The economy has never been this bad; the cost of borrowing money has never been this prohibitive; and businesses have never laid off workers and closed down plants at this scale before.

And yet, one of Pakistan’s largest commercial banks, United Bank Limited (UBL), was able to make an astounding 28% additional loans to businesses towards the end of 2022. This was only a few months ago, and at that time UBL was not the only bank lending money like there was no tomorrow. In fact, total outstanding loans by commercial banks increased rapidly by a massive Rs 820 billion in December 2022 alone. This is the highest monthly increase ever recorded in the combined loan portfolio of the Pakistani banking industry. And that is not just in absolute, but also in percentage terms.

This raises the question: who were these businesses that were borrowing so much money, and that too in such turbulent times? What makes all of this even more suspicious is that the specific banks leading this sudden spurt in lending have long been famous for being averse to the concept of lending to the private sector.

Something is clearly amiss here.

Could it be that these banks may have cooked their books by making bogus loans? And if so, how did the most regulated sector in the country get away with it? And perhaps even more importantly, what could have prompted the banks to undertake such a risky mission in the first place?

To answer these questions and to understand what really happened, we need to go back to December 2021 to a scene in Dunya TV’s studio where anchorperson Kamran Khan was interviewing the then finance minister, Shaukat Tarin. But first, some basic background of how banks work.

Advances vs Investments (feel free to skip if you know the difference)

The first thing you might have heard about how banks run their business is that they are essentially intermediaries. They get money from people who have excess money (depositors) and then channel it to those who need it (borrowers). Banks make a profit by charging a spread between the interest rates they pay on their deposits and the interest rates they charge on their loans. For the latter, banks have two options.

Firstly, they can lend to the private sector, which includes businesses, to finance new machinery, raw materials etc., and individual consumers, for automobile financing, credit cards etc.. This lending to the private sector is called ‘advances’ in banking parlance.

The second option for the banks is to lend to the government. We know that each year, without fail, the Government of Pakistan spends more than it earns, and the shortfall arising out of this, it finances through borrowing. The government does most of this borrowing from Pakistani commercial banks, by selling government bonds to them. These bonds are essentially pieces of paper (or digital records) stating the amount borrowed by the government, the interest rate the government will pay to the bondholder, and the date at which the borrowed amount has to be repaid to the bank. This lending to the Government of Pakistan is what in banking jargon is called ‘investments’.

All banks use a mix of both advances and investments to deploy their funds profitably. The problem is that some of Pakistan’s largest banks (remember UBL in the intro?) are significantly more inclined to make investments (lend to the government), than to make advances (lend to the private sector).

This is a problem because commercial bank’s primary role in the economy is to channelise funds to private businesses. And this is where Shaukat Tarin comes in.

Additional tax and the Koonda threat

In April 2021, Shaukat Tarin once again donned the mantle of finance minister. Up until his appointment, nobody was really concerned about large commercial banks lending more to the government than the private sector. Well at least, nobody important.

That Tarin felt very strongly about this was well known amongst the bankers. In fact, Tarin, during his stint at Citibank, had practically invented consumer finance in the country. So the banks might just have expected what came next.

In Sep 2021, Tarin decided to penalise banks that were not lending enough to the private sector. He did this by imposing an additional tax on banks that by the end of the year would not have made their total outstanding advances (read loans to the private sector) at least equal to 50% of their deposits figure. More specifically the metric they used to levy this additional tax was the advance-to-deposit ratio (ADR) which measures lending as a portion of deposits.

The idea was simple, Covid-19 was subsiding, inflation was still low and Tarin thought it was time to kickstart the economy. At worst, the government would end up earning a higher tax revenue from banks, and at best banks would start lending more and through that Tarin could deliver growth.

However, while Tarin may have been approaching this from the vantage point of a banker, he was still the finance minister of Pakistan. His ministry still had to actively borrow from the banks to finance the government’s perpetual deficit. In November and December of the same year, the finance ministry asked the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) to conduct an auction of new government bonds and try to sell these to the banks at the lowest possible interest rate, as it normally does.

All of the major banks submitted their bids for the government bonds but it very quickly became apparent that they were all offering their money at an interest rate that was much higher than usual.

The government and the SBP were clearly upset. They accused the banking industry of banding together and acting greedy. The banks said that they were expecting inflation to go up, and thus interest rates to follow suit as well. It only made sense for them to lend to the government at higher than prevailing interest rates they retorted. The banks argued that this was not greed but good judgement as otherwise they could get stuck with bonds which offer lower interest rates. This was the official statement. However, privately in conversations with Profit bankers argued that it was logical that banks that had a low ADR would want to be cover the higher tax rate that was recently applied on them, by demanding extra return from the government in its bond auctions.

This is when the term Koonda went viral. In Dec 2021, during a live program with Dunya TV’s anchor Kamran Khan, Tarin threatened banks regarding their high bids in the government bond auctions, by saying that if banks do not start behaving he will very easily deploy tools that will ruin the banks (in ka koonda ho jaye ga).

Despite the threat of severe action, banks nonchalantly continued as normal, even pushing their bids further up. To be fair, expectations of a higher future inflation and in turn higher interest rates had set in by this time. But that still does not explain as to what gave banks the confidence to look both the government and the SBP in the eye.

Banks smell blood

The government previously had the option to borrow either from the banks or borrow directly from the SBP. The SBP could create new money to buy government bonds at low interest rates whenever it felt that banks were not offering favourable interest rates on government bond auctions. This creation of new money would obviously have been inflationary, but it was an option nevertheless, and one that was used quite often. But as per an IMF condition, under the amendment made in the SBP law, the government was recently barred from borrowing from the central bank. With the government unable to borrow from its own banker, they had to turn to the commercial banks to keep the water running in the taps.

The commercial banks had caught on. They could smell the blood and felt they had the upper hand as they had essentially become the only lenders to the government.

Seeing that banks, despite the threat, were adamant on demanding higher than usual interest rates from the government, the SBP was forced into a work around. It started creating new money, but this time it was lending at low rates to the banks, which in turn would invest this cheap money in the government bonds after keeping a small spread. This was similar to when before the amendment in the SBP law, SBP would invest directly in government bonds, except this time banks were making a small spread in the process, that too without using any of their own funds.

The banks were obviously very happy as under the new arrangement they could continue to make profitable investments in government bonds and that too without having to worry about the negative impact of making too much of an investment on the bank’s ADR. You see ADR is advances divided by deposits. Now banks were making most of their investments using the money they borrowed from SBP, hence it was no more an either or choice for the banks between making advances or making investments. They could now continue to make investments, using SBP money, and make loans from the deposits if they wished to.

This was, in essence, a four month long chess match. The government had made an aggressive opening play and the banks had responded by sticking to their guns and taking advantage of the fundamental weaknesses in the federal government.

Let’s recap. Banks were comfortable lending to the government and earning interest income rather than lending to the private sector, the former being more secure and easily executed. Tarin, the finance minister at the time wasn’t having any of it and in a bid to force banks to lend more rather than just buy government-backed securities, placed an additional tax on any bank with an ADR lower than 50%. Banks doubled down, demanding an even higher return on government securities to cover the cost of the new tax. Tarin’s finance ministry, as a result, might have made more money in taxes from these banks, but it would have probably ended up paying the same money or more back to the banks in the form of additional interest rates on government bonds. To bring the government’s cost of borrowing down, SBP starts lending cheap money to the banks, which they can lend further to the government. But by now the relationship between the government/SBP and the banks had clearly become sour.

Miftah doubles down

In April 2022 Tarin and his boss, Prime minister Imran Khan were removed from office through a vote of no confidence, and Miftah Ismail became the new finance minister of Pakistan. Miftah and the new governor at SBP, who was in Tarin’s tenure the deputy governor at SBP, also seemed convinced that the banks were being too greedy, making more than they should, and must be punished.

Miftah further increased the ADR tax. Banks by now had had enough of trying to fight this tax by increasing the interest rates they demanded on government bonds, as there were too many dressing down sessions at the SBP, and other inquiries that they had to go through.

Also, not every bank had a low ADR issue and therefore no additional tax cost to cover by making higher interest rate bids (demand) in auctions. So the banks with above 50% ADR would have most likely outbid the banks with low ADRs had the latter asked for higher interest rates.

Simultaneously, the SBP was continuously injecting new money into the banking system to lend further to the government. Demanding a higher spread on money that SBP, which is also the banking regulator, had lent cheaply, would have been a bit too much to digest for the SBP. So, these low ADR banks were left with two choices now, they could either continue to maintain low ADRs and as a result pay a much higher tax to the government. Or they could finally start lending to the private sector, improve their ADRs and avoid the extra tax. And lending they did. Well, sort of.

Banks start to lend. Or do they?

As mentioned earlier, it’s not like all commercial banks had a low ADR issue going into the year end. Some Pakistani banks do actually believe in lending, as opposed to prioritising investing in government bonds. Take Faysal Bank which already had an ADR of 67% at the end of Sep 2022, three months prior to the year end. In fact the overall industry ADR stood at 49%, only one percentage point below the 50% ADR required to avoid the extra tax.

This means the banking industry was, on average, already lending almost half of its deposits. It is only when one digs deeper into data of individual banks that one realises that four particular banks stand out in all of this: UBL, MCB Bank, Allied Bank and National Bank of Pakistan (NBP). All these banks have three things in common: 1) they are all big legacy banks, 2) all of them had low ADR at the end of Sep 2022. And 3) all of them suddenly started lending towards the end of 2022 and managed to increase their ADR beyond 50%. This meant that at year end, barring one small bank, there was not a single bank left that had to pay the additional ADR related tax.

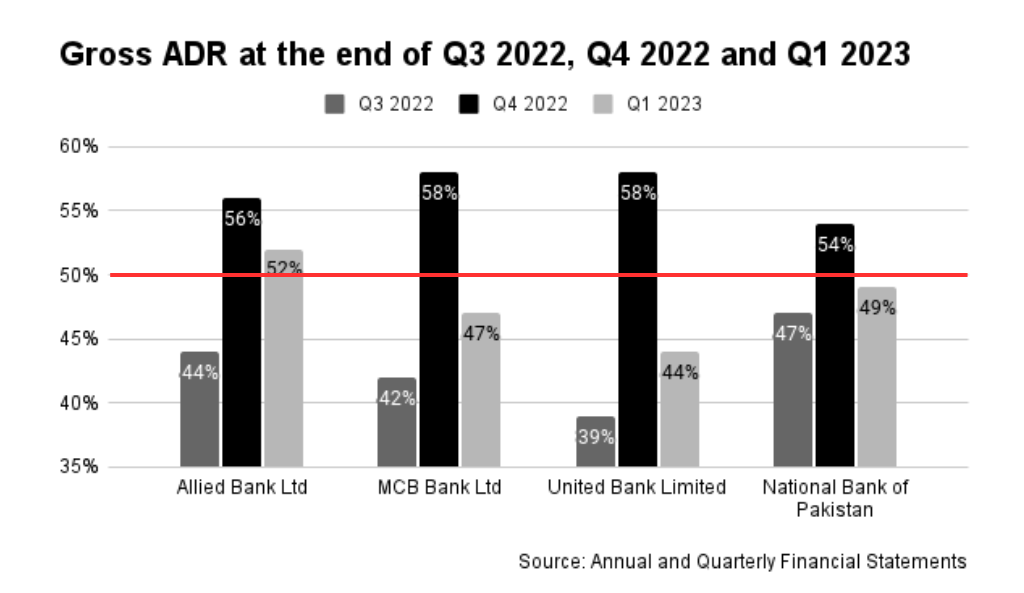

To understand the scale of this lending spurt, let’s start from the top. UBL had an ADR of only 39% at the end of Sep 2022, but when it disclosed its year end financials, the ratio had miraculously jumped to 58%; MCB had an ADR of 42%, which increased to 58% in the same three months; Allied Bank had an ADR of 44% which increased to 56% and NBP had an ADR of 47% which increased to 54%.

Not surprisingly, the ADR of all four banks dropped considerably soon after, so much so that the ADR of three out of the four banks is already back to being below the 50% threshold. This made the suspicion of possible year end window dressing even stronger.

But to whom and for what? (do not skip anything now)

Let’s get one thing out of the way first. It is an open secret that every year Pakistani banks indulge in a bit of window dressing to make their year end financials look better than they actually are. And it’s a pretty simple process. Imagine it is the last working week before the year ends and you have to make a big payment through a pay order for a house you recently bought. Two things can happen: either you will get a call from your branch manager requesting to delay the payment till 1st of January, or they may just ask their subordinate responsible for making the pay order to slow down the process. You know where they tell you “system down ho gaya hai”.

Similarly, on the advances side banks’ credit managers, call up their clients at year end and request them to borrow any underutilised lending limits, even if this is to be done for a few days. This makes the banks look slightly better in terms of their lending habits (better ADR), than they actually are.

So why do this story? Because the sheer scale, the reasoning for doing it, and the process through which it was done make this window dressing exercise way different from anything we have seen in the past.

So this is how they did it. We know that ADR is advances divided by deposits. Before coming to the advances (don’t worry, we tackle those in detail in a minute), let’s get the deposit component out of the way first.

Even though it is intuitive to assume that when banks were asked to improve their ADR, the government wanted the banks to lend more. But in theory banks could also increase their ADR if they could somehow reduce the denominator, i.e the deposits. They actually ended up doing both.

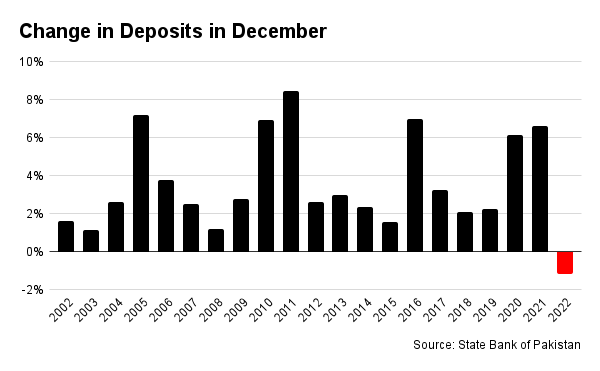

Hence for the first time in the last twenty one years (prior data is not available), in the last month of a financial year, banks opted to decrease their deposits, causing the number to drop by Rs 265 billion in Dec 2022. This break from the traditional pattern where banks would artificially hold onto deposits to meet performance goals and inflate their deposits in the month of December, only to release them in January was a first.

There was a complete lack of the usual year-end efforts to keep deposits up, no relationship managers (RMs) making phone calls and visits to clients to persuade them to not make any major withdrawals or to move some money from other bank accounts into theirs. None of that.

But this intentional reduction in the denominator part of the ratio is not enough to go above the crucial 50% ADR number. This is where the advances come in and where the real gimmickry is visible. As mentioned earlier, there was an unprecedented astronomical increase in advances in Dec 2022, Rs 820 billion worth. That it came in an economic climate where businesses are having a hard time keeping their heads above water makes the number all the more intriguing.

Let’s break down the Rs 820 billion figure a bit to understand who borrowed it and why.

Financial institutions other than commercial banks

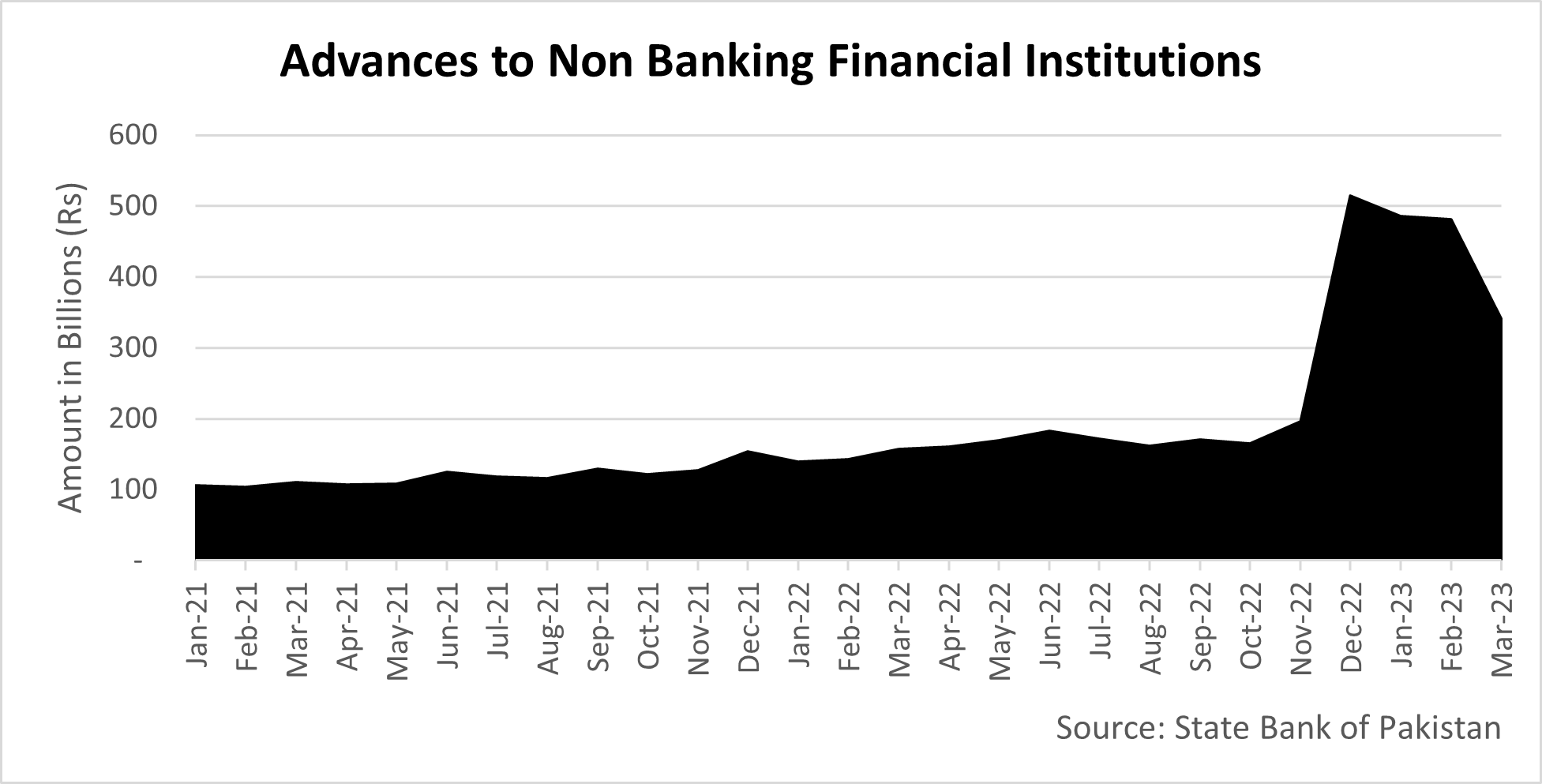

This is where a major chunk of the increase in advances was made, to be more precise an additional Rs 318 billion was lent to Non Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs) in the month of Dec 2022 only. This translates to an astounding 162% increase in advances to this sector, and what stood out was that never before had the combined advances to this sector crossed even Rs 200 billion, and here just the increase in a single month was much more than that. But who are these NBFIs and what did they do with money? You see, commercial banks are not the only businesses whose primary activity is dealing with money and other monetary assets. In fact we also have many other financial institutions that, barring few differences, work very similar to the commercial banks. Take the example of Microfinance banks. Like commercial banks they also take deposits, make advances and yes, invest in government bonds. Hence, the loophole to avoid the ADR tax was right there. Commercial banks could easily make loans to microfinance banks and ask the microfinance banks to invest those funds on behalf of the commercial banks in government securities. The commercial banks and the microfinance banks could then share the profits. This way the loans made to the microfinance bank would show up as lending to the private sector (advances) in the commercial bank’s financial statements and inturn increase the commercial bank’s ADR. And this way the microfinance bank’s ADR doesn’t get negatively affected either, because this transaction neither relates to the deposits, nor the advances figure of the microfinance bank. And even if it did, the ADR related taxation was only levied on commercial banks.

Editor’s note: In this story we have not explained the specifics of how these transactions are being structured between the banks, microfinance banks and in some cases the asset management companies of these commercial banks. However, if this interests you, you can read the fascinating piece titled: “Grow your company size by 3 to 6 times in just months. At least two Pakistani companies have done this & you can too. Here is how”, which is also attached at the end of this story.

Of these, the financials of U Microfinance Bank (UBank) stand out. Its borrowings increased from Rs 37 billion in 2021 to Rs 116 billion in 2022, a 3 times increase in just one year. And what did it do with this additional Rs 79 billion? You guessed it! It invested this, and then some in government bonds with a total Rs 91 billion increase in investments in 2022.

Of late, Microfinance banks in general have been struggling financially. So the fact that UBank was able to borrow Rs 40 billion from Allied Bank Limited, MCB and Askari Bank seems strange. Why have banks chosen to lend to UBank, especially given the wider struggles within the microfinance banking industry?

Kabeer Naqvi, CEO UBank, while speaking to Profit explains that since the regulator allows microfinance banks to make investments, they invest in government securities and will continue to do so and expand to become the first microfinance bank in Pakistan with an active treasury and for this have created strategic alliances with multiple banks and to create a win-win situation for both to facilitate this.

What Kabeer is essentially suggesting is that the practice of borrowing from commercial banks to invest in government bonds is normal, and they have been at it for a few years. He is right, UBank has been growing its investments and borrowings for quite a few years now. The fact that this year the increase, especially in absolute numbers, was much more leads us to believe that banks, at least some of them, were too keen to lend to UBank to avoid the ADR tax, but since there is no way we can know the intent of the lenders or the borrowers, unless they themselves confirm, we can leave it here for our readers to make their own conclusions.

But there is one player who unequivocally confirmed what we are suggesting.

Within the NBFI space, like microfinance banks, we also have a set of financial companies that are called Development Finance Institutes (DFI). These are owned jointly by the Government of Pakistan with another foreign government. One such DFI, disclosed to Profit that two to three banks approached them towards the end of 2022 and offered them a loan at extremely low rates. The DFI in question confirmed that the interest rate on these loans was even lower than the rate at which SBP lends to banks. This rate charged by the SBP, as also explained earlier in the story, is the cheapest possible loan in the financial industry. What did the DFI do with this cheap loan? it obviously bought government bonds and made a quick buck.

The DFI disclosed that these discounted loans were extended by two banks, UBL and Allied Bank, and since these loans were very short term in nature, these have already been paid back. This disclosure is a smoking gun! There is simply no possible explanation for UBL and Allied Bank to be making loans at a loss, (borrowing from the SBP and then lending to a DFI at a rate even lower than the rate being charged by SBP), other than that they were doing this to artificially improve their ADR, and avoid the extra taxes associated with a low ADR.

Both banks simply did the math: the tax saving from the ADR tax you avoid more than justifies the loss taken on the loan made to the DFI at a loss.

Both UBL and Allied Bank declined to respond to any of our queries that were sent to them over ten days back.

Editor’s note: Profit managed to get confirmation from one borrower, but the regulators, with access to detailed data, can ascertain the scale of this exercise and also find out which other banks were involved in it.

The rest of it

Apart from DFIs, private sector lending was another important avenue for commercial banks to manage their ADR problem. In fact total advances to the private sector increased by an impressive Rs 450 billion. This, as previously mentioned, was surprising considering the very high interest rate environment and the bad state of business and economy. However, to make a deeper analysis the availability of data in this respect is scarce. The little data that is available is sector wise making it difficult for us to ascertain which particular companies took a route similar to that of NBFIs to cater to the banks. That is how much of this additional lending to private sector businesses was further investment in government bonds by these companies. Just in case you didn’t know, any business or even an individual can invest in government bonds. It’s just that they have to go through their commercial banks who are the only ones allowed to participate in SBP conducted auctions of government bonds. That said, here too are some things that are just too blatant to ignore.

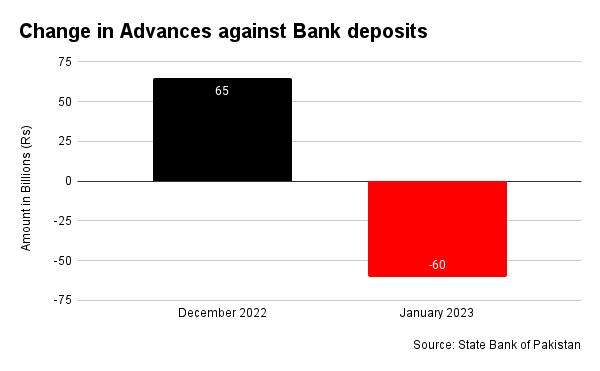

In December 2022 banks extended Rs 65 billion worth of new loans against bank deposits. This means businesses took out loans after giving their own deposits as securities against those loans. If they needed money why didn’t they simply use the money in their own bank accounts instead? This makes little sense at first. Why would any business with money in its bank account borrow against that same money and pay interest for a loan it doesn’t require? Absurd as it may sound, businesses sometimes do borrow against their own bank deposits for various reasons, which are not relevant to this story. But what is relevant is that this lending against bank deposits increased all of a sudden in December 2022 by 16%. That’s a big increase for one month. What makes it further suspicious is that the very next month the extra amount lent had dropped by approximately the same amount.

Directed by our many conversations with various corporate bankers, this year-end borrowing against banks deposits for a few days can be explained by some good old relationship management.

“Hey there SMEs. Do you want better rates from us next fiscal year? Do us this solid now and you got it!’ Hello Corporates. Look, we’ve known each other for a while, been through a lot together, and this is us calling in that favour,” the RMs would go.

And of course, there is the profit making opportunity that Pak Kuwait and UBank availed that these private sector companies could also have benefited from while also making their banks happy. That is, these private sector businesses could have also used these and other loans they took at a relatively low interest rate to make investments in government securities.

Playing the devil’s advocate: Making a case for banks

None of the banks contacted for this story responded to Profit’s queries. However, to understand the decisions being made by the C-level executives and board members at these banks, your correspondent spoke to a number of industry experts and gathered some background information to craft what a hypothetical reply in support of the banks’ actions would look like:

- The Pakistani banking industry is already highly taxed. In 2021, when the seeds for this current situation were sown, the corporate income tax on banks was a steep 35%. That is 6% higher than the 29% figure that is imposed on non banking-businesses. Afterwards the tax rate was further increased to 39%. And then there is also a super tax on banks.

- There is this general perception that banks are greedy. To that I would say, yeah so what? Banks are in the financial sector to make money and there are no two ways about that. So what is wrong with being greedy? If a bank ever gets exploitative that can be managed with regulation but greed is good because it helps the bottom line for our shareholders. If we are in it to make money, why would they choose to do the government favours at the cost of their own bottom lines?

- And then this is the most important part that no one will tell you on record. Yes, we do hop around the government’s drawn lines every now and then. It is called utilising a loophole and there is nothing strictly illegal about it. Generally speaking, the banking sector does use loopholes but usually sticks to the legal route. And in this particular case, forced lending can be bad for the banking system’s stability. The banks have to control who they hand it out to.

Read more: Pakistani banks don’t lend to the private sector. For good reason

ADR tax removed

It was clear that the tax was not working. Banks had found a work around. One thing was for sure. Some of the legacy banks would just not change. And as explained earlier there is a case to be made for this in the Pakistani context. So the government in Feb 2023 removed the ADR related taxation.

However under Miftah, the government did one more thing. It created competition for the banks by also allowing DFI’s to borrow from the SBP. Also within the commercial banks, NBP which is a government owned bank, has become the most active player in government bond auctions. Government bond holdings of all commercial banks increased by Rs 3.3 trillion in 2022, out of which 1.54 trillion was just attributed to NBP.

What now?

So here we stand. We started the story with a small development that took place back in 2021. The government of Pakistan came out swinging against commercial banks for not lending enough money to commercial clients. To make the banks change their ways, the government imposed a tax on banks with an ADR ratio less than 50%. However, the government was still reliant on commercial banks for a lot of their money and asked them to lend money by picking up government bonds.

That’s when the banks bit back. They demanded a much higher interest rate than the government was willing to pay. What followed was a Mexican standoff that eventually ended with the banks doing some clever book-keeping to alter their numbers and the tax being removed. So what was the point of this entire episode?

There are a few interpretations to this.

The first is that the government wanted to punish the banks and managed to impose a tax on banks. And while the tax has been removed, the government has now found an alternate route to borrow money through DFIs instead of commercial banks. At the same time, while the ADR tax has finished, the government has since imposed a super tax that cannot be manipulated.

Then there is the other interpretation. That it was not so much the government putting up a fight and the banks reacting as it was the banks stepping back from doing business with the government. You see, buying government bonds is considered a safe investment since the government is not really supposed to go broke. However, over the past few months along with talk of sovereign default there has also been discussion that Pakistan might be headed towards domestic debt restructuring. Essentially, if the government is unable to pay back the banks the banks will have to move the repayments forward and take a loss on their books. As a result, the banks decided to ask for a higher interest rate on bonds since the government was now a risky investment. Take Allied Bank for example. One of the bigger banks in Pakistan, they actually stepped away from their primary dealer status to avoid having to participate in the auction for government bonds.

As of now, everything is back to normal. Deposits are being channelled to the government, if not directly then indirectly. SBP is lending to the government and mostly through entities with a large government stake. Government has imposed additional taxes on bank’s incomes, but without a link to any other metric that can be manipulated. Seems everyone has learnt their lessons and to some extent everyone is back to being happy again.

Disclaimer: Some concepts and definitions have been simplified for purposes of brevity and clarity.

Amazing Article! I appreciate you providing this useful content, and I look forward to the latest one.

An amazing investigative article and exactly the sort of content Profit should should come up with. @2paisay – great job on this as well as your tweets.

Superficial analysis, you need to dig deeper to understand how Banks function, they have costs and return for shareholder when taking risks.

Superb content, thanks for explaining in a way that non-finance person like myself could understand.

Keep up the good work

Agreeing with Meeru. Limited scope on this article. You did not blame the govt. for distorting the market. The unintended outcome of legal but “sham lending” was because the government interfered with the market. You want the private sector to borrow more please have the public sector borrow less so they don’t “ Crowd out” the private sector. These are well defined economic concepts. Instead the government chooses to keep white elephants like PIA, Steel Mills, ghost schools, ghost health facilities, etc and spend on them by borrowing. Even the size of the government is too large. The government also distorts its own tax base by making certain entities tax free like AWT.

Unless the govt reforms this will continue to happen.

Very detailed article on how market behaves when government deliberately create distortions. Banks are charging more risk premium as GOP has become economically vulnerable. Instead of fighting with banks, government should decrease its discretionary expenditure and opt for fiscal discipline. This is the only way we can eliminate crowding-out effect and enhance the space for private sector.