If there was ever a time to go to the landa, it is this year. Let us explain.

You see, most if not all of the clothes you find in flea-markets and thrift stores are hand-me-downs that have been given away in charity by people in countries like the United States, England, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. And because the charities get these clothes for free, they sell them in bulk per-Kg at practically nothing. The clothes then make their way to third-world countries like Pakistan where they are sorted and sent to the market.

For example, the Catholic Church might collect a brand-new Ralph Lauren shirt as part of a clothes drive in Boston. Donors often think that the clothes will be shipped off to the third world to be distributed freely among people that need them. This is a common misconception.

In reality, charitable organisations end up collecting so many articles of clothing that it would be difficult and expensive to package and deliver them to the needy. Since charitable organisations get these clothes for free, what they do instead is find a retailer willing to buy the clothes from them at a set price per Kg and use the money from this to engage in other charitable activities.

Now, that brand-new Ralph Lauren shirt would have cost $110 at retail price in the US. But as part of a 50Kg bundle being bought by a used-clothes merchant at a rate of say $2 per KG, that shirt ends up costing literal cents. These bundles of clothes are then sorted, packaged, and shipped to third-world countries where they are sold at low rates. A shirt in the US that would have cost $110 in the US (Rs 31,000) will be available at a flea-market in Lahore for as low as Rs 1000-1500 ($4-5).

It is a classic example of the economic concept of arbitrage, in which you buy the same product in one market at a lower price and sell it in another market at a significantly higher price. But then why is this year going to be better for the landa? Normally, the thrifted clothes that arrive in Pakistan are so cheap that merchants from other countries such as Turkey, Afghanistan, and India buy these clothes from Pakistan at a slightly marked up price.

That’s right. Pakistan imports these landa-bound clothes at such cheap rates that they then sift through the clothes, find the most high-quality product in the best condition, and export them in a strange case of double-arbitrage. Except this year things are a little different. Because of the continuing forex crisis in the country, the government has set a 300% import duty on these clothes.

As a result, the clothes will become too expensive to export, meaning the buyers from countries like Iran and Afghanistan have largely said they won’t be buying the clothes. This means two things: the first is that the clothes at the landa this year are bound to get more expensive and add to the inflationary trends in the country. The second is that because foreign merchants will not be picking up these clothes, the clothes will be of a better quality and be more in quantity. So how will this play out? To start, we need to get into the finer details of landa economics.

The landa arbitrage market

It is a pretty linear system. Charities, churches, and community centres collect clothes that people give away in foreign countries. The clothes are mostly hand-me-downs. As we mentioned earlier, charitable organisations do not have the time or the resources to sort and deliver these clothes to people that need them. Instead, they pack them up into huge bundles that weigh up to 60Kgs and sell them.

Who buys these bundles? There are retailers that have made a business out of hand-me-down clothing. In the UK, for example, there are enterprising Pakistani expats that store the clothes in warehouses. The first thing they do is open these bundles up and sort the clothes by categories. Pants on one end, shirts on the other, shoes in a different corner and so on and so forth. After this, each pile is sorted for quality, and by the end you have different kinds of items categorised by quality, age, and by brand. Out of this, the best quality products are sent off to thrift stores within the country. So if the warehouse is in Bradford, England — the best clothes will go to thrift stores in Bradford where they will fetch the best price.

The rest of the clothes are then exported. They are fumigated (this is where the infamous ‘landa smell’ comes from), once again bundled up (this time pre-sorted) and then shipped off to third-world countries. The market for this is massive, and Pakistan is one of the major importers of these clothes. According to a 2015 article in The Guardian, most donated clothes are exported overseas. A massive 351m kilograms of clothes (equivalent to 2.9bn T-shirts) are traded annually from Britain alone. The top five destinations are Poland, Ghana, Ukraine, Benin, and yes, Pakistan. Low-income families then shop at these markets, where winter clothes are in high-demand.

The report estimated that globally the wholesale used clothing trade is valued at more than £2.8 billion. It is a textbook example of arbitrage. Donated clothes are sold dirt cheap in developed countries, but since they are not readily available to low-income families in the third world, their value is higher in that market. Arbitrage is essentially a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets. In fact, an example of arbitrage often cited in textbooks is that of vintage clothing, and how a given set of old clothes might cost $50 at a thrift store or an auction, but at a vintage boutique or online, fashion conscious customers might pay $500 for the same clothes.

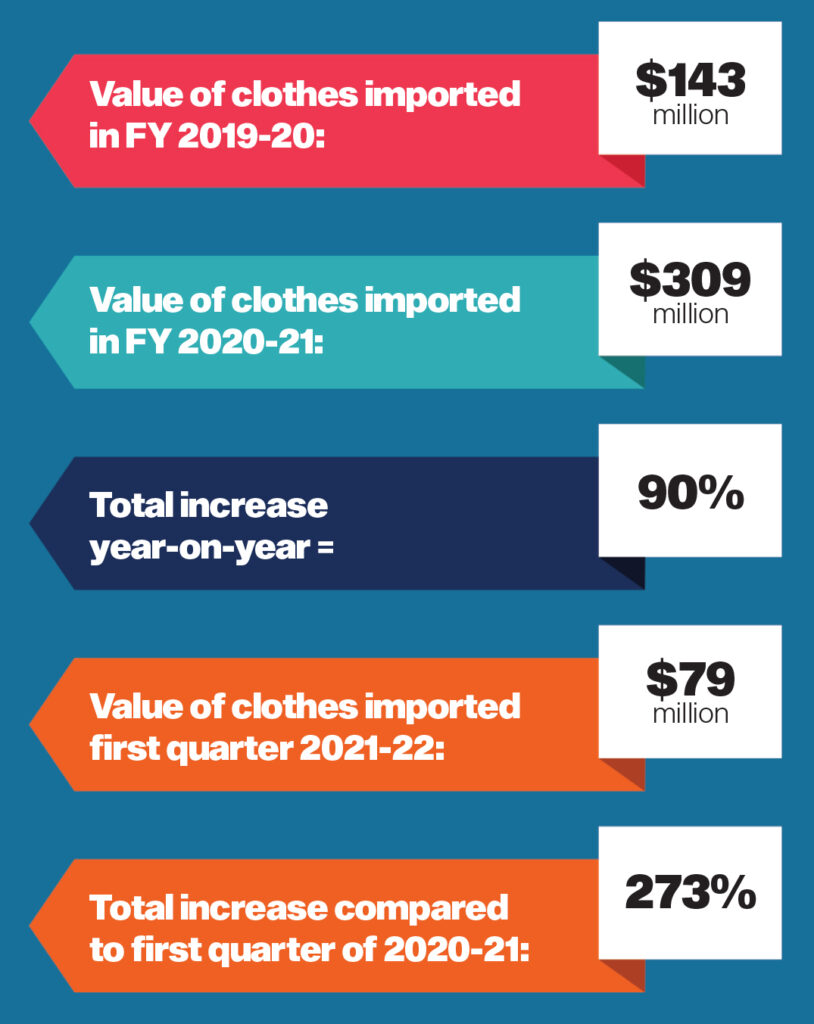

Pakistan plays a significant role in this arbitrage, and in the past few years the demand for these clothes has only increased. According to data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), during the last fiscal year (FY 2020-21), the import of used clothing increased by 90 per cent to $309.56 million and it weighed 732,623 metric tons. The year before that, there was an increase of 83.43 percent in terms of price. Pakistan imported 186,299 metric tons of pre-used garments during the first two months of the FY 2021-22 (July-August), which makes up for an increase of 283 per cent over the same period of last year, which translates to a spending of $79 million.

How it works

Now, this is where things get really interesting. You see, the shop-owners at the Landa are not the ones directly importing these clothes. Bulk importers get the clothes in massive quantities worth millions of dollars and bring them to Pakistan in containers. Land owners then buy these containers without seeing the contents inside — which means the quality of clothes you are getting depends on the luck of the draw.

“Be it an importer of pre-used clothes, a wholesaler, a shopkeeper or a wheelbarrow, no one has ever lost in this business. The main reason for this is that the price fix is only for the imported container and not for the pre-used clothes coming out of it. We take the pre-used clothes from the importer or wholesaler where the clothes are delivered in bundles and the price of the bundle depends on its weight, grading and type,” says Shams Khan. A native of Peshawar, he has been selling clothes to Lahore’s landa bazar for decades now.

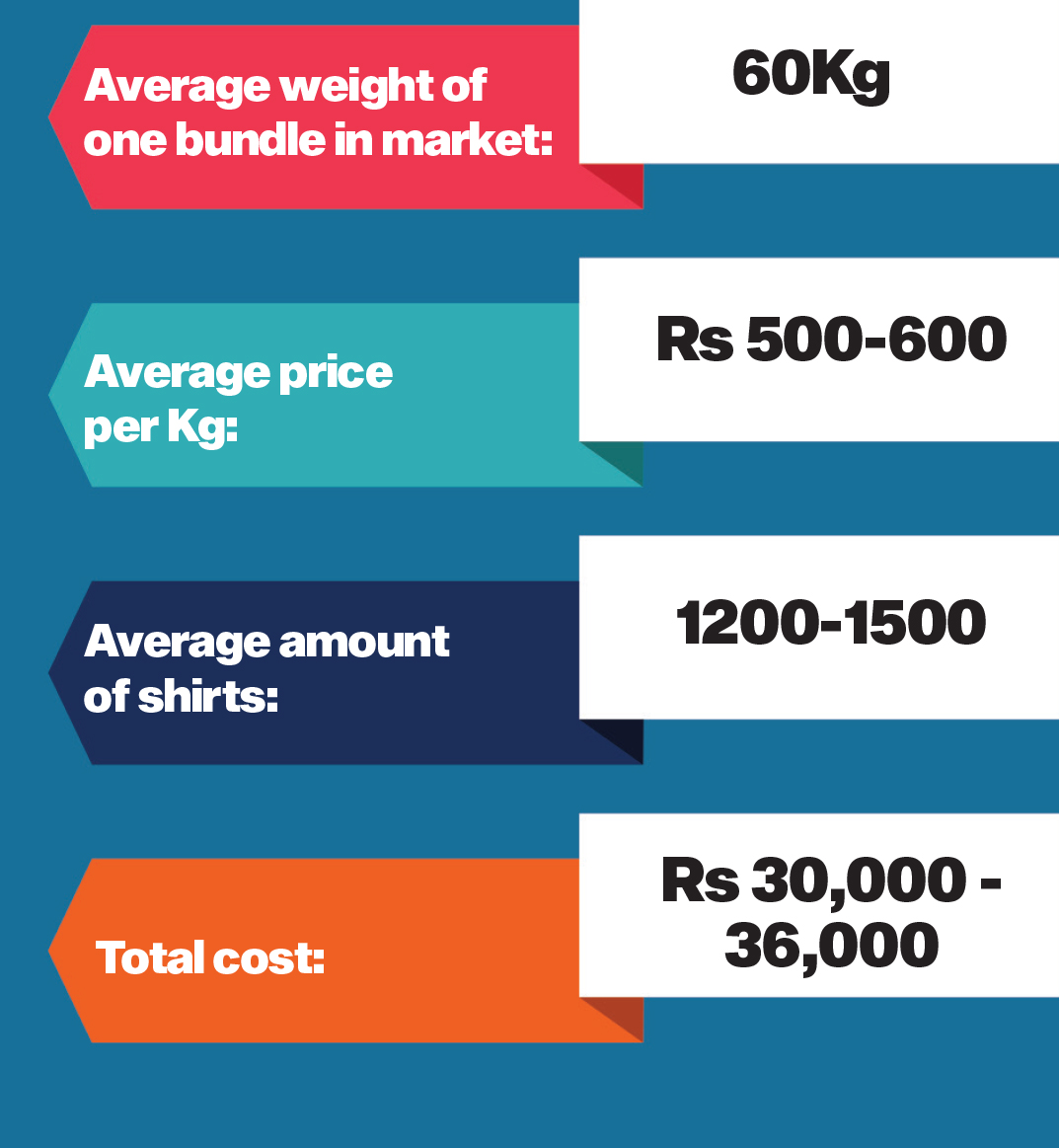

According to him, there is no way anyone can make a loss in this business because of how ridiculously cheap the second-hand clothes are. One needs to understand that these clothes are extremely undesirable in their home markets, and the traders that buy them there buy them from charities that want the masses of clothes off their hands and quickly, which means they settle for very cheap rates. “Very simply speaking, if I buy a bundle that has been tagged as B category, and the bundle weighs around 60 kilograms, then I have to pay RS 500 to RS 600 per kilogram for it. So this 60Kg bundle ends up costing me around Rs 36,000. Now, we take the example of t-shirts, then it takes around 18-20 t-shirts to make one kilogram. This means for Rs 36,000 I have hypothetically bought 1200-1800 t-shirts if that is all there was in the bundle,” he explains.

“When we sort the bundle approximately 500 to 600 shirts come out that look brand new and these shirts are of famous brands and easily sell for between Rs 300 to 500. Now if I sell 500 shirts myself for Rs 300, it becomes RS 150,000 and think for yourself, I bought this bundle for 36,000, so I have more than tripled my initial investment. The other aspect is that I do not sell these 500 shirts myself but I sell them to five different shopkeepers at the rate of Rs 150 per shirt. Even then I earn Rs 75,000 and make a profit. The rest of the 1000 shirts that were not as high quality I can sell to smaller shop owners or roadside merchants. At the rate of Rs 50 per shirt, I can earn another Rs 50,000. There is no losing here.”

There is no loss here because, as we have gone to painful lengths to explain, there is no loss in arbitrage. The shirts are so dirt cheap in the countries they come from because they are considered worthless. Even if they were given a price, no one would buy them since brand new clothes are not that expensive either. They are sold cheap according to weight, and since people here don’t have access to cheap new clothes, they buy the second-hand products for significantly less than what they would have to pay for new clothes.

This year’s quandary — the import duty

The issue this year is the increased import duty of 300% that has importers up in arms. This increase is expected to increase the prices of used items, but due to the decrease in exports, market experts are also indicating that a large number of these clothes will enter the market. That means even though prices will go up, the quality of the clothes will be better and people could find practically new clothes at second-hand rates.

“It is a 300 percent tax. Call it valuation duty or whatever but it is essentially quadrupling the price of the warm clothes that the poorest segments of society buy and wear, says Usman Farooqui, General Secretary of Pakistan Second Hand Merchants Association. According to him, a container of Landa clothes that used to cost RS 700,000 last year now costs Rs 2.7 million.

“The poor importer, who was already worried about the rising value of the dollar, is now further burdened by taxes. Landa is already subject to several taxes, including sales tax, in addition to valuation duty, due to which Landa’s clothes are becoming more expensive,” he lamented.

“The previous government had increased the regulatory duty by 10%, and now the value has been increased from 36 cents to 1 dollar and with this increase, second hand clothing has become expensive, up to 300%, and has become beyond the reach of the poor. Due to this increase, hundreds of our containers remain at the ports and we continue to pay fines on the basis of detention. Imports of used clothes in Pakistan are worth around $100 million.

{Note from the editorial team: The $100 million is an estimation given by Mr Faroouqi. The latest figures available from the PBS are from 2021 and show an import value of $80 million. Figures for this year are not available yet.}

On the other hand, Faisal Memon, manager of a company in Karachi, which has been in the business of importing and exporting Landa clothes for the past two decades, told Profit that due to unavailability of full stock with his company in winter he could not export as much as he was doing in the past.

“The increase in taxes and duties has not only affected the prices but also the export of these used garments from here. When the government increased the taxes, many importers did not clear their containers from the port because they thought that the government might withdraw or reduce the tax. Due to increase in taxes, the trend of importing containers of used clothes and toys is also decreasing,” he says.

“We have customers from Iran, Afghanistan, South Africa and Turkey. When the container is bought from the market, it is graded and the supply is sent to each customer in their country according to their demand. The market situation this time was that most of the foreign customers were willing to pay the asking price for used clothes and shoes, but due to non-availability of goods, many exporters could not meet their demand.”

Mian Fayyaz, a trader of Lahore Landa Bazaar, informed Profit that due to high duty and taxes on used clothes, the big merchants of Karachi are not able to supply these clothes to other cities at the moment due to which the business of the shopkeepers is also going down.

“Before the summer season started, I visited the importers in Karachi twice, from whom I have been buying for the last ten years, but they could not supply me what I wanted. These merchants do have used clothes but they are mostly old and of poor quality. These types of clothes are usually sold on carts in markets but since I am a shopkeeper and I have customers who are into used clothes and they demand from me a quality that is brand new.”

“In our market in Lahore, people are either selling the stock of the previous season or the clothes they are ordering from Karachi are of the previous season. In this situation, these used clothes will become very expensive and our business will slow down,” Mian added.

Enter the Insta thrift stores

Ultimately, will anyone benefit from this? On the one hand, better clothes will hit the landa market this year. On the other hand, prices will go up. Importers, shopkeepers, and shoppers will all largely be unhappy. But there is one segment of the market that could reap the benefits if they play their cards right — Instagram thrift stores.

In the past few years, things in the landa have started to change. People from relatively affluent backgrounds, mostly women, have started visiting the landa and sifting through the second-hand but branded clothes and buying them in bulk. They then sell them online through Instagram, marketing themselves as sustainable fashion brands dealing in ‘pre-loved’ clothes.

A big market is students. College going students need clothes, and a lot of the time they do not have the money to buy designer clothes that are a status symbol in elite universities. So for those students on a budget that want to keep up with their richer peers, the landa has been a saviour for decades. While the clothes might not be in the best condition, they are branded, comfortable and stylish.

Middle and upper-middle class sensibilities keep people away from the landa, because the market is dingy and there is a complex about buying used clothes. However, young people are able to traverse shabby markets and have less of an ego when they are on a budget. International brands are readily available at the landa and with some washing and sprucing up, entire wardrobes can be made for dirt cheap. These clothes are often even noticed by their high-rolling peers, who recognise the brands as not easily available in Pakistan. This was all there was to it, until of course, Instagram came about.

The trajectory has actually been quite ingenious, and the way some of these pages operate is truly enterprising. “I used to get almost all of my clothes from the landa since I started studying in Karachi,” says one student from IBA that runs a thrift store on the side when she isn’t busy with her studies. “I’ve always gotten compliments from friends and strangers alike for my outfits. It isn’t just as simple as going to the flea-market, you really have to have an eye for the right stuff and that means knowing about fashion.”

It is actually very enterprising work to be going to the landa and then selling clothes from there through Instagram. People do not like going to flea-markets, so these people with an eye for fashion and an understanding of landa dynamics go to the market for them. Many of these women then buy clothes and shoes in bulk, bring them back home, clean them or fix them if they need fixing, and after that photograph them aesthetically. Some of them even model the clothes themselves or get their friends to model them for them. “There is barely any additional cost. There is the Careem fare that I incur going to and from the landa, and then sometimes I wash the clothes again, and then I put them on, set my camera on timer-mode and model them myself too. I upload the pictures and start getting DMs, my customers then bank-transfer me the payment and they pay for shipping too,” says the online thrift store owner we spoke to.

They brand their products as ‘pre-loved’ or ‘rescued’ and supporting sustainable fashion, which they claim is environmentally friendly. All of this coupled with well-done photography means that middle and upper-middle class people that see these pages are more than happy to buy from them, especially since they are so cheap.

And all of this is why this year could be big for the Insta thrift stores. For starters, they have a very good understanding of what products are high value and what brands sell better and go for better rates. On top of this, they have the added advantage of a clientele that buys sitting from home and not by going to dingy flea markets. As a result, people will be willing to pay more — especially for branded products.

A shirt that came to the landa at Rs 200 last year and was sold at Rs 500 was already selling at Rs 1100 on these online thrift stores within minutes of being posted. This year, people are more likely to buy a branded Rs 2000 shirt from an online thrift store rather than a Rs 800 shirt from the actual landa market. That is where the opportunity lies. And as soon as more containers start to be released and the clothes hit the market, it will be an opportunity worth cashing in on.

There is further discussion on this article on Twitter. Be a part of it:

There is no better time to go to the landa than this year. Prices will be low and products plentiful. But why? The story behind that has to do with the unique economy of Pakistan’s landa bazars that rely entirely on the economic concept of arbitrage {THREAD} pic.twitter.com/GAiTmVRvlJ

— Profit (@Profitpk) April 27, 2023

Developing countries like Rwanda are banning used clothes imports, be good if this issue had been discussed in the PK context.

Rwanda banned second hand clothes imports in 2018. The ban was aimed at boosting its textile industry.

As an individual who is running a second hand company in KEPZ in Karachi, I would like to point that there are some inconsistencies in your article.

For example, you suggest that “it takes around 18-20 t-shirts to make one kilogram”, this is quite inaccurate. 1 kg of T-shirts only consists of around 4-6 T-shirts at the maximum. This tiny error has made the majority of your calculation incorrect. Additionally, I am unsure as to how you have come to conclude that one small bale is around 60kg. Roughly, small bales in the local market are around 40-45kg.

Regarding the main argument of the essay, which supports the notion that due to the higher prices, Iran and Afghanistan, border countries, would want to reject the better quality of goods provided by Pakistan. This quite inaccurate. This is because the goods that are leaving Pakistan are not intended for this market anyways due to the dynamic. And even if they were suited to the local market demand, what makes you think that local buyers have the buying power to out compete bordering countries.

To stick with your argument, if you think that Iran / Afghanistan won’t purchase the goods due to the imposed duties and costs on the prices, then what makes you think that Pakistani locals can? Further, the Iranians pay for these goods in USD. Hence, the Pakistani devaluation against PKR actually makes it cheaper for them to purchase Pakistani goods.

Other than these points, an insightful article. I am glad to see that people are talking more about this niche market. It was also interesting to see how you have explained the concept of Landa under the term of ‘arbitrage’.

ello good afternoon, I am Fran, I am talking to you from Madrid, we are interested in exporting vintage clothes from your warehouse to Spain, we wanted to verify the material you have, since we are looking for the highest possible quality, our idea is to place an initial order of about 1,000-2000kg, to later bring a much larger order. Currently what our customers are looking for are top brands, and good quality, all grade A