Every year on the 2nd of May like clockwork, the city pages of almost all major newspapers in Pakistan carry the picture of a labourer. It doesn’t matter who that labourer is, what their name is, or what they are doing. It could be a man carrying bricks in the sweltering sun or a woman picking cotton in a rural area but the point is always the same — the irony of the labour day holiday.

While most people use the labour day public holiday for a long weekend, most daily wage labourers continue to toil. This, of course, is not the point. The state of labour rights in Pakistan is abysmal and it is not just to do with wage labourers. Sub-contracting, no protections, and a complete absence of unions make workers a deeply vulnerable class of people in the country.

And the most at-risk group of workers in Pakistan are those working either on daily ‘dihari’ or those working on minimum wage. The problem with Pakistan’s minimum wage has many faces. Not only is the wage understated and miscalculated, but even if it were an honest representation of subsistence in the current economy, the enforcement and awareness regarding minimum wage has lightyears worth of work to do, if it is to reach global standards.

The economics of the minimum wage line

The term minimum wage is self-explanatory. Legally, minimum wage is the minimum amount an employer is allowed to pay to a worker for their labour.

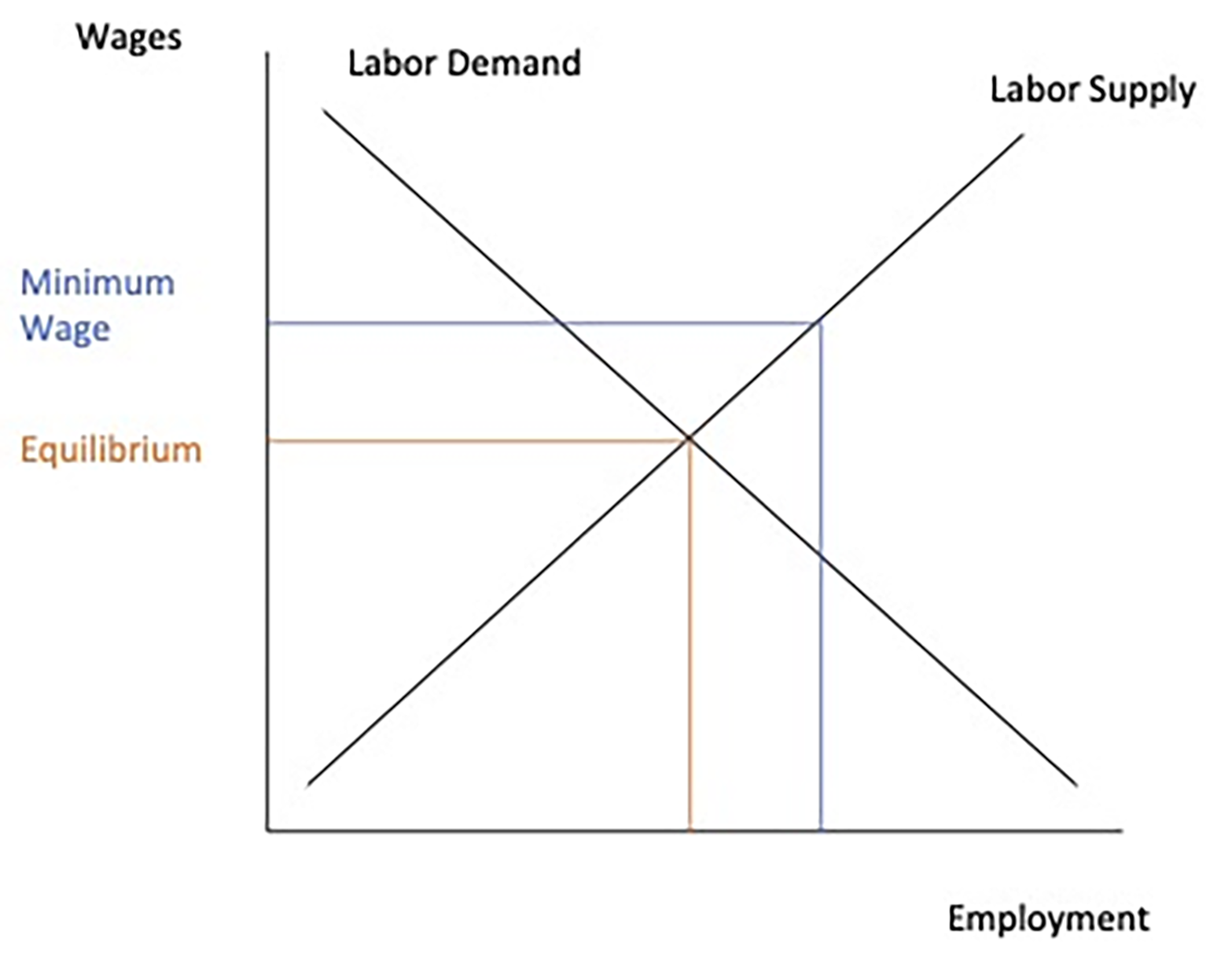

In economic theory, it is taken as a level wherein anyone who earns minimum wage is living a livelihood, good enough to take care of their basic human necessities. In fact that is the entire reason minimum wage exists. In a market economy of supply and demand, labour supply will mostly exceed labour demand. Meaning that a country where the majority is not educated, or not skilled will have an abundance of people who would want to take up menial jobs. This would lead to a scarcity in jobs and more and more people will be willing to work for less.

Unchecked this will go on to a point where people will start working for peanuts, and the quality of life will become abysmal. Why will they do it? Because something is still better than nothing. So to avoid such a circumstance, minimum wage is set, as a baseline. So that despite any saturation or competition. The quality of life of the citizens of a state is not compromised upon.

The process to figure out the minimum wage, however, is contentious. In general, governments consider a range of factors when setting the minimum wage line, including the cost of living in an area, the level of inflation, and the overall health of the economy. They consult with experts and stakeholders, such as labour unions and business groups, to gather input and feedback on the proposed minimum wage line. Once that is settled minimum wages are set.

Where does Pakistan go wrong?

So apparently, apart from the definition, the calculation, the maths, the enforcement of minimum wage and the very definition of quality of life, the status quo is pretty set in stone.

In Pakistan, the minimum wage laws are set by the federal government and are enforced by the provincial governments. The minimum wage rate varies by industry and sector and is periodically revised based on inflation and other economic factors.

Section 4 of Minimum Wage Ordinance, 1961 allows Minimum Wage Boards, for each province, to recommend minimum wage rates for adult unskilled workers and juvenile workers employed in industrial undertakings.

Let’s now look at the problems with the minimum wage level.

The monthly nature

Pakistan uses a monthly minimum wage system. As compared to most of the developed world, Pakistan does not have hourly wages. Mostly this wage is taken up to a 26 day month.

As per the time of this scribe, Punjab has a minimum wage of 32,000 while Sindh Balochistan, KPK and federal all have a minimum wage rate of Rs. 25,000. Even a bill to increase the minimum wage in Sindh assembly has been tabled, no results have been actualized.

There is not a lot that is wrong with the monthly wage rate. Not so much as there is wrong with using it as the umbrella wage rate.

Merely using a monthly rate may not account for fluctuations in work hours, which can vary from week to week or month to month. This means that some workers may earn less than the minimum wage on a per-hour basis during slow periods, which can make it difficult to make ends meet. But this is the least of the problems.

Another big problem is that a monthly minimum wage may not adequately account for differences in living expenses across different regions or cities. For example, the cost of living in Karachi will be much higher than in a rural part of Jamshoro, but the monthly minimum wage is the same for both locations. This is of course a principle problem with monthly wage rates. In reality what is being paid to a rural worker in Pakistan, is something you would not wish upon your worst enemies, thanks to centuries of feudalism and bonded labour.

It is important to note that the Minimum Wages for Unskilled Workers Ordinance 1969, wages have both the fixed and variable components. The variable components include dearness allowance, house rent, conveyance allowance, cost of living allowance and special allowance. However, such “unimportant” details are often overlooked whenever the minimum wage levels get revised. Any rates or allowances, sans the monthly level, which were ever applied, are no more applicable.

Now that the principle flaws have been talked about we look at the substance of the already defined rate.

The understatement problem

If you asked any Pakistani 2 years ago, they would have told you that 25,000 is not enough money to lead a respectable lifestyle. In an average household of 6 people, 25,000 barely covered the food and shelter costs. Things like electricity, gas had to be saved up and things like education and health were put on the back burner. But 2 years ago, the minimum wage was not even 25,000.

Let’s now come to the present day. Inflation has soared high as year on year inflation has breached 35%. This essentially means that if your income was 25,000 a year ago, it needs to be well over 33,000 right now for you to wield a similar level of purchasing power. The minimum wages were raised 10 months ago and since then Pakistan has seen a cumulative total of 30% more in inflation.

But even that is not the complete picture. With core inflation lower than the headline inflation, energy and food prices have gone up with a significantly higher multiple than other things. Infact, the food inflation alone in April stands at more than 48%. This means that a household’s bottomline is more difficult to protect in the current inflationary environment.

Exec. Director, Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) recently projected in an interview that each worker should be given a minimum of Rs 50,000 a month to afford essential things and services such as food, drinking water, education, and healthcare services.

Open social media and you will see that various people have come up with various numbers, when it comes to estimating what the minimum income should be. However, none is even close to the 25,000 mark that is prevalent right now.

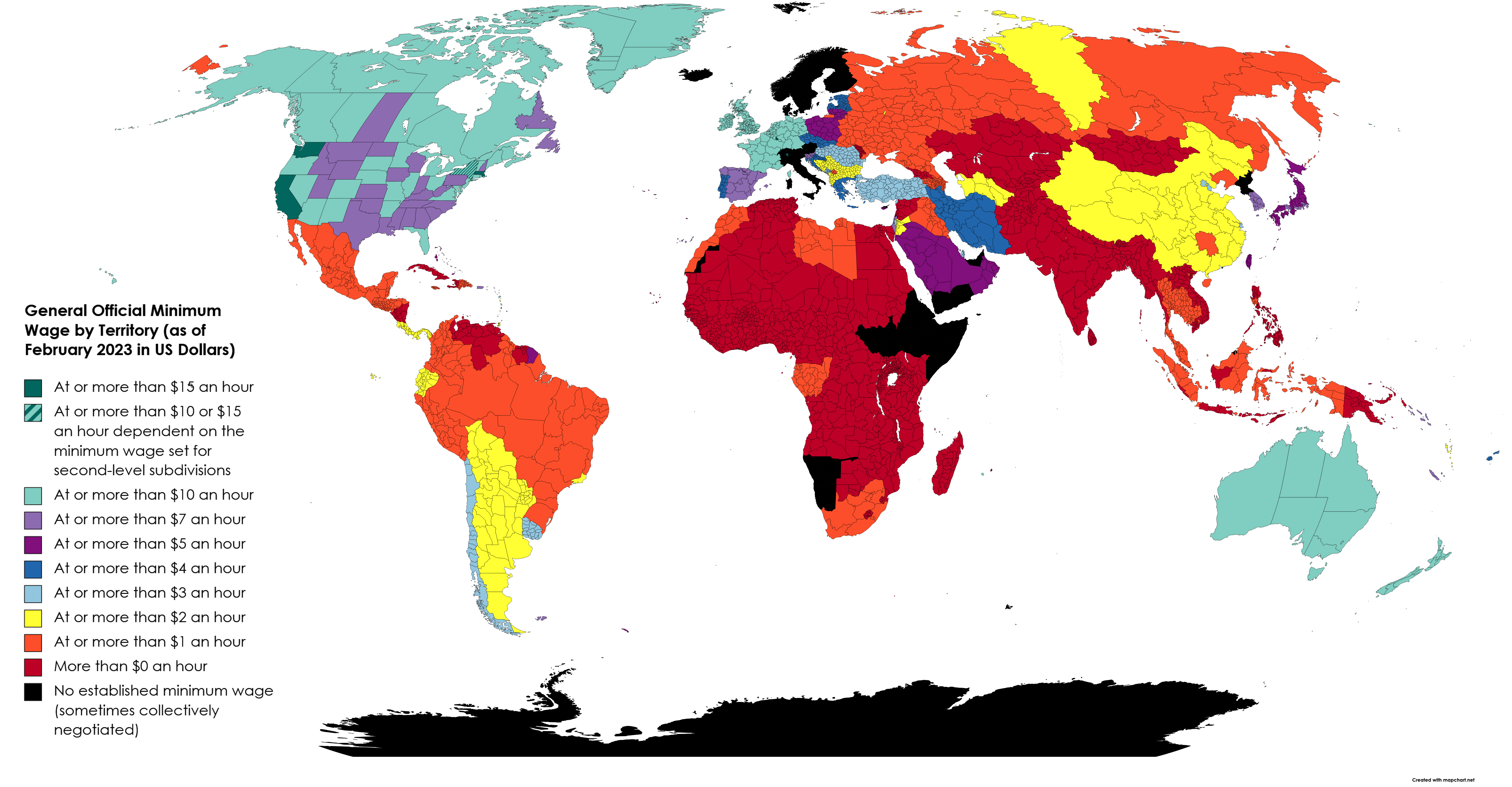

As per the world bank, $2 per day is the minimum a household requires to meet its necessities. However, it was the world bank that reported about 18 months ago how 83% of Pakistanis do not have access to this amount on a daily basis. Since then the dollar rate has almost doubled. This is to clarify that the levels at which minimum wage has been set has never been enough. It is not just about the current inflation. It has always left room for labour exploitation.

Now let’s for a second assume that the aforementioned problems with minimum wage do not exist. Let us hypothesise a world in which minimum wage levels were defined precisely and were comparable with the dollar equivalent of other global minimum wages. It would still be a problem. Why? Because of the enforcement of these laws.

The enforcement problem

According to the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER), an estimated 80% of unskilled workers are not receiving the minimum wage of Rs25,000 per month, which was awarded a few months ago. And this is where the crux of the problem lies.

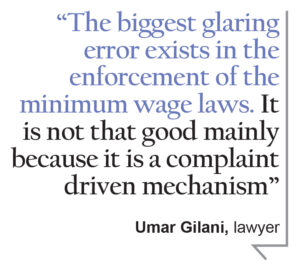

Talking to Profit; lawyer and labour rights activist Umar Gillani stated how the enforcement is all over the place. “The biggest glaring error exists in the enforcement of the minimum wage laws. It is not that good mainly because it is a complaint driven mechanism.”

He informed that in his experience, most of the people who were being underpaid did not possess the means to turn on their employer. And that makes sense, a person who knows he will be replaced the moment he steps out of line is highly unlikely to go against his employer.

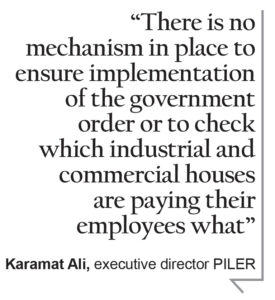

Talking to a media outlet, the Executive Director PILER, Karamat Ali said that, “There is no mechanism in place to ensure implementation of the government order or to check which industrial and commercial houses are paying their employees what.”

Factor in the lack of public education and basic civics, the person might altogether be unfamiliar with the very existence of minimum wage laws. Of course it is not to say that those who do know about their rights have a secure working environment. And can willingly seek protection from labour exploitation.

Talking to Profit, on the subject of anonymity, a utensil factory owner from Rawalpindi, stated that it is not in their best interest to hire adult men. “These men have families to take care of. Not only are they not willing to work the proper(after) hours, they also expect a salary of more than 20,000. 20,000 is what we give our experienced workers”. The factory owner also made a compelling case for hiring younger boys instead. Adult boys who were not expected to contribute significantly at home.

The awareness problem

They say that ignorance is bliss, but not in this case. In fact one of the very reasons as to why employers are able to exploit labour in Pakistan is because they are unaware.

Unionisation is actively discouraged and any work that is done to raise awareness amongst the masses. According to Mr. Karamat Ali, Pakistan needs to carry out a rigorous awareness campaign across various media much like the UK government did in the year 1990.

Awareness comes hand in hand with another thing and that is education. A lot of the labour would not be unskilled to begin with if it was for education. But that is just the tip of the iceberg.

Many workers, for instance, are unable to take legal action because their contracts are not renewed once they expire, and they lack proof of employment. Without the proof of employment it becomes easy to lay them off if they want a better wage.

Of course awareness can only do so much. The power that the rich wield in a country with polarity in power structures makes it impossible for the poor to take up arms against the rich. It is perhaps this very reason that stops this topic from being on the agenda of assemblies and on the manifestos of political parties.

Conclusion

Due to the systemic problems prevalent. The situation is many times worse than can be seen on the infographic. Pakistan may be above the 0$ mark but the countries below us are only those that do not even have a requisite minimum wage.

Minimum wage is important to talk about because It highlights the urgent need for action to address poverty and inequality in Pakistan, and to ensure that workers are paid a fair wage for their labour. It is a reminder that behind the statistics and numbers are real people with real struggles, hopes, and dreams. Something that should take a far greater precedence over power politics.

And the minimum wage is not just about money. It’s also about dignity and respect. When workers are paid a fair wage, they feel valued and appreciated for their hard work. They can provide for their families and contribute to their communities. And when everyone is paid a fair wage, it creates a more just and equitable society for all. When we talk about minimum wage, let us not forget the human cost of poverty and the urgent need to address it. Let us not turn a blind eye to the suffering of those who are trapped in its grip, but instead, let us work together to create a brighter future for all Pakistanis.

Super site! I am Loving it!! Will return once more, Im taking your food likewise, Thanks.

there are too many grammatical errors in this article