On the 9th of December, the once sleepy hill-town of Murree was declared a calamity hit after thousands of cars were stranded out on the roads because of an influx of tourists coming into the area. Before rescue operations could be launched, at least 23 people including children had perished in the night.

The outrage that followed the tragedy has been as impassioned as it has been unfocused. While blame was naturally ascribed to the inefficient response of the local and provincial governments, a lot of the backlash focused on the fact that local hotels began charging exorbitant rates from stranded visitors and there also began a widespread call to boycott Murree as a tourist location.

However, there is a much more critical lesson that needs to be taken from the tragedy at Murree. Only a few days before the incident, information minister Fawad Chahudhry had bragged that the arrival of more than 100,000 cars in Murree was an indicator of economic prosperity and showed that people were not under any great financial stress. The statement did not age well (to put it mildly) but it tells us something – the government approach towards tourism in the country has focused simply on getting people both local and foreign to travel and experience Pakistan without much care as to how these tourists should be managed.

Tourism is a complicated subject that takes a lot of thought and planning. The number of tourist destinations in Pakistan have increased over the past decade, especially with greater road access along the Karakoram highway. But other than connectivity and access it is worth looking at what plans have been put in place in terms of sanitation, real estate development, energy, traffic management, resources, and public awareness.

Tourism in Pakistan

Pakistan’s tourism potential has long been known for a long time. Dogged by security issues and political instability, it has been unable to attract a significant amount of foreign tourists even though it has received a lot of media attention as a hidden gem. Different governments over time have been drawn to this idea of turning Pakistan into a tourist hub and some steps have been taken in terms of connectivity and accessibility of remote areas, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

Tapping Pakistan’s tourism potential has in particular been a pet project of incumbent Prime Minister Imran Khan. His government came in with the aim of building four tourist resorts a year to reach a total of 20 by the end of their tenure. All to promote tourism in the country. According to the 2021 report of the World Travel & Tourism Council, travel and tourism contributed $8.8 billion, approximately 2.9% of total GDP of Pakistan, in 2017. By 2019, the total GDP contribution of tourism to Pakistan was $15 billion which accounts for 5.7% of the total GDP. However, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, this growth fell significantly in 2020 by nearly 25%, falling to $11.6 billion, or 4.4% of GDP. Similarly, jobs in the tourism industry fell 11.1% from 3.45 million in 2019 to 3.63 million in 2020. Most significant to these figures, however, is that the major contributor in this is Pakistan’s domestic tourists. In fact, domestic spending on tourism accounts for 91% of total spending, and foreign tourists bring in a mere 9% of the revenue of the tourism and travel industry in Pakistan. Of this, 93% is leisure spending on travel and tourism and only 7% is for business.

This then means that the majority of the demand for tourism in the country comes from within. Nearly five million domestic tourists travel each year across Pakistan. But for all of the natural potential that Pakistan has, it lags behind in some very specific areas. According to the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index developed by the World Economic Forum, Pakistan lags in all key sub-indicators with the exception of price competitiveness, which is only the result of the depreciation in the rupee.

Out of a list of 141 countries, Pakistan is 130th at having an Enabling Environment, 138th on Safety and Security index, 102nd on the Health and Hygiene index, 138th on the Human Resource and Labour Market index, 123rd on Travel and Tourism Policy and Enabling Conditions, 120th on Prioritisation of Travel and Tourism by the Government, 107th on Tourism Infrastructure, and 141st out of 141 countries on the Environmental Sustainability index.

What happened in Murree?

The problems that have been described above have plagued Pakistan’s domestic tourism industry forever. There is very little care for environmental sustainability, sanitation is not taken care of, real estate development on the outskirts of places like Murree is rampant with complete disregard for utility provision like sewage and power. The influx of tourists can go in the hundreds of thousands in peak season and finding rooms can be increasingly difficult.

Murree is still Pakistan’s most visited and well known tourist destination in the public imagination. What happened in Murree shows the same problems that have been described by the different indicators in which Pakistan ranks badly. In an article for Dawn, Dr Omer Mukhtar Khan, author of the recently published ‘Once Upon A Time in Murree’ argues that “part of the reason is our collective apathy when it comes to strong urban governance and sustainable environmental practises. Murree has been our top most visited resort since independence and while the elite may have found other places to spend their vacations, the majority of Pakistanis did not have many options and stuck to this beautiful colonial hill town for their brief holidays.”

‘Murree continues to be run from Lahore with very weak local government as elsewhere in the country, limited building regulations leading to monstrous hotels and apartments cropping up, poor waste management systems with trash everywhere, smelly sewage flowing all around and an unregulated and predatory hospitality industry doing the rest in destroying this only mainstream tourist resort for Pakistanis. There is also limited focus on traffic management as well as an effective communications system to inform the public at large about any weather warnings,” he went on to write.

This is where our original point comes back in – tourism is not an easy sector to develop. requires development of infrastructure like power, telecommunication, water supply, roads, sewage and sanitation and some associated sectors like travel items, sports equipment, medicines, and cosmetics.

Take simply the issue of sewage and solid waste management as an example to try and understand the level of detail that needs to go into developing tourism. Every single industry has a particular wasteful by-product. In the case of the tourism industry, that by-product is solid waste and sewage. A 2018 joint study by the National University of Civil Engineering in Vietnam and Okayama University of Japan, found that on average in tourist hotspots the amount of waste produced per day by a single guest was 2.28 KG. The study, which looked at 120 hotels in tourist hotspots, sampled waste produced from all departments of the hotels such as from the rooms, garden, restaurants, kitchen, laundry, offices, stores, repairing stores, and from other services. Vietnam, which has over the past few years been developing as a tourist destination, has had a fraught history with managing the waste from their tourists. A different study published in ‘The Journal for a Sustainable Economy’ shows that the tourist destination of Hoi An City, which gets more than 3 million visitors a year, generated around 15080 KG of waste daily.

The amount of waste that can accumulate when a tourist destination’s population swells during peak season is one of the top problems in managing the growth of the tourism industry. If hundreds of thousands of people are visiting an area like Murree at a time, the size of the solid waste problem has to be measured in the tonnes. Going by the earlier mentioned study, if a single guest is producing just 2Kg in solid waste and sewage per day,and you have 100,000 visitors in Murree, that is 220 tonnes per day of waste. That translates to 6600 tonnes of waste per month in peak seasons.

The impact can be an urban management disaster as well as an environmental hazard. In 2017, environmentalists raised concerns after hundreds of fish were found dying in Rawal lake because of contamination. The main reason for the contamination was the flow of sewage in the streams of Murree and its adjoining areas into the Korang River which discharges into Rawal Lake. A Dawn report on the issue said that “the Punjab government has yet to take action for stopping sewage from Murree and its adjoining areas from ending up in the lake as it wanted the federal government to install a treatment plant, claiming that the 12 kilometre area around the lake fell in the limits of the CDA. Though billions of rupees are being spent on the development of the hill station, no steps have been taken for installing a sewage treatment plant in or around Murree.”

In a 2015 report by the government, the system of sewage in Murree was “non-existent. “At present no system exists for the drainage of domestic/commercial sewage and storm water in the Murree City area. Sewage is disposed of through lined / unlined drains constructed by local bodies and these drains either disposed of on the hills directly or terminated in the natural hill torrents around the inter periphery of the city. The sewage either seeps down in the crest of hills or contaminates the water bodies in the hill torrents. Especially at the western side of Murree sewage flows upto the Haro River and contaminates its water. Seeping down sewage and storm water in the hill causes frequent landslides and contaminating hill torrents,” read the report.

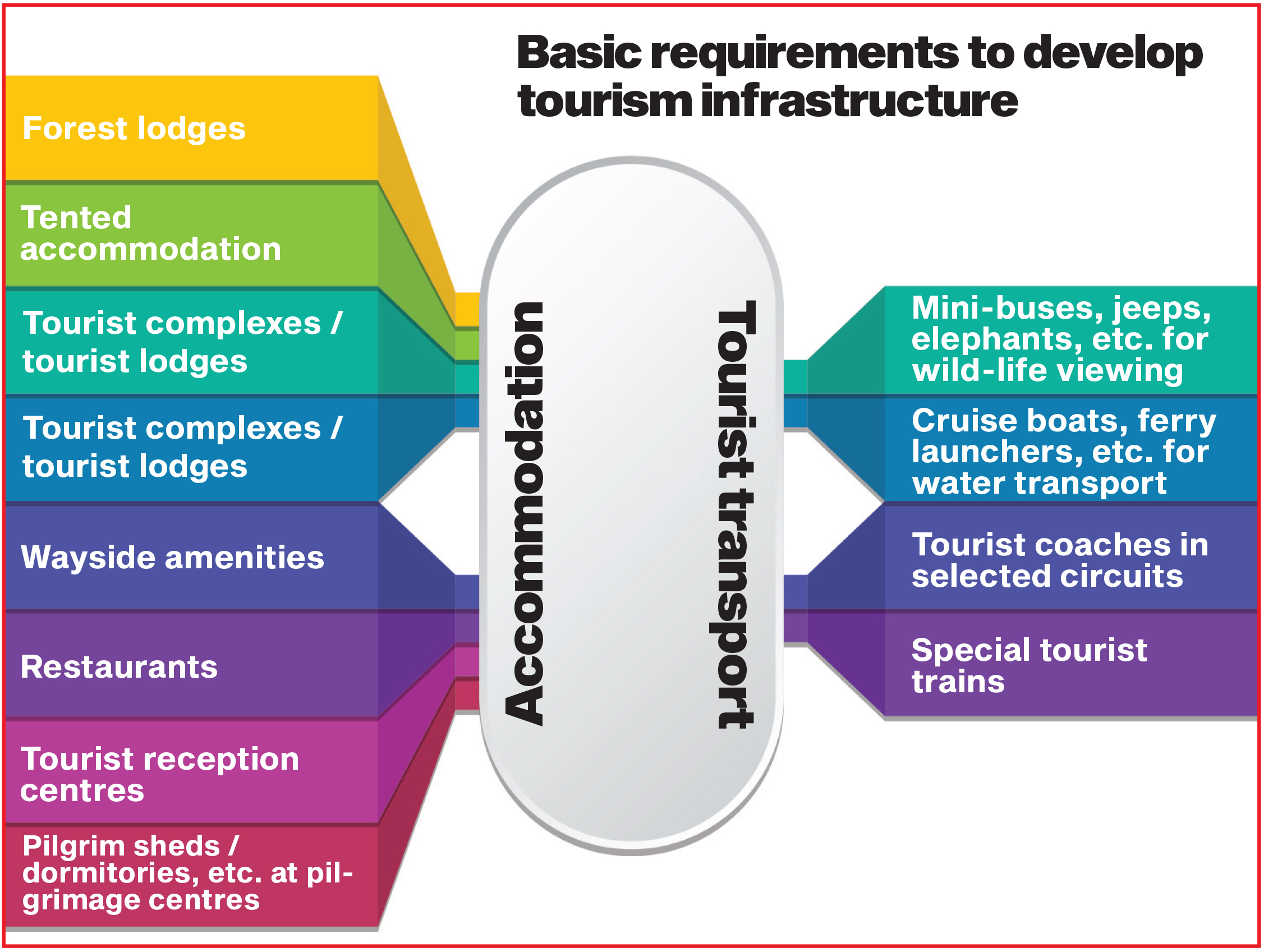

The infrastructure for tourism thus includes basic infrastructure components like airports, railways, roads, waterways, electricity, water supply, drainage, sewerage, solid waste disposal systems and services. Moreover, facilities like accommodation, restaurants, recreational facilities, and shopping facilities also come under the ambit of Tourism Infrastructure. Planning for sustainable development of Tourism Infrastructure, therefore, involves the integrated development of basic infrastructure and amenities along with all the tourism facilities in a balanced manner. It needs thoughtful planning and dedicated execution.

In the case of Murree, the development of the hill-town has come with not just colonial baggage but the disadvantage of being administered remotely from Lahore as part of the Punjab. While Murree is the largest tourist destination in Pakistan in terms of inflow (particularly domestic inflow) it is worth looking at how other tourist destinations are being developed in Pakistan, such as Gilgit-Baltistan, which has seen more interest after accessibility to the region has increased through the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the Karakoram Highway.

The Gilgit-Baltistan example

In April 2021, Prime Minister Imran Khan announced the historic five-year development package worth Rs370 billion for Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) during his visit to Gilgit. After the inauguration of some projects of the Special Communication Organization (SCO) in Gilgit, the prime minister said that the government was starting with a package of Rs370 billion to be spent over five years and that never before had such an amount been spent in the area.

The Rs370 billion development plan includes PSDP funding of Rs275 billion in three years with an average Rs55 billion per year. At least 18 new PSDP projects are included in the package with the cost of Rs130 billion. Whereas 11 ongoing projects of PSDP of Rs31.2 billion are also included in the package. Besides, at least 2,114 ongoing projects of the Annual Development Programme (ADP) of GB worth Rs113 billion are also included in the development package.

The major focus of the package and the projects is supposed to be developing infrastructure in Gilgit-Baltistan to make it an attractive location for tourism.

For tourism in particular, skills development and training related to tourism, Rs6 billion have been allocated, while Rs17 billion will be spent on projects relating to health and education initiatives. However, other than health and education, the allocation of the money is supposed to be in the general interest developing tourism in the area. As part of the package, there are five road projects worth Rs35 billion, two big water projects of Rs8.5 billion including a water supply scheme for GB and a sewage and sanitation scheme for Skardu. There are also various projects such as incubation centres for promoting business and entrepreneurship, flood protection structures, enhancement of biodiversity and aqua systems, network expansion of 3G and 4G services in the pipeline.

All of these projects from sanitation to mobile connectivity are critical to any sort of tourism economy developing in the region. According to data gathered in the last three years, the flow of domestic tourists in Gilgit-Baltistan is 86% while the rest is foreign tourists. Back in 2012, the government of Gilgit-Baltistan had tried to identify some of the problems that were resulting in poor inflows into the area for tourism.

In a presentation given by Imran Sikandar Baloch, then Secretary Tourism, the problems started from the condition of the Karakoram Highway, which was in poor condition with no alternative road available. If the highway was choked or if there was a particularly bad landslide, there would then be the issue of long pileups in an environmentally volatile and harsh area.

And the infrastructural issues did not end there. Unpredictable flight scheduling and the woes of PIA bookings means that by-road is the only sensible way to approach the issue. The centralised issuance of permits and conduct of briefing and debriefing in Islamabad is also an issue in addition to the lack of tourist facilities at the tourist attractions and lack of skilled manpower despite a reasonable literacy rate.

The presentation also highlighted how there is a lack of authentic tourism related data or any baseline study by reputed parties, a lack of online information, reluctance of major travel insurance companies to insure foreign tourists, the absence of a tourism policy, mushrooming growth of civil structures due to absence of zoning laws, and no tangible investment policy.

Since then, a lot has changed. For starters, the Karakoram Highway as part of CPEC has been cleaned up and made accessibility to the region much easier. In terms of getting there, the Skardu airport has also improved. Only recently, in December 2021, Prime Minister Imran Khan inaugurated the Skardu International Airport and Jaglot-Skardu road during a day-long visit to the region. The airport in Skardu was previously only operational for domestic flights, and the Prime Minister promised that if Switzerland could generate $70 billion from tourism then “we can make at least $30-$40 billion from tourism just in GB”. Meanwhile, through the Rs 370 billion package that was mentioned earlier, the government wants to address the issue of a dedicated workforce through skills development programmes.

Progress has clearly been made and the number of tourists coming into the region has increased over the past few years, especially since the paving of the Karakoram Highway. Two major communication projects included in the package, including Astore-AJK Shuntar Road (connecting GB with Punjab via AJK) and Gilgit-Chitral Road (via Shandoor) Road (connecting Gilgit with KPK and Rawalpindi/Islamabad) would play the major role in tourism development in GB and adjoining areas. These roads are in addition to the existing highway.

In May 2021, during the peak summer months, Skardu and Gilgit airports on Tuesday saw a massive rise in flight operations, at par with major cities of Pakistan, when nearly 16 PIA flights operated to and from both the cities daily. The airports saw a hustle bustle with flights continuously arriving and departing at the same time.

Getting to GB for tourism has become easier for sure. But is the region equipped to handle such a large and rising load of visitors? Have arrangements been made to first discourage the use of single-use items like plastic wrappers, or safe and sustainable disposal of the sewage that such a large number of visitors will bring? Already pristine parts of the region, like Deosai, are littered with plastic waste. What will happen millions of people start visiting the region over one season? Zoning laws are not clearly implemented, power coverage in the region continues to be low, sewerage and sanitation treatment and disposal is virtually non existent, and other than getting there the tourism process has not become significantly easier in terms of having facilities like accommodation, restaurants, recreational facilities, and shopping facilities.

Case study – Malaysia

The example of Malaysia could be one that Pakistan could look to learn from.

There are, of course, structural differences that make things easier for Malaysia and are important in developing any kind of tourism anywhere. For starters, they have a stable political system unlike in Pakistan. Malaysia also has developed and modernised infrastructure including roads and highways linking different cities, renovated and new airports, international standard car rental system, high-speed trains, reconstructed public transport system (trams, buses, taxis etc.), public internet facilities.

In addition to connectivity, they have also focused on developing shopping centres, tax exemptions on luxury goods and exchange rate management. There is great emphasis on the maintenance of tourist sites, conservation of archaeological sites, renovation and the development of urban areas. The government has also given the private sector representation in policy making and reduced obstacles for international and local investors in Malaysian entities.

Like Pakistan, travel to Malaysia is also cheap and there is a very favourable exchange rate for travellers from developed countries. However, for domestic tourists, there are also strict policy measures for crime prevention, especially in tourist areas and developed outstanding health care systems for tourists. Malaysia has also been successful in promoting education for the development of skilled resources, professionalism, and innovation in the tourism industry – which as mentioned is what is being attempted in Gilgit-Baltistan and other regions as well.

The government of Malaysia partnering with private agencies for production of telegraphic imagery including movies, documentaries, adverts etc. for the branding of Malaysian tourism outside of international borders including channels such as National geographic and discovery channels. The entire “Malaysia Truly Asia” campaign in 1999 and “Visit Malaysia (VMY) 2014” were both incredibly popular and successful marketing campaigns that brought serious tourist attention towards the island nation.

They have also encouraged tourism activities such as amusement parks, casinos, races such as the grand prix and formula one — essentially, it is not enough to be just scenic. There need to be things to do.

What are the lessons Pakistan can take out of this? That the government should focus on encouraging more activities related to tourism and focus on creative tools for tourism development based on local resources, such as arts and culture, local wisdom, history, and archaeological sites. Another critical factor would be developing rapid public transportation between tourist areas and cosmopolitan cities for better linkage and accessibility. In Pakistan in particular, there is a dire need to Increase patrolling and crime prevention techniques for more security. It will be vital for the government to show more concern about low-carbon tourism, and they should show more concern about law enforcement to preserve the natural environment and to increase awareness about eco-tourism in the society.

Conclusion

The tragic events in Murree must never be allowed to happen again. Over the years, our tourism infrastructure has failed us. There has been a complete disregard for planning, no focus on developing areas and spaces for domestic and international tourism, and very little attention given to risk mitigation and disaster management. With the government banking on tourism being a big money-puller for Pakistan, there will be the need for some serious introspection after the incident. And this introspection must not simply be limited to the incident at Murree, but making sure we learn from our mistakes and treat the areas we have poised to be tourist hotspots with the respect and care that they deserve.

Sure by developing its Infrastructure Pakistan can do that.

While Pakistan has always extended support to the region at micro and macro issues, the incidents of 1971 left a scar on image of the country. Through exclusive interviews of eye witnesses, authors, politicians, war veterans and rare archival footage, the documentary series traces in-depth and first account narratives outlining the reasons as well as events leading up to the Indian sponsored rebellion in East Pakistan, with the eventual creation of an independent state of Bangladesh.

WATCH THE TEASER 2 JHAUR | WAR OF 1971 | DOCUMENTARY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Jw0B6IxTy4

Good Information

Good Initiate

Hi

Good information

Kindly visit my website i have thousands of free SVG files and free theme, Plugins

freesvg.uk

Very thoughful of you