimes, they import junk or B, C and D class material which is rejected by other developed countries. In 2018-19, all of the imported material was substandard, he says. “Those companies install these materials and after some months the solar system gets problematic and does not support current due to which the system collapses and the money of the consumers goes down the drain.”

But then is the government going to do this, because rocking back and throwing its arms up in defeat is not the most ideal way to deal with it. “At the government level, we looked for a solution to stop the import of sub-standard material to Pakistan,” Hussain explains. “For this we started a project with South Korea in Quetta, and also established a lab that tests all the imported panels.”

This project was worth Rs1,200 million, and in two to three years another such lab is slated to be established in Islamabad. There are 17 to 18 tests of PV panels which will be done in these labs, and only the good quality panels will be allowed to be installed so that people do not face any financial loss.

Naturally, Nauman Khan over at the Pakistan Solar Association has not been too keen on this idea. According to him, the import of substandard material has been going on since 2006. Pervez Musharraf had made the policy according to which the material from 2006 to till was being imported was exempted from import taxes. From 2006 to 2010, it was a very small market and the clientele was the NGOs sector or relatively remote areas, but it was after 2010 that this market got a boom and then became commercialised. This, Nauman says, is where the Afghan traders entered into the market of Pakistan.

“There were two issues associated with this. The first was that in Afghanistan there was a duty on import of solar material, and in Pakistan there was no import duty. Until 2010, the market had grown to 100MW with a worth of Rs10 billion,” Numan tells us. “This is where traders from across the Durrand entered in this business.”

These Afghan businessmen had previously established links established in China, and it was from there that they first started bringing in the sub-standard material. “That material was being sold by tempering and with stamps of various brands. At that time (2010) we were importing material from the brands which was costing us Rs70 per watt and we were selling it for Rs90 per watt,” says Nauman.

“On the other-hand, the Afghans were importing the low quality material at the rate of Rs50 per watt and selling at Rs70 per watt in the market. This factor gave a setback to us, while the Afghans evolved the market as they took the solar technology business to a level where we would not have taken it in 10 years doing everything by the book.”

It was here that the foundation was laid for the Pakistan Solar Association, of which Nauman is now President. And when Ishaq Dar imposed taxes on the import of solar items in 2014, the association was officially founded and decided to fight for the solar industry in Pakistan as it had first been established.

“We decided to struggle for the waiver of import duties and worked on the standardization of the imported material. In 2015, we developed a program with collaboration of USAID and GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit). German Solar Association and American Solar Association held training sessions with us and transferred the technology for us,” Nauman touts.

Later on in 2016, the association conducted a value chain analysis. It recorded the number of off-grade and on-grade materials, along with the locations where it was being used. They also worked towards sending engineers for training in Germany, as well as training installers in the local market. In this way, quite conveniently, Nauman puts the blame for substandard materials squarely on the shoulders of the enterprising Afghan element in Pakistan’s solar industry history, and gives all the credits for material regulation on his association.

“Now it is not possible that substandard material is imported in Pakistan. We also got the authorization from the government to check the material and in case of any substandard material proposed an action on it whereas we have recently already pointed out substandard materials which were caught by the government,” Nauman Khan said.

Covid-19 reality check

On a sombre ending note, we can talk all we want, but the solar industry is as much a part of the economy as something else. And as with everything economic, the Covid-19 pandemic has this sector feeling the heat too. And even though it should be something that happens sooner rather than later, as things stand, solar panels are a luxury, not a necessity, and thus not getting any business.

“Due to COVID -19, a loss of 10 to 15 billion has been faced by the solar market. I am personally doing a 100 megawatt project for the government and its few documents are delayed due because things just have not been signed over the past couple of months,” says Nauman. “We have an American investor as well for this project who is waiting for the approval of this project. This will be an investment of rupees 10 billion of 100 megawatts and this will be in Punjab. This arranged investment of 10 billion is not being materialized because of COVID -19 and we do not blame the government for this as it is very effectively looking after the corona issue. On the other hand during this time if the investor backs out it will be a loss.”

batteries increase the cost by 100%. no one is offering a fully off grid solution with large batteries like a tesla powerbank.

The article is very well researched one and give an insight in this issue with ease to understand. 👍

The sub standard material issue is a serious concern for new entrants. Its a costly ordeal. I wish with a little more cost we can get atleast the quality which gives a decent return on the investment in the long run.

Is there any possibility in future in getting a quality pannels in pakistan? And how can we determine the quality? Esp whn all imports r of sub standard material till 2018-19…..

Reference your subject cited above, it is stated that gov’t can”t takes interest on energy sector. Usually, it is difficult to enhance electric source without collaboration of provincial governments. It is not possible on current environment. NAB is going out of way to issue warranty of arrest is plight of political chaos. Nothing gain until united.

In your next article plz herald upon the feature of on grid govt policy for solar energy, and their comparison with other places. And what improvements and incentives can catalyse the solar energy boost in pakistan

Good article 10kw solar system

Dear Mr. Shahab

I just read this article while researching for approximate investment cost for production plant of Solar Panels with state of the art technology. Do you have expertise in that aspect as well including input on government policy support and future outlook in terns of per watt production prices vs Imported panel prices.

Energy 2000 Pvt. Ltd is a premium solar solution provider, offering state-of-the-art and comprehensive solar systems in Karachi and other major cities of Pakistan. By harnessing solar power, our experts provide affordable and viable solar system solutions to the residential, commercial and industrial sectors in Karachi and other cities. Our diverse product range, extensive experience in the industry and a strong project portfolio make us premium solar solution providers in Pakistan.

Thank you for writing such a great article and well researched. I got lots of useful information.

Very informative. Thanks a lot 🙂

Comments are closed.