In 2022 India exported over 22 million tonnes of rice to the entire world. As the single largest exporter of white rice in the world, India control’s a massive 40% of the global market for rice providing different kinds of rice that many other countries in the world are heavily dependent on for their caloric intake.

And this year the Indian government has put a ban on the export of all kinds of rice except the aromatic and high-end Basmati variety. The ban comes in response to soaring rice prices in India and a general food inflation crisis that has been brewing in the country.

As a result, the international rice market suddenly finds itself short on more than 10 million tonnes of rice. With a global food crisis already about to reach crescendo because of the Russia-Ukraine war, rice importing countries and international organisations are suddenly faced with a concerning question: how will this massive shortfall of rice be met?

Already the news of India’s rice ban has resulted in supermarkets facing panic buying all the way in the United States and other countries that rely on Indian rice. Some other countries that are also exporters may also follow suit with a ban to protect their own domestic markets. So who will take the opportunity?

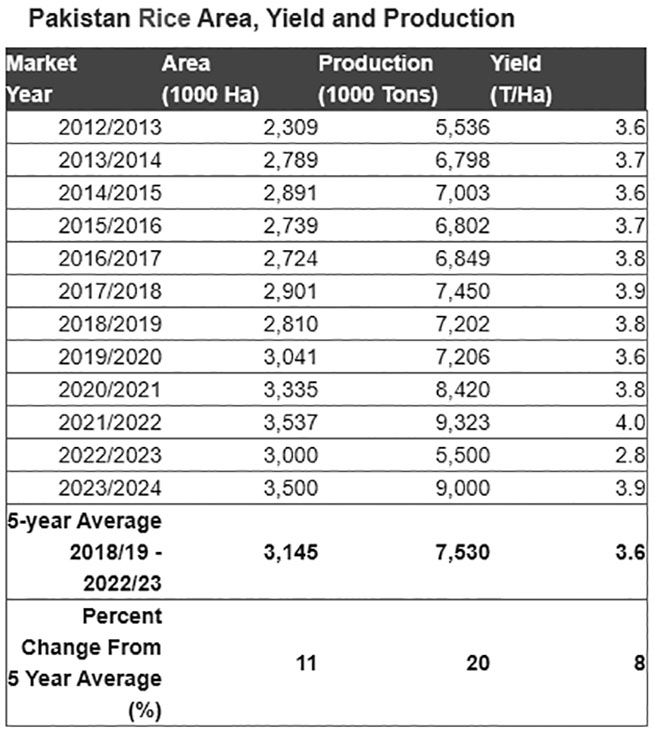

Well, possibly Pakistan. While India might be the largest exporter of rice with Thailand at a distant second place, Pakistan is number four on the list of largest rice exporting countries in the list with Vietnam in the middle at number three. In 2022, Pakistan’s total rice production was just over 5.5 million tonnes and the total export was around 3.5 million tonnes. This year, with a good harvest, Pakistan could have a much bigger market to export its rice to.

But why is India not exporting rice this year, and more importantly, how can Pakistan best utilise this situation?

India’s export ban

The announcement came last month, when on the 20th of July the Indian government quietly made the announcement that it would not be exporting rice other than the Basmati variety. The Indians claimed they were doing this to tame surging domestic food prices and “ensure adequate domestic availability at reasonable prices.”

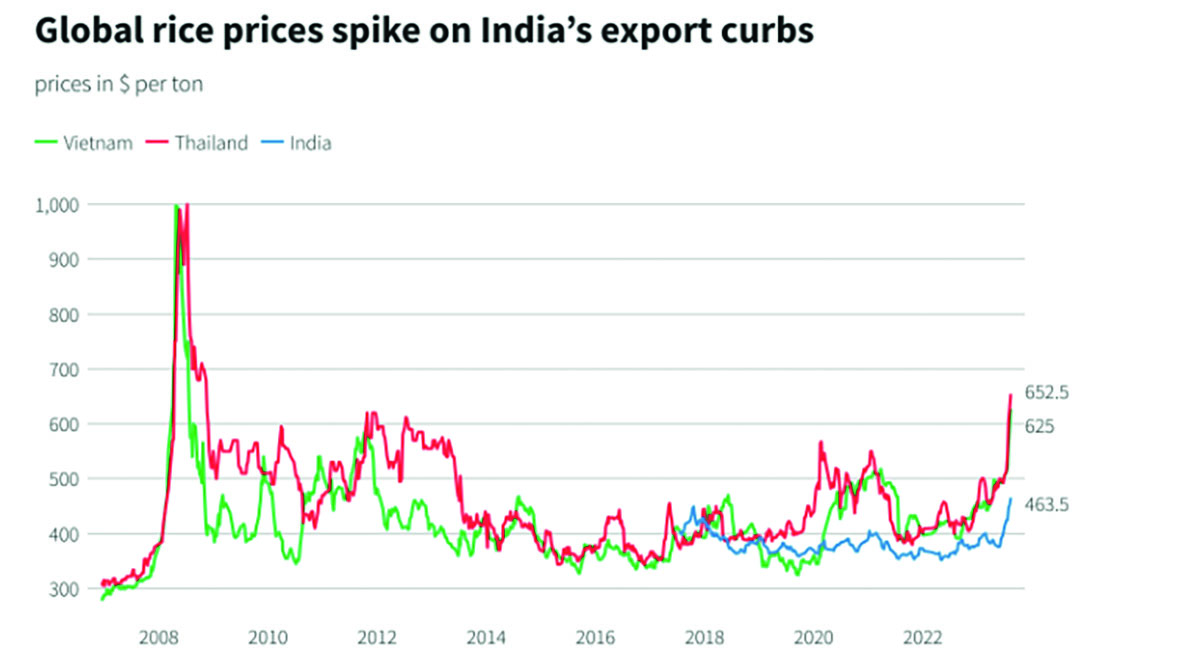

But the results are not pretty. The impact on prices of the world’s most consumed staple has been swift, hitting 15-year highs. Limited supplies risk a further spike in the price of rice, and global food inflation, hitting impoverished consumers in Asia and Africa, analysts and traders said. Food importers are already grappling with tight supplies caused by erratic weather and disruptions in Black Sea shipments.

Global rice prices, as tracked by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) All Rice Price Index, rose 2.8% in July, or 20% year-on-year, to their highest level since September 2011. Indica rice, the primary crop grown in India and other parts of South Asia, accounts for roughly 70% of the global rice trade.

The FAO warned that the price rise “raises substantial food security concerns for a large swath of the world population, especially those that are most poor and who dedicate a larger share of their incomes to purchase food.”

The broader FAO Food Price Index, which tracks a basket of food commodities including rice, cereals, dairy, and meat products, rose a more modest 1.3% from June and fell 11.8% from year-ago levels.

“Thailand, Vietnam, and other exporting countries are poised to step up their game, all in a bid to bridge the gap stemming from India’s shortfall,” said Nitin Gupta, senior vice president of Olam Agri India, was quoted as saying by Reuters. Olam Agri is one of the largest rice exporting companies in the world.

As a result, rice exporters will be unable to increase exports by more than 3 million metric tonnes a year as they try to fulfil local demand amid limited surplus. At the same time the rice market in India is facing a serious jolt. According to an Indian research institution, ice planting in India could fall by as much as 5%.

According to a statement issued by a leading farmers’ group close to the ruling BJP, New Delhi’s decision to ban non-basmati white rice exports will cut farm income and encourage growers to switch to other crops.

The decision has sent waves even within farming groups sympathetic to the government. “The rice export ban was announced right in the middle of the current planting season, and that’s why the decision has sent a wrong signal to farmers,” Mohini Mohan Mishra, general secretary of the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS), said in a statement.

Despite this, it seems that soaring inflation left the government with no option but to enact the export ban. Earlier, the government had tried placing a 20% duty on exports as a deterrent to rice growers and exporters so that they would focus on the local market and help bring food prices down in the lead up to both federal and state elections next year.

Global rice market dynamics

While India’s decision is causing plenty of domestic angst, it is also a bright opportunity for other rice exporters to take charge. There are thousands of varieties of rice that are grown and consumed, but four main groups are traded globally. The slender long grain Indica rice comprises the bulk of the global trade, while the rest is made up of fragrant or aromatic rice like basmati; the short-grained Japonica, used for sushi and risottos; and glutinous or sticky rice, used for sweets.

China, the Philippines, and Nigeria are primary purchasers of rice. Meanwhile, nations such as Indonesia and Bangladesh, often termed “swing buyers”, increase their imports when facing domestic supply deficits. Rice consumption is not only high in Africa but also on the rise. For countries like Cuba and Panama, rice is a principal energy source. In the previous year, India shipped 22 million tonnes of rice to over 140 nations. Out of this, the more affordable Indica white rice accounted for six million tonnes. For context, the global rice trade is estimated at 56 million tonnes.

Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan, the world’s second, third and fourth biggest exporters, respectively, have said they are keen to boost sales since demand for their crops has been rising after India’s ban. According to initial reports there is a major role for Pakistan to play in this crisis. But will the Pakistani government bite? Pakistan, recovering from last year’s devastating floods, could export 4.5 million to 5.0 million tonnes according to an official with the Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan (REAP). But already REAP is worried that since food inflation is already pretty high in Pakistan, the government might not be so keen on exporting rice since it will become expensive on the global market.

Fighting our own demons

The situation is tricky for Pakistan. On the one hand there is an opportunity to export rice and earn foreign exchange – something for which rice growers will be very keen. On the other hand, there is the very real possibility that if a vast majority of our rice gets exported, prices in the domestic market will rise sharply. Pakistan is already reeling from inflation.

A day after the country’s national assembly was dissolved, the ministry of finance said that Pakistan was facing five major and persistent economic challenges, resulting in rising poverty and social vulnerabilities. Rising inflation, particularly food inflation –– the highest in the history of Pakistan –– increase in administered prices of petroleum products, electricity, and gas and continuous depreciation of the country’s currency. All this will have a negative impact on household consumption leading to greater poverty, particularly in rural areas, the ministry highlighted.

It is a question that other major rice exporters are also grappling with. Both Thailand and Vietnam emphasised that they will ensure their domestic consumers are not hurt by rising exports. “It’s unacceptable for a rice-exporting country to face tight supplies and high domestic prices,” Vietnam Minister of Industry and Trade Nguyen Hong Dien said last week.

It must be remembered here that Pakistan has the opportunity to take some of the Indian market away not in the long-term but just this year in particular. India is facing high food inflation for the same reason that the rest of the world is: the Russia-Ukraine war. Next year, if India is not facing similar food inflation, they will be back to take their place as the biggest rice exporter in the world. The question that faces policy makers is whether or not a one time export boost is worth the immediate pain that short term inflation will cause the public. Since it is caretakers that will be taking these decisions, there is no question of electability here but a simple matter of cost-benefit analysis that the finance ministry will have to do.

India’s inflation rose to 4.8% in June on the back of soaring food prices — still within the central bank’s inflation target of between 2% and 6%. However, inflation “threatens to come in at 6.5% in July,” HSBC estimated in a report dated July 24. HSBC economists cautioned that extreme weather events could further put a strain on crop output.

That is exactly what happened. Inflation peaked at 6.40% in July, breaching the Indian central bank’s upper limit of 6%.

Wheat prices jumped after Russia withdrew from the Black Sea grain deal. Under the agreement, Moscow agreed to allow Ukraine to continue to export grain in a bid to prevent a global food crisis following the war on Ukraine. But the Kremlin pulled out of the deal in July, claiming promises made to Russia under the deal were not met.

Could Pakistan pull it off?

Pakistan cannot come near fulfilling the world’s rice demand. The total shortfall from India’s decision to ban the export of varieties other than Basmati (which is a big seller) has caused a 10 million tonne shortage. Pakistan’s overall production was only 5.5 million tonnes last year. But that was a bad year because of lasting damage and water logging from the 2021 floods. This year the country is expecting a harvest of over 9 million tonnes which could mean exports of 4.5 million to 5 million tonnes if half the total production is exported.

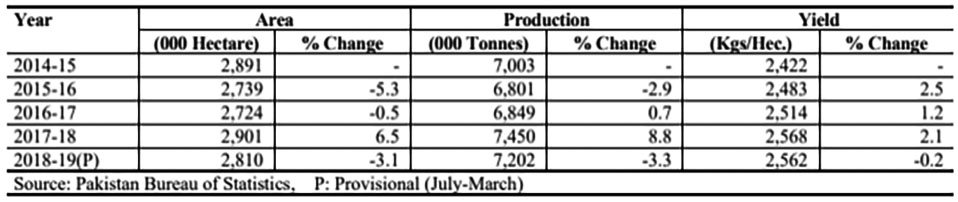

The rice sector in Pakistan is extremely important in terms of export earnings, domestic employment, rural development, and poverty reduction. Rice is an important food as well as cash crop in Pakistan. It accounts for 3.0 percent of the value added in agriculture and 0.6 percent of GDP. After wheat, it is the second main staple food crop. During 2018-19, rice crop area decreased by 3.1 percent (to 2,810 thousand hectares compared to 2,901 thousand hectares the previous year).

The problem is that for any long-term change Pakistan needs to make significant amendments to its agricultural systems. This year could have been a great opportunity to find new markets for the export of rice but instead Pakistan will only be a stop-gap solution at best because it is uncompetitive.

Despite significant improvement in yield during the 2000s, Pakistan has lost the competitive edge in basmati as indicated by its plummeting shares in total basmati export from 46% in 2006 to less than 10% in 2017, which was conveniently picked up by its competitor India. Pakistani basmati exports also declined by 45% in absolute terms during the period. This declining competitiveness is due to a number of factors that favoured India than Pakistan during the period, including stronger technological innovations which gave higher productivity growth in basmati that have more elongated kernel size without aroma, and lower production costs due to high input subsidies.

According to a 2020 study of the planning commission, for Pakistani rice to become competitive on the international market it needs six interventions: i) gradual shifting to mechanical rice transplanting which is needed for increasing plant population and long awaited productivity enhancement issue of the area; ii) diffusion and adoption of high yielding varieties in the area which is required to replace the varieties like basmati-386, Supra, Supri, etc.; iii) introducing improved crop management practices as large gap between average and progressive farmers’ yield and associated variations in crop management practices can be noticed across farms; iv) shifting to rice combine harvesters which are essentially needed to control harvest and post-harvest losses in milling and address the problem of burning of rice straw; v) introduction of paddy drying at farm level in order to improve the quality of paddy and its by-products; vi) introduction of rice bran oil to diversify rice value chain.

This year the government will have to make a difficult call on the issue of rice exports. Increasing exports might not be worth the headache of increased inflation in an already brutal inflationary cycle, especially if the same cannot be repeated next year, but there is the foreign exchange earning consideration as well.

Good idea! Exports will help Pakistan manage currency crises.

This is a really helpful post. Thank you very much for sharing it for me and everyone to know.

India did not put this export ban primarly because of low yields. India did this to get better prices as and when the export starts. Kindly try to understand that paddy cultivation requires hell lot of water and majority of the countries around the world lack this resource. So before starting to exprot exporting rice, what India wants is more price for the rice export as then it can make good money by exporting lesser quantity and also the price of rice will remain under check in India with enough avalaibilty. This is called Baniye ka demag 🙂