Pakistan has a long history in global capital markets. The country’s first international bond dates to late 1994 when $150mn was raised at a yield of 11.5%. Since then, the sovereign has tapped global capital markets intermittently over 1994-98, 2004-7 and 2014-17. The most recent placements, six since April 2021, have totalled $5bn including bonds from the government-owned Water and Power Development Authority. This is the most frequent and largest amount raised via Eurobonds over any 12 month period by Pakistan. And this has had an impact on the bonds post issuance performance.

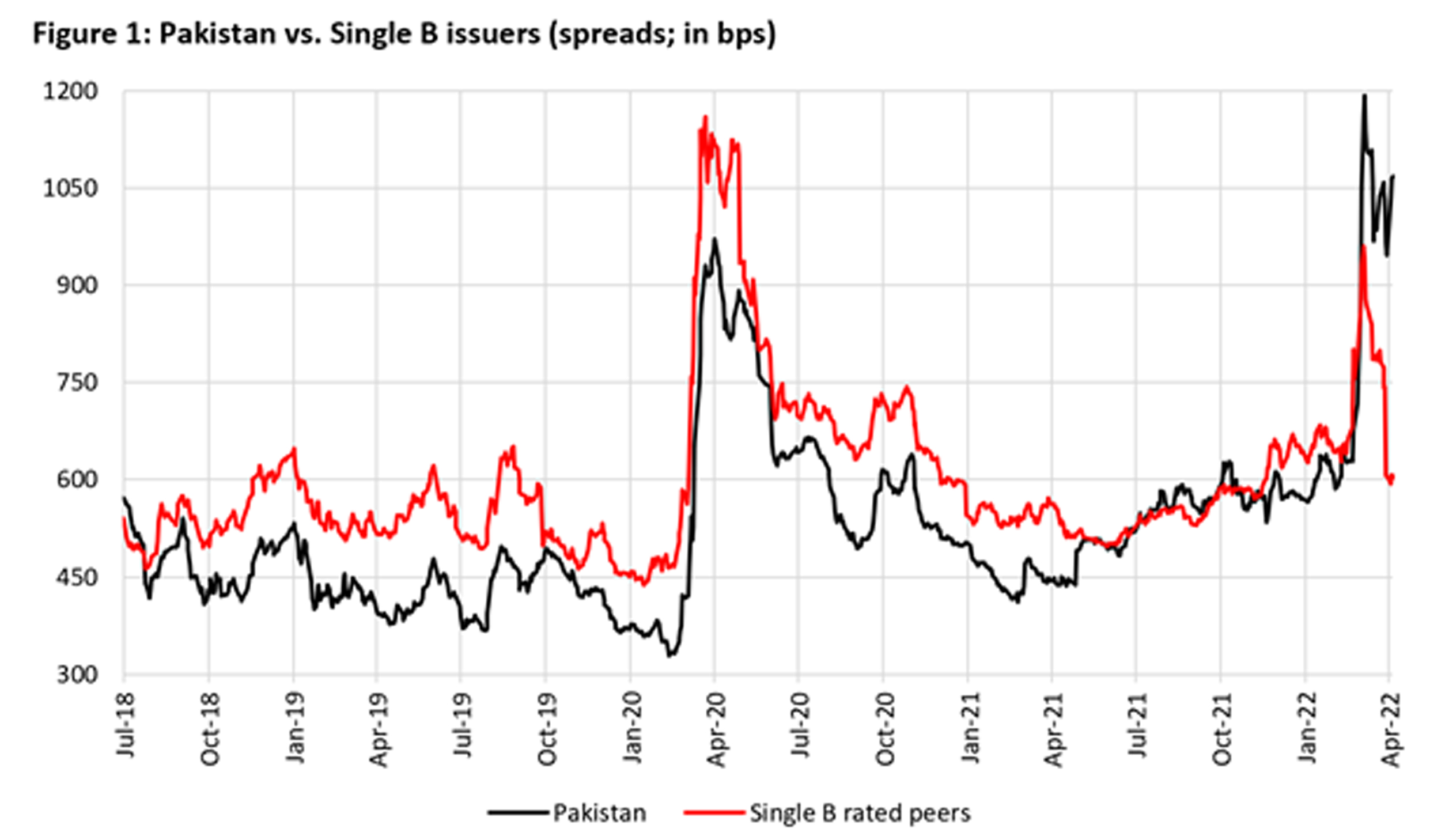

In the recent past, spreads* (a measure of risk perceptions) on Pakistan’s Eurobonds tracked those of similarly rated peers. Till the start of the recent spate of issuance in April last year, these spreads tended to be inside (i.e. lower than) the average for peers indicating better ‘technicals’ and lower risk perceptions. Indeed, there was a small Eurobond float ($4.3bn), which was relatively well held since there had not been any new bonds issued in nearly 3.5 years (between December 2017 and April 2021) while an IMF program provided a reform anchor for investor expectations.

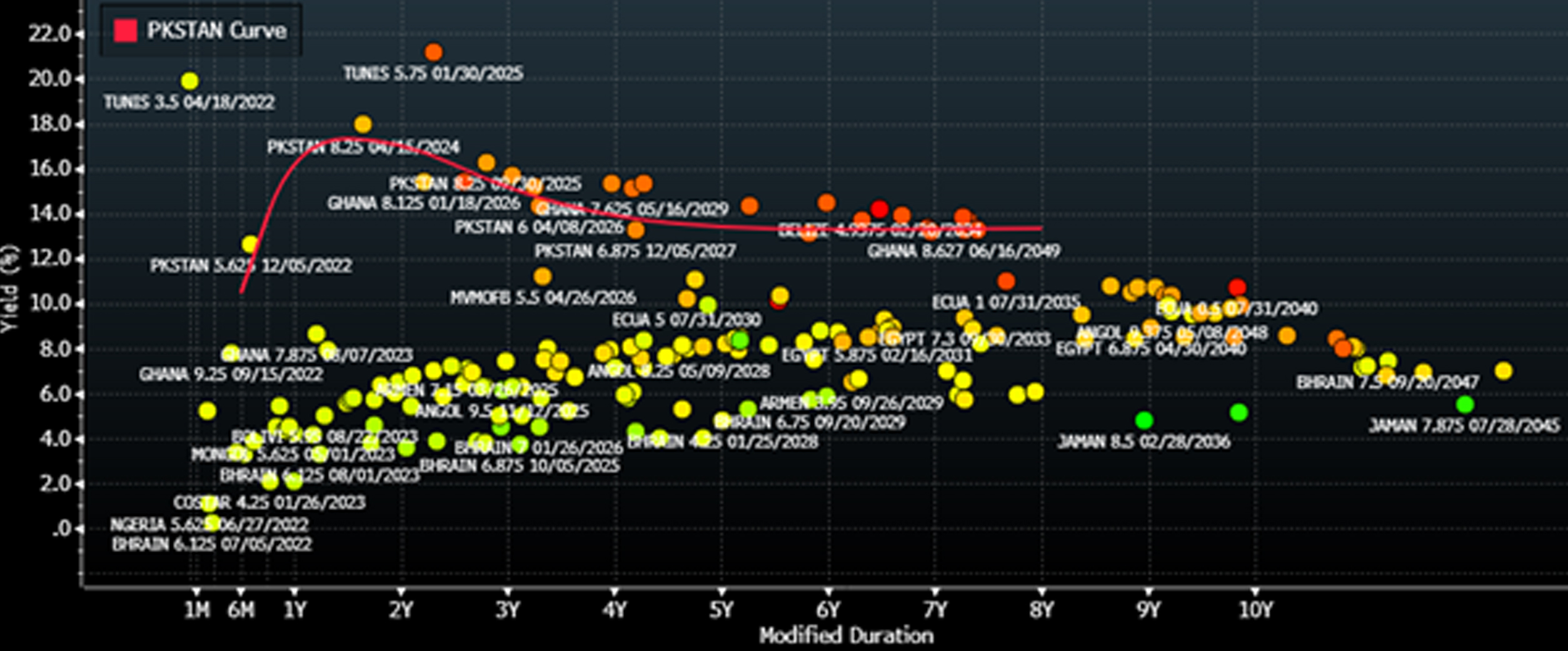

These dynamics have changed in two distinct steps. With significant issuance since April last year, Pakistan’s spreads started trading flat to those of peers (Figure 1). Further, the correlation between Pakistan’s spreads and those of peers has broken in recent weeks – while single B rated issuers have rallied post wides due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, spreads on Pakistan’s Eurobonds have shot up higher. Indeed, Pakistan’s Eurobonds are now amongst the highest yielding within similarly rated countries (Figure 2).

A key driver behind this breakdown are recent political developments and complications they engender for Pakistan’s macroeconomic outlook. Of particular concern is the external sector, specifically the level of foreign exchange reserves held by the State Bank of Pakistan. Since their peak in late August last year at $20.1bn, SBP FXR have declined to $11.3bn as of early April this year. That an average fall of about $1bn a month.

Figure 2: Pakistan’s Eurobond yield curve versus peers

Worryingly, this pace of decline has accelerated in 2022, from $400mn a month over September – December 2021 to $2bn+ a month year-to-date. This headline decline masks even worse underlying dynamics – FXR have fallen despite the $3bn Saudi deposit in December, $1bn from the sukuk issuance in January and about $1bn from the IMF tranche in February.

In the meantime, the IMF’s February 2022 report projects Pakistan’s gross external needs at $30.4bn this year. These estimates include a full year current a/c deficit projection of $13bn for the on-going fiscal year. However, realised data for the first 8 months shows the deficit at $12.1bn. Even if the next four months see this deficit averaging around the February low print ($545mn), the full fiscal year outcome is likely to be over $14bn. Including debt amortization, this suggests gross external needs of $31.7bn for the full FY22. That’s an average $2.6bn a month, or $7.8bn in Q4-FY22 (April-June) on a pro rata basis. Meanwhile, IMF estimates for FY23 gross external financing needs are even higher at $35b+. Note neither number includes potential outflows from Roshan Digital Accounts that total nearly $4bn.

The above raises two concerns for investors. If political uncertainties persist with fresh elections not taking place in the next 6-7 months, how will such large needs be met given the level and pace of decline in SBP reserves. Further, the outlook may not be any clearer even after elections. The outgoing government has made allegations of attempted regime change by the United States, the largest shareholder of the IMF. Meanwhile, current opposition leaders have publicly stated they will reverse the SBP autonomy law passed in January as part of prior actions for the sixth review of the IMF program. Clearly, regardless of who is in power, it seems Pakistan could face a potentially protracted fracture with the IMF. That’s not good news for investors who value political stability, policy predictability and reform commitment.

Perhaps the best hope is that if the opposition wins office, the reality check of being in government prevents a legislative agenda that derails prospects of the seventh program review, already a month late. Without the IMF, political uncertainties will keep Pakistan’s external liquidity under pressure making issuance in international markets prohibitively expensive. In that scenario, preventing further drain of SBP reserves will require bilateral and multilateral donors to step-up. Will they, when Pakistan’s political leadership appears engaged in a virulent protracted battle, remains to be seen.

All said and done, Pakistan’s external liquidity has seriously weakened since August last year. SBP reserves of $11.3bn face gross external needs of nearly $8bn till June. Without inflows, SBP reserves will fall further. That risks ratings downgrades. Given current ratings of B3/B-/B-, a one notch downgrade will take Pakistan to Caa1/CCC+, a rating level considered extremely vulnerable to default. That will make a bad situation worse.

*the difference between a USD denominated bond’s yield and comparable maturity US treasuries.

The above views are the personal opinions and assessments of the author. They should not be construed as investment advice. He can be reached on [email protected]

The most recent placements, six since April 2021, have totalled $5bn including bonds from the government-owned Water and Power Development Authority. This is the most frequent and largest amount raised via Eurobonds over any 12 month period by Pakistan. And this has had an impact on the bonds post issuance performance.