In August, 2019, Profit profiled two new venture capital funds targeting Pakistani startups. Indus Valley Capital and i2i Ventures had just entered into Pakistan’s startup ecosystem with a cumulative $20 million in committed capital to invest in startups.The premise of the article was a simple question, “is there enough deal flow?”

More than anything, the feature was an explainer detailing the problems faced by investors finding startups in Pakistan. It was a litany of the central problems that plague Pakistan’s startup ecosystem. Chief among those problems is that there just are not enough promising startups in Pakistan to invest in. While there is no dearth of startups looking to raise investments, how many of those are really worthy being invested in?

There are a few startups that have raised serious funding and among the startups that according to sources is close to finalising an undisclosed seven-figure dollar investment from the founding team of a major UAE based e-commerce platform is the Lahore-based, online grocery shopping and delivery startup, GrocerApp. The new round of funding will help scale its operations on the back of impressive growth.

GrocerApp is an online grocery delivery service that allows users to select household grocery essentials on its application or website from a wide range of the most in-demand products. They then deliver your products to your doorstep the same day, saving you your time and the inconvenience of going out to do groceries.

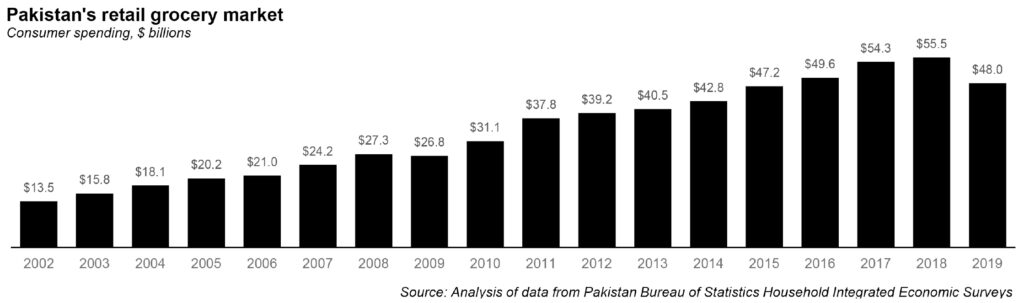

There is much to like about GrocerApp. The idea is simple and targets a large market – the largest segment of consumer spending comprising over $48 billion in 2019, according to Profit’s analysis of Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. It is also largely an untapped market as far as tech-enabled solutions are concerned.

However, it is not the most revolutionary service in the world. So what sets GrocerApp apart, and how did they manage their early success? We look at what GrocerApp’s business is about, the market it operates in, how it has grown over the few years it has been operational, if the business is defensible, and its plans post funding.

Just another startup?

Much can be inferred about what the future of a particular business would look like from its founders. One of the major complaints that leading investors, entrepreneurs and venture capital firms have with Pakistan’s startup ecosystem is how brilliant ideas in Pakistan do not have brilliant entrepreneurs to execute them, either from a lack of experience or education, or simply because of a lack of vision or initiative.

The founders of GrocerApp, Ahmad Saeed and Rai Bilal, allay some of these broad concerns. Finance graduates from the Lahore School of Economics (LSE), both founders also have experience working in a successful startup, having been early employees at PakWheels, one of Pakistan’s highest valued tech startups.

Both Ahmad and Bilal left PakWheels in 2015, the former leaving his position as Chief Operating Officer (COO) after six years at the company, and Bilal – who also holds an MBA in supply chain management from Scotland’s Robert Gordon University – as head of operations after four years at the company. Together, the duo wants to use their experience and talent to change the grocery shopping experience in Pakistan.

But an indicator more important than education and work experience that marks Ahmad and Bilal as successful entrepreneurs who can execute on an investors money is their success in scaling and sustaining a business. Not only has GrocerApp avoided becoming a fad that quickly becomes a thing of the past, it continues to grow, and perhaps more rapidly now that the co-founders have their skin in the game.

“We started GrocerApp in early 2016. It started because of an inconvenience that I was facing in grocery shopping. It was becoming a challenge for me at my household,” says Ahmad, explaining the beginnings of the company. “If you belong to the middle class, you cannot afford a chef or a driver or multiple servants. You have to take care of it yourself and grocery shopping becomes a pain when you have other things to worry about, like your work.”

“I started looking for online grocery services for my own consumption but I could not find a good, reliable service. I was facing that challenge and when I asked other people, they were facing a similar challenge and that was the start of GrocerApp.”

Sizing up the market

GrocerApp has been in existence since 2016 with initial funding of $12,500 dollars from co-founders Ahmed and Bilal, followed by a number of small angel rounds which brings the cumulative total investment in the company to about $500,000. With a new round of funding on the cards, GrocerApp is poised to establish itself as leader in grocery delivery.

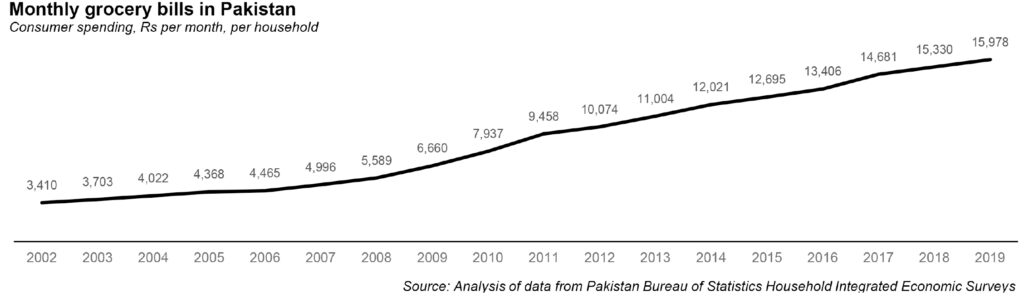

Pakistan’s retail grocery market is the single biggest component of total consumer spending. According to Profit’s analysis of Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) and Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), consumer spending on groceries was approximately Rs6,540 billion ($48 billion) in Pakistan, approximately 38.5% of total consumer spending.

This market has been growing at a relatively average rate of 12.7% per year between 2002 and 2019, a period during which overall inflation has risen by an average of 8.1% per year.

At present, GrocerApp’s operations are concentrated in Lahore only, with eventual plans of scaling to other larger cities in Pakistan. Both incomes and consumption levels are higher in Lahore than in the country as a whole. Profit’s analysis of PBS data suggests that while the city accounts for 5.4% of the country’s population, it accounts for 6.9% of total grocery spending in the country.

The data suggests that the Lahore grocery market was worth Rs451 billion ($3.3 billion) in 2019, one of the fastest growing ones in Pakistan, a substantial and attractive market for many internet entrepreneurs to jump in and try to disrupt the market, and get a slice of the pie in the process.

And as it turns out, there are not any significant online players in this space, and GrocerApp has had a significant head start early on in the game. Ahmad and Bilal have the opportunity to capture a major chunk of the market if they play their cards right. Market size is a big part of what determines how much a startup should be able to grow, and growth is what investors ahead would be concerned about.

“We are growing quite significantly for the last one year. Even pre-corona, from March 2019 to March 2020, we grew at about 30% month on month. Right now we are making a few hundred thousand dollars in Gross Merchandise Value (GMV),” Ahmed says.

The company declined to share its revenues publicly, but did confidentially share some of that data with Profit, which demonstrated exponential growth over the past three years, with GMV growth rate between 2018 and 2019 approaching 121%, albeit from a very low base.

But revenue in itself means nothing if it does not tell you how much cash in profits a business is generating. So while GrocerApp is growing exponentially, it does not mean this growth is profitable. Yet there is a catch even to this caveat, which is that even though GrocerApp might not be making any profits as of now, it seems to be on the track to do so.

Ahmed confirms as much to Profit, disclosing that GrocerApp is contribution-margin positive, meaning that each extra unit it sells is profitable, even though the company itself does not yet make a profit. Favourable unit economics is another key success criterion that venture capital investors look for in a business, particularly in the current, capital-constrained environment.

Globally, grocery retail margins are extremely thin and among the lowest in the economy. It is thus difficult to hold it against GrocerApp for making thin margins. It is in the nature of grocery retail that profits come late into a business because you can only scale on enormous sales volumes, which essentially means you have to keep spending on the business until the required volumes are achieved and pushes the company into overall profitability.

And GrocerApp is now on the verge of achieving that scale in business, that each order that it delivers to a consumer now is profitable.“Contribution margin positive means that on each order we deliver, we make money. We are not burning money anymore. Costs associated with logistics, fulfilment and packing, everything is included and the margin that we make out of it is positive,” Ahmed tells us with pride.

“We do have a bit of overheads like human resources, management, fulfilment facilities and all. So, the company overall has still not achieved break-even but at the trajectory we are growing, we are hopeful that within the third quarter of 2020, we will achieve it. We are very close to breakeven and it would be remarkable for a startup to achieve breakeven at this scale.”

Now, because the margins are extremely thin, Ahmed says that they focus on increasing efficiency to improve margins to attain profitability even more quickly and that requires optimising every part of the supply chain, fixing every nut and bolt.

Ahead of the competition?

While there is no serious tech startup in Lahore that GrocerApp worries about, because, frankly, there were not any until recently, things heated up a little after the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns that ensued, which led to a sudden collapse in grocery shopping at conventional retailers and hypermarkets.

A decrease in grocery shopping at physical retail outlets meant that the target market for online grocery shopping and delivery swelled and to seize the opportunity, startups that had logistics as their core business successively ventured into grocery delivery. Uber, Careem, Cheetay, FoodPanda, Airlift: everyone and their uncle in the startup ecosystem moved into grocery delivery.

These companies entered with varying models and different value propositions. Some moved in with the dropshipping model, meaning that they would pick up groceries from stores and deliver to consumers. Some entered with their own warehouses to hold inventory and serious amounts of funding. Airlift, for instance, announced raising $10 million during the pandemic to scale its mass transit and grocery delivery operations that includes its warehouse in Lahore, though the company did not disclose how much out of the $10 million would be spent on grocery delivery operations.

More startups entering grocery delivery could mean trouble for GrocerApp. But, Ahmed believes their head start of a couple of years in the business could be a competitive advantage.

Secondly, relative to the number of startups entering into grocery delivery, the founders believe that the market size is still very large and even with so many players entering the same space, GrocerApp’s delivery orders during the pandemic still shot through the roof.

Besides these startups, GrocerApp already competes against large brick-and-mortar mass retailers like Metro, Carrefour and Al-Fatah that are also moving towards the ‘click-and-mortar’ model – where traditional retailers combined online ordering with the ability to pick up orders in physical stores – aggressively. They are big enough to theoretically rip GrocerApp apart from the market very quickly, but might not be able to do so. Or at least, that is what Ahmed thinks.

“We don’t see them as a challenge. The reason being, grocery delivery has a few pillars to measure prospects of success against a competitor. Firstly, there is retail, which these giants are actually strong at by virtue of being in the industry for a long time. They know what to buy, when to buy at what price to buy. But that does not mean we will not catch up. We are building our capacities along those lines,” Ahmed explains.

“The second pillar is logistics. How to efficiently pack and deliver an order and things like that,” he adds. “Grocery delivery is a very unique business that has challenges of its own. You have perishable items, items that cannot survive in heat. So we shifted towards larger vehicles. We shifted towards rickshaws and that sort of vehicle. Right now we have a fleet of around 50 riders and we have divided Lahore into multiple zones and riders are assigned to different zones. Some zones have a single rider whereas busy zones have multiple riders.”

But most important among them is technology, Ahmed says, and they are big on tech while their competitors are not. “Building up the technology from placing of the order to your website to backends, your warehouse technology, your logistics technology, there is a huge technology play that comes in. An order that needs to be delivered, how to deliver that order, how to pack it, where to keep it, there is a lot that technology can do,” he says.

Traditional brick-and-mortar retailers have been under threat for sometime now. A 2018 report by McKinsey and Company warned of a “monumental force” disrupting the retail grocery industry, and underscored that if brick-and-mortar grocers do not act, they will be letting $200 billion to $700 billion in revenues shift to discount, online, and non-grocery channels, and putting at risk more than $1 trillion in earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

And a monumental force that the report outlined are new technologies such as those that enable the ecosystems of Alibaba and Amazon. “When the dust clears, half of traditional grocery retailers may not be around,” read the report.

Technology makes processes efficient. From placing an order to packing and logistics, as Ahmed pointed out, processes can be made efficient by technologies that the startups are well-versed at, while traditional retailers are not. They are focused on retail while the startups are focused on technology. GrocerApp is able to deliver orders on the same day, while retailers like Metro or Alfatah will take a whole day or two to deliver those orders.

“By virtue of incorporating technology in our processes, we are very strong on logistics as well. We are strong on marketing as well. We know how to leverage technology to make our marketing stronger,” he says.

By candid admission of a source at one of the big brick-and-mortar mass retail chains, their technology stack and processes are antiquated, which means that there are inefficiencies in their model and eventually their online sales are low. And, to substantiate that, Profit looked at the number of the e-commerce sales of the said retailer, which from a single store were significantly lower than the revenue numbers for GrocerApp, although the combined e-commerce revenue of all the stores of the said retailer in Lahore were almost the same as GrocerApp.

And being strong on tech also means that GrocerApp’s application and interface tend to be better than it’s click-and-mortar competitors’ applications, which Ahmed says can be compared easily with other applications.

It is not just these pillars that Ahmed mentioned that put GrocerApp ahead of its competition. There are some cost advantages as well that GrocerApp has. For instance, all the fulfilment by GrocerApp is done at a fulfilment center, located strategically near Lahore’s Peco Road, which is essentially a warehouse that has a significantly lower cost per square foot compared to the mammoth retail outlets of Metro, Carrefour and Alfatah with fancy facades.

Moreover, since GrocerApp only focuses on delivery, it can establish additional fulfilment centers in the city over cheap land, and at locations that make logistics more efficient. The warehouses delivery business do not need to be fully air conditioned either. For the brick-and-mortar store, since they have walk-in customers, their outlets would have to be established at locations that generate greater footfall. That means these outlets would mostly be located at prime locations that are pricey real estate, which would also be fulfilment centres for online deliveries and thus would overlook logistical ease.

Positive contribution margin is a scale that has come after a significant wait, and this milestone is what its founders believe makes GrocerApp’s business defensible against new competition such as new online grocery startups.

While the startup would be trying hard to scale itself and attain profitability – itself a difficult prospect because the margins are extremely thin – GrocerApp would have attained profitability that would give it enough cash from the company itself and the larger rounds it would raise to keep its competitors from moving ahead in the game.

Against the backdrop of GrocerApp’s robust operations and growth potential, new funds will fuel its growth and attain profitability quickly. Though Ahmed says they could have attained profitability on their own, without even raising funds, it would only make the process quicker with a new round of financing.

The new investment (once finalised) and its utilisation will eventually set the ground for a much larger round that would be used to scale GrocerApp’s operations to five more cities.

“These funds will help us crack the model even further. It will also help us set up operations in a way that would enable us to handle operations in multiple cities from Lahore. We would figure out how to scale to another city and maintain fulfilment in another city while not even being there. We will be looking to raise a larger Series maybe by the middle or early next year,” he says.

As for the valuation, GrocerApp wants to keep it undisclosed.

As mentioned earlier, an impetus has been provided to grocery sales by the pandemic across the globe and GrocerApp says it has witnessed a huge surge in orders during the lockdown period. That has also exposed users to the convenience that technology brings with it.

Consumers now, because they have seen the convenience of e-commerce grocery, even if unwillingly, might be more inclined towards it post-pandemic, especially if they get used to it. This would automatically mean increased users on online grocery platforms. And only those that leverage technology better would be able to grow and even dominate the space.